Providing Feedback

Why Feedback?

Feedback provides information to the student about how well they are progressing towards a goal or whether they have met an outcome. The key is focusing on areas of improvement in a constructive, not destructive, manner.

Types of Feedback

Constructive feedback offers corrective, or instructional, recommendations to improve performance. In some cases it may be substantial, and more minor in others. All feedback should always contain something for the student to strive towards.

Destructive feedback is non-progressive and generally elicits negative reactions or perceptions of worth.

Good feedback:

- Helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards)

- Facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning

- Delivers high quality information to students about their learning

- Encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning

- Encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem

- Provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance

- Provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape teaching.

(Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006)

Delivering Effective Feedback

There are several keys to delivering effective feedback.

Use the arrows to navigate between slides.

In an online environment, feedback can be provided through written annotation directly on work submitted, video recording using a tool such as Flipgrid or Loom, or using verbal feedback through audio software embedded within, or outside of, your LMS, such as Dragon Naturally Speaking or Loom.

When providing written feedback, think about the “sandwich method”

Try to provide a minimum of one sentence for each ‘layer’ and aim to start or end with a positive comment that allows the student to feel good about their learning, knowledge and/or understanding, or acknowledges their effort.

When providing feedback on authentic assessments, leverage professional expectations to demonstrate the link between what they are doing, how they completed it and to what degree/level, and what they would be expected to complete relative to professional roles and responsibilities. Where possible, it is best to also make connections to the use of professional resources and websites, and how those resources could have been best leveraged for the assessment.

Encouraging Reflective Self-Assessment and Feedback

Encouraging students to self-assess their work using a guided structure, prior to submission, offers them the opportunity to identify gaps, expand ideas, correct citation errors, incorporate formative feedback, and compare their submission to the assessment requirements as specified in the rubric, checklist and/or instructions.

This assessment should be framed around 3 distinct questions:

- Where Am I Going?

- Where Am I Now?

- Where To Next?

Adapted from (CSAA West Ed, 2021)

Providing students with a graphic organizer that directs them to critically review their work, or asking them to assess their work against the assessment rubric and having them submit that with their work, will encourage purposeful reflection on their attention to instructions, position relative to the target, and degree of effort put forth in completing the task.

Peer Review

Peer review can be used to provide formative feedback on the building blocks of a larger assessment, to communicate performance and engagement in group work, or to facilitate course evaluation for lower stakes assessments. Ideally, peer review for any assessment would be completed anonymously, and by more than one reviewer, to obtain the most objective and valuable perspective and recommendations.

Providing students the opportunity to have their assessment reviewed by peers prior to final submission offers a number of advantages for both the student and the assessor(s).

Use the arrows to navigate between slides.

Peer review and feedback can be quite successful and a valuable learning experience; however, setting students up for success in peer review activities through a solid foundation will be key.

Select a topic below, marked with an arrowhead, to reveal more information.

Establish expectations around conduct.

This should include using appropriate language and treating assessments with respect and confidentiality. Remind students that they are reviewing the hard work of one of their classmates, and that work should not be shared or discussed with other peers.

Collect assessments and remove identifiers before distributing for peer review.

This will encourage most fulsome, honest, and objective feedback, and increase the level of comfort for all engaging in the process. You may wish to develop a coding system for the submissions and the reviewer to facilitate your tracking of progress and completion, and more easily gather and return the submitted work and feedback.

Develop clear directions and a rubric or set of guidelines with criteria to guide the peer review process.

Include criteria to guide the peer review process. What should they focus on? How do they present their feedback? Involving the students in determining criteria will nurture ownership, investment, and accountability in the process and outcome.

Model good feedback practices.

Teach students how to deliver constructive feedback and provide exemplars for them to refer back to. It can be helpful to provide feedback on their feedback for the first couple of times they engage in peer review to help them identify areas they can revise and improve upon for the next time.

Start small.

Begin with a small assignment or a single component of a large assessment. This will allow students the opportunity to develop and hone their assessment skill set without feeling overwhelmed.

Single-point rubric

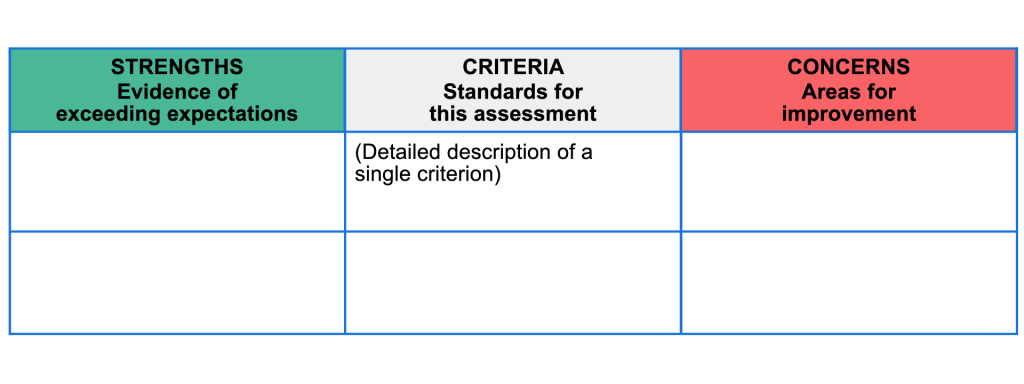

Rubrics, checklists, and rating scales can all be used for peer review as long as the criteria outlined are clear and specific so they are simple for the students to follow. Reviewers can use the actual grading rubric or checklist for the assessment, as provided by the instructor, or one can be created that is specific to the peer review process. This may be a multiple performance level rubric (as illustrated in the prior section on rubrics) or can be a single point rubric that simply asks for strengths and concerns. Cambrian College demonstrates the characteristics of a single point rubric:

The “Criteria” or standards for assessment are in the middle column. Each row contains a detailed description of a single criterion. To the left is a column for “Strengths” or evidence of exceeding expectations. To the right is a column for “Concerns” or areas for improvement.

Explore these sample templates for a single point rubric. Sample 1 and Sample 2

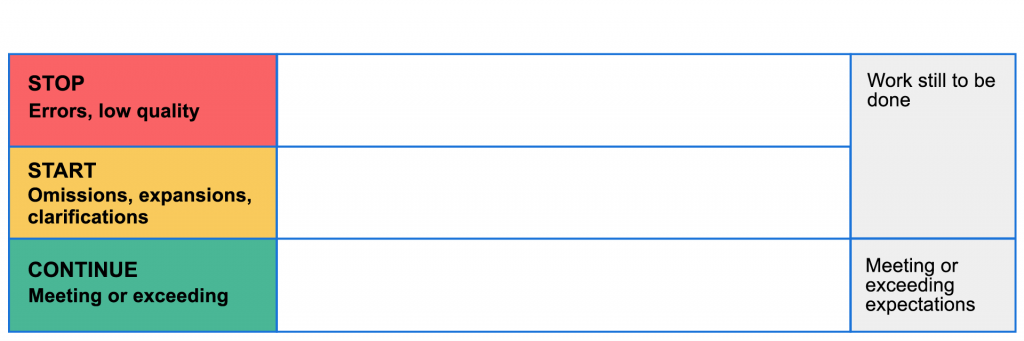

Stop-start-continue

A stop-start-continue could also be used, but is less focused on specific criteria or components of the assessment, and is, rather, a reflection of the assessment as a whole:

In this table, work still to be done is listed under “Stop” (errors or low quality) and “Start” (omissions, expansions, or clarifications). Work that meets or exceeds expectations is listed under “Continue” (meeting or exceeding).

Introducing peer review into specific assignments grants students the opportunity to view, and have their work viewed, through a new lens, offering a fresh perspective. Student and reviewer anonymity and a guided process are the cornerstones to building a successful peer review component into assessments.

Check Your Understanding

Activity

Identify an assessment in your course, or one that you are developing, and create a peer feedback tool such as a rubric (single or multiple point), checklist or stop-start-continue, and generate an exemplar that could be shared with peer reviewers. Share this tool, along with the associated assignment, with a colleague. Does your tool touch all of the important points on the assessment to facilitate improvement in student performance? Does the exemplar clearly demonstrate best practice with providing feedback?