Topic 2: Pension Governance – The Role of Learning

rsinha

Learning Objectives

At the end of this topic, you should be able to answer these questions:

- What is the ‘broken agency problem’? Why does it apply to pension governance?

- What are strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts (SNIC)?

- What is the role of learning in SNIC?

- What is the distinction between self-interest and opportunism

- Why is opportunism a better basis for identifying the learning mechanism for SNICs

- What is the distinction between opportunism as an attitude and opportunism as a behaviour

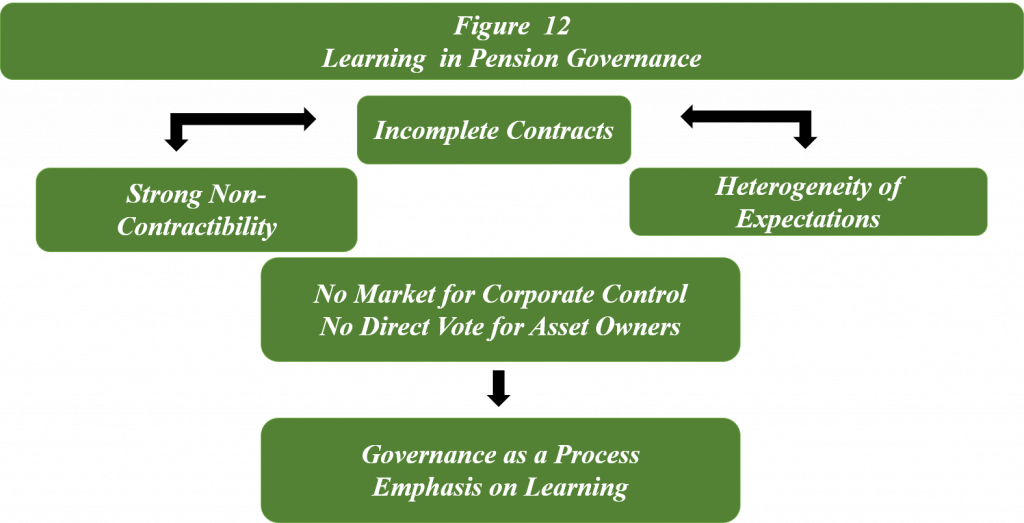

We learnt earlier in this module that the role of governance mechanism is to bridge the incomplete contracts between principals and their agents. The literature on corporate governance is vast. However, the evidence from this literature cannot be applied to pension governance without accounting for the specific attributes of pension management. First, pension decisions are intertemporal, their implications extending over multiple generations. Second, the agency relations are multilayered and complex as outlined in Figure 10. Third as summarised in Figure 12, not all mechanisms of corporate governance are available or effective in resolving the agency conflicts in pension governance. The availability and effectiveness of individual governance mechanisms will also depend on the pension plan design and ownership of assets. These distinctive attributes require that we develop a framework of governance that account for the specific context of pensions. This what we will do next. The goal is to identify a pension governance framework that not only ensures accountability and control but also provide a superior decision context for pension management.

Governance as a Process – the broken agency problem

The specific challenge of governance of pensions is characterized by Clark and Urwin (2017) as the ‘broken agency’ problem. The concept of broken agency is borrowed from the literature on infrastructure construction and governance. Pension and the infrastructure industry both share an intertemporal decision horizon. This implies that the outcomes of decisions will evolve and be apparent after a long period of time. Also as in the case of pensions there are multiple agents involved in the construction and management of infrastructure projects.

Henisz & Levitt (2009) describe the broken agency decision problem as follows: separate individuals, different departments within an organization, or different companies incur the costs without sharing common accountability, the risks and benefits associated with each phase of a building project’s life cycle, so no individual or firm on the project has a truly multidisciplinary, life cycle perspective. The individual or firm that bears capital costs does not usually bear the full lifecycle operating costs. Overall project benefits may conflict with individual participants’ self interests and so tend to be ignored. This “broken agency” is present in each phase of a building’s life cycle because of vertical fragmentation of the industry (Henisz & Levitt, 2009).

Recall Figure 10 on pension management structure in the previous topic. Clark and Urwin (2017) propose that a similar ‘broken agency’ exists in the context of pension management. The decision horizon is intertemporal and as the figure on pension management in the previous module shows, the financial services industry is similarly vertically integrated and there are many entities in the financial services industry that contribute to costs and benefits that are shared on an asymmetrical timeline. The agents are not compensated after the final outcomes of the pension assets or proportionally to the payouts based on defined benefit plans. The compensations to the agents are in the short-term and the perceived benefits of their decisions are only realized in the very long-term. A pension governance aiming to ensure accountability, control and a superior decision context has to account for the ‘broken agency’ aspect of pension management.

As pointed out earlier, governance mechanisms are needed because of the incomplete contracts between principals and their agents. Schwartz (1992) lists five reasons for contractual incompleteness:

- Vague wording of the contracts;

- Failure to contract an issue;

- Prohibitive cost of writing a complete contract;

- Asymmetric information between the contracting parties; the asymmetric information may or may not be observable and verifiable ex post. A contract is considered weakly non-contractible if the asymmetric information can be observed but cannot be verified ex-post. A contract will be strongly non-contractible if the information can neither be observed nor verified ex-post.

- Heterogeneity, or variations in expectations; another source of contact incompleteness is heterogeneity or variations in expectations on one side of the market. Given this heterogeneity, a complete contract will be drawn if the uninformed principals can screen the informed type. Contracts will be incomplete when the screening is not feasible or when the informed agent cannot disclose the information credibly.

The key objective of pension governance is to observe and verify on behalf of the principals, the actions and their outcomes, of the multiple agents involved in pension management in an incomplete contract environment. Incomplete contracts we have noted earthlier in the previous topic can be of two types – strongly non contractible and weakly non-contractible. If the contracts are strongly non-contractible the verification and observability of such incomplete contracts cannot be based on exogenous criteria. In such a contracting environment, verification will be a function of the subjective interests of the parties involved. At any point in time the principal will get some information on the extent of fulfilment of the contract and receive information that allows the principal to form expectations regarding the possibilities being fulfilled in the future. New expectations may also be added to the incomplete contracts. Thus, the degree of observability and verifiability is endogenous to the incomplete contracts.

Figure 12. Learning in Pension Governance

The relationships between the principals, the pension plan subscribers and their agents, the financial services providers, are based on strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts or SNICs. Pension decisions are intertemporal and are embedded in ‘broken agency’ relationships. Expectations of pensioners can change over the life time of the pensioners or the principals. It would be simplistic to assume that these expectations and obligations are completely identified at the commencement of the pension plan membership and remain unaltered during the process of accumulation and deaccumulation of pensions. The pensioner is likely to receive updates and information that induces them to revise their plans and expectations about the future. For example, the plan subscriber may add new expectations depending upon changes in their circumstances such as in employment or health. An added attribute of the strongly non-contractible incomplete contract is that the decision context is embedded in the ‘broken agency’ context. These attributes of the incomplete contracts between pension subscribers and their agents or plan service providers makes it difficult to observe and verify the strongly non-contractible incomplete contracts.The requirements of this observability and verification process we examine next.

Endogenous Learning Mechanisms: Characteristics

With SNICs, observability and verification has to be endogenous to the governance process and not based on externally observable criteria or reporting. This will require a learning mechanism. Next we will explore what will be the characteristics of such an endogenous learning mechanism. Learning is not just a passive exchange of information between principals and agents. It is about how information is accrued and how it is processed. Learning acquires significance not only in the minimization of the agency problem but also the basis for superior intertemporal pension decisions as it will facilitate the ongoing interpretation of SNICs for both pension plan subscribers and the various financial service providers. .

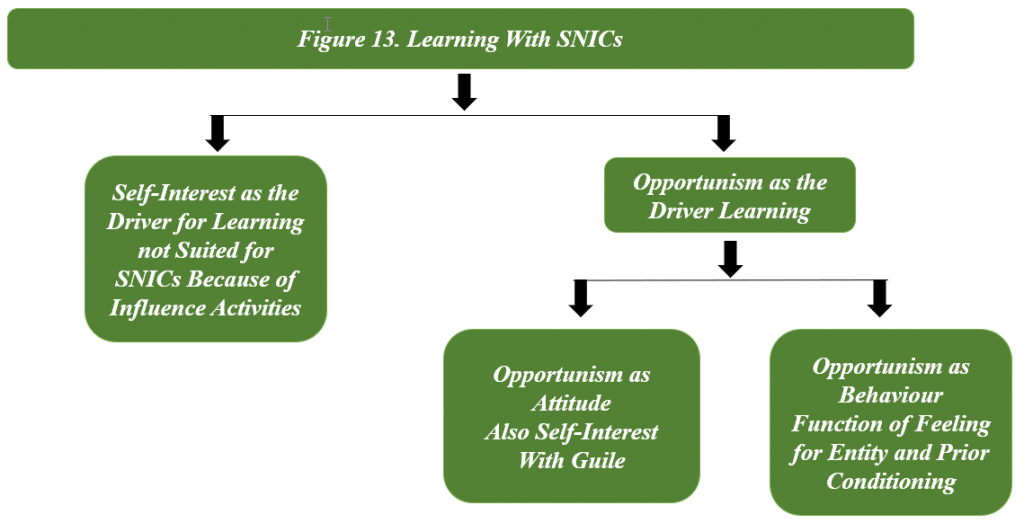

Figure 13. Learning With SNICs

In the rational actor framework, self-interest is a primary driver for learning between principals and agents. However, most information is not innocent and suffers from misrepresentation as it is gathered and communicated in the context of self-interest and with an awareness of decision consequences. Milgrom and Roberts (1988) term such information manipulation and activities ‘influence activities.’ Ghosal and Moran (1995) contend that self-interest is inadequate as an explanation for learning in the principal agent interaction based on SNICs. The assumption of self-interest results in decision behaviour is motivated by the agent’s preferences. Self-interest assumes that the agent will disclose all pertinent information and meet all obligations expected of him that are consistent with the exercise of self-interest. However, in pension governance we have three factors to consider:

- strong non-contractibility;

- heterogenous expectations that given their intertemporal horizon are evolving; and

- broken agency relationships

The presence of these factors in pension governance relationship between principals and agents implies that we cannot assume that all pertinent information is disclosed. It may well be that in the information is not yet in the cognitive frame of the principals and agents or not observable or verifiable.

Ghosal and Moran (1995) describe the incentive structure in the principal agent relationship of pension governance as opportunism. Opportunism is self-interest pursued with guile. Opportunism recognizes the role of influence activities in the observability and verifiability of information as in SNICs characterized by heterogenous expectations and ‘broken agency’. Recognition of opportunism implies that agents will not disclose all obligations expected of them and fulfill all obligations under the contract. A superior learning mechanism can be identified when we incorporate opportunism and not self-interest as the basis for sharing information in the interactions between principal and agent in pension management.

A more sophisticated learning mechanism can be identified when we make a distinction between opportunism as an attitude and opportunism as a behaviour. The former is a product of the human condition and the latter a product of institutions and technology. Opportunism as an attitude involves the proclivity or inclination of the individual to act opportunistically to pursue self-interest with guile. Opportunism as behaviour is positively related to expected benefits and is negatively related to safeguards and controls in the institutional and technological environment. Thus, opportunism as behaviour can be a variable of the institutional context. In the design of an endogenous learning mechanism in pension governance, we must recognize the existence of these two forms of opportunism. A learning mechanism that exclusively focuses on incentivising opportunism as an attitude, that is aligning self-interest of agents to the principals or pensioners, is not likely to succeed because of SNICs. Corporate governance focuses in publicly listed companies on the use of stock options to align top management incentives with shareholders has had limited success and was distortionary as noted in multiple accounting scandals involving top management[1]. Enron and WorldCom are the more dramatic examples of the turn of this century and ever so often we are reminded of similar corporate episodes of to top management malfeasance. When the primary reliance of executive compensation was on stock options, they became a disproportionate share of top management’s net worth. This was the primary reason for various accounting manipulations by top management in their effort to protect their own net worth. Moreover, incentivising fund managers by linking their compensation to quarterly or annual returns is not a good match of the investment horizon of pensioners with the career horizons of the fund managers.

The strong non-contractibility and heterogeneous expectations characteristic of pension governance in a broken agency context requires an emphasis on learning mechanisms that focuses on opportunism as a behaviour.The focus on opportunism as a behaviour does not imply that the governance mechanism do not account for opportunism as an attitude. The structure of the governance process will be such that in the design of external or exogenous criteria to curtail opportunism as an attitude care will be exercised that these very mechanisms do not exacerbate opportunistic behaviour. It is important to remember that opportunistic behaviour will be difficult to observe from the outside. Thus stock options to motivate top management to behave in the interest of shareholders is an example of an exogenous criteria designed to curtail opportunism as an attitude. However, as these stock options are a large proportion of the management’s compensation and net worth, they have been a significant influence on management decision behaviour that have reduced shareholder value as several high profile examples have shown. .

Two factors influence opportunism as a behaviour, prior conditioning and feeling for the entity. Prior conditioning will be a function of the social cultural and political norms of each society. An example of prior conditioning in the corporate governance of publicly listed corporations is the choice between profit maximization versus stakeholder theory as the goal of the firm. For pensions, prior conditioning will be in the social contract environment underpinning the pension system a country. In the privately funded and privately managed pension quadrant, prior conditioning could be provided by the perspective on income replacement rate (IRR) and recognition of fiduciary responsibility as the basis for the relationship between pension subscribers and pension plan providers.If plan subscribers believe that pensions are an opportunity to realize life long aspirations and not just old age financial security then this will lead to a different set of expectations and opportunistic behaviour. Pension plan subscribers will expect higher returns on their pension savings/assets. Given the risks that will accompany such high return strategy pension service providers will invest with short term goals as there is little evidence to suggest that high returns strategy can be sustained in the long run.

Opportunism as a behaviour will also be a function of the feeling for entity. This perception emerges from the contracting parties’ assessment of each other. Thus, if we continue to focus on financial transactions and quarterly financial returns or what Keynes referred to as ‘beauty contests’, the feeling of entity is not engendered in the relationship between plan subscribers and plan service providers. Thus, opportunism as a behaviour becomes endogenous to pension governance. If fund managers are judged primarily on quarterly reports or what Keynes termed as ‘beauty contests’, it will reduce the feeling for entity or for the relationship between principals and agents. We now have extensive evidence that it is difficult to beat the market on a consistent basis purely based on financial transactions based on arbitrage opportunities. We know that active management and market timing do not yield above market returns and raises the cost of asset management (Ambachtsheer, 2016). This has led to a growing assertion now increasingly backed by empirical data that pension management outcomes will be superior if the focus is on metrics for long-term investments and not on quarterly performance reports. A focus on the long term away from ‘beauty contests’ and quarterly reports will lead to a decision environment where potential for opportunism is reduced. This will be possible if we are able to identify and adopt long-term metrics and flow of information between the principals and agents.

The detailed discussion and identification of the incomplete contracts between owners of pensions funded assets and agents entrusted with their management highlights the important role of learning in the governance of funded pension assets. The learning process to bridge the incomplete contracts between pension owners and the various levels of the financial services industry or the agents has to incentivise opportunism as an attitude but the focus has to be on reducing opportunism as a behaviour. This will require prior conditioning and a feeling for the entity in the management of incomplete contracts. At a higher level, both these requirements will be a function of the social contract environment of the national pension system. At an operational level this will mean an important role for a formalized regulatory structure, recognition by the agents of their fiduciary role and a standardized integrated reporting structure that is transparent and reliable. We discuss this in the next two topics.

Exercises

CONCEPTS FOR REVIEW

- The Broken Agency Problem

- Strongly Non-Contractible Incomplete Contracts

- Self-Interest as a Learning Mechanism

- Opportunism as a Learning Mechanism

Exercises

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What is the ‘broken agency’ problem? Why does it apply to pension management? Explain.

- Discuss the implications of SNICs for pension management.

- Given influence activities why opportunism and not self-interest will be the basis for learning in a contract environment characterized by SNICs; heterogenous expectations and a ‘broken agency’?

- Why should we focus on opportunism as a behaviour in the design of learning mechanism? What implications does opportunism as a behaviour have for pension investments?