2 Procurement Strategy

Note. From Youngson, n.d. CC BY-SA 3.0

Learning Objectives

- Recognize key strategic sourcing principles and objectives.

- Understand portfolio analyses and their use in developing procurement strategies.

- Explain the commodity strategy development process and the key steps in that process.

- Apply the procurement of goods and services based on their relative strategic importance.

- Analyze the various procurement strategies used to achieve competitive advantage.

- Evaluate current and evolving strategies in the procurement field.

What do you know about the procurement strategy?

Strategic Sourcing

Strategic sourcing is a key component of the procurement function; it gives firms a competitive edge when it is linked to their overall goals and objectives. The concept of strategic sourcing and how it is developed, an overview of the importance of understanding materials, products, and services procured by corporations, and the relative importance of different components to those corporations are outlined in this chapter. Additionally, how procurement functions contribute to companies’ attaining their strategic goals is discussed, after which the various procurement and sourcing strategies that can be chosen to help ensure the support and achievement of corporate strategies are presented. The final part of this chapter includes evolving strategies that modern procurement groups adapt to remain competitive in their industries.

Strategic sourcing is defined as the process of determining long-term supply requirements, finding potential sources to fulfill those needs, selecting and approving suppliers to provide the services, negotiating PO agreements, and managing suppliers’ performance. Procurement functions support firms’ success by understanding organizational goals and objectives, analyzing and prioritizing sourcing alternatives, and developing effective sourcing strategies. By employing strategic sourcing processes, firms can be competitive as changes occur in markets, suppliers, global competition, new technologies, and risks. Remaining competitive requires procurement to contribute to the profitability of a firm, which can be done by concentrating on and developing world-class processes and suppliers, coordinating procurement activities related to organizations’ objectives, and identifying and managing risk. In order to achieve these advantages, procurement organizations need to adopt strategic sourcing processes. These processes encompass the entire supply network, its linkages, and how they impact procurement and purchasing decisions. The focus is on the top-tier supply network, value creation, risk, and uncertainty in the supply chain, as well as the overall responsiveness and resilience of the supply chain.

Procurement and Organizational Strategy

The organizational strategy contains long-term goals and objectives, including elements that restrict particular organizational current or desired activities and markets. Corporate strategies should contain specific plans of how firms will differentiate themselves from their competition, achieve long-term growth, manage costs, keep abreast of and respond to changes in the market, achieve customer satisfaction, remain profitable, and meet shareholders’ expectations. Procurement strategies must be linked to and support organizational strategy. Procurement is an essential element of organizations’ objectives, and by linking procurement and overall strategies, organizations can achieve competitiveness in procuring good-quality items at fair prices. In fact, procured goods and services typically provide a major area of opportunity to reduce costs and improve profitability.

The difference between goals and objectives is that goals are potential achievements that are to be reached, while objectives are the specific steps taken to reach those achievements. Developing strategic goals is a major part of developing strategy processes, including those for procurement; procurement thus works with senior management when developing these goals. The next step is translating these goals into concrete objectives. For example, if a company’s strategic goal is to reduce costs, then a key procurement goal could be to reduce purchased inventory. Then, an example of specific and measurable objectives for this goal would be to reduce purchased inventory by a certain percentage in the coming year.

According to Monczka et al. (2005), another key element in effective strategic sourcing is translating company-wide procurement goals and objectives into specific commodity-level goals and objectives. Essentially, this requires developing an appropriate procurement strategy for the products and services that companies purchase, depending on the relative importance of each product and service. These strategies are typically achieved using portfolio analysis, a comparison of the strategic goal, procurement goal, and the procurement objective.

- Strategic Company Goal

- Maximize return on investment

- Improve return on assets

- Improve product quality for end customers

- Reduce overall expense

- Concentrate on core competencies

- Procurement Goal

- Consolidate spending with fewer suppliers

- Reduce parts inventory supply

- Improve the quality of purchased materials

- Reduce expenses to optimize procurement

- Outsource non-core competency items to suppliers

- Procurement Objective

- Reduce supply base by 20% and establish price target reductions of at least 5%

- Optimize cycle and lead times to minimize stock levels on the ten most costly parts

- Implement Six Sigma total quality management (TQM) programs with the top five spend suppliers to achieve zero defects

- Analyze procurement process flows to improve productivity by 10%

- Work with manufacturing to establish a formal make vs. buy process to identify core and non-core items

Procurement Scorecard

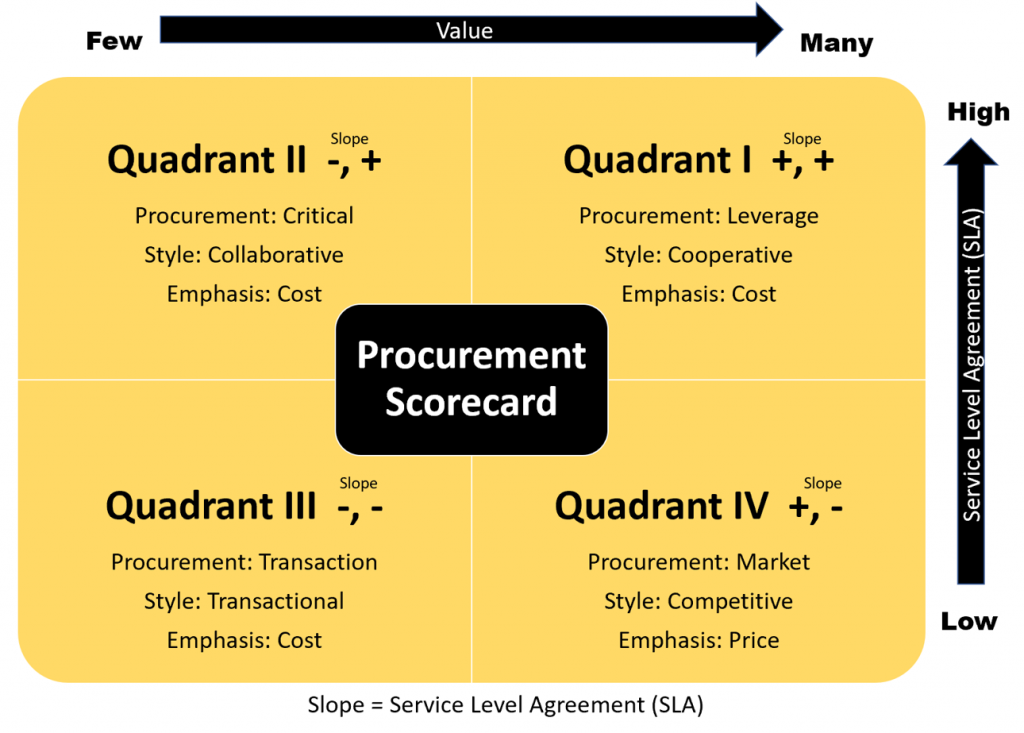

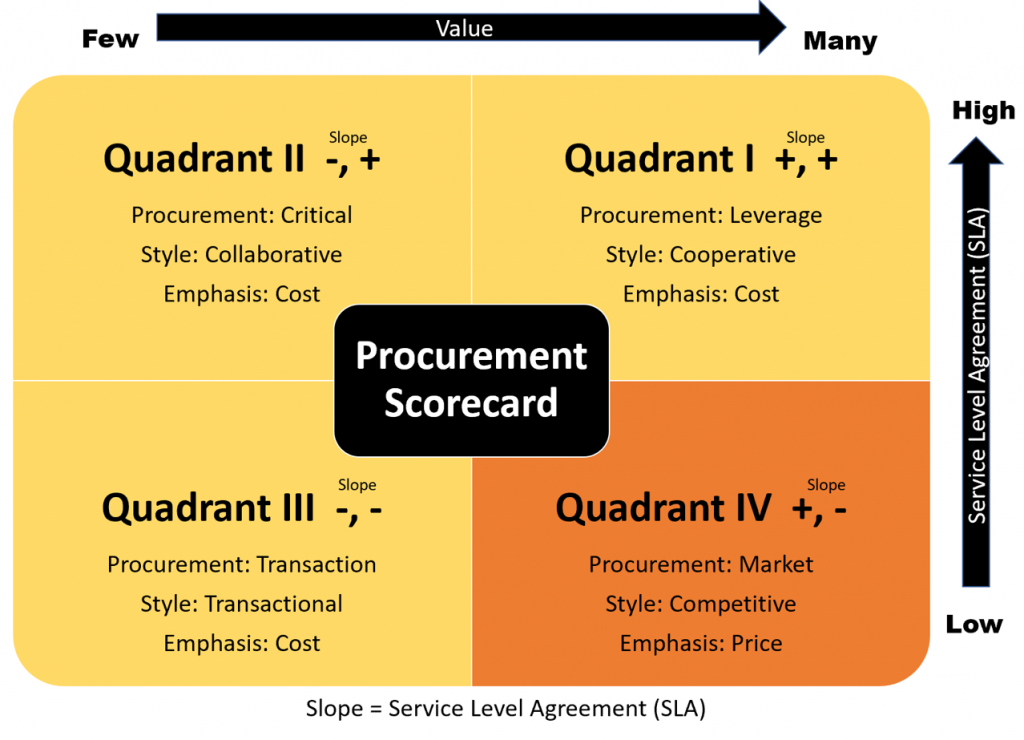

Figure 2.1

Procurement Scorecard

Note. From Snage. [Image Description]

Procurement Scorecard analysis involves classifying procured items and services into one of four categories, according to the relative cost and supply risk associated with each item. Each type of purchase is assigned to a quadrant that describes the supply strategy for the items and services classified within it. This supply segmentation indicates the need for different supply strategies for each quadrant of the procurement scorecard. Segmenting purchased items and services in this way makes it easier to decide which strategies and tactics should be applied in different supply markets and environments. Procurement personnel can clearly see how various items and services impact their firms’ competitiveness and profitability and can determine the appropriate operational strategy for handling each item from a procurement perspective.

A scorecard (see Figure 2.1, above) is a tool that supply managers must understand and employ. Presented in a 2×2 format, the matrix recognizes that an effective supply department must apply a variety, or portfolio, of strategies and approaches to different supply requirements. Users of this matrix segment their purchase requirements across two dimensions: the number of qualified suppliers in the marketplace and the value of specific goods or services to the buying organization. For some industry or organization requirements, qualified suppliers might consist of three to four suppliers or dozens of suppliers. In the matrix, value does not have a specific definition; it can be a function of total dollars spent on items or the perceived value of the item to the organization’s end customers and its ability to enhance the organization’s competitive position.

Perhaps the most important reason for using a scorecard is its prescriptive nature. For example, when supply managers or teams quantify the total spend for each commodity or category, goods or services can be positioned within the most appropriate quadrant. Classifying products and services in this way helps to identify the following: determining supplier relationships, participating in win-lose negotiations or win-win negotiations, taking a price-or cost-analytic approach, deciding on the best supply strategies and approaches, and creating value across different purchase requirements.

As a more detailed example, personnel from an IT company used portfolio analysis to determine what they believed were the best sourcing strategies for their various needs. An IT help desk might be determined as less specialized, or core, to the business and therefore placed in the transaction quadrant, while other functions, such as Java 2 Platform and Enterprise Edition (J2EE) development might be determined to be more critical and thus placed in the critical quadrant. The quadrants into which specific requirements are categorized in the portfolio analysis help determine how work should be sourced, as well as the degree of information search and risk management that should take place. The following sections briefly describe each quadrant within the scorecard and outline the development of different types of sourcing strategies for the items categorized in each quadrant.

Quadrant I, Leverage

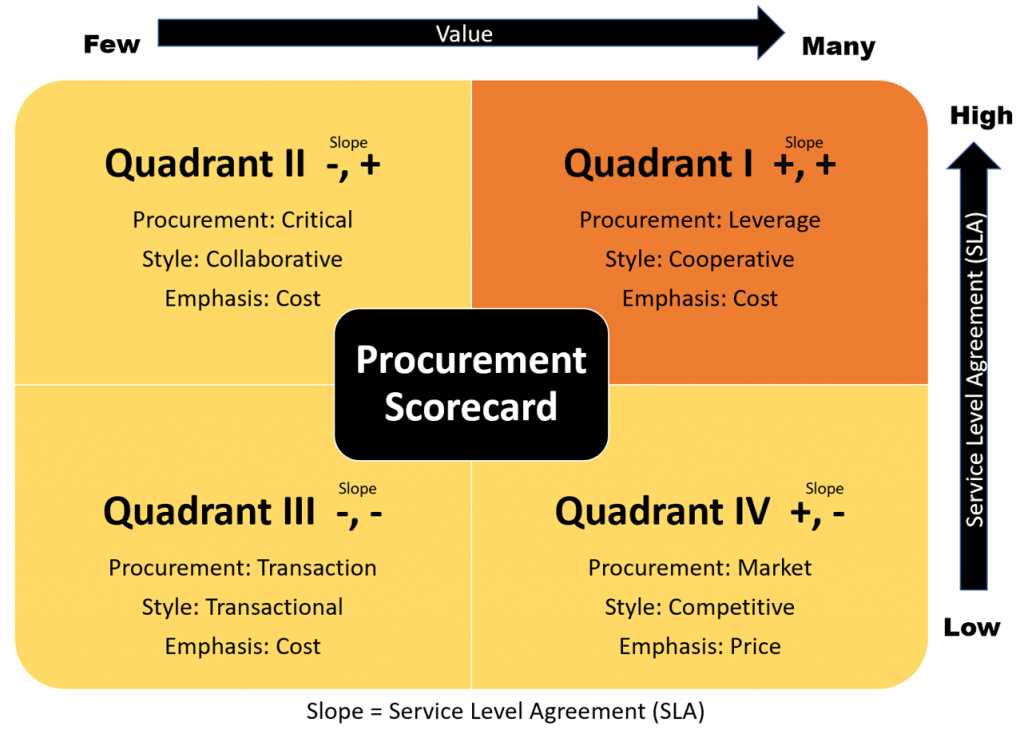

Figure 2.2

Quadrant I, Leverage

Note. From Snage. [Image Description]

On the upper right is the leverage quadrant, which includes items that should lead to a range of benefits after consolidating purchase volumes and reducing the size of the supply base. Leverage items include any grouping or family of items in which volumes can be combined company-wide for economic advantages, such as bulk chemicals and standard semi-finished products. Because leverage items are often candidates for long-term agreements, supply managers should engage in intense information searches regarding them. Developing long-term contracts should lead to questions about cost, quality, delivery, packaging, logistics, inventory management, financial health, and after-sales service. Although this quadrant does not have the most suppliers in terms of numbers, the dollar value of the leverage items should be high. It is common to have suppliers in this quadrant receive 80% or more of total purchase dollars, with leverage often employed.

Quadrant II, Critical

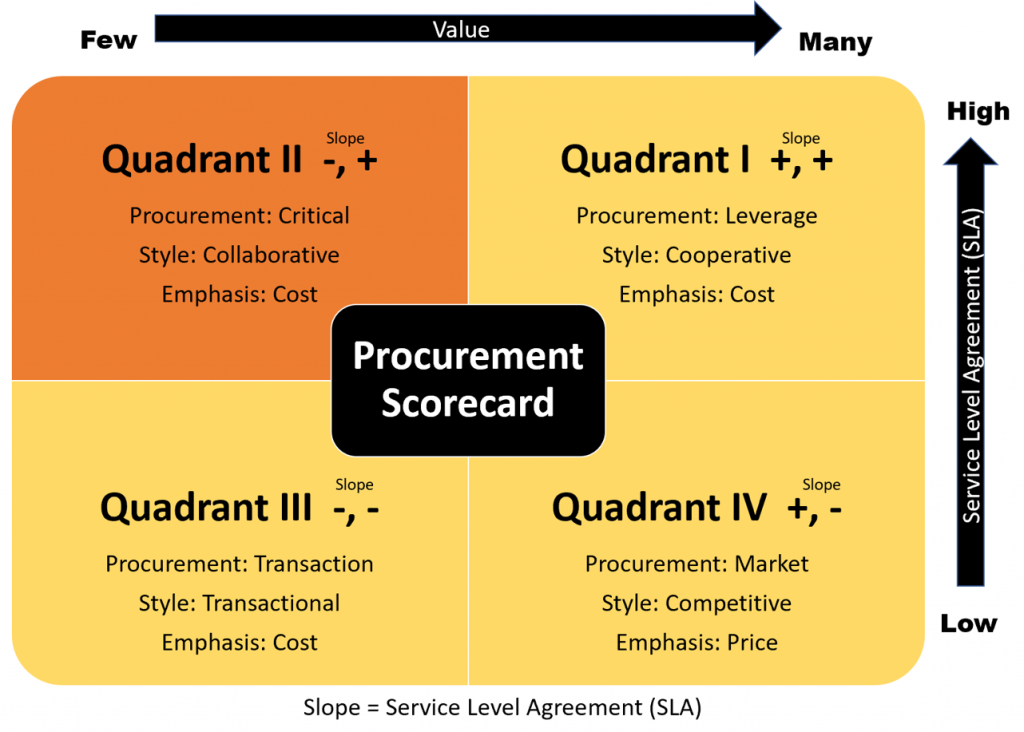

Figure 2.3

Quadrant II, Critical

Note. From Snage.[Image Description]

The upper left quadrant is the critical quadrant, which includes goods and services with the following characteristics: they consume a large portion of the total purchase dollars; they are essential to service or product functions, or they involve areas where end customers value the differentiation offered by goods and services. This quadrant typically has fewer suppliers that satisfy purchaser requirements and often involve customization rather than standardization. At times, suppliers are critical because they have patent rights to goods or services that the buying company simply must acquire. Products that fall into this quadrant include specially engineered items like aircraft engines and complex medical equipment.

Quadrant III, Transaction

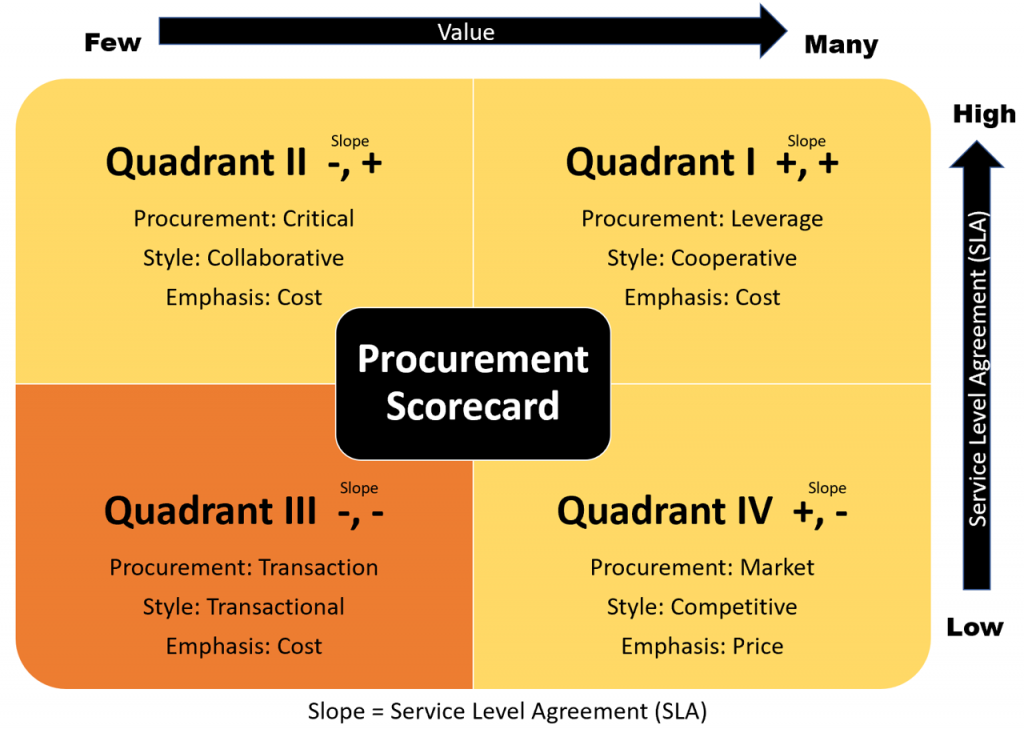

Figure 2.4

Quadrant III, Transaction

Note. From Snage. [Image Description]

The goods and services in the transaction quadrant at the lower-left have a lower total value with a limited supply market. Although many suppliers might be available to provide these items, the cost of a supplier search almost always outweighs the value of the search, because when the supply market is limited, the low cost of goods outweighs the value of the search of suppliers, even though there may not be many suppliers. Therefore, the supply market is actually limited. Items usually assigned to the transaction quadrant include miscellaneous office supplies, one-time purchases, magazine subscriptions to trade journals, and emergency tools needed at remote locations. The main way for supply professionals to create value in this quadrant is by reducing the transaction cost of purchasing these items, which is usually achieved through electronic systems or procurement cards; however, the items in the transaction quadrant are of minimal concern in terms of supply risk.

Quadrant IV, Market

Figure 2.5

Quadrant IV, Market

Note. From Snage. [Image Description]

On the lower right is the market quadrant, which includes standard items and services that have the following characteristics: they are involved in an active supply market; they have low to medium total value; they have many suppliers that can provide substitute products and services with low supplier switching costs, and they feature well-defined specifications. Goods that are often categorized in this quadrant here include commodity items like fasteners, corrugated packaging, and other basic, raw materials that do not have an especially high dollar value. Market quadrant items are often sourced globally because they are easy to specify, many supply alternatives are available, and supply managers do not look much past cost, quality, and delivery.

Strategic Sourcing Process, 7 Steps

This section covers the commodity strategy development process. It is crucial for companies to follow a structured process in developing commodity strategies to help ensure that it is carried out in an effective and efficient manner. The following steps should be completed by procurement personnel when procuring goods and services that are of relative strategic importance to companies’ success in the marketplace. The exact products and services that are to be subjected to this strategic sourcing process are determined through portfolio analysis. Each of the steps needs to be completed in the order indicated to help ensure that commodity strategies are developed and executed well.

Step 1 of 7, Define Business Requirements Using Commodity Strategies

The business unit strategy is the driving force of procurement strategies for the products and services procured by business units within firms. These strategies are translated into purchasing goals, from which strategies are developed for commodity families. Commodities are general categories, or families of, procured items, such as fuel, office supplies, wood, and cotton. Developing procurement strategies is often carried out by commodity teams that are led by procurement professionals dedicated to procuring specific commodities or groups of commodities. Commodity teams are often formed from employees across businesses, all of whom are familiar with the commodity being procured. The commodity team is responsible for developing the commodity strategies that define the details and the action plans for managing commodities.

Step 2 of 7, Define the Strategic Importance of the Product or Service Procured

The next step in the sourcing strategy is understanding the relative importance to the business unit objectives of the product or service procured, which is typically achieved using portfolio analysis, as previously noted. A portfolio analysis typically includes supply market risks and focuses on the value-generating capability of purchase in light of the risks of making that purchase in the marketplace. From this analysis, the goods and services purchased by organizations can be placed in the appropriate quadrant, broad procurement strategies can be developed by quadrant, specific commodity strategies can be developed for each commodity within a quadrant, and decisions can then be made about the most appropriate sourcing strategy for each category.

Step 3 of 7, Determine Business and Procurement Requirements, Spend, and Conduct a Market Analysis

This stage requires a spend analysis, which entails identifying the products and services that each business unit—marketing, production, engineering, warehousing, etc.—is buying. It is important to understand where money is being spent and with which suppliers. This spends analysis can reveal different that business units are paying different prices for the same items. It can also reveal where it is possible to consolidate spending for various items with fewer suppliers or where excessive variety exists. Then, market analysis should be conducted. This identifies the important characteristics of supply markets and business unit requirements. The results of this analysis provide a sound basis for decision-making. The information for this research can come from the Internet, supplier literature, government reports, professional associations, trade magazines, and database research.

The main steps carried out in spend and market analyses are:

- Identify past expenditures by commodity and supplier

- Determine total expenditure for commodities or services as a percentage of the total for the business unit

- Identify current suppliers and potential suppliers by commodity

- Determine the marketplace pricing for commodities and services

- Determine trends in pricing

- Carry out supplier analyses by completing supplier scorecards and other forms of assessment

- Investigate strategies of market leaders to identify best practices

- Determine current and future volume requirements that could be held by the organization

- Identify opportunities for future spend and market analyses

Step 4 of 7, Set Goals and Conduct a Gap Analysis

The next step in strategic sourcing is establishing specific targets for evaluating progress against goals. Goals should relate directly to the objectives and requirements of businesses and business units. Effective goals, which are established with stakeholders, should be measurable and action-oriented, evaluate internal progress over time, and compare performance to external benchmarks and competition. They should also go beyond price to be based on total costs. Goals should also be based on competitive analyses, comparisons with market leaders, and future trends. An integral part of this process is the gap analysis, which is carried out to determine firms’ current standings in terms of their competition. Gap analyses help business managers understand and quantify the gaps that exist between their current status and the ideal state of their businesses.

Step 5 of 7, Develop Sourcing Strategies and Objectives

In this step, sourcing strategies are developed from the information obtained and the analyses carried out in the previous steps. Sourcing strategies should include the following elements:

- Recommended suppliers, locations, and relative sizes (e.g., local, regional, or global suppliers).

- The number of suppliers and the amount of business to be awarded to suppliers.

- Lengths and types of contracts.

- Product design requirements and extent of supplier involvement in product and service designs.

- Supplier development, relationship management requirements, and activities.

- Overall sourcing volume mix by suppliers and products, services, or commodity groups.

Step 6 of 7, Carry Out the Strategy

In this step, procurement professionals carry out their sourcing strategies. Key elements of strategy execution include the following:

- Documenting and communicating the strategy to everyone involved, including owners, stakeholders, customers, and suppliers.

- Establishing tasks to be completed and timelines for completion.

- Assigning accountability for executing the strategy.

- Ensuring adequate resources are made available.

- Developing contingency plans.

Various individuals within the procurement group, working in cross-functional teams, would typically be tasked with the responsibility for implementing the strategy and carrying out the plans.

Step 7 of 7, Monitor Results and Review Performance

The final step is to ensure that the strategy is achieving its desired objectives. Regular reviews must be conducted to determine if the strategy is achieving its objectives and to determine if a modification of the strategy is required. It is important to remember that strategy outcomes may vary considerably, depending on the specific commodities and supply markets involved.

These key steps are carried out by procurement management and must be included in monitoring and reviewing performance:

- Conduct regular review meetings to determine if the strategy is achieving the desired results

- Share results with stakeholders

- Assess internal and external stakeholder perceptions

- Ensure objectives and goals that are outlined in the strategy are met, adjusting it if necessary

- Provide feedback on actions taken

Types of Sourcing Strategies and Tactics

Organizations use a variety of procurement strategies and tactics to achieve a competitive advantage, including supply base rationalization, total quality management efforts with key suppliers, global sourcing, long-term supplier relationships and supplier development, early supplier involvement in the design, and electronic procurement (e-procurement). This section briefly reviews some of the key strategies that are used in many of these organizations.

Supply Base Rationalization

The supply base comprises all suppliers that organizations utilize to procure their goods and services. Rationalizing the supply base is primarily aimed at determining the appropriate number and mix of suppliers for all organizations. This process is ongoing as organizations’ needs change over time, and it involves analyzing the number of suppliers required for current and future needs of purchased items and/or services. Supply base rationalization focuses on developing the best blend of suppliers, given organizations’ requirements. The intention is to identify the best values and the appropriate number of suppliers for all commodities, based on overall business strategies.

Total Quality Management (TQM) with Suppliers

Total Quality Management (TQM) is a management system that involves all employees in ongoing quality improvement efforts. TQM with suppliers involves the procurement departments working with key suppliers to initiate a quality improvement program. This program requires working with suppliers to establish standards of performance, to measure performance, and to even support the supplier by assisting them with training for their organization in quality improvement tools and techniques. This is especially true when companies reduce the total number of their suppliers, frequently in conjunction with TQM programs or Just-In-Time productions and inventory systems. Just-In-Time is a method of supply using a strategy of shipping in smaller, more frequent lots with deliveries that arrive as they are needed rather than stockpiling materials or parts. It is also important to note that subpar quality from a supplier can have an adverse impact on the manufacturing and production processes.

Essentially, procurement professionals recognize that quality management requires quality materials and parts. That is, the final product is only as good as the parts used in the process, and procurement is vital in helping suppliers ensure the quality of parts that create final products. Procurement accomplishes its role by visiting sites to assess supplier quality and helping suppliers implement a quality improvement program for improving the quality of their supplied products and services.

Sourcing Globally

Many firms engage in global sourcing; however, long distances make planning and logistics more difficult, currency fluctuations can change the economics of a transaction, different business cultures and languages can lead to misunderstandings, and the paperwork with international transactions can be cumbersome. Nonetheless, for most procurement managers global sourcing is about price. Other motivators include gaining access to new sources of technology and higher quality as well as introducing competition to the domestic supply base. Price reduction is a key motivator behind outsourcing globally. Potential price savings opportunities can be realized by sourcing globally by taking advantage of significantly lower labour costs in certain countries. There is also the risk of hidden costs, particularly for less-experienced organizations. These costs are due to extended supply chains and include costs of anticipating and managing increased risks and increased inventories.

Another reason companies procure globally is that some commodities are only available from certain regions, which makes worldwide sourcing a necessity when those items are required. Also, the supply base to support certain industries, particularly in the United States (U.S.) and Europe, might be gone or severely depleted. For example, many companies that manufacture electronic components and contract manufacturers of other products, such as clothing, might be entirely relocated to Asia from South America. Firms can have their unique reasons for sourcing globally, which can differ among firms (e.g., requiring a certain brand’s product that is only provided by one supplier in another country).

Long-Term Supplier Relationships and Supplier Development

Long-term supplier relationships involve working with key suppliers to reduce costs and improve service levels overall. In some cases, procurement may find that suppliers’ capabilities do not match current or future expectations, but the department may wish to develop the supplier because it has the potential to perform well. In this case, procurement will work with such suppliers to facilitate improvement. It was discussed how the sourcing strategy uses a smaller number of suppliers, which frequently leads to an alliance or partnership with suppliers to assure an adequate supply of quality materials over time and at an optimum total acquired cost. This partnership concept encompasses more than the procurement process; it also includes different areas and industries throughout supply chains. For example, partnerships can evolve with transportation companies, contract logistics companies (i.e., third-party providers), and other channel members.

Early Supplier Involvement in Design

Early involvement of suppliers in design is the process of working with suppliers early during the design and development of current or new products that companies want to purchase. Supplier involvement may be informal or formal, depending on the nature of the products or services procured and the desired nature of the relationship with given suppliers. It is beneficial to involve suppliers early in the design phase to enlist supplier’s ideas and to ensure that products can be manufactured in accordance with the engineering specifications as it becomes increasingly difficult and costly to make design changes after designs have been fully developed. The cost impact of design changes will increase substantially in the later phases of the design process. Additionally, design modifications become less flexible and more costly to achieve during the latter phases of design completion.

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is a calculation designed to help procurement personnel make more informed financial decisions when purchasing products or services. It is also one of the most important concepts in purchasing and supply management. Rather than simply identifying the purchase price of items, TCO adds to the initial purchase price other costs expected to be incurred during the life of the product (e.g., service, repair, and insurance). In addition to price, TCO considers total costs of acquisition use and administration, maintenance, and disposal of given items or services. TCO analysis involves determining all costs related to the procurement of given products or services to allow for a number of needs: accurate estimation of true costs, cost comparison purposes, and supplier negotiation.

Electronic Procurement (E-Procurement)

E-procurement is a way of using Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems and the Internet to allow businesses to purchase goods and services in an easier, faster, and less-expensive way. The overall goal is to streamline the purchasing process so businesses can focus more management time on earning revenue and serving customers. With e-procurement, purchases are easier to track because they are completed using ERP systems and the Internet, and the company’s managers can easily see who made which purchases without waiting to receive a monthly revolving credit statement. Furthermore, many companies incorporate product specifications into their e-procurement systems. Buyers also save time by not needing to leave their desks or make phone calls to suppliers to place orders.

Suppliers receive orders almost immediately, so they can fulfill and ship them much faster than with the traditional procurement methods. Using the ERP systems and Internet for procurement also makes it possible to research information about suppliers and to compare product and service offerings. Various software applications can be used for e-procurement. According to EPIQ (2014), e-procurement applications provide tools that let businesses organize and compare supplier information more effectively.

Integrating Marketing and Sourcing

A number of evolving sourcing strategies and several best practices exist in the procurement of goods and services. In certain firms, sourcing managers may be integrated with marketing. Examples of areas in which marketing teams require procurement’s support include sourcing printing services, conventions, meetings, promotional displays and trade shows, marketing research services, and advertising and promotion. Integrating sourcing managers with marketing helps promote a closer and better understanding of marketing-related sourcing requirements and how these requirements can best be fulfilled. Sourcing involvement, for example, may result in reducing the number of company-wide printing suppliers from 600 to 500.

Co-Locating Procurement Individuals with Internal Functions

In many firms, the procurement function is co-located and works closely with other internal supply chain functions, such as transportation, warehousing, and production. Co-location occurs when procurement individuals are physically situated in close proximity with supply chain professionals in organizations. Working in similar spaces helps to ensure, for example, that sourcing has early insight into new products that might affect the development of strategic sourcing plans. The direct involvement of sourcing with other supply chain team members is a best practice at many successful firms.

Key Takeaways

Procurement plays a significant role in formulating strategies for firms as a whole and with regard to individual items and services. This department also uses a commodity strategy development process and follows a number of key steps in that process. Additionally, procurement develops a strategy for, and efforts connected to, the procurement of goods and services based on the relative strategic importance of those goods and services. Organizations use a variety of procurement strategies to achieve a competitive advantage. Lastly, there are a number of current and evolving strategies in the procurement field.

Review Questions

References

EPIQ. (2014). Electronic procurement. https://www.epiqtech.com/E-Procurement-Systems.htm

Monczka, D., Trent, R., & Handfield, R. (2005). Purchasing and supply chain management (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Youngson, N. (n.d.) Strategy [Photograph]. Alpha Stock Photography. http://alphastockimages.com/photo/706/Strategy.html

Creative Commons Attribution

This chapter contains material adapted from Supply Management and Procurement Certification Track. LINCS in Supply Chain Management Consortium. March 2017. Version: v2.26. www.LINCSeducation.org.

Image Descriptions:

Figure 2.1: This figure is a Procurement Scorecard which is a tool that supply managers must understand and employ. The scorecard is made up of four quadrants and two axes. Across the top from left to right is the value axis (few on the left and many on the right). On the right side from bottom to top is the service level agreement axis or SLA (low SLA at the bottom right to high SLA at the top right). There are four quadrants. The first quadrant (top right) reads Quadrant I Procurement: Leverage, Style: Cooperative, Emphasis: Cost. The second quadrant (top left) reads Quadrant I Procurement: Critical, Style: Collaborative, Emphasis: Cost. The third quadrant (bottom left) reads Procurement: Transaction, Style: Transactional, Emphasis: Cost. The fourth quadrant (bottom right) reads Quadrant IV Procurement: Market, Style: Comprehensive, Emphasis: Price. Users of this matrix segment their purchase requirements across two dimensions: the number of qualified suppliers in the marketplace and the value of specific goods or services to the buying organization. [Back to Image]

Figure 2.2: This figure highlights Quadrant I (top right) which reads Quadrant I Procurement: Leverage, Style: Cooperative, Emphasis: Cost. This quadrant includes items that should lead to a range of benefits after consolidating purchase volumes and reducing the size of the supply base. [Back to Image]

Figure 2.3: This figure highlights Quadrant II (top left) which reads Quadrant II Procurement: Leverage, Style: Collaborative, Emphasis: Cost. This quadrant typically has fewer suppliers that satisfy purchaser requirements and often involve customization rather than standardization. [Back to Image]

Figure 2.4: This figure highlights Quadrant III (bottom left) which reads Quadrant III Procurement: Transaction, Style: Transactional, Emphasis: Cost. The goods and services in the transaction quadrant at the lower-left have a lower total value with a limited supply market. [Back to Image]

Figure 2.5: This figure highlights Quadrant IV (bottom right) reads Quadrant IV Procurement: Market, Style: Comprehensive, Emphasis: Price. Goods that are often categorized in this quadrant here include commodity items like fasteners, corrugated packaging, and other basic, raw materials that do not have an especially high dollar value. [Back to Image]