13.2 Customer Relationships and Selling Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Understand the types of selling relationships that firms seek.

- Be able to select the selling strategy needed to achieve the desired customer relationship.

Customer Relationships

Some buyers and sellers are more interested than others in building strong relationships with each other. Generally speaking, however, all marketers are interested in developing stronger relationships with large customers. Why? Because serving one large customer can often be more profitable than serving several smaller customers, even when the large customer receives quantity discounts. Serving many small customers—calling on them, processing all their orders, and dealing with any complaints—is time consuming and costs money. To illustrate, consider the delivery process. Delivering a large load to one customer can be accomplished in just one trip. By contrast, delivering smaller loads to numerous customers will require many more trips. Marketers, therefore, want bigger, more profitable customers. Big box retailers such as Home Depot and Best Buy are examples of large customers that companies want to sell to because they expect to make more profit from the bigger sales they can make.

Marketers also want stronger relationships with customers who are innovative, such as lead users. Similarly, marketers seek out customers with status or who are recognized by others for having expertise. For example, Holt Caterpillar is a Caterpillar construction equipment dealer in Texas and is recognized among Caterpillar dealers for its innovativeness. Customers such as Holt influence others (recall that we discussed these opinion leaders in Chapter 3 “Consumer Behavior: How People Make Buying Decisions”). When Holt buys or tries something new and it works, other Cat dealers are quick to follow. Some companies are reaching out to opinion leaders in an attempt to create stronger relationships. For example, JCPenney uses e-mail and Web sites to form relationships with opinion leaders who will promote its products. We’ll discuss how the company does so in the next chapter.

Salespeople are also tasked with maintaining relationships with market influencers who are not their customers. As mentioned earlier, Mary Gros at Teradata works with professors and with consultants so that they know all about Teradata’s data warehousing solutions. Professors who teach data warehousing influence future decision makers, whereas consultants and market analysts influence today’s decision makers. Thus, Gros needs to maintain relationships with both groups.

Types of Sales Relationships

Think about the relationships you have with your friends and family. Most relationships operate along a continuum of intimacy or trust. The more you trust a certain friend or family member, the more you share intimate information with the person, and the stronger your relationship is. The relationships between salespeople and customers are similar to those you have, which range from acquaintance to best friend (see Figure 13.2 “The Relationship Continuum”).

As this figure depicts, business relationships range from transactional, or one-time purchases, to strategic partnerships that are often likened to a marriage. Somewhere in between are functional and affiliative relationships that may look like friendships.

At one end of the spectrum are transactional relationships; each sale is a separate exchange, and the two parties to it have little or no interest in maintaining an ongoing relationship. For example, when you fill up your car with gas, you might not care if it’s gas from Exxon, Shell, or another company. You just want the best price. If one of these companies went out of business, you would simply do business with another.

Functional relationships are limited, ongoing relationships that develop when a buyer continues to purchase a product from a seller out of habit, as long as her needs are met. If there’s a gas station near your house that has good prices, you might frequently fill up there, so you don’t have to shop around. If this gas station goes out of business, you will be more likely to feel inconvenienced. MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) items, such as such as nuts and bolts used to repair manufacturing equipment are often sold on the basis of functional relationships. There are small price, quality, and services differences associated with the products. By sticking with the product that works, the buyer reduces his costs.

Affiliative selling relationships are more likely to occur when the buyer needs a significant amount of expertise needed from the seller and trust is an issue. Ted Schulte describes one segment of his market as affiliative; the people in this segment trust Schulte’s judgment because they rely on him to help them make good decisions on behalf of patients. They know that Schulte wouldn’t do anything to jeopardize that relationship.

A strategic partnership is one in which both the buyer and seller commit time and money to expand “the pie” for both parties. This level of commitment is often likened to a marriage. For example, GE manufactures the engines that Boeing uses in the commercial planes it makes. Both companies work together to advance the state of engine technology because it gives them both an edge. Every time Boeing sells an airplane, GE sells one or more engines. A more fuel-efficient or faster engine can mean more sales for Boeing as well as GE. As a result, the engineers and other personnel from both companies work very closely in an ongoing relationship.

Going back to the value equation, in a transactional relationship, the buyer calculates the value gained after every transaction. As the relationship strengthens, value calculations become less transaction-oriented and are made less frequently. There will be times when either the buyer or the seller engages in actions that are not related directly to the sale but that make the relationship stronger. For example, a GE engineer may spend time with Boeing engineers simply educating them on a new technology. No specific sale may be influenced, but the relationship is made stronger by delivering more value.

Note that these types of relationships are not a process—not every relationship starts at the transactional level and moves through functional and affiliative to strategic. Nor is it the goal to make every relationship a strategic partnership. From the seller’s perspective, the motivation to relate is a function of an account’s size, innovation, status, and total lifetime value.

Selling Strategies

A salesperson’s selling strategies will differ, depending on the type of relationship the buyer and seller either have or want to move toward. There are essentially four selling strategies: script-based selling, needs-satisfaction selling, consultative selling, and strategic partnering.

Script-Based Selling

Salespeople memorize and deliver sales pitches verbatim when they utilize a script-based selling strategy. Script-based selling is also called canned selling. The term “canned” comes from the fact that the sales pitch is standardized, or “straight out of a can.” Back in the late 1880s, companies began to use professional salespeople to distribute their products. Companies like National Cash Register (NCR) realized that some salespeople were far more effective than others, so they brought those salespeople into the head office and had them give their sales pitches. A stenographer wrote each pitch down, and then NCR’s sales executives combined the pitches into one effective script. In 1894, the company started one of the world’s first sales schools, which taught people to sell using the types of scripts developed by NCR.

“National Cash Register” by DevonshireMedia, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Script-based selling works well when the needs of customers don’t vary much. Even if they do, a script can provide a salesperson with a polished and professional description of how an offering meets each of their needs. The salesperson will ask the customer a few questions to uncover his or her need, and then provides the details that meet it as spelled out in the script. Scripts also ensure that the salesperson includes all the important details about a product.

Needs-Satisfaction Selling

The process of asking questions to identify a buyer’s problems and needs and then tailoring a sales pitch to satisfy those needs is called needs-satisfaction selling. This form of selling works best if the needs of customers vary, but the products being offered are fairly standard. The salesperson asks questions to understand the needs then presents a solution. The method was popularized by Neil Rackham, who developed the SPIN selling approach. SPIN stands for situation questions, problem questions, implications, and needs-payoff, four types of questions that are designed to fully understand how a problem is creating a need. For example, you might wander onto a car lot with a set of needs for a new vehicle. Someone else might purchase the same vehicle but for an entirely different set of reasons. Perhaps this person is more interested in the miles per gallon, or how big a trailer the vehicle can tow, whereas you are more interested in the vehicle’s style and the amount of legroom and headroom it has. The effective salesperson would ask you a few questions, determine what your needs are, and then offer you the right vehicle, emphasizing those points that meet your needs best. The vehicle’s miles per gallon and towing capacity wouldn’t be mentioned in a conversation with you because your needs are about style and room.

Consultative Selling

To many students, needs-satisfaction selling and consultative selling seem the same. The key difference between the two is the degree to which a customized solution can be created. With consultative selling, the seller uses special expertise to solve a complex problem in order to create a somewhat customized solution. For example, Schneider-TAC is a company that creates customized solutions to make office and industrial buildings more energy efficient. Schneider-TAC salespeople work with their customers over the course of a year or longer, as well as with engineers and other technical experts, to produce a solution.

Strategic-Partner Selling

When the quality of the relationship between the buyer and seller moves toward a strategic partnership, the selling strategy gets more involved than even consultative selling. In strategic-partner selling, both parties invest resources and share their expertise with each other to create solutions that jointly grow one another’s businesses. Schulte, for example, positions himself as a strategic partner to the cardiologists he works with. He tries to become a trusted partner in the patient care process.

Choosing the Right Sales Strategy for the Relationship Type and Selling Stage

The sales-strategy types and relationship types we discussed don’t always perfectly match up as we have described them. Different strategies might be more appropriate at different times. For example, although script-based selling is generally used in transactional sales relationships, it can be used in other types of sales relationships as well, such as affiliative-selling relationships. An affiliative-sales position may still, for example, need to demonstrate new products, a task for which a script is useful. Likewise, the same questioning techniques used in needs-satisfaction selling might be used in relationships characterized by consultative selling and strategic-partner selling.

So when is each method more appropriate? Again, it depends on how the buyer wants to buy and what information the buyer needs to make a good decision.

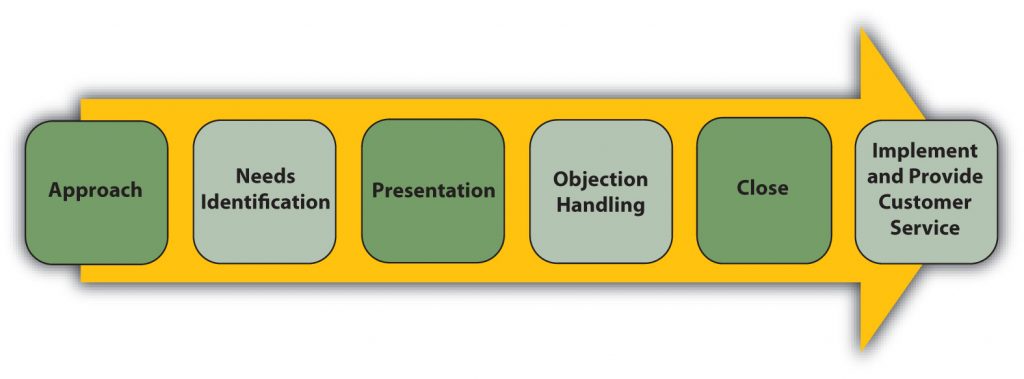

The typical sales process involves several stages, beginning with the preapproach and ending with customer service. In between are other stages, such as the needs-identification stage (where you would ask SPIN questions), presentation stage, and closing stage (see Figure 13.4 “The Typical Sales Process”).

The preapproach is the planning stage. During this stage, a salesperson may use LinkedIn to find the right person to call and to learn about that person. In addition, a Google search may be performed to find the latest news on the company, while a search of financial databases, such as Standard & Poor’s, can provide additional news and information. A salesperson may also search internal data in order to determine if the potential buyer has any history with the company. Note that such extensive precall planning doesn’t always happen; sometimes a salesperson is literally just driving by, sees a potential customer, and decides to stop in, but in today’s information age, a lot of precall planning can be accomplished through judicious use of Web-based resources.

In the approach, the salesperson attempts to capture enough of the prospective customer’s attention and interest in order to continue the sales call. If it is a first-time call, introductions are needed. A benefit that could apply to just about any customer may also be offered to show that the time will be worthwhile. In this stage, the salesperson is attempting to convince the buyer to spend time exploring the possibility of a purchase.

A typical sales process starts with the preapproach and move through several stages to the close. Good salespeople continue with making sure the customer gets the product, uses it right, and is happy with it.

With the buyer’s permission, the salesperson then moves into a needs identification section. In complex situations, many questions are asked, perhaps over several sales calls. These questions will follow the SPIN outline or something similar. Highly complex situations may require that questions be asked of many people in the buying organization. In simpler situations, needs may not vary across customers so a canned presentation is more likely. Then, instead of identifying needs, needs are simply listed as solutions are described.

A presentation is then made that shows how the offering satisfies the needs identified earlier. One approach to presenting solutions uses statements called FEBAs. FEBA stands for feature, evidence, benefit, and agreement. The salesperson says something like, “This camera has an automatic zoom [Feature]. If you look at the viewfinder as I move the camera, you can see how the camera zooms in and out on the objects it sees [Evidence]. This zoom will help you capture those key moments in Junior’s basketball games that you were telling me you wanted to photograph [Benefit]. Won’t that add a lot to your scrapbooks [Agreement]?”

Note that the benefit was tied to something the customer said was important. A benefit only exists when something is satisfying a need. The automatic zoom would provide no benefit if the customer didn’t want to take pictures of objects both near and far.

Objections are concerns or reasons not to continue that are raised by the buyer, and can occur at any time. A prospect may object in the approach, saying there isn’t enough time available for a sales call or nothing is needed right now. Or, during the presentation, a buyer may not like a particular feature. For example, the buyer might find that the automatic zoom leads the camera to focus on the wrong object. Salespeople should probe to find out if the objection represents a misunderstanding or a hidden need. Further explanation may resolve the buyer’s concern or there may need to be a trade-off; yes, a better zoom is available but it may be out of the buyer’s price range, for example.

When all the objections are resolved to the buyer’s satisfaction, the salesperson should ask for the sale. Asking for the sale is called the close, or a request for a decision or commitment from the buyer. In complex selling situations that require many sales calls, the close may be a request for the next meeting or some other action. When the close involves an actual sale, the next step is to deliver the goods and make sure the customer is happy.

There are different types of closes. Some of these include:

- Direct request: “Would you like to order now?”

- Minor point: “Would you prefer red or blue?” or “Would you like to view a demonstration on Monday or Tuesday?”

- Summary: “You said you liked the colour and the style. Is there anything else you’d like to consider before we complete the paperwork?”

When done properly, closing is a natural part of the process and a natural part of the conversation. But if pushed inappropriately, buyers can feel manipulated or trapped and may not buy even if the decision would be a good one.

The sales process used to sell products is generally the same regardless of the selling strategy used. However, the stage being emphasized will affect the strategy selected in the first place. For example, if the problem is a new one that requires a customized solution, the salesperson and buyer are likely to spend more time in the needs identification stage. Consequently, a needs-satisfaction strategy or consultation strategy is likely to be used. Conversely, if it’s already clear what the client’s needs are, the presentation stage is likely to be more important. In this case, the salesperson might use a script-based selling strategy, which focuses on presenting a product’s benefits rather than questioning the customer.

Let’s review some of the content of this chapter. Watch the video below, answer a short question and then check whether you can correctly order the elements of a sales call.

Key Takeaways

Some buyers and sellers are more interested in building strong relationships with one another than others. The four types of relationships between buyers and sellers are transactional, functional, affiliative, and strategic. The four basic sales strategies salespeople use are script-based selling, needs-satisfaction selling, consultative selling, and strategic-partner selling. Different strategies can be used with in different types of relationships. For example, the same questioning techniques used in needs-satisfaction selling might be used in relationships characterized by consultative selling and strategic-partner selling. The sales process used to sell products is generally the same regardless of the selling strategy used. However, the strategy chosen will depend on the stage the seller is focusing on. For example, if the problem is a new one that requires a customized solution, the salesperson and buyer are likely to spend more time in the needs identification stage. Consequently, a needs-satisfaction strategy or consultation strategy is likely to be used.

Review Questions

- Do customer relationships begin as transactional and move toward strategic partnerships?

- How does each sales strategy vary?

- Which step of the sales process is most important and why? How would the steps of the sales process vary for each type of sales position?