29 Introduction to Diversity

Communication and Diversity in Canadian Workplaces

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter | module, you should be able to

- describe diversity within the context of a modern workplace,

- explain how language use influences communication in a diverse workplace,

- explain characteristics related to manifestations of diversity, and

- describe how diversity in the workplace can create challenges for effective interpersonal communication.

Are you familiar with the term diversity? Perhaps you have encountered it at your school or heard about it in the media. A diverse group is one that consists of people with different backgrounds, experiences, cultures, and traits. Canadian workplaces are becoming more diverse as organizations realize what a diverse workforce can bring, from innovation and creativity to employee happiness and retention.

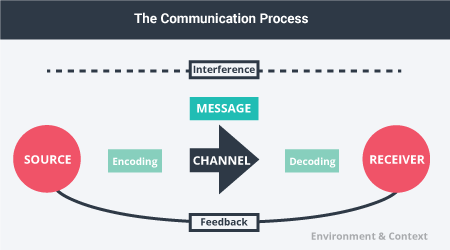

In this chapter we will explore some of the key types of diversity that you will likely encounter in your professional life. We begin with diversity essentials, reviewing the communications process with emphasis on encoding and decoding as the spots where communication problems can occur among people with different reference points. You’ll then learn about why diversity matters in Canada and get a glimpse into our changing demographics along with concepts and definitions useful to demystifying diversity as well as inclusion.

There are more types of human diversity than we can possibly list, but we shine a spotlight on religion and culture, linguistic diversity, gender, sexual orientation, generation and age, socioeconomic, and ability in this chapter.

With the benefits that a diverse workforce brings come communication challenges like similarity-attraction phenomenon and fault lines, which we examine near the end of the chapter.

Working with people who are different from you can be complex. When you navigate this environment, you will learn new terminology. You will also experience behaviours, approaches, misunderstandings, and sources conflict that you may not have encountered before. By learning about the intricacies of interpersonal communication in a diverse workforce now, you will be prepared to develop mutually beneficial relationships in your future that can include anybody.

Diversity Communication Essentials

When we communicate interpersonally with someone who is similar to us in terms of thought patterns, language, gender, or peer group, for example, we encode a message using a given channel, and the receiver decodes the message in the way that we expect that they would. For example, you’re on the soccer field with possession of the ball, and you hear your teammate who is behind you clap three times. You know this means your teammate is open. You turn and give a quick pass, and your teammate makes a goal. This is an example of good, effective communication. But what if you interpreted your teammate’s clapping to mean that you should not pass the ball? You would have decoded this message in a way the sender had not intended, and you would have taken a different action. Your teammate might later question why you didn’t pass the ball. You might react negatively to your teammate’s accusations and demand to know why they didn’t yell “ball!” to indicate being ready to receive the ball. You can see by this example that when good communication happens, the possibilities for high performance are endless. But when communication is poor, the likelihood for shared understanding and high performance decreases significantly.

When we examine communication and diversity in the Canadian workplace, we have to understand that miscommunication will usually reveal itself in the way the message is encoded or decoded. In order to understand how to communicate more effectively interpersonally, we need to develop our abilities in better understanding ourselves, the situation at hand, and others.

Interpersonal Miscommunications

Why Diversity Matters

Diversity is defined as “the variety of characteristics that all persons possess, that distinguish them as individuals, and that identify them as belonging to a group or groups. It is a term used to encompass all the various differences among people commonly used in Canada and in the United States. Diversity programs and policies are aimed at reducing discrimination and promoting equality of opportunity and outcome for all groups. The dimensions of diversity include, but are not limited to, ancestry, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, physical and intellectual ability, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, type of area (urban/rural), age, faith and/or beliefs” (mygsa.ca, 2015).

This means that diversity is not about those other folks over there; it’s about you as well as them. It’s about all of us.

When done right and applied to people in a work or professional context, having diversity provides a competitive advantage for businesses and increased satisfaction for employees who can put their full potential to work. According to Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute (Ryerson University, 2015), the business case for diversity in Canada has several strong points.

First, diversity from more immigrants from non-traditional countries can stem the skills, talent, and population shortage.

Second, diverse people can have better understanding and connections to a bigger variety of domestic and global markets.

Third, studies have shown that diverse teams are more creative and innovative and thus deliver higher value.

Fourth, diversity can increase both employee and customer satisfaction while reducing lawsuits and increasing overall public reputation.

Finally, diversity has been shown to improve company performance and result in increased shareholder value.

Diversity matters because when we communicate with people who are different from us in a fundamental way, it can be difficult to go from miscommunication and misunderstanding to synergy and high performance in a business context. In an interpersonal context it is also difficult to make the leap from thinking the other person is “ridiculous” to challenging ourselves to develop our skills in listening and empathy before leaping to dismissive judgement. In order to get there, we must understand a bit more about our context in Canada.

Diversity in Canada

This land mass, North America, is called Turtle Island by many Aboriginal people. As the indigenous people of what is now called Canada, Aboriginal peoples—including Inuit, First Nations, and Métis—argue that they have collective entitlements that were never extinguished. This is to say that in some circles the very notion of “Canada” is a contentious issue.

When trading relationships between Aboriginals and Europeans led to mass immigration through imperial colonialism, the landscape was changed, and we became a treaty nation.

Settlers primarily from France and Britain, and former Loyalists—including some black people—from what is now the United States, have been in Canada for generations as have others (in comparatively smaller numbers) like the Japanese and Chinese people. France was the first dominant colonial group, and they were ultimately displaced by the British.

Canada is a constitutional monarchy that retains the Queen of Britain as the head of state; before confederation, Canada was a British colony. Overseas immigration to Canada used to exclude any non-Europeans as a matter of policy with institutional and societal support, with some exceptions. Over time, it can be argued that Canada is getting better at becoming a place where all residents and citizens can feel at home.

Since the 1970s, Canada has had an official policy of multiculturalism. This policy says people do not have to give up parts of their identity or their culture such as their religion, language, or customs, provided that they don’t interfere with others’ rights and freedoms as defined in Canada’s Constitution or Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In 2017, The Globe and Mail took to the streets to poll Canadians on multiculturism. Click through to watch the 6 minute video:

Canada’s official multicultural policy lends itself nicely to the notion of diversity. Canada is often described as a mosaic, in contrast to the melting pot philosophy of the United States to the south. Where the melting pot expects people to blend in, assimilate, and become “American,” the Canadian mosaic identity is arguably more fluid, enabling people to retain their cultures, customs, traditions, or other elements of their heritage. Not everyone is thrilled with this policy. Some people feel that too much difference creates too many divisions and too much confusion resulting in a national identity crisis. But in the famous words of Marshall McLuhan, “Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.”

Demographics

Editor’s note: All statistical information and graphs in the following sections have been reproduced from Statistics Canada (statcan.gc.ca).

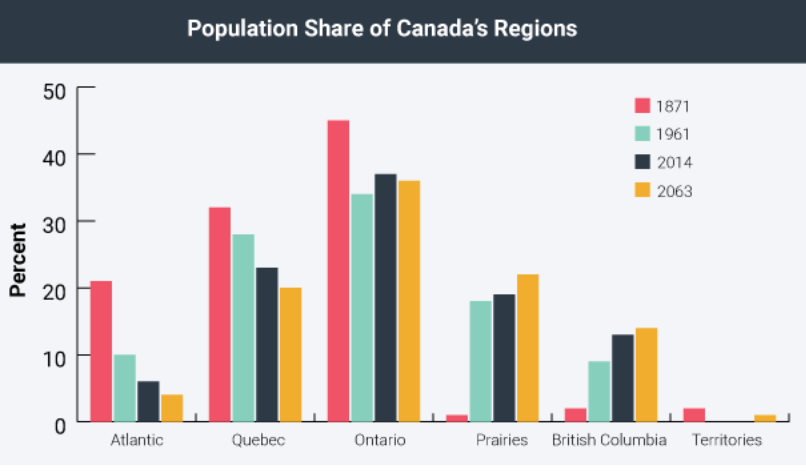

Throughout Canada’s history, changes in population growth and age structure have had many repercussions for Canadian society, for example on infrastructure needs, social programs, and the political influence of the various regions of the country.

As demographic trends—some recent, such as negative natural increases or the significant contribution of international immigration to population growth of some regions—will continue to shape Canada in the coming years, it is important to shed light on how these changes will affect the various regions of the country if current trends continue. Certain recent trends will probably affect many other aspects of Canadian society, such as ethnocultural and linguistic diversity.

Adapted from Statistics Canada (2015)

In 1961, the population share of the Atlantic provinces was higher than that of British Columbia (10 percent versus 9 percent), and only 5 percentage points separated the population shares of Quebec (29 percent) and Ontario (34 percent).

In 2014, the Atlantic provinces made up 7 percent of Canada’s entire population. Nearly two in five Canadians lived in Ontario (39 percent), and the difference between this province and Quebec (23 percent) had increased to 16 percentage points. Lastly, in 2008, the population share of the provinces west of Ontario became higher (31 percent) than the share of the provinces east of Ontario (30 percent) for the first time in the history of the country.

If the recent demographic trends remain steady until 2063, or nearly 200 years after Confederation, the population share of the Prairie provinces (24 percent) could exceed that of Quebec (21 percent). The Atlantic provinces’ weight could represent less than 5 percent of Canada’s population, while the population share of Ontario could decrease slightly.

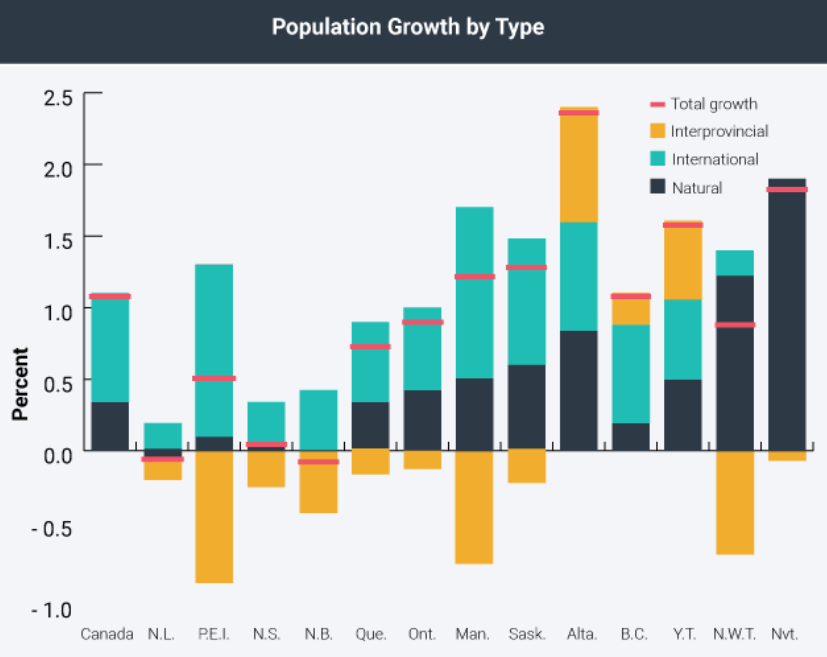

Adapted from Statistics Canada (2015)

Population growth in the provinces and territories can be broken down into three factors: natural increase, international migratory increase, and interprovincial migratory increase.

At the national level, approximately two-thirds of population growth is currently the result of international migratory increase, while the other third is a result of natural increase—notably because of a low fertility rate fluctuating around an annual average of approximately 1.6 children per woman.

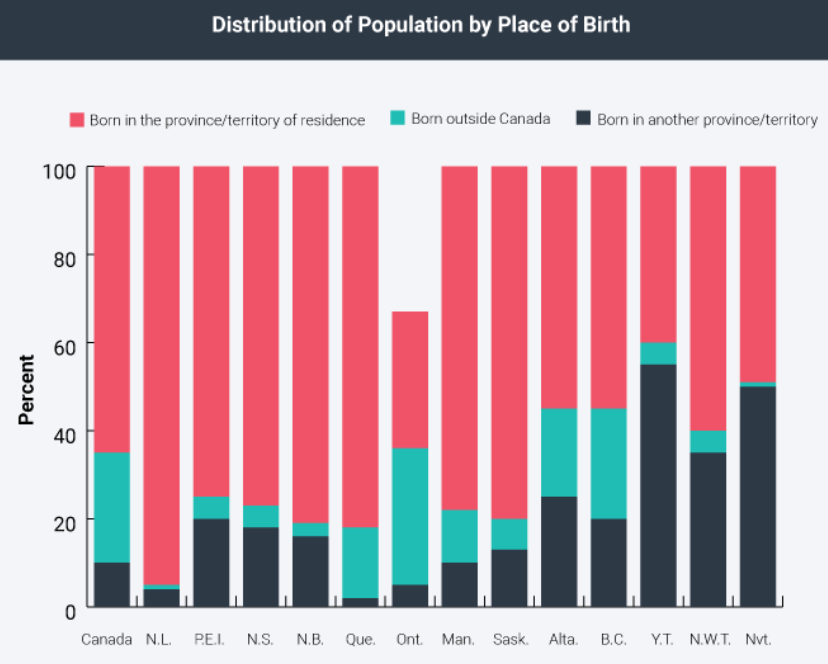

Adapted from Statistics Canada (2011)

The disparity in the sources of population growth from one province or territory led to differences in the population profile of provinces and territories.

Population composition by birthplace, which depends on the magnitude of international and interprovincial migratory increases, is a case in point. According to the 2011 National Household Survey, approximately one in two individuals living in British Columbia (51 percent) and Alberta (46 percent) were born outside these provinces (i.e., abroad or in another Canadian province or territory).

While natural increase trends are mostly predictable (because they are partially linked to changes in the age structure of the population), the trends associated with international and interprovincial migratory increases are more difficult to predict because they are more likely to be associated with changes in the economy. Many studies have shown the links between migration and the labour market.

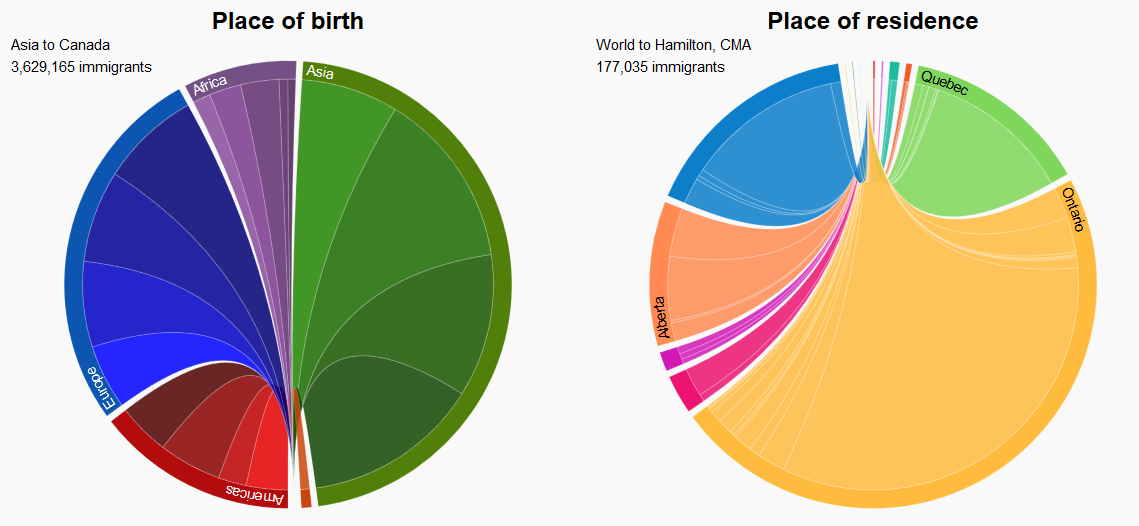

Stats Can offers an interesting, interactive chart of immigrant population. With a hover or a click, you can see from where new Canadians are arriving and to where they are settling.

If the various components of population growth (fertility, mortality, immigration, emigration, and interprovincial migration) remained steady in the coming years, however, the age structure and ethnocultural diversity of the various provinces and territories could become increasingly different. In addition, the population share of the provinces and territories could change considerably in the next 50 years, making for a very different Canada than today’s or at the time of Confederation.

This demographic and diversity information helps to underscore the amount of change that has happened and the amount of change that is likely to continue. Understanding the environment and context behind the increasing likelihood of having to work with diverse people from other provinces/territories, countries, as well as people with different languages, ages, or ethnicities is important for interpersonal communication skills development.

Key Diversity-Related Concepts and Definitions

When trying to understand how to more effectively encode and decode messages, it’s important to understand that people’s identities are diverse and complex, often shaped by their environment, history, and experience. We sometimes generalize in order to make sense of or evaluate a situation, but being mindful and listening carefully will help us do a better job of responding to a situation case-by-case instead of falling back on discriminatory or racist attitudes, bias, or stereotyping. We’ll look at each one of these in turn, but the first step is to understand what culture is.

Culture has more than one definition, but for our purposes it means the attitudes and behaviour characteristic of a particular social group (OxfordDictionaries.com, 2015). We are usually unaware of our patterns of behaviour and simply consider the way we approach things to be “normal” or common sense. When we encounter something or someone that/who does not fit with our notion of normal or correct, communicating interpersonally in that situation or with that person can become more difficult or complex. Some people belong to a dominant cultural group, defined as “a group that is considered the most powerful and privileged of all groups in a particular society or context and that exercises that power through a variety of means (economic, social, political etc)” (mygsa.ca, 2015). Other people may belong to a non-dominant cultural or minority group. “The concept ‘minority group’ does not refer to demographic numbers, but is used for any group [that] is disadvantaged, underprivileged, excluded, discriminated against, or exploited. As a collective group, a minority occupies a subordinate status in society” (mygsa.ca, 2015). These concepts about culture, particularly dominant versus non-dominant cultures, are important to our understanding that in the workplace, interpersonal communication takes place against a backdrop of these influences and affects the way people perceive, give, and receive messages.

Discrimination in the workplace can take many forms. Discrimination is defined as “the unequal treatment of groups or individuals with a history of marginalization either by a person or a group or an institution which, through the denial of certain rights, results in inequality, subordination and/or deprivation of political, education, social, economic, and cultural rights” (mygsa.ca, 2015). For example, a female board member once told the author that after board meetings in previous decades, all the other board members—all men—would go socialize afterwards, typically to play golf. When she tried to join them, they said, “These excursions are just ‘for the boys’ …. You understand, right?”

When you have a mix of prejudice and power leading one group (the dominant or majority group) to dominate over and exploit another (the non-dominant, minority or racialized group), you have racism, which asserts that the one group is supreme and superior while the other is inferior. Racism is any individual action, or institutional practice backed by institutional power that subordinates people because of their colour or ethnicity. Race is defined as a socially created category to classify humankind according to common ancestry or descent, and relies on differentiation by general physical or cultural characteristics such as colour of skin and eyes, hair type, historical experience, and facial features. Race is often confused with ethnicity (a group of people who share a particular cultural heritage or background); there may be several ethnic groups within a racial group (mygsa.ca, 2015). Racism in the modern Canadian workplace can show up in many ways and be either intentional or unintentional, from screening out or prioritizing certain names on résumes to assuming the racialized person in the room is the server or assistant. For many people in Canada’s dominant group, being called a racist is a tremendous insult that can immediately shut down communication. Ironically, the power to shut down or ignore communication related to racial discrimination is a racist act. People with good interpersonal communication skills can navigate their discomfort long enough to focus on listening, reflecting, and collaborating to find solutions.

Bias is subjective opinion, preference, prejudice, or inclination, either for or against an individual or group, formed without reasonable justification that influences an individual’s or group’s ability to evaluate a particular situation objectively or accurately (mygsa.ca, 2015). Many people in the workplace are unaware of the biases they may have, which is why self-reflection is such an important part of how to improve interpersonal communication through self-awareness.

Similarly, a stereotype is a false or generalized, and usually negative, conception of a group of people that results in the unconscious or conscious categorization of each member of that group, without regard for individual differences (mygsa.ca, 2015). When we learn about other groups of people, it’s easy to forget that individuals make up groups. For good interpersonal communication to occur, it is important to be open, to listen, and to recognize that person as a unique individual.

Understanding how culture, discrimination, stereotypes, and bias affect the workplace and how people communicate are essential to understanding the move toward inclusive practices. These days when you hear about diversity, you also hear about inclusion. Inclusion means acknowledging and respecting diversity. It is an approach based on the principles of accepting and including all people, honouring diversity, and respecting all individuals (mygsa.ca, 2015).

Types of Diversity

Below, we highlight the following types of diversity:

Religion and Culture

Scenario

Culture may well be the first type of diversity that comes to mind, and with good reason! As a resident of Canada, you live in one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world, and you are probably already encountering people from different cultural and religious backgrounds every day. If you consider Canada’s history, you’ll recognize that, with the exception of the First Nations and Inuit populations, most modern-day Canadians come from families that came to the country from elsewhere. As mentioned earlier, historically, most Canadian settlers came from Europe, although the Middle East and Asia are now our largest source of newcomers (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Language

The English language has unfortunately developed many pejorative terms for people of various religions and ethnicities. When choosing a word to refer to a religious or ethnic group, your best choice is usually to use the term that the community uses to refer to itself. The table below will help you find the preferred word for some of the more commonly confused cultural and religious labels, but please keep in mind that this is only a small sampling of possible terms and ethnicities.

Benefits

Religious and cultural diversity can benefit an organization in a number of ways, including the following:

- Happier employees (when the organization shows respect for differences)

- Increased productivity, innovation, and profit (employees are able to bring what they have learned about other ways of doing things to their roles)

- A wider talent pool (if the organization hires internationally, they have more access to highly experienced people)

- The ability to represent and speak for the company’s target audience(s) (and, therefore, develop products and services that will fit their needs)

Challenges

One of the main challenges you might experience in a diverse workplace, whether differences are cultural or otherwise, is resistance to change. There will always be a few peoplewho are not as open minded or flexible. For these people, it may be difficult, at first, to take advantage of all the benefits that diversity can bring. For example, consider the following scenario.

The Intercultural Workplace

Claire, from Canada, decides to take a year off between high school and university. She visits England for a year, to work and travel. During her time in England, Claire takes a temporary job at a large corporation in Manchester. As Administrative Assistant to the Vice-President, Claire spends a lot of time managing communication between her office and the offices of the other executives who are stationed around the country. She finds herself juggling hundreds of emails and phone calls per week, most of which are from colleagues with a question or two.

After experiencing this “communication overload” for a few months, Claire attends a meeting. One of the managers asks if anyone has anything to discuss. Claire mentions that there seem to be some communication problems, with a significant volume of email and phone calls leaving little time for productive work. She explains that at her previous workplace, staff used an online collaboration tool to exchange quick messages with one another. She says that once everyone got used to using the tool and keeping it open throughout their work day, the volume of emails and phone calls were significantly reduced, and workers were able to get more done in their day. Claire suggests that they try out this new tool for a one-month trial period to see if it can help with the problems they are experiencing.

Claire looks around as she is explaining this, and most of her colleagues are nodding and taking notes. However, when she finishes her explanation, one of the senior managers quickly jumps in to say, “No, I don’t think that’s for us. We’ve always done things by email, so I can’t see us changing things now.”

Claire is discouraged. Being the “new girl” and from a different country, she was nervous about speaking up, but, in her previous experience in Canada, employees have been encouraged to make suggestions when processes are not working, so she felt that she could help out by doing so here. But even though she doesn’t feel different from her British colleagues, Claire has some unfamiliar interpersonal challenges to navigate.

When discussing the incident with a co-worker later on, Claire realizes that in the UK employees are, generally, a little more reserved and not likely to suggest that managers are doing anything “wrong”—at least not directly. Politeness and subtlety is key in this culture, so Claire’s direct communication style is something that British workers are not as accustomed to. Her co-worker also mentions that the manager who dismissed Claire’s idea has been with the company for over 30 years and is probably “set in her ways.” Here Claire’s challenges are twofold: she is experiencing a combination of intercultural and intergenerational differences.

In this case, even though many members of staff were in favour of Claire’s idea, it was not approved, as the manager in question did not support it.

Strategies

To communicate effectively in a culturally diverse workplace, adopt the following tips and techniques:

- Avoid jargon and slang in verbal and written communication, as these are often specific to a cultural group or location. Using these can alienate people and cause misunderstandings.

- Assign or become a mentor to new employees. This will help with integration and communication of the company’s processes, vision, and values.

- Facilitate (and take part in) professional development opportunities. When people work together to solve a problem or learn something new, this creates bonds and allows sharing of ideas.

- Practise active listening.

- Be aware of your own biases and privileges, and be open to new points of view.

- Know your audience! As in all other communication practices, this key piece of advice is important here, too. Ask yourself, What does my audience know or perceive about my topic? By thinking about your audience ahead of time, you may be able to foresee and prevent misunderstandings or objections.

Linguistic

Scenario

English may be the most widely spoken language around the world, but there are more native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and Spanish than there are native English speakers. In the West, we take for granted the bias towards English-speaking people. English is commonly used as the default language in business sectors from science to the maritime industries and aeronautics. It is estimated that 53.8 percent of the Internet’s top websites are written in English (W3 Techs, 2016).

But we cannot assume that everyone we work with will be a native English-speaker or will be able to speak English at all. In Canada, linguistic barriers can be particularly challenging because we have two official languages: English (56.9 percent of the population are native-speakers) and French (21.3 percent) (Statistics Canada, 2011). Our territories use various languages belonging to Aboriginal groups. Add to that the multitude of languages used by people from the many ethnicities that make up our cultural mosaic, and the likelihood of common interactions with non-native English speakers increases further.

In Quebec, 78.9 percent of the population have French as a mother tongue, while only 8.3 percent are native English speakers; however, 42.6 percent of the province’s population have a knowledge of both official languages (Statistics Canada, 2011). French is legally the official language and must be used in the public sector and public relations. Nationally, signage and packaging display both English and French messaging. In New Brunswick, our only officially bilingual province, 65.5 percent of the population are native English speakers, while 31.9 percent are French speakers (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Language

Have you ever casually mentioned, “He doesn’t speak English,” “She isn’t from here,” or “He won’t understand,” when referring to an English-language learner or speaker of a language other than English? Phrases like this are often said without malice, but they can come across as dismissive of the person’s efforts to communicate. Be sensitive about the way that you refer to people who speak a language other than your own. Chances are they’d love to be able to speak English as well as you do and are making efforts to learn, but this doesn’t happen overnight!

Benefits

Linguistic diversity and multilingualism is a major benefit to the Canadian workplace, because our country has two official languages. Knowing a second-language improves your ability to communicate with a wider range of people, enriching communication and collaboration in your workplace. Knowing a second language can also improve your career prospects. You’ll have more opportunities to work internationally, and, if you want to work in the public sector in Canada, bilingualism is often a requirement.

Challenges

The key challenge in this situation is avoiding misunderstandings. These can occur in a few different ways. First, the non-native speaker may lack the vocabulary to explain to you what they need or want. But second, you might find yourself tempted to make assumptions or even to fill in words or finish their sentences for them, which, in most contexts, will demonstrate your impatience and come across as rude in most contexts.

Another challenge in the linguistically diverse workplace is that while those who share a language will enjoy speaking to one another in their native tongue, this can make other workers and customers feel excluded. If people are conversing in front of you in a language that you don’t understand, you might worry that something negative is being said.

Strategies

Before you find yourself thinking, This person’s English isn’t very good, consider, how well can you speak their native language, be it Japanese, Hungarian, or Bengali? In most cases, you will find that non-native English speakers around the world work hard to learn even a little bit of English—it is those of us in the West who are generally less competent with other languages, mostly because we don’t have the same need to use them in our daily interactions. Because of the English language bias we mentioned earlier, speakers of other languages may perceive that opportunities will be greater if they can speak some English. So, show some appreciation that the person is making an effort to communicate with you! This goes a long way.

If you are struggling to communicate with someone who does not speak English, try having them write down what they need to say, as this may make it easier. If you are trying to explain a set of instructions, for example, you could try using gestures or even drawing a diagram or picture. It’s amazing what you can communicate with a few stick people, if you need to! In this context, body language and tone are very important. The other person may not understand everything you are saying, but they can tell from your body language, expressions, and vocal tone what the mood of your message is. For this reason, do a quick self-check on your own frustration level, as you will want to keep any annoyance or frustration hidden. If you have access to a computer or mobile device, these can come in very handy, as you can type in what you need to say in a translation application (e.g., Google Translate). Though the translation may not be grammatically correct, you can usually get the essential meaning across.

Communicating Through Language Barriers

In many ways the world has become a lot smaller over the last few years. As technology increases our capacity to communicate with anyone at any time, our workplaces are becoming increasingly globalized. One of our authors works in digital technology and spends a lot of time working with computer programmers who are working from all over the world. She often has to instruct a non-native English speakers on highly technical details via text-based communication. When she does this, she is typically on the opposite side of the world and has never met the programmer face-to-face.

The following are some of the tips she has learned over time to help with this:

- Write down the steps to take, in order

- Give instructions in writing instead of (or in addition to) verbal instructions. It is easier for ESL speakers to follow written text as they can look up (or use a translation app) on any words they don’t understand. They can also refer to the document later and are less likely to miss steps.

- Use plain language

- Ask the recipient to respond with a list of tasks they will undertake, and their expected completion

- If you are working on something visual, use a screen-sharing application or take screenshots—it’s very difficult to collaborate on things like this unless you are both looking at the same thing, at the same time

- Take advantage of video chat tools like Skype and Google Hangouts. These provide more information richness so that misunderstandings are less likely

- Look for some common ground. For example, she says, “I worked with a programmer whose favourite television show was also one of mine. We shared quips and references that made us laugh, so our communication became friendlier and more relaxed.”

Gender

Scenario

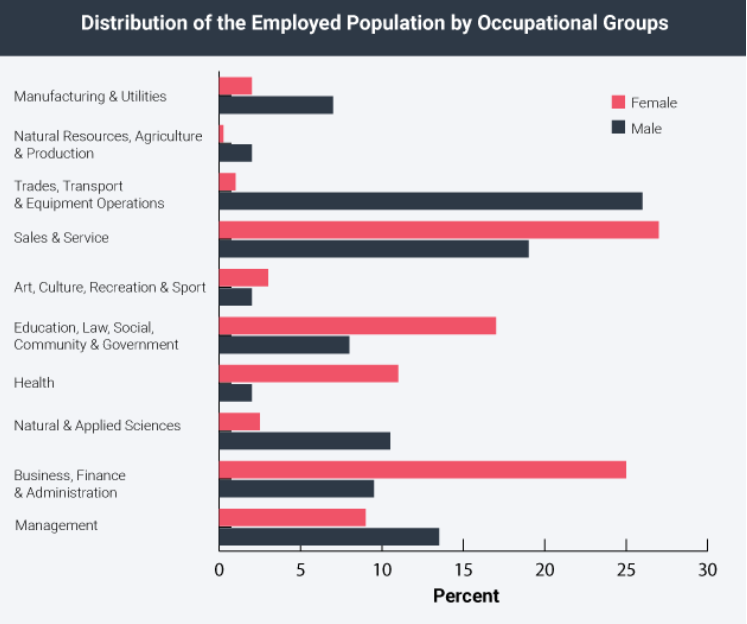

Men and women make up nearly equal proportions of working Canadians. In 2011, women comprised 48 percent of the labour force. When occupations were considered, men and women were noticeably involved in different types of roles, as you can see from the graph below (Statistics Canada, 2013). This split contributes to the challenges that both genders face when they choose to enter fields traditionally thought of as male- or female-dominated professions.

Adapted from Statistics Canada (2013)

Language

One key to avoiding gendered bias in language is to avoid the generic use of he when referring to something relevant to both males and females. Instead, you can informally use a gender-neutral pronoun like they or their, or you can use his or her (American Psychological Association, 2010). When giving a series of examples, you can alternate usage of masculine and feminine pronouns, switching with each example.

We have gendered associations with certain occupations or activities that tend to be male- or female-dominated. The following word pairs show the gender-biased term followed by an unbiased term:

- waitress → server

- chairman → chair or chairperson

- mankind → humankind or people

- cameraman →camera operator

- mailman → postal worker

- sportsmanship → fair play

Common language practices also tend to infantilize women but not men, when, for example, women are referred to as chicks, girls, or babes. In addition, titles of address that precede names are used to indicate women’s marital status, whereas no such distinction exists for men (i.e., Miss/Mrs. versus only Mr.). Since there is no linguistic equivalent to indicate the marital status of men, using Ms.—which does not denote marital status—instead of Miss or Mrs. helps to reduce bias.

Benefits

A gender-diverse workforce has a number of benefits that not only improve working conditions for employees but also improve the bottom-line for the organization. Men and women have different views, strengths, and insights. By making the best use of these differences, companies can do a better job of problem solving and innovating. Equal representation of males and females inside the company also benefits those outside it—particularly the customers and clients, as the company can more accurately understand what the market wants and needs. Having a reputation for gender diversity also has positive benefits when it comes to public relations and recruitment. Increasingly, people want to work for companies that are making positive moves in this regard. It is not in an organization’s best interest to ignore nearly half of its prospective talent pool when competition for the best and brightest employees is only increasing.

Challenges

Two issues that can cause conflict between men and women in the workplace are the earnings gap and the glass ceiling. According to the Pay Equity Commission, Ontario statistics show that men in full-time employment earn an average of 26 percent more than women do (Pay Equity Commission, 2011). The following are some potential explanations:

- Women are more likely to have gaps in their résumes as a result of taking time off to have children.

- Women are underrepresented in high-earning occupations like business and engineering.

- Traits more often associated with men, such as assertiveness and negotiating skills, are valued in higher-ranking roles, so women are less likely to be hired for these or promoted into them.

These explanations do not account for gender differences in pay when the roles and responsibilities are the same, however. Gender discrimination lawsuits are an unfortunate reality and, in these cases, discrimination against women does appear to be the primary factor.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. have had several incidences of alleged gender discrimination. One of the people who initiated a lawsuit against them in the early 2000s was a female assistant manager who found out that a male assistant manager with similar qualifications was making $10,000 more per year. When she approached the store manager, she was told that the male manager had a “wife and kids to support.” She was then asked to submit a household budget to justify a raise (Daniels, 2003). Such discrimination contributes to an unfair work environment and results in conflict between men and women in the workplace.

The glass ceiling is another term that you may be familiar with. It refers to the idea that women are less likely to get promoted to higher management roles. Though women represent close to one-half of the workforce, men are four times more likely to reach the highest levels of organizations (Umphress et. al, 2008).

Traditionally, men have been viewed as more assertive and confident than women, while women have been viewed as more passive and submissive, making them less likely to be considered a fit for a management role. Stereotypes also influence how employees’ accomplishments are viewed. For example, when men and women work together in a team on a “masculine” task such as working on an investment portfolio and it is not clear which member has contributed what, managers are more likely to attribute successes to the male employees (Heilman et. al, 2005). In addition to contributing to the team, female employees must also work harder to communicate their contributions to superiors.

Strategies

The more that employees know about gender inequalities, the more likely they are to effect change. So, to create a more inclusive workplace, individuals would do well to set up, contribute to or attend opportunities for professional development (e.g., workshops and panel discussions) that focus on this area. Workplaces that establish and promote gender equality goals, such as an aim to have women in a certain percentage of management roles, will create interest and conversation between employees. As part of this, you can champion female leadership by holding talks and sharing success stories of female-led working groups within and external to the company. If your workplace doesn’t already offer these, look for opportunities to run and attend social events that give male and female employees an opportunity to mix, such as book clubs, fitness groups, or fundraising events.

Sexual Orientation

Scenario

A forum research poll released in 2012 found that 5% of the Canadian population identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. The 2016 census recorded 72, 880 same-sex couples, representing 0.9% of all couples. From 2006 to 2016, the number of same-sex couples increased much more rapidly (+60.7%) than the number of opposite-sex couples (+9.6%). In 1999, Canada recognized same-sex couples as common-law partners, providing a legal status similar to that of heterosexual common-law couples. In 2005, Canada legalized same-sex marriage; and by 2016 one in eight same-sex couples (12.0%) had children living with them compared with about half of opposite-sex couples.

Language

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s preference for sexual relationships with individuals of the other sex (heterosexuality), one’s own sex (homosexuality), or both sexes (bisexuality). The term also refers to transgender individuals, those whose behaviour, appearance, and/or gender identity departs from conventional norms. Transgendered individuals include transvestites (those who dress in the clothing of the opposite sex) and transsexuals (those whose gender identity differs from their physiological sex and who sometimes undergo a sex change). A transgender woman is a person who was born biologically as a male and becomes a woman, while a transgender man is a person who was born biologically as a woman and becomes a man. Gay is the common term now used for any homosexual individual; gay men or gays is the common term used for homosexual men, while lesbian is the common term used for homosexual women. All the types of social orientation just outlined are often collectively referred to by the shorthand LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) or LGBTQ (includes the term queer/questioning, and the T can also refer to twin-spirited as well as transgender). The term straight is used today as a synonym for heterosexual.

LGBTQ people are often the recipients of insensitive language. Much of this is the result of misunderstanding on the part of straight people, who may use the incorrect terminology simply because they are not familiar with the community’s preferred definitions. However, there are occasions where language misuse can be hurtful or offensive. For example, the use of the word gay as a casual insult when speaking about someone or something bad or undesirable is offensive and should be avoided.

Another challenge here is to avoid heterosexual bias. For example, do not make assumptions about sexual orientation when addressing a colleague. Rather than saying, “Is your wife coming to the staff Christmas party?” you might ask, “Are you bringing a date to the staff Christmas party?” In communication about activities attributed more commonly to straight people, such as parenting, you should also avoid heterosexual bias. For example, rather than branding your event “The Annual Father–Daughter Picnic,” you might instead create a more open and inclusive event by terming it “The Annual Parent–Child Picnic.” This way, you can avoid unintentionally excluding LGBTQ people who may feel unwelcome if other terms were used.

Benefits

A diverse group of staff that includes LGBTQ people creates, within an organization, a more accurate representation of the public. In order to develop products and services for an increasingly diverse market, organizations can benefit from the insights that exist here. Inclusion of LGBTQ people also comes with an economic benefit. LGBTQ people make up a potentially high-value demographic. Cohabiting same-sex couples are statistically more likely to have a two-income household with no children than heterosexual couples are, so their purchasing power is increasingly one that companies selling consumer products and services want to target.

Challenges

In many parts of Canada, society has become increasingly liberal in recent years. Tolerance and acceptance of LGBTQ people has generally increased, as the stigma associated with non-heterosexual orientations gradually fades. But people in this demographic still face a whole host of challenges. For example, it was not until 1992 that a law was changed to allow LGBTQ people to serve in the Canadian military without harassment or discrimination. In some professions, for example those that are traditionally male-dominated, LGBTQ people may still not feel comfortable sharing their sexual orientation with work colleagues, a fact that implements an immediate communication barrier.

Much of the challenge of integration that LGBTQ people experience stems from the prejudice, misunderstanding, and discomfort on the part of heterosexual people. When you don’t know someone well, you may not know how they will react to a great many things, from your value system and opinions, to something far more personal like your sexual orientation. For this reason, many LGBTQ people may choose to keep their orientation private at work, regardless of the industry they work in. Some religions have strong anti-LGBTQ biases, which may put LGBTQ people who work in religiously oriented organizations such as schools and charities backed by religious groups, in a difficult position. LGBTQ people remain vulnerable to bullying, depression, and other issues because of the outside pressures and stigmas that remain present in some segments of society.

Strategies

How can organizations show their respect for diversity in sexual orientation? It all starts with communication! Some companies start by creating a written statement that the organization will not tolerate discrimination based on sexual orientation. They may have workshops addressing issues relating to sexual orientation and facilitate and create networking opportunities for LGBTQ employees. Perhaps the most powerful way in which companies show respect for sexual orientation diversity is by extending benefits to the partners of same-sex couples. Research shows that in companies that have these types of programs, discrimination based on sexual orientation is less frequent, and the job satisfaction and commitment levels are higher (Button, 2001)

Generation and Age

Scenario

Until recently, workplaces had been managed and staffed mostly by Baby Boomers and those from Generation X. People from these generations tend to view diversity as an issue of fairness and equality. For them, a diverse workplace is important because it is legally required and the right thing to do but is not always truly supported or encouraged by management and staff. Millennials—loosely defined as the generation born between the late 1970s and the early 2000s—will make up the largest proportion of the worldwide workforce by 2025. Their views on what makes a happy and productive workplace are vastly different than the views of the generations that came before them, as are their preferred working styles.

Language

Language that includes age bias can be directed toward older or younger people. Descriptions of younger people often presume recklessness or inexperience, while those of older people presume frailty or disconnection. The term elderly generally refers to people over 65, but it has connotations of weakness, which isn’t accurate, because there are plenty of people over 65 who are stronger and more athletic than people in their 20s and 30s. Though it’s generic, the term older people doesn’t have the same negative implications. Additionally, referring to people over the age of 18 as boys or girls isn’t typically viewed as appropriate.

Benefits

Research shows that age is correlated with a number of positive workplace behaviours, including higher levels of citizenship behaviours such as volunteering, higher compliance with safety rules, lower work injuries, lower counterproductive behaviours, and lower rates of tardiness or absenteeism (Ng and Feldman, 2008). Having representation from multiple generations on your team will also help you to avoid the dreaded groupthink, a term with which you may be familiar; it essentially means that in an attempt to avoid conflict, groups can agree on flawed decisions because they are trying so hard not to offend, criticize, or discredit members’ ideas, or because they share biases, values, and ideas that do not leave room for alternative points of view.

Have you noticed that Western culture tends to value youth? This is to our detriment, particularly in the workplace, as the older people in our society can be great sources of information. When you have longer-serving employees on your team, you have the benefit of their experience—you can avoid repeating mistakes that the organization has made in the past. Generation X’ers can help to bridge the gap between baby boomers and millennials, facilitating better communication on teams.

Challenges

Different generations have different preferences with respect to communication processes. For example, baby boomers prefer face-to-face communication, while millennials prefer short text-based communications (instant messaging, for example). Millennials tend to be more team-oriented and prefer a collaborative environment, whereas baby boomers prefer to work in a more solitary manner.

Strategies

The pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk Inc. noticed that baby boomers were competitive and preferred individual feedback on performance, while Generation Y workers were more team oriented. This difference led one regional manager to start each performance feedback e-mail with recognition of team performance, which was later followed by feedback on individual performance. Similarly, Lockheed Martin Corporation noticed that employees from different generations had different learning styles, with older employees preferring PowerPoint presentations and younger employees preferring more interactive learning (White, 2008). Paying attention to such differences and tailoring various aspects of communication to the particular employees in question may lead to more effective communication in an age-diverse workforce.

Socioeconomic

Scenario

In Canada, 8.8 percent of the population are considered to be in low-income, after tax (Statistics Canada, 2013). The low-income cut-off for a four-person family in Canada is relative and based on the percentage of income a family would need to spend on basic needs. As an example, in 2011, the after-tax cut-off for a family of four living in a community with a population between 30,000 and 99,999 people is $30,487 per annum (Statistics Canada, 2015). People on low incomes also tend to be more likely to suffer from other demographic disadvantages, such as low levels of education and poor health.

But even if you are not part of the low-income demographic, economic status differences are still likely to play a role in your professional life. Around the world, the gap between the wealthy and poor is widening, and the middle class is shrinking. The global markets have still not entirely recovered from the recession of the 2000s, and a steady drop in oil prices have made their mark, particularly in Canada. It does not take long to go from affluent to economically disadvantaged when global forces are in play. There are increasing tensions between the rich and the poor around the world, with social movements like Occupy gaining traction. Even within your own social group or workplace, this divide may be obvious—for example, between high-earning upper management and the relatively low-earning working classes.

Language

Derogatory terms are an unfortunate reality for low-income demographics. Use of terms like ghetto and trailer trash are offensive and should be avoided. As in all communication, consider your audience! Before you use words that have the potential to offend, recognize that a simple slip of the tongue, even if it is not meant with malice, can cause hurt feelings, discomfort, and embarrassment.

Benefits

As with most of the diversity types we have discussed, the more an organization resembles the makeup of the market it targets, the more likely it is to be able to respond to demands from this demographic. Mixing people with different worldviews provides an opportunity to learn from their experiences. It is tempting to think that solutions to big problems will come from the highly educated few at the top and trickle down, but this is often not the case. People who experience challenges in life often develop resourcefulness in order to overcome them—a desirable trait in any worker.

You may have heard stories of people who came from a disadvantaged background only to credit their later success to the life skills they learned in more trying times. Famous names, such as Oprah Winfrey, Leonardo DiCaprio, J. K. Rowling, and many others, experienced economic disadvantages that paved the way for the success they now have.

Challenges

People who struggle to meet their own basic needs, for example, food, clothing, and shelter, often miss out on the opportunities given to people in better economic situations. For example, a middle- or upper-class young person typically has an easier time getting into post-secondary education than their low-income counterparts because their primary and secondary education has been of a better quality. They have been able to access after-school programs and tutors, if ever they needed to. They most likely had access to books, the Internet, and educational experiences growing up, many of which may be out of reach for young people from low-income families. These advantages carry over into their working lives. While higher-income individuals have opportunities to go to university, network with people who can help them in their careers, and take on jobs and internships to build a high-quality résume, the same cannot necessarily be said for those on a lower income.

Many people do not realize the prejudice they hold, when it comes to poverty. There is a widespread belief that poverty is equated with laziness, or that people of a lower socioeconomic status are entirely responsible for their circumstances. When considering another person’s economic situation, remember that many people who are of lower incomes have experienced considerable challenges in life. For example, many people struggle financially because of relationship and family breakdowns, illness, lack of educational opportunities, or other misfortunes that you may not be able to see or understand.

Just because someone works in a similar role to you does not mean that their earnings or disposable income is the same as yours. In the workplace there can be a lot of pressure on people of lower economic status to spend money in order to be included in the social aspects of the workplace. For example, do your colleagues go out for drinks when it is someone’s birthday? Does your office hold a holiday party where the staff go out for a meal? While those staff members who are financially successful may not give these events a second thought, those who have socioeconomic challenges may not be able to attend, or may stretch themselves in order to be there and be included, even though they cannot afford to.

Strategies

Your organization can begin to address these challenges by paying a living wage to all employees. Doing so has positive benefits for the organization; for example, the organization will have access to a wider talent pool, as prospective employees are attracted to organizations that have policies such as this. It is also a way to gain positive media attention. Even if you are not a member of management who has the necessary power required to make such a significant change to the organization, you can champion the concept collectively with colleagues who support the move. Employer-subsidized programs such as meals and childcare at the office can also make an impact on the standard of living of employees.

Ability

Scenario

According to Statistics Canada (2015), over 11 percent of Canadians experience pain, mobility, or flexibility challenges. These can be severe enough to require a wheelchair or other mobility aid, or they can be less severe but still make it difficult for people to do jobs that require some type of movement or labour.

The next most common disability among Canadians was mental or psychological disabilities (3.9 percent). These commonly include depression and anxiety; however, a great many others exist that are less familiar to the general public.

Dexterity problems is the next most common category, affecting 3.5 percent of Canadians. Dexterity limits can affect a person’s motor function and can make moving around the worksite a challenge. It can also make it difficult for people to use computers and other digital devices.

About 5.9 percent of Canadians have some type of vision or hearing problem, be it total blindness or deafness, or partial use of these senses.

While other areas like memory, learning, and developmental disabilities can also pose barriers, specific tools and aids can be useful for employees with disabilities. For example, wheelchairs and arm supports can make movement possible, while hearing aids and magnifiers can make hearing or vision clearer. For people who are blind, interaction with computers is possible with the aid of screen readers and text-to-speech technology.

Language

People with disabilities are sometimes viewed as a cultural/social identity group. Those without disabilities are often referred to as able-bodied. As with sexual orientation, comparing people with disabilities to “normal” people implies that there is an agreed-upon definition of what “normal” is and, thus, that people with disabilities are “abnormal.” Disability is preferred to the word handicap. By ignoring the environment as the source of a handicap and placing it on the person, we reduce people with disabilities to their disability—for example, calling someone “a paraplegic” instead of “a person with paraplegia.” In many cases, verbally marking a person as disabled is unnecessary and potentially damaging. Language used in conjunction with disabilities also tends to portray people as victims of their disability and paint pictures of their lives as gloomy, unpleasant, or painful. Such descriptors are often generalizations or completely inaccurate.

Another set of troubling terms include the casual use of words and phrases like “crazy,” “He’s off his meds,” or “She’s a little OCD.” By using these terms, we are making light of serious mental health concerns. The casual way in which we use these for humorous effect is offensive to people who live with serious conditions, and can result in situations where you unknowingly “stick your foot in your mouth.” Mental health issues are often invisible, so you have no way of knowing that the people around you aren’t actually sufferers of these conditions. Perhaps they have a family member or friend who struggles with a mental illness and would be upset or offended by your comment.

Solidify your understanding of People First Language:

Benefits

People with ability challenges can be a significant boost to the ability of an organization to reach its market. Those who experience these things on a daily basis have an insight that able-bodied people cannot have.

For example, one of our authors taught a blind student who used a screen reader and text-to-speech technology to interact with computers in a course about digital technology. The speed at which the student could operate these devices often exceeded the speed of able-bodied students and even the teacher herself. The student was eager to share her perception of the world with her fellow students and, therefore, invited a guest to demonstrate a variety of tools used to make the Internet more accessible. As a result, the class was able to gain insight into this demographic and adjust their practices accordingly. The blind student’s goal was to become an accessibility consultant so that she could improve Internet access for people with challenges similar to hers. By undertaking this career path, the student will be able to develop user-friendly and inclusive designs to help organizations develop more inclusive business practices—a level of insight missing from the organizations that she works for.

Challenges

Environmental factors can play a part in making the work day of a disabled person more of a challenge than it should be. For example, you have probably been in older buildings that do not have elevators installed either because of the age of the building or space constraints. To an able-bodied employee, working in a office building like this may not be a problem. But for someone who uses a wheelchair, lack of an elevator can make even the seemingly simple task of sitting at a desk on the second floor, impossible. The costs of refitting a building or purchasing equipment to accommodate people with disabilities can be prohibitive for organizations. In addition, the ability to accommodate in a way that does not demean or hide people with disabilities is a challenge for organizations. For example, buildings that do not have ramps at the front entrance may instead fit an accessible entrance at the rear of the building. While this may not seem like a problem for the able-bodied person, a wheelchair user will need to access the building differently than others, which may bring up feelings of exclusion.

A main communication challenge that arises here is misunderstanding on the part of able-bodied people. Individuals without impairments cannot know what everyday life is like for a disabled person. Sometimes able-bodied people go out of their way to be accommodating out of awkwardness or because they don’t want to come across as prejudicial, but while most people will appreciate these efforts, most disabled persons have become accustomed to (and some have always lived with) their challenges and are capable of managing themselves as well as able-bodied people are. As such, a level of discomfort can arise because we are singling them out, even if our intentions are good. This is not to say that you should not be accommodating to a disabled person but simply that you should ask if there is anything you can do to help rather than taking over or micromanaging them.

Another factor to consider is that some disabilities are invisible. For example, perhaps you sit next to a person who suffers from a mental health issue or a learning disability or who experiences persistent pain, and you don’t know it. This can make pulling their own weight on a team challenging. Perhaps the disability leads them to miss work or struggle to complete tasks. Therefore, it is far better to ask what you can do to help than to react with frustration or conflict. Let the person take their time and show or tell you what they need.

Strategies

Supportive communication with others seems to be the key for making employees feel at home. Because the visible differences between individuals may act as an initial barrier against developing rapport, employees with disabilities and their co-workers may benefit from being proactive in relationship development (Colella & Varma, 2001).

Another key way to make a people with different abilities feel confident in the workplace is to consider accessibility. As a communications professional, this may come to your attention particularly when you are communicating via digital channels. For example, let’s assume that your workplace uses an intranet to deliver news, policy changes, employee education content, and other announcements. You’ll need to consider employees with disabilities, here, particularly those who have visual, hearing, or motor impairments. The following are some things you can do to accommodate this demographic:

- Make sure the intranet is fully accessible to screen readers and avoid using images in place of text, as screen readers cannot “read” images.

- Test your web pages with a colour-blindness simulator to ensure that colour-blind users will have a good experience.

- Provide text transcripts for all audio content and alongside videos.

- Make it easy to navigate pages by avoiding the need for a lot of clicking or precise mouse movements.

These are just a few suggestions, of course. Depending on the demographics of your staff, there will be many more accommodations you can make. But this should get you started on thinking about accessibility. Most of all, remember that not everyone has the luxury of being able-bodied and that not all illnesses and challenges are visible.

Communication Challenges

If managing diversity effectively has the potential to increase company performance, increase creativity, and create a more satisfied workforce, why aren’t all companies doing a better job of encouraging diversity? Despite all the potential advantages, there are also a number of challenges associated with increased levels of diversity in the workforce. Conflict can arise if staff members do not use some caution when working in this way. Here we will highlight two issues to watch out for.

Similarity-Attraction Phenomenon

Have you noticed that we tend to stick within groups of people who are similar to us? Naturally, we want to be around people who share our interests and values; we perceive safety and comfort in belonging. But this automatic, natural habit can mean that we miss out on many of the benefits that diversity can create. This pattern, the similarity-attraction phenomenon, begins at the door of organizations that hire individuals who are “similar” to the existing workforce.

For example, the technology sector is under increasing pressure to diversify its predominantly white-male workforce. This homogenous hiring habit not only results in fewer opportunities for women and minority groups but also means that the organization hires people with similar backgrounds, interests, and ideas. The workforce is less able to come up with new solutions to the problems they are trying to solve because their thought processes and points of reference are similar. This also limits their ability to authentically represent their audience. Consider a social networking technology startup, for example. How can a workforce consisting of highly educated white males accurately speak and develop services for growing audiences in South Asia or East Asia, where the education levels, economic status, race, religion, language, and cultural practices are far removed from what the employees experience themselves? These issues demonstrate why having a diverse workforce is so important.

Research shows that individuals communicate less frequently with those they perceive as being different from themselves (Chatman et. al, 1998). They are also more likely to experience emotional conflict with people who differ with respect to race, age, and gender (Jehn et. al, 1999; Pelled et. al, 1999). Individuals who are different from their team members are more likely to report perceptions of unfairness and feel that their contributions are ignored (Price et. al, 2006).

There are some simple things you can do to prevent this from becoming a source of conflict in your workplace. First, be a friendly and welcoming face for newcomers! If a new starter joins your team, invite them for coffee or offer to show them around. Something as simple as this can help to break down the divide between new and long-serving staff members and can create groups of colleagues with different experiences and backgrounds. Mentorship programs are also helpful here. If you have an opportunity to become a mentor or to be mentored, seek out someone with a different background or set of experiences than your own. This will create an equally beneficial relationship that leads both of you to learn something new.

Fault Lines

Another challenge that is particularly common in team-working scenarios is that groups often split into subgroups based on some common trait. For example, in a group composed of three females and three males, gender may act as a fault line, dividing the team in two. Further, imagine that the female members of the group are all over 50 years old and the male members are all younger than 25. In this case, age and gender combine to further divide the group.

Teams that are divided by fault lines experience a number of difficulties. For example, members of the different subgroups may avoid communicating with each other, reducing the overall cohesiveness of the team. These types of teams make less effective decisions and are less creative (Pearsall et. al, 2008; Sawyer et. al, 2006).

To prevent fault lines from becoming an issue in your workplace, look for ways to mix demographics within a team so that splitting into these obvious sub-groupings is not easy. Going back to our example of a team composed of three male and three female members, let’s consider an alternate age scenario: If two of the female members are older and one of the male members is also older, age could be a bridging characteristic that brings together people who might otherwise be divided across gender.

Conclusion

You will likely encounter many types of diversity in your professional life. You have learned that different people from different groups may encode and decode things in unexpected ways and that Canada’s history, geography, and demographic trends show that we are becoming increasingly diverse.

Differences between people can include religion and culture, generation, linguistic, gender, sexual orientation, and ability. While a diverse workforce can offer significant benefits to an organization, some communication challenges may arise, including the similarity-attraction phenomenon and the development of fault lines in teams.

Workplaces in Canada and around the world are making an effort to be more inclusive—that is, to create an open, supportive environment where staff are free to express themselves and work in a collaborative way. The flow of ideas from different cultures, generations, genders, and religious backgrounds is actively encouraged because of the resulting positive effects on business goals. These positive effects often take the form of desired attributes like increased innovation, productivity, employee happiness and retention, and other such metrics. This shift toward diversity and inclusivity is sometimes credited to the increase of millennials in the workplace and the qualities that this growing demographic look for in a professional environment.

Understanding how to communicate in a diverse environment is a key skill for a twenty-first-century employee.

Key Takeaways and Check In

Learning highlights

- In a social context, diversity is about embracing things that make us different and focusing on how these differences enrich our lives. Workplace diversity is not so different. It is about recognizing key factors of what makes us different. It is about making the most of the talents of people from diverse backgrounds to provide a more adaptable, effective, and productive workplace.

- Perceptual, cultural, and linguistic barriers can give rise to ineffective communication in the workplace and need to be overcome.

- Resistance to change (in practices), which includes intolerance to cultural diversity, can be a significant barrier to successful practices of diversity in the workplace.

- Recognition of the complexities as well as the benefits of diversity is a good first step to creating an inclusive workplace.

Further Reading, Links, and Attribution

- Check out this MTV video on understanding more about the debate between free speech and diversity-related political correctness.

- See this article on how to explain white privilege to a broke white person.

- This Atlantic article, “A person can’t be diverse,” discusses misuses of and problems with the term diversity from the perspective of filmmaker Ava DuVernay.

- View this article on five ways to foster a discrimination-free workplace.

References

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Business Case for Diversity. (n.d.). Ryerson University Diversity Institute. Retrieved from http://www.ryerson.ca/diversity/about/businesscase.html.

Button, S. B. (2001). Organizational efforts to affirm sexual diversity: a cross-level examination. Journal of Applied psychology, 86(1), 17.

Carlson, K. (2012). The true north LGBT: New Poll reveals landscape of gay Canada. National Post. http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/the-true-north-lgbt-new-poll-reveals-landscape-of-gay-canada.

Chatman, J. A., Polzer, J. T., Barsade, S. G., & Neale, M. A. (1998). Being different yet feeling similar: The influence of demographic composition and organizational culture on work processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 749–780.

Colella, A., & Varma, A. (2001). The impact of subordinate disability on leader-member exchange relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 304–315.

Culture. (n.d.) In OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/american_english/culture

Daniels, C. (2003, July 21). Women vs. Wal-Mart. Fortune, 148, 78–82.

Heilman, M. E., & Haynes, M. C. (2005). No credit where credit is due: attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 905.

Jehn, K. A., Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. (1999). Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 741–763.

Language Portal of Canada. (n.d.). Eliminating ethnic and racial stereotypes. Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.noslangues-ourlanguages.gc.ca/bien-well/fra-eng/style/ethnicracial-eng.html#.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392.

Pay Equity Commission. (2012). Government of Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.payequity.gov.on.ca/en/about/pubs/genderwage/wagegap.php.

Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict and performance. Administrative science quarterly, 44(1), 1–28.

Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P., & Evans, J. M. (2008). Unlocking the effects of gender faultlines on team creativity: Is activation the key? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 225.

Price, K. H., Harrison, D. A., & Gavin, J. H. (2006). Withholding inputs in team contexts: member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1375.

Sawyer, J. E., Houlette, M. A., & Yeagley, E. L. (2006). Decision performance and diversity structure: Comparing faultlines in convergent, crosscut, and racially homogeneous groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(1), 1–15.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Disability in Canada: Initial findings from the Canadian Survey on Disability. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2013002-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Low income cut-offs. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75f0002m/2012002/lico-sfr-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2015) Recent changes in demographic trends in Canada. Insights on Canadian Society. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2015001/article/14240-eng.htm#a6.

Statistics Canada. (2013) Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada. National Household Survey, 2011. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Portrait of Canada’s Labour Force. National Household Survey, 2011. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-012-x/99-012-x2011002-eng.pdf.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Persons in low income after tax. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/famil19a-eng.htm?sdi=low%20income.

Statistics Canada. (2011). Language Highlight Tables, 2011 Census. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/lang/Pages/highlight.cfm?TabID=1&Lang=E&Asc=0&PRCode=01&OrderBy=2&View=1&tableID=401&queryID=1&Age=1#TableSummary.

Terms and Concepts. (n.d.). In mygsa.ca. Retrieved from http://mygsa.ca/content/terms-concepts#.

Umphress, E. E., Simmons, A. L., Boswell, W. R., & Triana, M. D. C. (2008). Managing discrimination in selection: the influence of directives from an authority and social dominance orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 982.

White, E. (2008, June 30). Age is as age does: Making the generation gap work for you. Wall Street Journal, p. B6

W3Techs. (n.d.) Usage of Content Languages for Websites. Retrieved from http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/all

Attribution Statement (Communication and Diversity in Canadian Workplaces)

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

Chapter Content

- Original content contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

- The statistical information of Demographics in Canada was created by Laurent Martel of Statistics Canada for Insights on Canadian Society and published at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2015001/article/14240-eng.htm#a6. This materials is copyrighted and has been used in accordance with the Statistics Canada Open License Agreement.

- The statistical information presented from the National Household Survey, 2011 was published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.pdf. This materials is copyrighted and has been used in accordance with the Statistics Canada Open License Agreement.

- Content created by Anonymous for Understanding Sexual Orientation; in A Primer on Social Problems shared previously at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/a-primer-on-social-problems/s08-01-understanding-sexual-orientati.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Derivative work of content created by Anonymous for Managing Demographic and Cultural Diversity; in An Introduction to Organizational Behavior shared previously at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/an-introduction-to-organizational-behavior-v1.1/s06-managing-demographic-and-cultu.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Derivative work of content created by Anonymous for Language, Society, and Culture; in A Primer on Communication Studies shared previously at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/a-primer-on-communication-studies/s03-04-language-society-and-culture.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

Check Your Understandings

Original assessment items contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license