5.5 The Promised Land

Before the Industrial Revolution, working the land was what most people did, in one way or another. And, since it was the norm, it was nothing special.

Then cities took off in earnest, and the cities became not merely bigger versions of their former selves but industrial hives: crowded, dirty, dangerous, unhealthy, and exploitative, and subject to violent economic and political upheavals. Under these circumstances, the land acquired a connotation of relative purity; held up against the cities, the countryside positively glowed with wholesome and godly virtues. Avoiding city life and the prospect of working for someone else became the objective of many Canadians and immigrants. Owning one’s own land and being one’s own boss was highly desirable and it was seen, too, as having a special virtue.

God Made the Country, Man Made the Town

In a 2007 collection of essays on the settlement of the West, several scholars pursue the theme of the promised land. The suffragette, writer, and moralist Nellie McClung saw the West as a place where conditions were good for the raising of Christian-spirited, temperate (that is, free of liquor), and empowered generations — although she experienced disillusion in every regard by the 1920s and 1930s.[1] The leading Social Gospeller of his day (and eventually the founding leader of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation), J. S. Woodsworth, believed that the kingdom of God could be established on Earth and specifically “that the fertile soil of the Canadian prairies nurtured the right conditions for the growth of God’s heavenly kingdom on earth – the Promised Land.…”[2] In this regard, Woodsworth wasn’t too far out of step with Louis Riel’s 1885 millenarian vision of the West as a nurturing refuge for an assortment of religious creeds.[3] This became something of a reality for the Mennonite and Hutterite colonies that erupted on the Prairies and in pockets in southern Ontario and in the Fraser Valley. A similar, though more checkered, experience was shared by the Doukhobors.

Parallels could be drawn, too, with West Coast utopian communities. These appeared in several locations, notably at Ruskin and, somewhat more successfully, at Sointula on Malcolm Island. While these two experiments had ethnic and working-class roots, there were others that tapped into upper-class aspirations, the best example of which is Walhachin, west of Kamloops, where well-to-do English immigrants attempted to rebuild a throwback village lifestyle in 1909, one that included a cricket oval, fox hunts, and a smart hotel which boasted a dress code. Historian Patrick Dunae has written on the widespread cultural, economic, and political impact of this cohort of “gentlemen emigrants” and “remittance men” — second or third sons of money who were unlikely to inherit much if they stayed at home in Britain.[4] There were strong anti-materialist threads in all of these enterprises, as there was in individual homesteading. These were themes that would reappear sporadically in the 20th century in the context of back-to-the-land movements, especially in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Key Points

- Agricultural settlements at the beginning of the 20th century were often associated with virtues and values that were regarded by some as superior to life in the cities.

Attributions

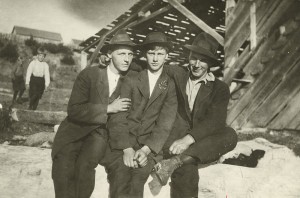

Figure 5.8

View of John Lanquist, Gino Pakkala and Harold Malm Sr. in Sointula, B.C by UBC Library is in the public domain. This image is available from the UBC Library, Fishermen Publishing Society under the digital identifier BC_1532_1373_9.

Figure 5.9

Walhachin Hotel by CindyBo is in the public domain.

- Randi Warne, “Land of the Second Chance: Nellie McClung’s Vision of the Prairie West as Promised Land,” The Prairie West as Promised Land, eds. R. Douglas Francis and Chris Kitzan (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2007): 217-219. ↵

- R. Douglas Francis, “The Kingdom of God on the Prairies: J. S. Woodsworth’s Vision of the Prairie West as Promised Land,” The Prairie West as Promised Land, eds. R. Douglas Francis and Chris Kitzan (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2007): 225. ↵

- Thomas Flanagan, Louis “David” Riel: Prophet of the New World, revised ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 101. ↵

- Patrick Dunae, Gentlemen Emigrants: From the British Public Schools to the Canadian Frontier (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1981). ↵