10.14 A Culture under Siege?

Even as modern styles were stirring the pot of creativity and innovation in the first three decades of the century, censorious clouds were gathering. The fear of the modern was expressed in antimodernist ways and through modern political movements that might, for example, admire scientific progress while simultaneously decrying the emergence in the 1920s of the modern woman.

The Motion Picture Production Code (1930) in the United States tamed Hollywood movies so that popular culture would not be threatened by shifts in popular moral codes. While the Code had no impact on Canadian film-making (such as it was at the time), it impacted the careers of Canadians in Hollywood and, of course, Canadians experienced its effects whenever they visited a cinema.

This was the case, in part, because of the Americanization of Canadian culture. The movement of goods and ideas never had much respect for the boundary lines between British North America and the United States, and the 20th century border was only more porous. Radio — and, later, television — signals swept back and forth across the international frontier unimpeded. American listeners in the northern states picked up the few radio stations producing signals in Canada, while Canadian audiences dialled in to programming that originated, principally, in New York. It was then relayed through networks of private broadcasters to cities like Bangor, Duluth, or Spokane from whence the AM waves worked their way into neighbouring provinces. Some American programming was so popular in Canada that Canadian private stations carried the shows themselves. In many instances, American radio station owners simply bought up private broadcasters in Canada and thus extended their reach.

Radio and TV Broadcasting

By Norm Fennema, Department of History, University of Victoria

As in the United States, radio broadcasting in Canada began in the early 1920s. Because radio use began with mariners, licenses were initially available from the department of Marine and Fisheries for any interested party, with payment of a $25.00 fee. By the mid 1920s, upwards of 30 commercial broadcast licensees — often churches or electrical equipment businesses — operated limited daytime programming in major centres such as Toronto and Montreal.

The impetus for a federal role grew in tandem with the growing availability and popularity of American programming and the apparent chaos of the American commercial system. The formation in 1922 of the British Broadcasting Corporation — an early model of public ownership — seemed to hold the promise of aligning the broadcasting spectrum with its nation building potential. Action was hastened by a national controversy over the cancellation of broadcasting rights of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, operators of Canada’s first and only national network. An ensuing parliamentary firestorm was quelled by the government’s announcement of a Royal Commission on radio broadcasting — the first of many.

The recommendation of the Aird Commission, named for the commission president, that “broadcasting…be placed on a basis of public service and that the stations providing a service of this kind should be owned and operated by one national company” was finally realized in the passage of the 1932 Broadcasting Act, by which the Canadian Radio-Broadcasting Commission came into being.[1] A major victory in one of the hardest fought advocacy campaigns in Canadian history, the battle to realize the Commission’s vision was led by the indomitable patriot, socialist, and anti-American nationalist Graham Spry (1900-1983).[2] Mandated to regulate the existing commercial stations as their operations were being phased out, the new public broadcaster formed an East-West system, partly through appropriation of the Canadian National Railway Radio network, which included a French language service. Retooled as a Crown corporation in 1936, the rechristened Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was hamstrung by chronic underfunding and the Depression.[3] The original goal of a single public system was also contested by commercial station owners through the Canadian Association of Broadcasters (CAB), whose lobbying efforts initiated a battle that is played out to this day with the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting — successor to Spry’s Canadian Radio League. The result was a hybrid system of public and private broadcasting, with the public service continually mandated to provide “a wide range of programming that informs, enlightens and entertains” and one that “should be predominantly Canadian, serve the needs of the regions, be in English and in French, and be available throughout Canada.”[4] Nationally popular programming such as Hockey Night in Canada clearly fulfilled this mandate, while the French language Radio Canada helped engender a renewed sense of Québecois identity.

Reinjection of a nationalist raison d’être for broadcasting came in the context of renewed support for bilingualism and the advancement of multiculturalism in the later 1960s. This resulted in a mandated minimum of 60% Canadian content on television and 30% on radio for both systems. While leaders in news and information programming, the much greater costs of television (20 times that of radio) meant CBC entertainment and dramatic programming tended to compete poorly against American offerings.

The CBC remains an important national institution, though dwarfed in size by the commercial system, still without a guaranteed funding formula, and continually subjected to government cutbacks. Long-running programs such as David Suzuki’s The Nature of Things (which began under Donald Ivey in 1960) and The National are Canadian staples, and despite its loss of Hockey Night in Canada to Rogers Communications in 2014, the network retains millions of viewers and experiences annual growth in online traffic.

A significant rationale for the existence of a public broadcaster was that it would provide that which a commercial system would not. The Broadcasting Act of 1932 was a declaration of federal sovereignty over the airwaves predicated on a conviction that radio broadcasting, in whatever form it might take, was a prima facie public resource, a view that seems to still be supported by most Canadians.

Hollywood and the North

Cinema could have been different from radio. After all, cinemas were not obliged to show American films; and the cans of motion picture reels, unlike radio programming, could be stopped at the border, if need be. Viewed by not one government in Canada as worthy of investment or control, the American and (secondarily) British film industries found their way into Canadian movie houses unobstructed. The world’s first national film production office, the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau, was established in two stages from 1918 to 1923 and from the start specialized in the news-reel style of film-making for national promotion purposes. Indeed, the first movies made in Canada were overwhelmingly documentaries, some of them immigrant recruitment fodder about life on the plains. Although fictional dramas followed early in the 20th century — including some of the earliest war movies, drawing on the 1660 Battle of Long Sault and the War of 1812 as source material — these were to prove exceptions to the rule. This early efflorescence was soon overwhelmed by American product, which was something the Bureau actively encouraged. The first director of the Bureau, Bernard E. Norrish, was dismissive of the possible success of a Canadian film industry, commenting that Canada “had no more use for a large moving picture studio than Hollywood had for a pulp mill.”[5] Other countries, recognizing the threat posed by Hollywood to their own film artists, imposed quotas; nothing of that order occurred in Canada. Canadian cinemas were made more deluxe — this was the era of the movie palace — so as to make the experience of moviegoing still more escapist than the film’s subject matter. Hollywood might occasionally experiment with Canadian-themed movies involving Mounties (some of them singing), but otherwise the experience of entering a darkened movie house in Canada was much the same as it was in Des Moines, Iowa.

By the late 1930s, there was not much left of the Canadian film business. It was with the nurturing of the documentary tradition in mind that the National Film Board (NFB) was established in 1939. Its mission was almost immediately transformed by the outbreak of war. Still steering clear of fictional drama, the NFB now concentrated on wartime propaganda. After WWII, efforts to build a Canadian film industry continued to fail. The consolidation of the theatre chain system and its place in a vertically integrated Hollywood-based industry meant that the major American studios controlled everything from story-pitch through production and distribution. Under these circumstances, it was astonishingly difficult for a Canadian film to find a Canadian audience. By the late 1940s, the Canadian film industry was another arena in which Canadian cultural sovereignty and health was becoming a matter of some concern to policy makers as well as to artists, entrepreneurs, and social commentators.

The State and Culture in the Cold-War Era

Between them, the Group of Seven founder Lawren Harris and his contemporary and close friend Vincent Massey (1887-1967) delivered the one-two punch of 20th-century Canadian culture. Both men were born in the 19th century and were heirs to strong traditions of individualism and, more importantly, to the Massey-Harris industrial fortune. Harris’ role in the founding and success of the Group of Seven is considered in Section 10.14. It was Massey, however, who would advance the question of what was to be done about Canadian culture as a whole.

Massey played a managerial role at the family firm for a while before being drawn into politics by Mackenzie King. By the mid-1920s — while still in his early 40s — Massey was playing important diplomatic roles for Canada. In 1949, he was tasked by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent with chairing the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences, eponymously known as the Massey Commission.

The Commission reflected growing concern on the part of government about the impact of American culture. Even as Canada was gaining greater autonomy from Britain in constitutional and foreign affairs areas, there was a growing reaction to the influence of the United States. Partly this was spurred on by the growing power of the federal state. WWII had laid down the foundations of a vastly increased bureaucracy and government intervention in the economy as well as in social and educational policy areas. The planning state could, quite naturally, extend its reach to cultural concerns.

The Massey Report, issued in 1951, was both a response to American cultural imperialism and an alarm bell. It legitimated government involvement in cultural institutions, laid out a game plan, and endorsed federal spending on post-secondary education for the first time. The Commissioners drew attention to the paucity of performance venues for the high arts and the unlikelihood of all but a handful of artists earning a living from their craft in Canada. American culture was saturating Canada and talented Canadians were heading south because in the United States they could earn a living in the culture industries. Canadian genius went out with the tide and Disney swept back in.

The Commission’s recommendations resulted in the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957, which stimulated the growth of both literature and research in the humanities and social sciences. This second role was hived off in the 1970s into the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). Leading figures in the Liberal Party were not alone in their belief that Canada’s newly won global prominence at the end of WWII meant that the country should shed some of its outward backwardness and become more refined. They sought to use culture as an instrument of a liberal and humanist nationalism and, conveniently, Americanization served as a nice counterweight — a palpable threat — to the health of Canadian arts and letters. This provided a further justification for Ottawa’s involvement and leadership in the field.

Critics of the Commission have jumped on their nationalism as a narrowing and necessarily proscriptive view of Canada, one that held out little for people who came from cultures other than French and English. It has also been dismissed as “a bunch of stuffy college dons trying to force a good dollop of ‘culchah’ down the throat of a gagging Johnny Canuck.”[6] The Commissioners took pains to reassure Canadians that they had no interest in dictating tastes; at the same time, their instincts ran strongly to high culture and large institutions. New homes for the National Art Gallery and the National Library and Archives (now Library and Archives Canada) were called for and eventually delivered; the NFB was beefed up; and money was made available for a generation of big theatres that would be suitable for symphony orchestras, ballet performances, and serious theatre. The Commission also indirectly encouraged investment and enthusiasm for the arts. The Winnipeg Ballet acquired the modifier “Royal” two years after the Commission, and the Stratford Shakespeare Festival got underway in 1952. Cultural spokespeople in Quebec were, however, particularly critical of the Commission, seeing it as an intrusion on the constitutional space occupied by the provinces. Artists and consumers of art whose tastes were not those of the elites were inevitably disappointed that the Commission had little to offer the culture of working Canadians. Finally, the Commission’s timing was such that it could not grasp fully the implications of the newest medium: television. Finding ways to support Canadian literature, theatre, and humanist education and research was, at the end of the day, an important investment in the development of a distinctive Canadian voice; failing to address the issue of television was like leaving down the drawbridge.

The arrival on the scene of television in the early 1950s added a new technological wrinkle to the communications and entertainment industry, effectively combining the radio industry with the film industry. The old radio giants in the United States – the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) – moved easily into the television market and enjoyed an immediate technological, talent, and distribution advantage over all North American competitors, including the upstart American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). The CBC moved into television with fitful success based on its own national radio infrastructure and the cultivation of teams of writers and performers in both English and French. Early television, however, depended heavily on live performance and this presented enormous challenges in a country as wide as Canada. American broadcasters moved more rapidly into taped/recorded programming, led by ABC. In the nearly twenty years between the first appearance of television and the arrival of cable distribution in the late 1960s, American stations were as easy to access as Canadian broadcasts in all of the large markets. Inevitably the CBC began purchasing taped editions of American programming for broadcasting on their own channels within their own schedules.

The regulation of culture in the late 20th-century music industry is considered in Section 9.15. Canadian television companies faced similar constraints on content and these were met without much enthusiasm or concern for quality. While Québecois audiences were able to sustain locally made, French-language programming, English-Canadian stations competed with expensively produced American dramas and comedies that could be purchased and delivered more cheaply than the price of making something in Canada by Canadians. Some exceptions occurred, including The Littlest Hobo (a Canadianization of Lassie), Quentin Durgens, MP (a political drama), and The Beachcombers (which ran from 1972 to 1990), but most efforts faltered quickly. Some, like the notorious Trouble with Tracy, were ostensibly produced at the lowest possible cost simply to satisfy regulators’ demands for Canadian content. Documentaries and nature programs proved more durable, as did current events programs like W5, which debuted in 1966. Children’s programming proved to be especially successful: both Chez Hélène and The Friendly Giant first appeared in the 1950s and enjoyed very long runs.

These efforts could not, however, stem the tide of American television broadcasting. Even as the Massey Commission’s recommendations were bearing fruit, they were doing so in the face of an increasingly suburbanized population’s infatuation with television. The history of communications, film, and broadcasting in Canada continues to reflect this bias that worked against an indigenous, homegrown creativity comparable to what one finds in other English-speaking countries.

Key Points

- Modern culture was increasingly dominated by electronic media like radio and television, both of which were dominated in North America by manufacturers in the United States.

- As Norm Fennema points out, attempts to regulate and stimulate the production of Canadian radio and visual broadcasting began in the 1930s, with mixed results over the three decades that followed.

- Cinema was not regulated and a branch plant system of American-owned screens in Canada ensured the supremacy of American-produced movies.

- The NFB gave Canadian filmmakers credibility, though principally in the field of documentaries.

- State and elite concerns for the future of Canadian culture and for the threat of Americanization was manifest in several forms, including the Massey Commission.

- The Massey Report led to the creation of a cultural support infrastructure that put arts and academic research funding into a kind of order. The kind of culture favoured by the Commission tended to be highbrow, for which it was criticized.

- Television escaped scrutiny for many years, by which time American programming dominated Canadian television schedules, despite a few rare exceptions.

Attributions

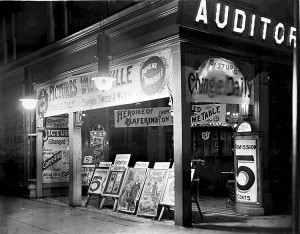

Figure 10.28

Auditorium Theatre in Toronto by EraserGirl is in the public domain.

Figure 10.29

Strand Theatre box office showing advertising for “The Last Chance” by Jack Lindsay is in the public domain. This image is available from City of Vancouver Archives under the reference number CVA 1184-2590.

- Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting, September 1929, in Roger Bird, Documents of Canadian Broadcasting (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988): 52. ↵

- Rose Potvin, Passion and Conviction: The Letters of Graham Spry (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1992), 2, 79. ↵

- Mary Vipond, “The Beginnings of Public Broadcasting in Canada: The CRBC, 1932-36,” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 19, issue 2 (1994): 155. ↵

- Broadcasting Act, subsection 3(1)(m). ↵

- Quoted in “The History of the Canadian Film Industry,” Historica Canada, accessed 10 December 2015, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-history-of-film-in-canada/. ↵

- Paul Litt, The Muses, the Masses, and the Massey Commission (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 6. ↵