Where Are You?

![]()

Speaking to You from Where You Are

If you are here, then you are at least curious about what Humanizing Education could mean. Maybe that curiosity stems from skepticism, perhaps well-meaning curiosity, or maybe you are fully invested in the concept already. Regardless, we welcome you and ask you to take this journey with us to learn more about what Education can be and what role you have in making it more. In all your activities within the University or College, you are making decisions that have cascading impacts on others — and that is true for all of us: administrators, instructors, students, staff, etc. Would you like to know how you can help “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all?” Let’s begin.

We, and many others, believe that access to education (materials, experiences, and interactions) is fundamental to achieving inclusive and equitable quality education for all. We are involved in efforts to improve all three, but for the purposes of the work we have undertaken here, we want to focus on the interactional: on humanizing the endeavor altogether. At its least, “humanizing education” means recognizing that we are all human. So, we start with an awareness of what it means to be human together, namely: where there are people there are also power dynamics, systemic and historical cycles of exclusion, privilege, and inequitable access.

Education (both teaching and learning) must be understood as relational, situated, and embedded in socio-economic cultural phenomena. And this is not just a situatedness that represents where the instructors and students are — administrators and decision-makers within the University or College should also explore their own situatedness. It is in the relational moments that education transcends mere content, rote memorization, and standardized assessments and moves to the realm of sustainable learning outcomes, application of concepts, great personal growth, and yes, equitable access.

In some cases, technologists have tried to solve this by building in surveillance mechanisms to flag students falling behind. They have built in ways for instructors to connect with students other than just in classes or during office hours. Each of those attempts creates the context where the relational can happen, but they do not in and of themselves create relational connections. Those connections happen in the details of how we treat each other.

We need to do the following, and not as a task or a checklist, but as a foundational value:

- Ask “Education for whom?” in every decision we make and every plan we scale

- Establish meaningful ways to talk with and listen to each other

- Build in mechanisms for change and flexibility

- Build in opportunities for reflection

- Build in Codes of Conduct and ask what else needs to be done to make a space inclusive and challenging

- Explore how pedagogies of care, trauma, and kindness impact outcomes like innovation, success, retention, motivation, meaning-making etc.

At this time, many academic institutions are using some variation on many of the words above: wellness, care, trauma, inclusion, critical pedagogy, humanizing, and more. What the institutions do about those words makes all the difference. Whether we or our institutions are up front about where we are on this journey, it is detectable in the ways we handle communications, activities, and controversies. The era of “thoughts and prayers” and “wellness theatre” cutting through the real experiences of individuals in times of crisis or unrest has come to an end. We can do better; we must do better. In other words, neither the existence of a statement, policy, or standard without follow through or the absence of a statement, policy, or standard can absolve us of having to address what is currently impacting education:

- Student and instructor well-being

- Inequities that have a disproportionate impact on some

So, the question we pose to you, good reader, colleague, and collaborator in Education is: Where are you? Below are three possible (yes, overly simplified) states you find yourself in as you engage with these modules:

1. Framework

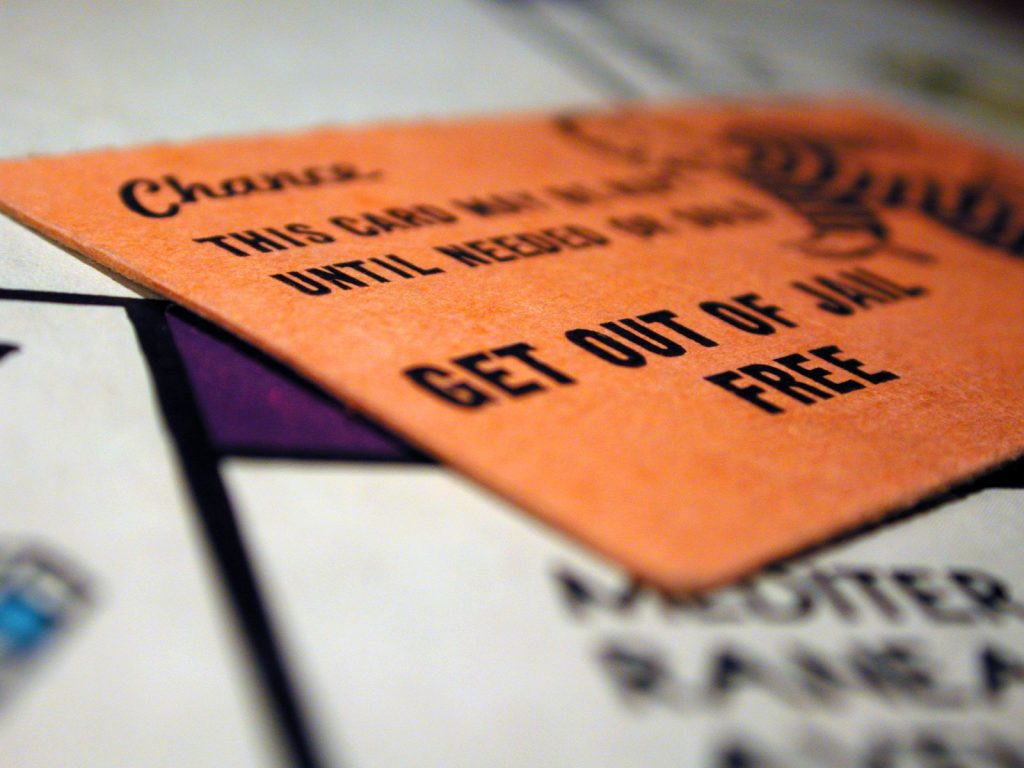

In this first scenario, when we are confronted by a situation that is particularly messy, we turn to a framework for understanding it and for dealing with it. We might look to the following for guidance on how to proceed:

- The rule of law

- The rules of the game

- The mores of the culture

- The mores of the institution

Figure 1: Get Out of Jail Free card from Monopoly By Mark Strozier — [1], CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55376860

This is the easy way to know what to do — a disembodied source tells us what to do, we go straight to action, and we do what has been dictated, what has been done before, what is tried and true, and what has, presumably, been checked for legality/propriety/cover your *ssness. We follow instructions. This is not a humanized approach, but rather one that relies on well-formed policies determined with a process that is often not transparent, clear, or know-able.

Examples of this approach can sound like any of the following:

- That’s the way we have always done it

- We have a policy that states we can/can’t do that

- That would upset <insert stakeholder here> and we can’t do that

- ‘NMP’ principle — not my problem — above my pay grade, out of my hands, etc.

- HR or legal has a policy that tells us what we should do — this is their domain and we’ll defer to them

The “framework” approach is not often associated with innovation or culture change or humanizing. This approach tends to double-down on the litigious, immediately escalating many issues that point to failures or points of conflict in the institution that could and should be addressed. And policies that attend to human interactions tend to establish the very minimum; they are not often forward thinking or innovative.

2. Token

When we don’t have a framework, we might look for a way to SOLVE the problem — if there isn’t a woman in a senior leadership role, we bring in a woman. If there isn’t a person of colour or an Indigenous person, we bring one in. We’re always one step behind, but we’re responsive! And we are still under the illusion that these sorts of representational issues can be solved or fixed, that it will be completed, checked off a to-do list if we simply substitute in what has been identified as missing. The problem is that both the context and the people will change and then there will be another “missing” person. Another problem is the disproportionate weight put on a “representative” individual to speak not for themselves, but for an entire identity group while the other members of the group are “just themselves.”

This approach has no awareness of the dynamism of people, communities, and individuals: we cannot be simplified to checklists or boxes; there is no completion. So, we have a student-centred event or week; we praise the sessional instructors publicly; we applaud the flexibility of those who have embraced care, kindness, and humanizing in their teaching; and we ultimately change nothing — worse, we double down on policies and practices that reinforce inequities.

In this quick recovery scenario, we run the risk of

- Tokenism

- Superficially dealing with a complex issue (and ultimately changing nothing for the future)

- Not being respectful to nuance

- Marginalizing — exactly what we are aiming to avoid

- Unintended consequences (slippery slope arguments like “if I make an exception for you …”)

- Establishing a culture of haves and have-nots, creating (arguably unnecessary and counterproductive) competition

Figure 2: Image of all white people with one person of colour in the middle, circled “Here I am again!” https://www.congressheightsontherise.com/blog//2011/08/minority-report-white-is-new-black-in.html

When we immediately try to solve, we miss opportunities for deeper and broader engagement and understanding. This often means we do not address the root causes and get stalled out at a potentially superficial level.

Examples where this approach can be detected are:

- We have a person of colour on our board now

- We have a diversity day/month/T-shirt/sticker

- We have a diversity checklist we go through on all projects and this is how we show our commitment

- We did an afternoon of training around biases, we’re good

- We have a fact sheet for different disabilities that all are required to read

From the perspective of the marginalized person in an environment like this, the question becomes: Am I a token or do they respect my mind/ideas/work/perspective?

The “token” approach is not often associated with innovation or culture change or humanizing. This is also often easily sniffed out and is transparent to outsiders. It tends to stick out like a sore thumb.

3. Depth/Breadth

When we don’t stop at the answers/rules/laws (framework) and we acknowledge the superficiality of subbing in the missing puzzle piece (token), then we have an opportunity to create dialogue/respectful disagreement/sharing of diverse ideas, to change culture and be innovative , to lead and show others how it can be done productively, meaningfully, and sustainably. We can do the hard work to change culture, build communities, and have practices that reflect the words we write.

In this scenario, it is important to remember that

- How things begin matters (look through history to understand where you are now)

- Representation matters — striving for co-design with rather than for should be a minimum

- Language matters

- Framing the issue matters (vulnerability, truth-telling, honesty, apology)

- Setting the expectations for outcomes/timelines matters (goals, success, failures). Whose notion of success? Who defined the goals and are they singular? What do we do with failures?

- Participation matters

- It is unlikely that everyone will be happy — conflict can be productive

Figure 3: Burns, Brittani. “We Welcome” Unsplash. August 11, 2018, https://unsplash.com/@brittaniburns.

If you’re looking for these examples, you’re also often looking for moments of failure, of discomfort, of uncertainty. These examples extend beyond that initial point of failure, discomfort, or uncertainty, to where we can see those in power or those responsible go into action that can then result in real change. This is not accomplished through one-off events or statements or press conferences or moments that make the uncomfortable individual feel better, but rather are characterized by at least the following:

- Apologizing authentically

- Focusing on and acknowledging the injustice done

- Addressing those who were hurt by the misstep

- Actual and sustainable action to remedy the misstep that makes it unlikely to occur again.

I started writing In The Heights because I didn’t feel seen.

And over the past 20 years all I wanted was for us–

ALL of us– to feel seen.

I’m seeing the discussion around Afro-Latino representation

in our film this weekend and it is clear that many in our

dark-skinned Afro-Latino community don’t feel sufficiently

represented within it, particularly among the leading roles.

I can hear the hurt and frustration over colorism, of

feeling still unseen in the feedback.

I hear that without sufficient dark-skinned Afro-Latino

representation, the work feels extractive of the community

we wanted so much to represent with pride and joy.

In trying to paint a mosaic of this community, we fell

short.

I’m truly sorry.

I’m learning from the feedback, I thank you for

raising it, and I’m listening.

I’m trying to hold space for both the incredible

pride in the movie we made and be accountable

for our shortcomings.

Thanks for your honest feedback. I promise to do

better in my future projects, and I’m dedicated to the

learning and evolving we all have to do to make sure

we are honoring our diverse and vibrant community.

Siempre, LMM

Figure 4: Lin Manuel Miranda apologizing on Twitter

There are those in Education who understand that change requires an intersectional approach bridging technology, humanity, and their interplay therein. Christine Ortiz, former Dean of Graduate Education, Professor of Material Science took leave several years ago to “imagine a university without classrooms, lectures, disciplinary departments, or majors.” Ortiz imagined a university focused on:

- The transdisciplinary interface between technology and humanity

- Emphasizing personalized, holistic, and research-based pedagogy

- Employing dynamic organizational structures and a high quality, low cost, scalable financial model to serve more underserved and underprivileged students

Activities like Ortiz’s imagined Institution should push us to interrogate just how far we are pushing ourselves and others around us to unlearn and unsettle, just how much we are empowering students to be agents of their own diverse destinies, just how much effort and time we are putting into creating and maintaining inclusive communities, and how we are working to sustain a practice of critique and questioning.

An apt metaphor to demonstrate this meaningful depth and breadth is to imagine a diverse group of people coming together to co-create a table. Rather than assume common mores and practices, rather than inviting “others” to take a seat at a table already constructed and codified with institutional norms and histories that form the basis of “ways of doing things,” co-creating the table means authentically bringing people together to build a table with each other. Rather than adding additional seats at the table, those invested in depth and breadth work to tear down existing table structures and co-create spaces and tables with everyone[1]. In order to do this, we need to ask questions such as “What should the table be made from and what direction will it be oriented toward?” and “How do we ensure both flexibility and structures are in place that allow for continued co-construction of the table?” By exploring these questions, we can ensure that tables are built that move from inclusion to true belonging, wherein folks at the table are truly heard.

Continuum

The above three scenarios do not convey a linear progression of discrete states — some institutions or individuals start at depth/breadth and remain there through hard work, actively nurturing a healthy culture while making clear their ongoing commitment to a humanized approach. Some merely start there. Each of these scenarios show some level of awareness of the problem and a different approach to the opportunity. What we are hoping to show here is that openness and inclusion are not immeasurable. They can be sniffed, seen, documented, practiced, lost, and gained. In the context of education, these approaches can break down barriers to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal #4: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” If we do not heed the opportunities as institutions, then not only will we not achieve Goal #4, we will be complicit in perpetuating a system or process that reaches only some while actively harming others.

This is our call-to-action: Are we satisfied with reaching only some or do we see ourselves as committed to optimizing education for all? Are we part of rethinking education, or will we maintain the status quo?

Where Are You?

Skeptics, well-meaning allies, and fully invested champions, we are all a part of this aspect of education: the relational. So, join us in exploring ways you can continue to humanize your own practice.

- https://jesshmitchell.medium.com/open-and-inclusive-how-we-get-both-wrong-1f908a9517c7 ↵