Introduction

E ʻai i ka mea i loaʻa

What you have, eat

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the different types of simple and complex carbohydrates

- Describe the process of carbohydrate digestion and absorption

- Describe the functions of carbohydrates in the body

- Describe the body’s carbohydrate needs and how personal choices can lead to health benefits or consequences

Throughout history, carbohydrates have and continue to be a major source of people’s diets worldwide. In ancient Hawai‘i the Hawaiians obtained the majority of their calories from carbohydrate rich plants like the ‘uala (sweet potato), ulu (breadfruit) and kalo (taro). For example, mashed kalo or poi was a staple to meals for Hawaiians. Research suggests that almost 78 percent of the diet was made up of these fiber rich carbohydrate foods.[1]

Carbohydrates are the perfect nutrient to meet your body’s nutritional needs. They nourish your brain and nervous system, provide energy to all of your cells when within proper caloric limits, and help keep your body fit and lean. Specifically, digestible carbohydrates provide bulk in foods, vitamins, and minerals, while indigestible carbohydrates provide a good amount of fiber with a host of other health benefits.

Plants synthesize the fast-releasing carbohydrate, glucose, from carbon dioxide in the air and water, and by harnessing the sun’s energy. Recall that plants convert the energy in sunlight to chemical energy in the molecule, glucose. Plants use glucose to make other larger, more slow-releasing carbohydrates. When we eat plants we harvest the energy of glucose to support life’s processes.

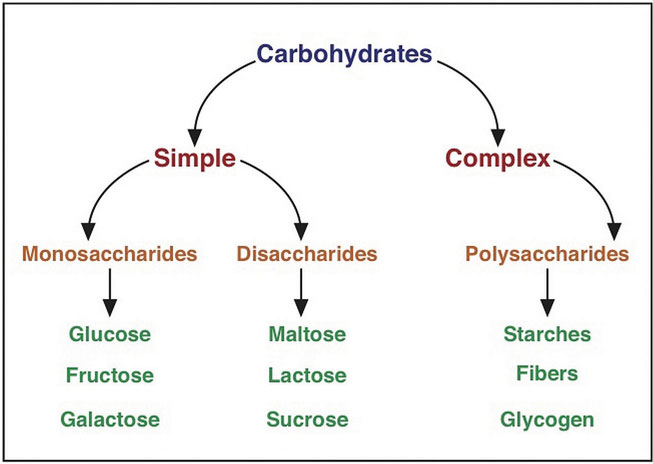

Figure 4.1 Carbohydrate Classification Scheme

Carbohydrates are a group of organic compounds containing a ratio of one carbon atom to two hydrogen atoms to one oxygen atom. Basically, they are hydrated carbons. The word “carbo” means carbon and “hydrate” means water. Glucose, the most abundant carbohydrate in the human body, has six carbon atoms, twelve hydrogen atoms, and six oxygen atoms. The chemical formula for glucose is written as C6H12O6. Synonymous with the term carbohydrate is the Greek word “saccharide,” which means sugar. The simplest unit of a carbohydrate is a monosaccharide. Carbohydrates are broadly classified into two subgroups, simple (“fast-releasing”) and complex (“slow-releasing”). Simple carbohydrates are further grouped into the monosaccharides and disaccharides. Complex carbohydrates are long chains of monosaccharides.

Simple/Fast-Releasing Carbohydrates

Simple carbohydrates are also known more simply as “sugars” and are grouped as either monosaccharides or disaccharides. Monosaccharides include glucose, fructose, and galactose, and the disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose.

Simple carbohydrates stimulate the sweetness taste sensation, which is the most sensitive of all taste sensations. Even extremely low concentrations of sugars in foods will stimulate the sweetness taste sensation. Sweetness varies between the different carbohydrate types—some are much sweeter than others. Fructose is the top naturally-occurring sugar in sweetness value.

Monosaccharides

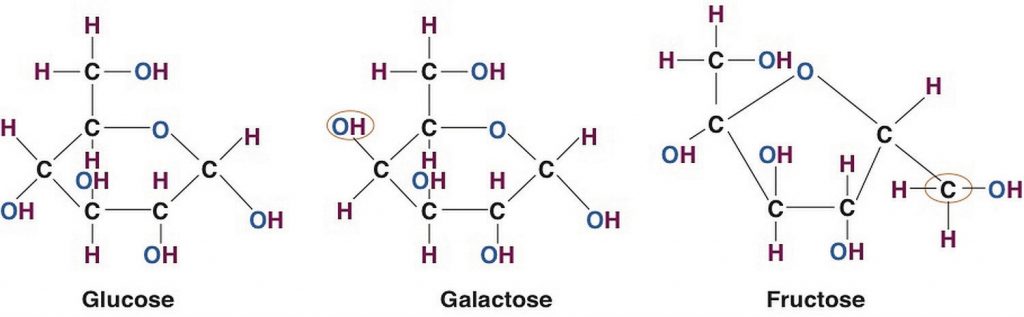

For all organisms from bacteria to plants to animals, glucose is the preferred fuel source. The brain is completely dependent on glucose as its energy source (except during extreme starvation conditions). The monosaccharide galactose differs from glucose only in that a hydroxyl (−OH) group faces in a different direction on the number four carbon (Figure 4.2 “Structures of the Three Most Common Monosaccharides: Glucose, Galactose, and Fructose”). This small structural alteration causes galactose to be less stable than glucose. As a result, the liver rapidly converts it to glucose. Most absorbed galactose is utilized for energy production in cells after its conversion to glucose. (Galactose is one of two simple sugars that are bound together to make up the sugar found in milk. It is later freed during the digestion process.)

Fructose also has the same chemical formula as glucose but differs in its chemical structure, as the ring structure contains only five carbons and not six. Fructose, in contrast to glucose, is not an energy source for other cells in the body. Mostly found in fruits, honey, and sugarcane, fructose is one of the most common monosaccharides in nature. It is also found in soft drinks, cereals, and other products sweetened with high fructose corn syrup.

Figure 4.2 Structures of the Three Most Common Monosaccharides: Glucose, Galactose, and Fructose

Pentoses are less common monosaccharides which have only five carbons and not six. The pentoses are abundant in the nucleic acids RNA and DNA, and also as components of fiber.

Lastly, there are the sugar alcohols, which are industrially synthesized derivatives of monosaccharides. Some examples of sugar alcohols are sorbitol, xylitol, and glycerol. (Xylitol is similar in sweetness as table sugar). Sugar alcohols are often used in place of table sugar to sweeten foods as they are incompletely digested and absorbed, and therefore less caloric. The bacteria in your mouth opposes them, hence sugar alcohols do not cause tooth decay. Interestingly, the sensation of “coolness” that occurs when chewing gum that contains sugar alcohols comes from them dissolving in the mouth, a chemical reaction that requires heat from the inside of the mouth.

Disaccharides

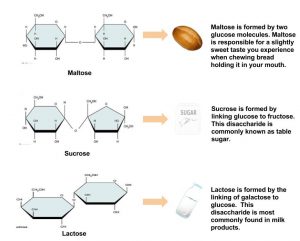

Disaccharides are composed of pairs of two monosaccharides linked together. Disaccharides include sucrose, lactose, and maltose. All of the disaccharides contain at least one glucose molecule.

Sucrose, which contains both glucose and fructose molecules, is otherwise known as table sugar. Sucrose is also found in many fruits and vegetables, and at high concentrations in sugar beets and sugarcane, which are used to make table sugar. Lactose, which is commonly known as milk sugar, is composed of one glucose unit and one galactose unit. Lactose is prevalent in dairy products such as milk, yogurt, and cheese. Maltose consists of two glucose molecules bonded together. It is a common breakdown product of plant starches and is rarely found in foods as a disaccharide.

Figure 4.3 The Most Common Disaccharides

Complex/Slow-Releasing Carbohydrates

Complex carbohydrates are polysaccharides, long chains of monosaccharides that may be branched or not branched. There are two main groups of polysaccharides: starches and fibers.

Starches

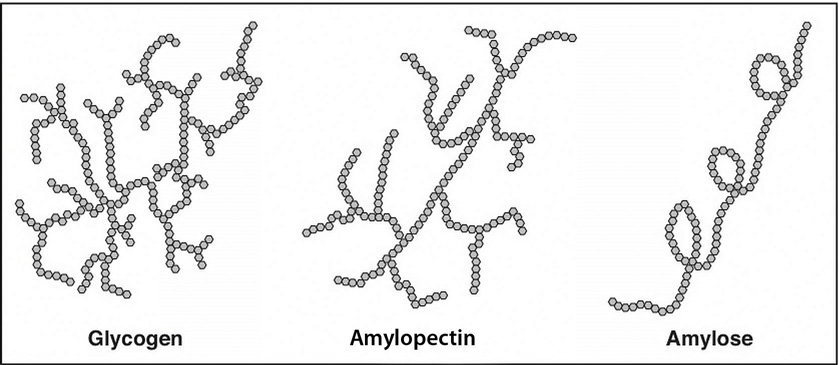

Starch molecules are found in abundance in grains, legumes, and root vegetables, such as potatoes. Amylose, a plant starch, is a linear chain containing hundreds of glucose units. Amylopectin, another plant starch, is a branched chain containing thousands of glucose units. These large starch molecules form crystals and are the energy-storing molecules of plants. These two starch molecules (amylose and amylopectin) are contained together in foods, but the smaller one, amylose, is less abundant. Eating raw foods containing starches provides very little energy as the digestive system has a hard time breaking them down. Cooking breaks down the crystal structure of starches, making them much easier to break down in the human body. The starches that remain intact throughout digestion are called resistant starches. Bacteria in the gut can break some of these down and may benefit gastrointestinal health. Isolated and modified starches are used widely in the food industry and during cooking as food thickeners.

Figure 4.4 Structures of the Plant Starches and Glycogen

Humans and animals store glucose energy from starches in the form of the very large molecule, glycogen. It has many branches that allow it to break down quickly when energy is needed by cells in the body. It is predominantly found in liver and muscle tissue in animals.

Dietary Fibers

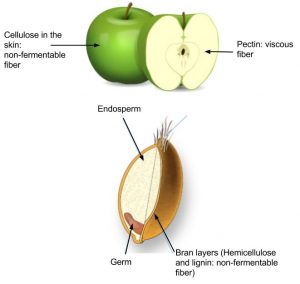

Dietary fibers are polysaccharides that are highly branched and cross-linked. Some dietary fibers are pectin, gums, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Lignin, however, is not composed of carbohydrate units. Humans do not produce the enzymes that can break down dietary fiber; however, bacteria in the large intestine (colon) do. Dietary fibers are very beneficial to our health. The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee states that there is enough scientific evidence to support that diets high in fiber reduce the risk for obesity and diabetes, which are primary risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[2]

Dietary fiber is categorized as either water-soluble or insoluble. Some examples of soluble fibers are inulin, pectin, and guar gum and they are found in peas, beans, oats, barley, and rye. Cellulose and lignin are insoluble fibers and a few dietary sources of them are whole-grain foods, flax, cauliflower, and avocados. Cellulose is the most abundant fiber in plants, making up the cell walls and providing structure. Soluble fibers are more easily accessible to bacterial enzymes in the large intestine so they can be broken down to a greater extent than insoluble fibers, but even some breakdown of cellulose and other insoluble fibers occurs.

The last class of fiber is functional fiber. Functional fibers have been added to foods and have been shown to provide health benefits to humans. Functional fibers may be extracted from plants and purified or synthetically made. An example of a functional fiber is psyllium-seed husk. Scientific studies show that consuming psyllium-seed husk reduces blood-cholesterol levels and this health claim has been approved by the FDA. Total dietary fiber intake is the sum of dietary fiber and functional fiber consumed.

Figure 4.5 Dietary Fiber

- Fujita R, Braun KL, Hughes CK. The traditional Hawaiian diet: a review of the literature. Pacific Health Dialog. 2004; 11(2). http://pacifichealthdialog.org.fj/Volume2011/no2/PHD1120220p2162022120Yamada20orig.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2017. ↵

- US Department of Agriculture. Part D. Section 5: Carbohydrates. In Report of the DGAC on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/DGAC/Report/D-5-Carbohydrates.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2011. ↵