10.18 Tourism in 20th Century Canada

Michael Dawson, Department of History, St. Thomas University

Mountains, lakes, totem poles, Mounties, moose, and a certain house said to have been inhabited by Anne of Green Gables: what do these items all have in common? They have all become staples of Canadian guide books and tourist itineraries.

Of course, sightseeing did not begin in the 20th century. Canada (and British North America before it) had long been a popular destination for travellers keen to experience its natural wonders — and pursue its animal life in the hopes of demonstrating their skill and vigour in killing it. But the scope and scale of tourism in Canada expanded dramatically over the course of the 20th century.

A number of factors facilitated this expansion.

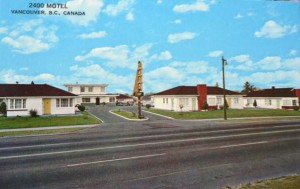

First, technological advances played an important role as railways, roadways, and eventually air travel, dramatically reduced travel times and encouraged visitors to embark upon more ambitious vacations. The invention of the automobile was particularly transformative. Although an automobile was a rare sight in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century, there were over 1 million cars traversing the country’s roads by the end of the 1920s.[1] Gas stations, motels, and diners quickly emerged to service automobile-propelled travellers.

Second, a relatively sustained period of economic growth from the late 1940s to the early 1970s ensured that Canadians and international visitors possessed disposable income to spend on leisure travel.

Third, shifting attitudes toward leisure (from something to be mistrusted and frowned upon to something to be embraced and celebrated) produced a social transformation that facilitated the expansion of Canada’s tourism industry. Canadians and international visitors thus secured increased opportunities to tour the country over the course of the 20th century. But governments, too, played an important role. And the timing of government intervention in the tourist industry is an important part of the story.

In the first three decades of the century, civic organizations and provincial authorities endeavoured to attract visitors to their locales. Some of these bodies hoped that these visitors would return to settle as investors who would bring agricultural and industrial wealth to their local communities. Others focused more directly on the money that these visitors spent in the towns they visited and tried to maximize their immediate, short-term, economic impact. The economic dislocation engendered by the Depression encouraged tourism promoters to focus their efforts even more intently on maximizing tourists’ expenditures. At a time when jobs were scarce and retailers were desperate to sell their wares, many observers argued, it made sense to encourage outsiders, especially Americans, to visit Canadian communities, for in doing so they would be injecting outside money into local economies.[2]

Pursuing this aim, many argued, required a coordinated and efficient campaign — and thus the involvement of the federal government. In response, Ottawa created the Canadian Travel Bureau in 1934. Tasked with expanding and modernizing the nation’s tourist industry, the bureau offered advice to Canadian entrepreneurs keen to profit from tourism, embarked upon hospitality campaigns that implored Canadians to treat visitors nicely, and orchestrated publicity campaigns that aimed to lure tourists (especially Americans) to visit Canada.[3]

Today, tourism plays a central role in Canada’s economy. A recent estimate suggests that tourism is responsible, directly or indirectly, for almost 1 in 10 Canadian jobs.[4] This development did not happen overnight. It was, instead, the product of important technological, economic, and social transformations over the course of the 20th century that were, in turn, facilitated by consumer demand, entrepreneurial initiatives, and government support and coordination.

Key Points

- Tourism advanced in the modern era, helped along by improved modes of travel that included automobiles and aircraft.

- Increased travel brought in its wake a service sector that provided fuel, food, and lodgings, as well as tourist destinations.

- Although there were signs of growth in this sector before 1945, after WWII it increased dramatically thanks to greater disposable wealth in the population and more leisure time.

- The involvement of government in the promotion of tourism from the 1930s established the industry as a credible and lucrative source of incomes and jobs. Along with the technological, social, and economic transformations that enabled the tourism phenomenon to occur, the expansion of the modern, interventionist state played a role.

Attributions

Figure 10.44

DC-3A United Air Lines NC 16071 by James Crookall is in the public domain.

Figure 10.45

2400 Motel is in the pubic domain.

- “In Search of the Canadian Car,”accessed 8 September 2015 http://www.canadiancar.technomuses.ca/eng/frise_chronologique-timeline/1920/ . This was a North American phenomenon. See, for example, John A. Jakle, The Tourist: Travel in Twentieth-Century North America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985), Chapter 7. ↵

- On these competing yet overlapping rationales for tourism promotion campaigns, see Michael Dawson, Selling British Columbia: Tourism and Consumer Culture, 1890-1970 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004), Chapter 2. ↵

- On the formation and development of the Canadian Travel Bureau, see Alisa Apostle, “The Display of a Tourist Nation: Canada in Government Film, 1945-1959,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 12, 1 (2001): 177-97, and Alisa Apostle, “Canada, Vacations Unlimited: The Canadian Government Tourism Industry, 1934-1959," Ph.D. dissertation. Queen’s University, 2003. ↵

- Tourism Industry Association of Canada, “The Canadian Tourism Industry: A Special Report” (Fall 2012), 7, accessed 8 September 2015 http://tiac.travel/_Library/documents/The_Canadian_Tourism_Industry_-_A_Special_Report_Web_Optimized_.pdf . ↵