2.2 – Respiratory Structures and Their Function

Simone Laughton

The content of this chapter was adapted from the Concepts of Biology-1st Canadian Edition open textbook by Charles Molnar and Jane Gair (Chapter 20 -The respiratory system).

|

2.2. Describe select respiratory structures in aquatic and terrestrial animals. |

Ventilation and Perfusion

Two important aspects of gas exchange in the lung are ventilation and perfusion. Ventilation is the movement of air into and out of the lungs, and perfusion is the flow of blood in the pulmonary capillaries. For gas exchange to be efficient, the volumes involved in ventilation and perfusion should be compatible. Therefore, ventilatory structures and perfusion surfaces have evolved to maximize this compatibility in both aquatic and terrestrial environment and examples of such structures and surfaces will be provided next.

Skin and gills

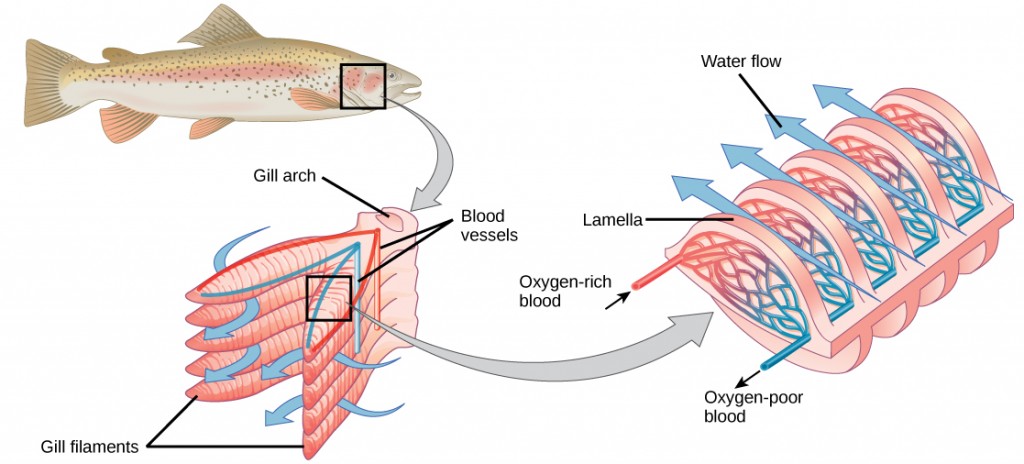

Fish and many other aquatic organisms have evolved gills to take up the dissolved oxygen from water (Figure 2.4). Gills are thin tissue filaments that are highly branched and folded. When water passes over the gills, the dissolved oxygen in water rapidly diffuses across the gills into the bloodstream. The circulatory system can then carry the oxygenated blood to the other parts of the body. Some animals contain a body cavity known as the coelom which is filled with coelomic fluid needed for gas exchange and locomotion. In this case, oxygen diffuses across the gill surfaces and into the coelomic fluid instead of blood. Gills are found in mollusks, annelids, and crustaceans.

The folded surfaces of the gills provide a large surface area to ensure that the fish gets sufficient oxygen. The concentration of oxygen molecules in water is higher than the concentration of oxygen molecules in gills. As a result, oxygen molecules diffuse from water (high concentration) to blood (low concentration), as shown in Figure 2.5. Similarly, carbon dioxide molecules in the blood diffuse from the blood (high concentration) to water (low concentration).

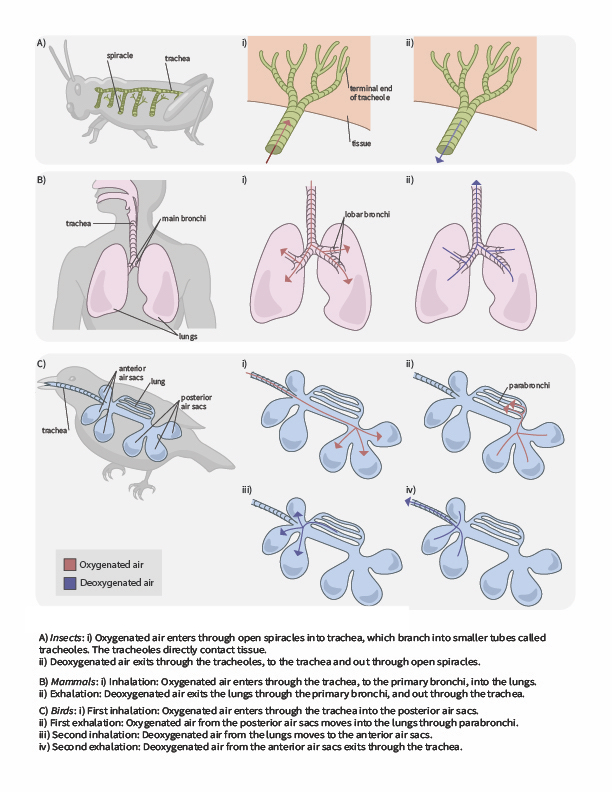

In terrestrial environments, animals showcase a diversity of respiratory system adaptations to obtaining oxygen (Figure 2.6), such as treachea in insects, alveoli in mammals and parabronchi in birds. You can also use the following gif animation as an overview of how air moves through respiratory system structured of a few terrestrial animals.

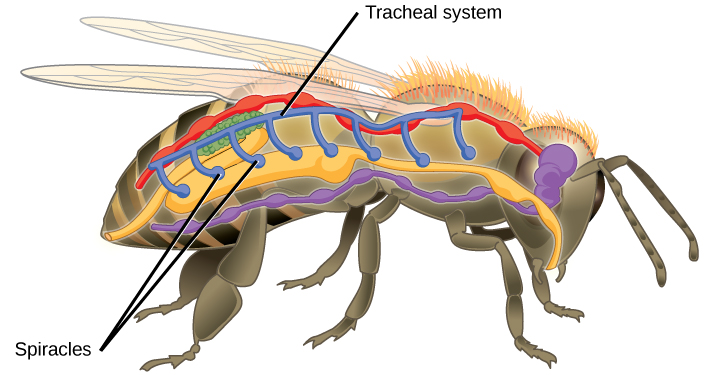

Insect respiration is independent of its circulatory system; therefore, the blood does not play a direct role in oxygen transport. Insects have a highly specialized type of respiratory system called the tracheal system, which consists of a network of small tubes that carries oxygen to the entire body. The tracheal system is the most direct and efficient respiratory system in active animals. The tubes in the tracheal system are made of a polymeric material called chitin.

Insect bodies have openings, called spiracles along the thorax and abdomen. These openings connect to the tubular network, allowing oxygen to pass into the body (Figure 2.7) and regulating the diffusion of CO2 and water vapor. Air enters and leaves the tracheal system through the spiracles. Some insects can ventilate the tracheal system with body movements.

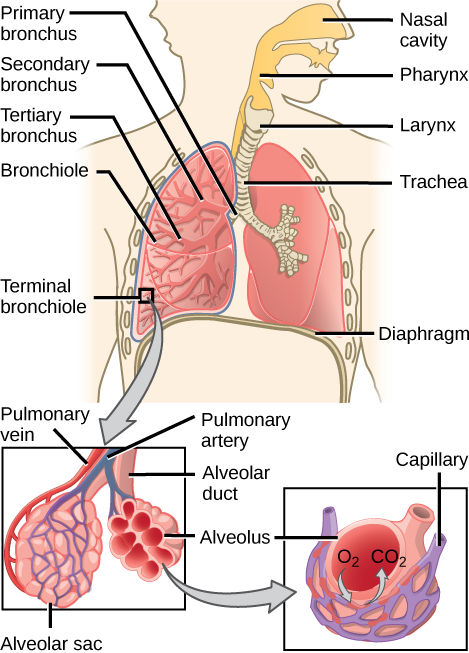

In mammals, pulmonary ventilation occurs via inhalation (breathing). During inhalation, air enters the body through the nasal cavity located just inside the nose (Figure 2.8). As air passes through the nasal cavity, the air is warmed to body temperature and humidified. The respiratory tract is coated with mucus to seal the tissues from direct contact with air. Due to the high content of water in the mucus, the air picks up water as it crosses the surfaces of mucous membranes. These processes help equilibrate the air to the body conditions, reducing any damage that cold, dry air can cause. Particulate matter that is floating in the air is removed in the nasal passages via mucus and cilia. The processes of warming, humidifying, and removing particles are important protective mechanisms that prevent damage to the trachea and lungs. Thus, inhalation serves several purposes in addition to bringing oxygen into the respiratory system.

|

Question 2.4

Which of the following statements about the mammalian respiratory system is false? |

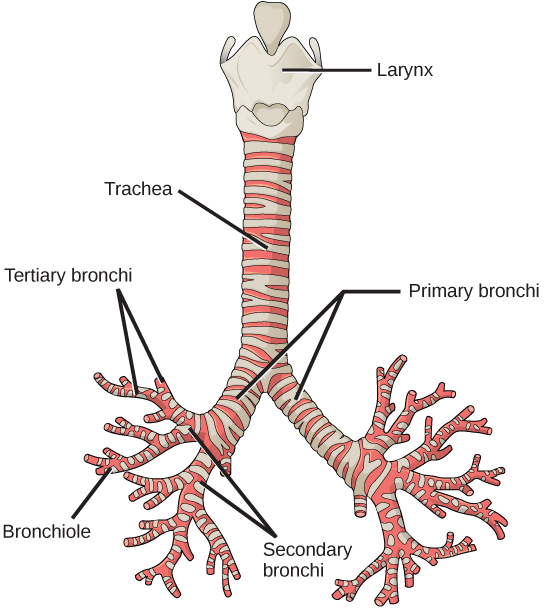

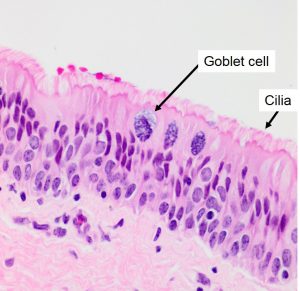

From the nasal cavity, air passes through the pharynx (throat) and the larynx (voice box), as it makes its way to the trachea (Figure 2.9). The main function of the trachea is to funnel the inhaled air to the lungs and the exhaled air back out of the body. The human trachea is a cylinder about 10 to 12 cm long and 2 cm in diameter that sits in front of the esophagus and extends from the larynx into the chest cavity. From there, it divides into the two primary bronchi at the mid-thorax. It is made of incomplete rings of hyaline cartilage and smooth muscle (Figure 2.9). Smooth muscles can contract or relax, depending on stimuli from the external environment or the body’s nervous system. When the smooth muscles contract, they decrease the trachea’s diameter, which causes the expired air to rush upwards from the lungs at a great force. The forced exhalation helps to expel mucus when we cough. The trachea is lined with mucus-producing goblet cells and ciliated epithelia. The cilia propel foreign particles trapped in the mucus toward the pharynx. The cartilage provides strength and support to the trachea to keep the passage open.

Based on your understanding of the respiratory structures and functions, choose the best answer:

Lungs: bronchi and alveoli

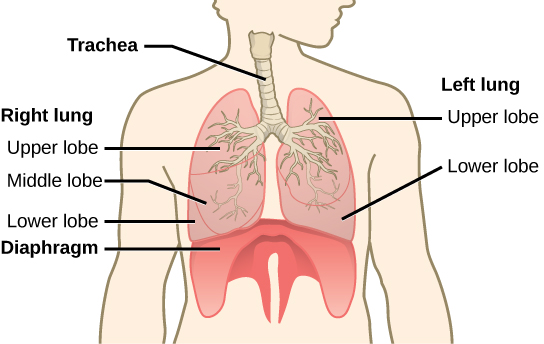

The end of the trachea bifurcates (divides) to the right and left lungs. The lungs are not identical. The right lung is larger and contains three lobes, whereas the smaller left lung contains two lobes (Figure 2.10). The muscular diaphragm, which facilitates breathing, is inferior (below) to the lungs and marks the end of the thoracic cavity.

[caption] Figure 2.10. The trachea bifurcates into the right and left bronchi in the lungs. The right lung is made of three lobes and is larger. To accommodate the heart, the left lung is smaller and has only two lobes.

In the lungs, air is diverted into smaller and smaller passages or bronchi. Air enters the lungs through the two primary (main) bronchi (singular: bronchus). Each bronchus divides into secondary bronchi, then into tertiary bronchi, which in turn divide, creating smaller and smaller diameter bronchioles as they split and spread through the lung. Like the trachea, the bronchi are made of cartilage and smooth muscle. At the bronchioles, the cartilage is replaced with elastic fibers. Bronchi are innervated by nerves of both the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems that control muscle contraction (parasympathetic) or relaxation (sympathetic) in the bronchi and bronchioles, depending on the nervous system’s cues. In humans, bronchioles with a diameter smaller than 0.5 mm are the respiratory bronchioles. They lack cartilage and therefore rely on inhaled air to support their shape. As the passageways decrease in diameter, the relative amount of smooth muscle increases.

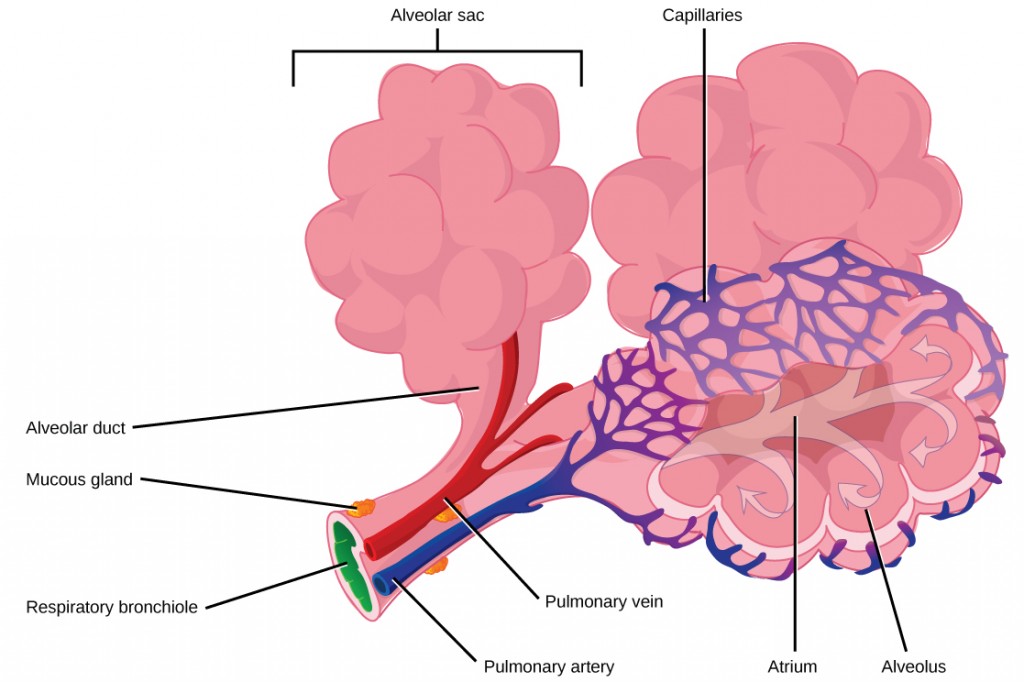

The terminal bronchioles subdivide into microscopic branches called respiratory bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles subdivide into several alveolar ducts. Numerous alveoli and alveolar sacs surround the alveolar ducts. The alveolar sacs resemble bunches of grapes tethered to the end of the bronchioles (Figure 2.11). In the acinar region, the alveolar ducts are attached to the end of each bronchiole. At the end of each duct are approximately 100 alveolar sacs, each containing 20 to 30 alveoli that are 200 to 300 microns in diameter. Gas exchange occurs only in alveoli. Alveoli are made of thin-walled parenchymal cells, typically one-cell thick, that look like tiny bubbles within the sacs. Alveoli are in direct contact with capillaries (one-cell thick) of the circulatory system. Such intimate contact ensures that oxygen will diffuse from alveoli into the blood and be distributed to the cells of the body. In addition, the carbon dioxide that was produced by cells as a waste product will diffuse from the blood into alveoli to be exhaled. The anatomical arrangement of capillaries and alveoli emphasizes the structural and functional relationship of the respiratory and circulatory systems. Because there are so many alveoli (~300 million per lung) within each alveolar sac and so many sacs at the end of each alveolar duct, the lungs have a sponge-like consistency. This organization produces a very large surface area that is available for gas exchange. The surface area of alveoli in the lungs is approximately 75 m2. This large surface area, combined with the thin-walled nature of the alveolar parenchymal cells, allows gases to easily diffuse across the cells.

|

Question 2.5

Which of the following statements about the human respiratory system is false? |

|

For further interest and comparison of human lungs with other animal respiratory systems, here is a link to an interesting article. |

Pulmonary ventilation is the act of breathing, which can be described as the movement of air into and out of the lungs. The major mechanisms that drive pulmonary ventilation are atmospheric pressure (Patm); the air pressure within the alveoli, called intra-alveolar pressure (Palv); and the pressure within the pleural cavity, called intrapleural pressure (Pip).