Topic 4: Enablers of Pension Governance

rsinha

Learning Objectives

At the end of this topic, you should be able to answer these questions:

- Who is a fiduciary & fiduciary responsibility?

- What is the significance of fiduciary responsibility, stakeholder communication & block chains for pension governance?

- What is Integrated Information Reporting?

- What are Block Chains & their potential for role in pension governance?

Our analysis of governance so far in this module leads us to conclude that a a mix of structured and unstructured communication integrated with the pension governance process is the best approach to solve the challenges of strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts (SNIC) and broken agency that is characteristic of the relationship between pension subscribers (principals) and financial service providers (agents) in the pension management process. Further we learnt that the ideal mix of structured and unstructured communication will be the use of structured communication as ‘fire alarms; that triggers high intensity unstructured information gathering. We also learnt that to ensure the effectiveness of the ‘fire alarms’ low intensity unstructured continuous communication should be part of the governance process. However, unstructured communication is both costly and at times problematic given regulations on outsider trading.

In this topic we will discuss three enablers that will facilitate unstructured communication at desired levels to ensure effective pension governance. These enablers of unstructured communication are;

- Fiduciary responsibility;

- Stakeholder communication; and

- Blockchains

The analysis shows that these enablers will motivate the use of structured communication such as financial statements as ‘fire alarms’ and not as ‘triggers’ as is the practice in pension governance. The enablers can facilitate a deliberative, process driven governance in a strongly non-contractible incomplete contract environment.

ENABLER 1: Fiduciary Responsibility

A requirement of quality unstructured communication is that principals and agents trust each other. As principal agent relationship is characterized by information asymmetry in contracting environment that is neither independently observable nor verifiable, it is important that principals trust the information and advice provided by the agents. This can only be ensured if the agents recognize their roles as fiduciaries and all agents provide a fiduciary standard of care. This fiduciary standard of care requires that the agents or professionals in the pension management process act in the best interest of the principals to the best of their ability and knowledge using information they have assessed to be reliable. Fiduciary responsibility can be shared but not shifted to another agent. The uncritical use of third-party information by agents in decisions on the principal’s behalf is not considered acceptable as per the fiduciary standard of care.

The efforts to transform agents’ contributions to professional management of pensions into fiduciary roles is on the rise in pension management circles across the world. Strategically, the pension board trustees (board and committee members) are being reminded of their fiduciary roles by legislation and court judgments. In the US, the Department of Labour (DOL) fiduciary rule was proposed but has since been struck down by the courts as a result of concerted efforts by the financial services industry. The courts did not examine the merits of the fiduciary rule but accepted the plea of thefinancial services industry that the US DOL exceeded its area of responsibility. There is also a possibility that the Security Exchange Commission (SEC) will introduce a proposal in this area. The SEC has released an investment advice reform proposal that would require brokers to act in the best interests of clients. The Regulation Best Interest proposal seeks to establishing a standard of conduct for broker-dealers and natural persons who are associated persons of a broker-dealer when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities to a retail customer. The proposed standard of conduct is to act in the best interest of the retail customer at the time a recommendation is made without placing the financial or other interest of the broker-dealer or natural person who is an associated person making the recommendation ahead of the interest of the retail customer.

The trend in court judgements in the US and Canada is not only to remind the pension trustees of their fiduciary duties but also broaden the scope of fiduciary responsibilities to all stakeholders including pension beneficiaries, both of present and future generations. This view of fiduciary duty has implications for pension design and investment decisions. Pension design must be sustainable to meet the obligations of not only current beneficiaries but also of future employees. Investment horizons should also take account of this long-term obligation and not focus on the short-term alone.

Ambachtsheer (2016) provides a check list of six question areas to consider when assessing compliance of pension trustees and in ensuring consistency with the high standards of fiduciary care:

- Pension Design: Do we have a fair, sustainable, understandable pension formula? How can we best address this question? What we would do if our formula doesn’t pass a reasonable fair/sustainable/understandable test?

- Stakeholder Communications: Are we clear about who our stakeholders are? Do we communicate with them effectively about pension design? About the value the pension organization is creating for them? How do we know our communication strategies are effective?

- Organization Design: Do we have a cost-effective organization that pro- duces value for risk and value for money as its key functions? How can we best address this question? What would we do if our organization doesn’t benchmark well in its key functions, using credible metrics?

- Board Effectiveness: How effective are we as a board? Do we have the right mix of skills and experience? Are we seen as trustworthy by our plan stakeholders? Are we public-minded? Do we measure our own effectiveness and improve our own performance?

- Risk Management: What risks do we need to measure and manage? Do we have the people, protocols, and technology to do this well? If not, what are we going to do about it?

- Investment Beliefs and Policies: Do we have an investment program geared to generate plan member wealth through long-horizon return compounding? Is it working well? How do we know? Do we have an investment program geared to meeting the payment obligations to retirees? Is it working well? How do we know?

Ambachtsheer (2016) also advocates collective action by pension funds that together foster long-term thinking in investment decisions that increases the social utility of finance by creating value in the real economy rather than focusing on transactions and arbitrage opportunities as the primary value driver that sustain pension benefits. This will also ensure that the pension investment decisions are consistent with fiduciary standards of care. Evidence is now beginning to emerge that a focus on the long-term and on the real economy in investments will ensure long-term sustainability of pension plans (Barton, Manyika & Williamson, 2017).

ENABLER 2: Stakeholder Communication

In our discussion on the strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts, deliberation based on the exchange of qualitative information is the centerpiece of deliberative process driven governance. We also learned that structured information such as financial reports should not be used as ‘triggers’ but as ‘fire alarms’ in the governance process. The gathering of quality unstructured information is costly, and the information is unique or specific to every organization. The unstructured format of qualitative information is both an opportunity and a limitation. A fine balance must be struck between retaining information content, that is its unstructured and emphasizes organization specific content, and at the same time allowing for cross/intra fund comparisons and benchmarking. The utility of standalone idiosyncratic firm specific information is limited as the interpretation of such idiosyncratic information is difficult in the absence of benchmarks and standardization.

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) has sponsored the Integrated Reporting (IR) framework which seeks to balance the need for detailed organization specific information with the important concern that for such information to be useful it should be comparable and comprehendible to outsiders. The IR is an integrated annual report, compiled primarily to explain how an organisation creates value over time, through various capitals that includes the traditional financial capital always reported on. These capitals represent stores of value that can be built up, transformed or run down over time in the production of goods or services. Their availability, quality and affordability can affect the long-term viability of an organisation’s business model and its ability to create value.

The IR framework identifies six capitals, which are listed as:

- financial

- manufactured

- intellectual

- human

- social and relationship

- natural.

These six capitals are not equally relevant or applicable to all organisations. While most organisations interact with each capital to some extent, these interactions might be relatively minor, or are so indirect that they need not be discussed in the integrated annual report.

Sentinel a South African multi-employer retirement fund is an example of a pension organization that has pioneered the adoption of Integrated Reporting (IR). Sentinel considered the uses or effects of all six capitals when preparing this integrated annual report. However, given the nature of Sentinel’s operations, only four of the six capitals are of enough impact to be reported on. The four capitals reported on are the financial, intellectual, human, social and relationship capitals, while the manufactured and natural capitals are set aside. Sentinel’s exposure to these two capitals is so limited that reporting on these areas is not material. Sentinel sets out specific key performance indicators (KPIs) for each of the capitals for which the organization measures progress against objectives. Shortfalls against objectives may be an early indicator of potential problems to be addressed.

We will discuss IR and KPIs in greater detail in the topic on performance evaluation in the Investment Module.

ENABLER 3: Blockchains

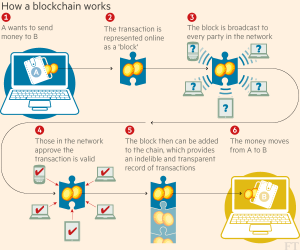

Blockchains can also be an enabler for unstructured communication based endogenous learning in the procedural justice mode. To understand why blockchains can be basis for unstructured communication on demand we will briefly discuss the concept of blockchains and how it can be used to facilitate and enable trust and relationships in unstructured communication. Blockchain is an innovative web-based form that is a mix of distributed computing and cryptography. It was because of an autonomous creator called Satoshi Nakamoto who creatively decided to combine these two elements to create a network of computers that interact to establish and maintain a secured and shared database.In each sector or industry, the use of blockchains is being examined and interpreted in different ways.

For people involved in the finance and business world it is used as a distributed ledger for up to date tracking of transactions. The blockchain was designed so that any recorded information is immutable, in other words a stored information cannot be deleted as it is stored simultaneously in multiple computers in encrypted form. This rules out changing the information as all databases storing the information in an encrypted form can be hacked and changed at the same time. If the information is altered ,the change will have be encrypted recorded and stored as a separate entry another block of information next to the original information. This makes the original data entered and the changes tamper proof. These related blocks of information (original and subsequent changes) are linked together with hash tags and hence the word blockchain.

in a blockchain, every data/information is given a unique badge called the hash. Miners who validate each transaction add them to a block and then post the finished block to other nodes, also known as users, so that a copy of the database is readily available. There is no requirement to verify the alterations to the database. The blockchain therefore depends on a distributed consensus algorithm so that to make entries onto the blockchain all other computers must agree upon its status so that no other computer can make alterations without the approval of others.

There are three main types of Blockchains: Public, Private and Consortium.

A public blockchain is what most people think of when they think of blockchain. It is designed to eliminate the middleman in any transaction of value. It does this by creating peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions via blocks. Each transaction is verified by each node in the system, this is what creates the immutability. Public blockchains offer full transparency of the ledger along with a degree of individual anonymity (according to the specific blockchain). It is most appropriate to use a public blockchain when an organization needs to be decentralized. On the other hand, private blockchains still let the middleman exist, to an extent. Private blockchains are more appropriate in a traditional business and governance model. It allows an organization to write and verify each transaction internally, allowing greater efficiency and speed. The downfall is that it doesn’t offer the same decentralized security as a public chain. However, it includes most of the same beneficial features. In terms of pensions, it allows for greater transparency, and a more efficient corporate governance that works for the principals (pension holders).

A consortium blockchain is semi-private. It provides the same advantages as a private blockchain but is managed by a few selected nodes or users. For example, this consortium can be the board of directors, top management and the adviser to the pension fund. The standard organizational structure of the pension management process discussed earlier in the first topic in this module shows that the consortium block is likely to be the most appropriate block chain for pension management. Blockchains will have a multifaceted impact on pension governance by encouraging unstructured communication. Information will be shared within the consortium with different levels of access being provided to different agents. With the reassurance that the information they are being supplied are verifiable at some level of the blockchain. This is of significance in a SNIC environment where information can be both non-observable and verifiable. The reassurance that information or unstructured communication is verifiable and immutable at specified levels will be force multiplier for the governance process. The knowledge that any decision or recommendation can be verified if required serves SNICs that characterise multi layered principal agent relationships in institutional money management very well.

A permissioned/ demi private or consortium blockchain where investment documents, performance reports, accounting data and other relevant information could be available for all pension holders and any other permissioned stakeholders on as needed basis will serve the requirement of unstructured communication required for the governance of pension plans. Using a permissioned blockchain, a pension fund record of transactions could be recorded permanently with a timestamp, preventing it from being altered. “The company’s entire ledger would then be visible immediately to any permitted stakeholder in a pension’s organizational structure. There will be less reliance and necessity to wait for quarterly financial statements prepared by the firm and its auditors as anyone could aggregate the pension funds transactions. Although this radical change in financial reporting would obviously come at a cost, making proprietary information available to a greater number of stakeholders would have two enormous benefits. Pension fund subscribers would have increased trust in the integrity of the company’s data, and costly auditors (who are themselves corruptible) would not need to be hired to vouch for the accuracy of the company’s books and records”

Blockchains and consortium block chains will also benefit record keeping. Record keeping using blockchain is conducted on a distributed network that is decentralized, meaning it is not controlled by a central authority. This means that records will be stored on multiple computers and these records are immutable meaning you can change them but the history of all the changes is for everyone to verify. Blockchains make it possible to share relevant records on an ongoing basis with the reassurance that at any level more data on transactions and other decisions are on record in multiple nodes and hence immutable. These can be reviewed and hence remove the fundamental constraint characteristic of SNICs – the non-observability and verifiability of information/communication.

We had identified earlier in the topic on modes of learning, the pure procedural justice mode as best suited for principal agent relationships in a SNIC environment. This framework of learning called for the exchange of low-key unstructured communication between principals and agents and the use of structured information such as financial statement as ‘fire alarms’ and not as ‘triggers’ to reward or impose penalties on agents. The intensity of unstructured communication would be increased depending on the status of the fire alarms. Blockchains have the potential to be adopted to meet the requirements of unstructured communication and reduce the scope for opportunistic behaviour in a SNIC environment. Blockchains have the potential for addressing both opportunism as a behaviour and and as an attitude in pension governance. By promoting the feeling for the entity by generating trust blockchains will reduce opportunistic behaviour. By allowing pension subscribers greater access to pension information and facilitating pension plans to adapt with time block chains reduce the scope for opportunism by providing superior prior conditioning.

Blockchain can assist in the preparing and managing plan documents. During plan document preparation, blockchain can help in the review process by tracking and time-stamping the document review by each reviewer and ensuring execution against the most recent versions of documents. It will also enable counterparties to easily verify the authenticity of those documents. The final document can be signed digitally by all signing parties. Access to specific documents or data can be controlled within blockchain. These documents can be stored securely and economically in blockchain (Mehta, Venkatesan, Kapoor & Shetty, 2016). The cost of sharing this information within the pension management hierarchy will also be reduced significantly. With the high speeds and lower transaction costs, using blockchain can significantly decrease the operational costs that current pensions incur. This can help improve the overall bottom line of the pension company that provides higher returns for pensions holders or allow for further reinvestment back into their current system to maximize effectiveness.

Blockchains will also contribute to superior unstructured communication by promoting transparency; control and education of plan providers and subscribers.

Transparency

Blockchain can provide the most transparency possible to allow stakeholders a more comprehensive understanding of how their money is being managed by integrating better governance mechanisms. Other transparency issues that can be eliminated through blockchain are poor performance practices, hidden fees, fraudulent activities and keeping documents and data available for all stakeholders. “When used in an open form with free entry and exit, blockchains generate an archive of transactions known as a distributed ledger, because a copy of each block of transactions is distributed or made visible to all members of the network. The original Haber and Stornetta (1991) paper, in which the blockchain structure was proposed for authenticating intellectual property, suggested this structure to crowdsource the function of auditing and verification. For a pension fund, all trustees and other interested parties would be able to view the arrangement of ownership at any time and identify changes instantly as they occurred. In a private or permissioned blockchain, where the visibility of transactions could be restricted to stakeholders such as trustees and others acting on behalf of the principal, or trusted gatekeepers and investors would enjoy more anonymity. Even under the private or permissioned blockchain models, the real-time archive of transactions would create much more current and complete information about each pension fund and it would be visible to at least some observers” (Yermack, 2017).

This transparency along with the accountability it brings would have a significant impact on the pension management process. Depending on the type of blockchain used it would allow stakeholders of that chain or potentially outsiders (if using a public chain) to observe live trading by managers. A blockchain system would illuminate fund managers’ ownership positions. This visibility could strengthen relative performance evaluation systems. Blockchains coupled with acknowledgement of fiduciary responsibility will also encourage and incentivise trustees and principals to invest in acquiring information about the fund managers transactions and the decisions of multiple.

Control and Education

Blockchains will also have impact on private pension contributions and pension decisions impacted by bounded rationality. Most people are either obligated to contribute to a pension or think that it is the only way to save for retirement, but they don’t treat it as they would any other investment. Education should be a crucial aspect of all pensions, although it is most often overlooked. As noted in the report ‘What Canadians Want from Pensions’ (Baldwin, 2017), there are significant shortfalls, in education between different age groups and income levels. Nearly half of all respondents have no plan. Two out of five have no idea how much they must save and less than one in eight have an accurate idea of how much they must save.

Transparency, control and education will contribute positively to both the feeling of entity and prior conditioning. If intermediaries are not judged solely by quarterly reports the feeling for the entity, the pension plan will improve as they will feel more fairly assessed for their performance. The principals will also be in a better position to assess the process and quality of the decisions taken by the intermediaries instead of focusing on the outcome that is quarterly reports of performance alone. Better education will also lead to a more informed basis for expectation formation by plan subscribers and plan providers. This will contribute positively to prior conditioning and hence reduce the scope for opportunism in the interactions between plan subscribers and plan service providers.

The literature on corporate governance has identified serious neglect in the exercise of voting rights by fund managers in the companies they have significant pension assets invested. Disproportionately, pension fund managers vote in favour of the top management without any evidence of exercise of due diligence in the exercise of the votes. A feature that can be implemented because of blockchain is the ability to record proxy votes. “If proxy voting is conducted on blockchain, participants can vote electronically, and blockchain will provide end-to-end audit ability. Blockchain would also be used to record all the votes for a fraction of the cost. Like current online proxy voting, each participant can be sent a control number that allows the participant to vote electronically. As a result, voting records are more private and secure than if they are kept in a central database. This not only puts more control back into the hands of the pension holder by creating a more sensible corporate governance working for the principal (the pension holder), it incentivizes people to be more interested in the pension investments therefore furthering education and involvement of pension subscribers or principals (OECD, 2017). The exercise of voting rights will also have a positive impact on both the feeling for entity and prior conditioning and thus reduce the scope for opportunistic behaviour.

Labour Market Changes

Block chains will also make pension plans more responsive to labour market changes. The portability of pension plans will also be enhanced by blockchains and this will have design implications for pension plans. Blockchain’s ability to ‘link’ financial transactions together could also be a valuable mechanism for recording an individual’s pension savings. Instead of having a new pension every time there is a job change, the record of a pension plans, and the contributions paid in may be added to my one blockchain, despite the different employers throughout my working life paying to my pension.

This is especially relevant today as it is less likely that a plan subscriber will have continuous lifelong employment anymore. Most will l often cycle through many jobs or freelance before they are even thirty. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but we do need the right pension technological infrastructure to support savings for retirement.

By creating a financial passport via blockchain each person would be able to have his/her own individual chain, that a pension company can maintain for the time of their employment. “Our prototype allows tokens on a chain to be moved to other chains. This allows someone, when they switch employer/pension company, to move their accumulated pension to a new fund. Also, if you allow tokens on a chain to be moved to another, it allows someone to inherit a pension if their spouse passes away or if a kid becomes an orphan (both chains get combined because the tokens although on different chains, have the same value). And we keep the other chain’s meta history as all data in the layer is permanent and immutable, It also allows a pension fund to be absorbed by other funds. If the fund is transferred, they can move all the pensions in the blockchain to a new holder.

Examples

Examples of Pensions looking to adopt blockchain

- OMERS (Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System)

“Ontario pension giant OMERS is pushing further into the rapidly expanding cryptocurrency business through the creation of an Ethereum-focused public company that is planning to raise $50-million.

The company it is backing will be called Ethereum Capital, and is being partly financed by Purpose Investments, a fund management firm led by industry veteran Som Seif and partially owned by OMERS. Mr. Seif will be chairman and co-chief investment officer of Ethereum Capital, which is aiming to raise $50-million from investors and become a public company through a reverse takeover of a TSX Venture shell company.”

Higgins, Stan. California Pension Fund Considers Blockchain Opportunities. CoinDesk. [Online] 2016. https://www.coindesk.com/california-pension-fund-considers-blockchain-opportunities/.

- CalPERS (California Public Employees’ Retirement System)

“Board members of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) recently took part in a discussion on blockchain technology as part of a broader conversation about future investment opportunities.

The meeting is notable given the size of CalPERS, which manages just over $300bn in assets, making it the largest public pension fund of its kind in the US.

In 2009, the pension fund invested $200m in Kholsa Ventures, a Silicon Valley-based venture capital fund, and gave an additional $60m to a seed stage-focused fund run by Kholsa. Just over two years ago, Kholsa led a funding round for blockchain startup Chain, and the fund has also invested in Blockstream, 21 Inc and BlockScore.

Other public pension funds outside of the US have explored investments in the space. Earlier this year, the venture arm of the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) took part in a funding round for VC firm Digital Currency Group.”

Exercises

CONCEPTS FOR REVIEW

- Fiduciary Care and Fiduciary Responsibility

- Suitability Standard

- Modes of Learning

- Stakeholder Communication

- The Integrated Information Reporting Framework

- Block Chains

Exercises

SAMPLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Given the strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts is the Fiduciary Standard or the Suitability Standard, is more appropriate to resolve the agency problem between principals and agents? Discuss.

- What is stakeholder communication? How does it address the governance challenge in pension management?

- Sentinel a South African pension fund used the integrated information reporting framework to promote stakeholder communication. Evaluate its experience in resolving the governance challenge in pension management.

- What are block chains? How can block chains be used to promote transparency and superior governance of pensions?