Mobilities

David Sadoway

David Sadoway is a faculty member in Geography and the Environment as well as Policy Studies at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. As an urban planner and an environmental manager, he has worked with the United Nations, various levels of government, non-profits, and urban planning consultants. David previously lived and studied in various Asian cities over a 15-year period.

Grounding Perspectives on Mobilities: Theory meets practice in an artist’s eyes

The COVID pandemic provides important insights on (im)mobilities. Quarantine, lock-down, travel bans, and physical distancing measures have resulted in noticeable changes in both global and local (g/local) flows of people, capital, goods, services, information, and ideas. In several geography classes during the pandemic, I asked students to make “Before/During COVID [BC-DC] Mental Maps” to discuss changes in their movement patterns, such as to/from home, school, work, or recreation. For example, during the early months of the ‘lock-downs’, many of these BC-DC maps illustrated tightly constrained movements and less or non-use of various mobility modes (i.e., jogging, transit, car, etc.), as home confinement and school or workplace restrictions took effect. Later, as various restrictions were amended, mobilities across cityscapes and beyond morphed.

Mapping travel (im)mobilities across time and urban space can serve as a useful approach for analyzing broader patterns in movement practices, under distinct circumstances such as a pandemic. Indeed, the very definition of a pandemic (i.e., a global-scale disease outbreak) underscores not only dramatic shifts in movement practices across world systems, but also in many other ways: changes in urban-rural migrations; altered (home)workplace operations; amended shipping or logistics schedules or flows; transportation choices; variations in information communication technology usage; fluctuations in tourism flows and behaviours; and so forth.

The pre- or in situ pandemic mobilities of relatively materially affluent tourists, can be compared with many residents of the Global South, particularly non-elites, many of whom have not had access to vaccines, let alone mobility affordances. Mobilities can therefore highlight the glaring global disparities and inequalities within and between societies. Besides demonstrating changes in human mobilities during the pandemic, COVID also illustrates how vaccine technologies and public health ideas were mobilized around the globe. Ideas, plans, designs, policies, programs, and agendas can also be mobilized (in this case amongst privileged societies first).

Who has agency in questions related to mobilities? The concept of geographic scale and socio-technical modes of mobility becomes crucial when discussing how and why people can move or mobilize. Race, class, caste, age, and ability critically shape who and under what conditions individuals and communities have access to mobility options or infrastructures. In materially wealthy states and increasingly much of the Global South, personal mobility choices often revolve around automobility—the use of private/personal vehicles for movement. This in turn has important ramifications for urban form, functions, and placemaking. The global rise of automobility also shapes myriad aspects of the quality of urban life and has spawned entire (sub)cultures (car culture, off roaders, racers, commuters), economics (direct and indirect manufacturing jobs), automobile dependent urban forms (suburban sprawl) and places (parking lots/garages), and increasingly oil- or gas-polluted carbonscapes.

Mobilities scholars and urban designers or planners are increasingly interested in designing cities to be more transit friendly, accessible, walkable, and liveable—beyond simply becoming community spaces that are dependent upon or consumed by car culture and automotive infrastructures. As before the pandemic, however, the issues of a growing auto-dependency (including limited transit choices for many working class suburbanites) underscore the need for alternatives to car culture.

The examples above serve to illustrate that mobilities relate to technological and modal choices (e.g., air travel vs. bicycle), but also the geographic scale of movements and infrastructures, whether within the home, neighbourhood, community, urban region, or beyond and between. A lack of access to mass transit or the ill-conceived placement of a bridge or road can result in socio-economic or environmental injustices in the present and far into the future. Mobilities research can therefore provide critical insights into socio-economic flows, traffic, designs, or practices over time and across geographic space, as well as a path for understanding power asymmetries and injustices inherent in these systems.

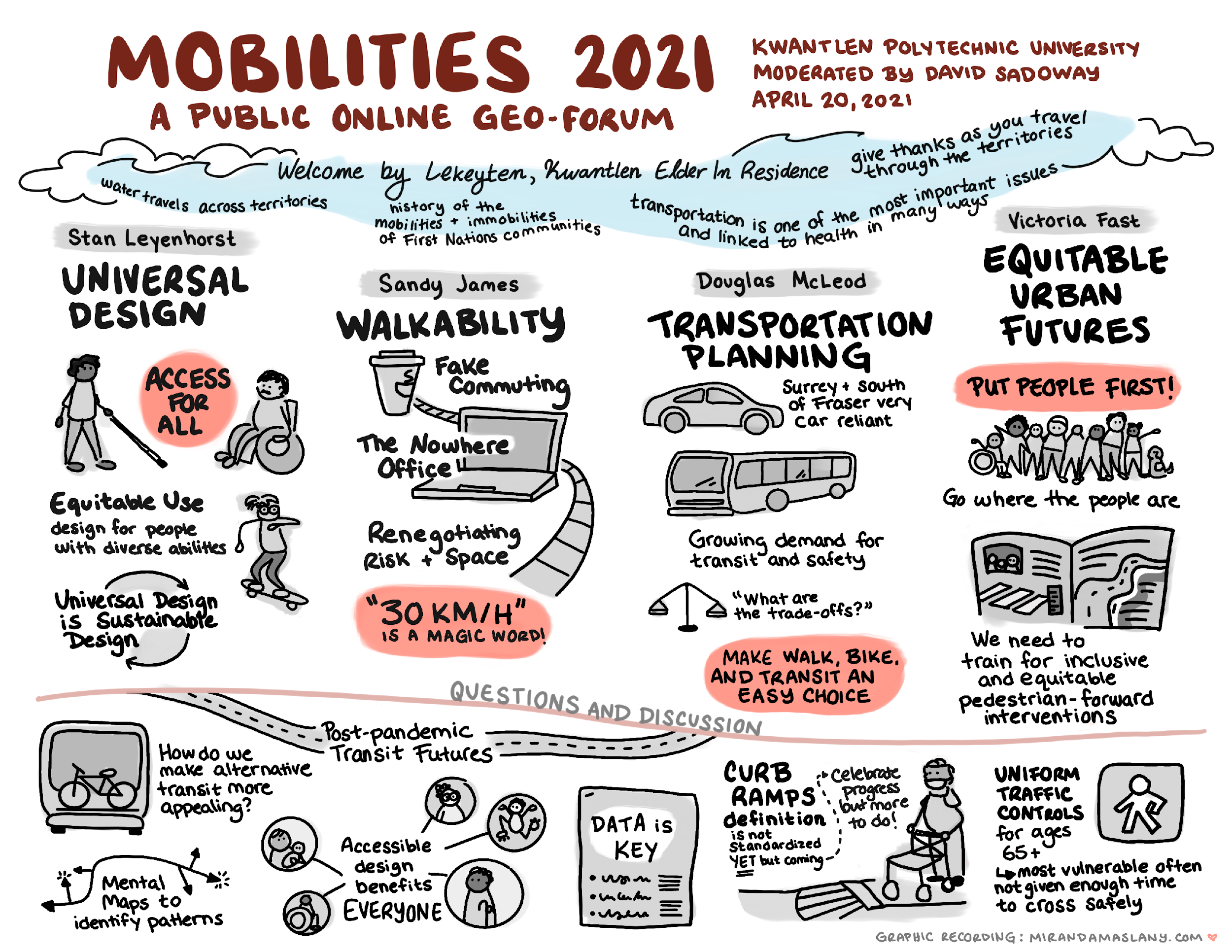

A helpful illustration of distinct debates about mobilities at the local level comes from an artist’s graphic recording of an event held online in April 2021 (see Figure 1). This event, while focused on mobility questions that were local in nature, is illustrative of several distinct perspectives. The online Geo-Forum included presentations about First Nations perspectives on mobilities, universal design (for variously abled residents), walkability, city-level transportation planning, and equitable urban futures for all. The online presentations and dialogue served to illustrate how questions about mobilities (dis)connect present mobility patterns from longstanding historical uses and practices; and shape the health of the people and places in our communities. Speakers at the event also highlighted that, while details about mobility can potentially get bogged down in technicalities, it remains crucial to widely involve diverse publics when considering mobility options, not just simply auto drivers.

The artist’s visual synopsis of the event synthesizes and summarizes key details presented from the various speakers. For example, delightful urban spaces are often ‘car free’, or speed-limit restricted (e.g., below 30 kph), and placemaking should consider car-minimized spaces to enable people of all ages and abilities to access diverse community services. Envisioning liveable and just communities and societies must therefore involve tackling key questions about mobilities, ideally working with the distinctive local knowledge base of the diverse communities in our midst.

Discussion Questions

- What are some of the main modes of mobility that you and your peers typically use in any given week? What are some of the socio-economic and environmental consequences or challenges in making these choices? How could these consequences or challenges be addressed in your view?

- Drawing from discussion about the preceding question, what do you feel are some of the linkages between the climate emergency and mobility choices in our daily lives? To what extent is mobility a personal choice, and to what extent is it shaped by public choices and policies? What role do you feel collective choices should take in shaping mobilities, especially given that public roads are paid for by and available to all?

- Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? “High-tech solutions will eventually resolve mobility challenges and socio-economic asymmetries in the long run.” What might the role of low- or appropriate-tech mobility choices play in resolving mobility challenges (e.g., walking, biking, etc.)?

Exercises

BC-DC Mobilities Mental Maps. Working individually or in a small group, draw Before/During COVID mental maps of your mobilities. Share and compare with the rest of your class to examine commonalities and differences.

Mobilities of the Future. Envision your community 20 to 30 years from now. Devise several ‘mobilities visions for the future’ (i.e., future scenarios/future visions that centre on mobility choices and that improve socio-economic and environmental circumstances for diverse community members. For example, consider scenarios or visions that are linked to the five perspectives noted above (Indigenous, universal design, walkability, transportation options, equitability).

SEEing Mobilities. Sketch out how mobility could be improved in your community, not just from an efficiency perspective, but also from an integrated approach that links together social needs (e.g., housing, recreation), economic needs (e.g., access to food, shops, work), and environmental concerns (e.g., access to green space, reduced greenhouse gas emissions). How could mobility be planned better to integrate various needs, not just efficient movement, across or in your community?

Additional Resources

Antone, L. (2021). Welcome by Lekeyten, Kwantlen First Nation Elder-In-Residence (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Badami, M. & Tiwari, G. & Mohan, D. (2009). Access and mobility for the urban poor in India: Bridging the gap between policy and needs. Working Papers id:2310, eSocialSciences.

Fast, V. (2021). Equitable urban futures (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Foletta, N., & Henderson, J. (2016). Low car(bon) communities: inspiring car-free and car-lite urban futures. London: Routledge, DOI: 10.4324/9781315739625

Furness, Z. (2007). Critical Mass, Urban Space and Vélomobility, Mobilities, 2(2), 299–319, DOI: 10.1080/17450100701381607

Gopakumar, G. (2020). Installing Automobility: Emerging Politics of Mobility and Streets in Indian Cities. Open Access Edition, MIT Press. DOI: 10.7551/mitpress/12399.001.0001

Grengs, J. (2002). Community-Based Planning as a Source of Political Change: The Transit Equity Movement of Los Angeles’ Bus Riders Union, Journal of the American Planning Association, 68(2), 165–178, DOI: 10.1080/01944360208976263

James, S. (2021). Walkability (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Kaufmann,V., Dubois, Y. & Ravalet, E. (2018). Measuring and typifying mobility using motility, Applied Mobilities, 3(2), 198–213, DOI: 10.1080/23800127.2017.1364540

Leyenhorst, S. (2021). Universal design (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

McCann, E. & Ward, K. (2011). Mobile urbanism: cities and policymaking in the global age, Eugene McCann and Kevin Ward, editors. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McLeod, D. (2021). Transportation Planning (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Newman P., Beatley T., Boyer H. (2017). Create Sustainable Mobility Systems. In: Resilient Cities. Washington, DC: Island Press, DOI: 10.5822/978-1-61091-686-8_3

Sadoway, D. (2021). Introduction (presentation). MOBILITIES 2021 Geo-forum online. Department of Geography and the Environment. Faculty of Arts. Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Sadoway, D. & Shekhar, S. (2014). (Re)prioritizing citizens in smart cities governance: Examples of smart citizenship from urban India, The Journal of Community Informatics 10(3), DOI: 10.15353/joci.v10i3.3447

Sheller, M. (2021). Commoning mobilities: mobility justice, public space, and just transitions. In Public Space (16 June). Available at: https://www.publicspace.org/multimedia/-/post/commoning-mobilities-mobility-justice-public-space-and-just-transitions

Sheller, M. & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A, 38, 207–226.

Tiwari, R. & Rapur, S. (2019). Walkable streets “FOR the PEOPLE” “BY the PEOPLE”, Applied Mobilities, 4:1, 87–105, DOI: 10.1080/23800127.2017.1397418

Urry, J. (2004). The ‘system’ of automobility. Theory, Culture & Society 21(4/5), 25–39.