10.5 Secular Canada

A key feature of modernity is secularism, the movement away from religious belief most often manifested in the separation of church and state. Anticlericalism in the 19th century took the position that the business of the church was saving souls, not running schools or hospitals, and certainly not influencing governments. In English-speaking Canada, secularism was often a compromise solution to a culture that featured multiple denominations — mainly Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, and Congregationalist — none of which could lay claim to a majority of the population. If there was not one creed that could lead, then none would. This goes some distance to explain the suspicion and, indeed, hostility felt by many Anglo-Protestants to the roles played in Quebec by the Catholic Church.

And yet, as the secular, democratic state was growing in modernist English Canada, so too was the popularity of certain faiths. The consolidation in 1925 of the Methodist, Congregationalist, and (most of) the Presbyterian churches into the United Church of Canada strengthened that wing of Protestantism, making it overnight the third largest denomination in the country. Within the member-denominations of the United Church — and among the Anglicans as well — there were strong Social Gospel elements (see Chapter 7). So, while secularism and modernism called for a separation of church and state, religious activists were often political and social activists as well. While United Church adherents would generally throw their support behind the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, Catholics supported the Liberal Party, and Anglicans the Conservatives.

Organized religion, in short, still played a vital role in political and social life. This was nowhere more apparent than in the rise of evangelical Protestantism in the 20th century (aspects of which are considered in Sections 7.6 and 7.9). Essentially antimodernist in its outlook, sects like the Union Baptists and the Pentecostal Church tended towards a study of and adherence to what they called the “fundamentals” of scripture, and thus became known as fundamentalists. As Tina Block demonstrates in Section 10.6, there came a tipping point in the middle of the 20th century when secularism became a defining feature of Canadian society in tandem with multicultural trends, at which point the antimodernist forces in Christianity and other creeds were marginalized.

And here we have one of those great 20th-century ironies. The Canadian regime most influenced by the Pentecostal Church and fundamentalist values was that of W.A.C. Bennett in British Columbia from 1952 to 1972. Phil “Flying Phil” Gaglardi (1913-1995), a leader of Pentecostalism in the Interior, regularly boasted that he was both a minister of the Crown and a minister of God. Yet no administration embraced modernity more. The potential of technology, engineering, and science to make a bigger and better economy was an article of faith among the BC Socreds (Social Credit Party). One lesson to be drawn from this is that elements of modernity were so pervasive that even the most conservative chapters of Protestantism could not fully resist their influence.

Religious organizations continued through the remainder of the 20th century to exercise an influence that belied their fall from popular favour. No other organization or institution has sufficient influence to partner with the state in the delivery of education, and the norm in Canada is that religious education is subsidized heavily by the provinces (so as to ensure religious schools’ adherence to provincial curricula). Indeed, disenchantment with public schools encouraged a renewed interest in clerical education in the late 20th century. Schools, however, were also the setting for a worsening crisis in credibility: disclosures of abuse of children by clergy and church-sponsored educators in various settings, but most notably at Mount Cashel Orphanage in St. John’s and in many residential schools, poured forth during the 1980s and on and continue to trouble Canadians.

Key Points

- Secularism — the removal of organized religion from the running of the state and social institutions — is one of the dominant features of modernity.

- Anticlericalism in Catholic-dominated Quebec played out differently from anticlericalism in multi-denominational English-Canada.

- Religious activists often took their perspectives and goals into public life in mainstream political organizations.

- Many denominations and faiths responded to modernism with hostility, seeing it as an agenda for their marginalization.

Attributions

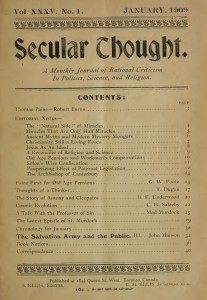

Figure 10.8

Secular Thought Cover Image (Jan. 1909) by J. S. Ellis is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.5 license.