6.7 The Natural Governing Party: The King Years

Borden departed the prime minister’s office in July 1920, having governed Canada through what is arguably the most dramatic decade in its history. Borden was the author of some of that drama, to be sure, but he never had to defend his record at the polls outside of wartime. He resigned and handed the prime ministership off to Arthur Meighen (1874-1960). Unelected, Meighen held on for 15 months until an election was unavoidable. He lost convincingly to William Lyon Mackenzie King in the dying days of 1921.

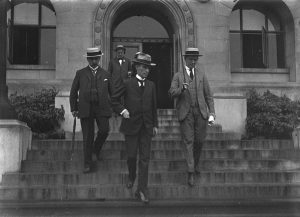

Arthur Meighen

Meighen is one of those politicians caught in the cat’s paw of history. He failed in 1921 because Canadians were tired of Borden and the Tory/Union government and its cynical manipulation of the 1917 election, angered by the Military Service Bill (of which Meighen was the author), upset about the mess made at Winnipeg in 1919 (in which Meighen played a prominent role as minister of justice and the man behind the anti-sedition amendment to the Criminal Code, Section 98), and peeved about prohibition. Meighen himself was barely considered by an electorate eager for change. In 1926 he was thrown into the job in the least defensible way and was thereafter (unfairly) associated in the public mind with an attempt to subvert the democratic process. He is, however, worth pondering for a moment.

Meighen was the first Canadian prime minister born in the post-Confederation period. He is the only one, as well, to have come from a farming background, a remarkable fact for what was until 1921 a mostly rural country. Meighen was raised and educated in Ontario and was part of that great westward migration to Manitoba. He was as representative as anyone of the extent to which Ontarian legal, professional, educational, and gendered certainties were being transplanted onto the plains. He is the only PM elected from Manitoba (his riding was Portage la Prairie) and the first westerner to hold the job. He was bright, articulate, a sharp and witty debater, and absolutely loathed by Mackenzie King — a feeling that was returned with interest. The two men, when young and both attending the University of Toronto, knew and disliked each other. This did not change. As Meighen’s biographer writes, “Meighen was a dogged logician and orator who believed in straight talk. [King] was given to wordy platitudes and endless consultations. Their temperaments clashed, and so did their ambitions.”[1]

King and Meighen, side by side, offer an insight into how much and how little had changed in Canadian politics. Meighen came from modest roots and was a farm boy. King’s grandfather on his mother’s side was William Lyon Mackenzie, one-time mayor of Toronto, a radical-reform politician and newspaperman, a full-time thorn in the side of the Upper Canadian establishment (aka: the Family Compact), a sometime rabble-rouser, and a prominent leader of the 1837-38 Rebellion. In this sense, and perhaps ironically, it was King who had the political pedigree. Meighen, however, carried the banner of the old political elites: he was a small-c conservative, an advocate for pre-War values and social relations, and a man who kept wearing starched high collars long after modernists like King disavowed them outside of formal occasions. Meighen was often decisive, sometimes to his disadvantage. During the Chanak (or Çanak) Crisis of 1922, he urged the King government to recall parliament and ready the troops in aid of Britain; King was in no rush to do so and the conflict was over before it had a chance to divide French and English Canadians.

The careers of King and Meighen, however, seem almost intertwined. In fact, were it not for Meighen, King — never a particularly sympathetic character — might not have gained, let alone held on to power. Meighen was the ninth prime minister, all but two of whom were Conservatives. Over 54 years, the Liberals had formed the government for only 20. Laurier said that the 20th century would belong to Canada; in point of fact, it mostly belonged to the Liberal Party. But only after the Conservatives made a gift of it to King.

Meighen campaigned in 1921 at the head of what was called the National Liberal and Conservative Party, essentially the remnants of Borden’s coalition Union Government. Rather than make a break with the divisive past — that is, a scandalous 1917 election rigged to ensure the success of conscription and thus opening a chasm between Quebec and the Conservative Party — Meighen held on to the old symbols of the Union regime. He worsened his chances by confirming his commitment to a return of the National Policy, including the tariffs. Canadian farmers were almost universally opposed and many of them broke with the Tory Party to form the Progressive Party (see Section 7.9). Frozen out in Quebec, the Conservatives lost much of rural Ontario as well and the Prairies. The Liberals under King, however, did not romp to power. The Conservatives took 49 seats, the Progressives won 58 (one of which was claimed by Agnes Macphail, the first woman in Parliament), and the Progressives’ less well-organized allies took another 10, leaving the Liberals with 118 seats — the barest of majorities. With one Liberal Member of Parliament in the Speaker’s Chair, the two sides of the House were balanced.

By all rights, the Progressives should have formed the Official Opposition. Their philosophy, however, included a critique of the binaries of parliament. They sought to work with, rather than against. This provided the third party leader, Meighen, with a chance to lead Her Majesty’s Official Opposition.

King and Commons

Putting the war behind the nation, binding up its wounds, and reducing the levels of animosity between the English and French, nativist Canadians and ethnic immigrants, labour and capital were King’s priorities. Like Laurier, under whom he had served as Minister of Labour, King sought a path of compromise. This was especially challenging when it came to the issue of the tariff. Opposed by farmers, it was still embraced by manufacturers and urbanites in industrial cities. King lowered it, but not too much. Indeed, his first administration was marked by a lack of drama at home and abroad. The 1923 Imperial Conference gave King a chance to reiterate the case for autonomous Dominions within what was now called the British Commonwealth of Nations. The economy was recovering; grain was once again flowing off the Prairies and for this King could claim little credit. His skills at building political bridges across the country were noteworthy but the electorate of 1925 evidently did not care. The Conservatives under Meighen, rather remarkably, won 115 seats and the Liberals only 100. Just as Meighen had lost his own Portage La Prairie seat in 1921, King lost his in 1925 and had to scramble to find a safe constituency and a compliant Liberal MP who would make way for him. It was very nearly a disaster for the Liberals. The Progressives were once again the wildcard; they were not yet a spent force but they held on to 22 seats. Meighen expected to form a government but King moved quickly to confirm Progressive support of a Liberal minority.

Predictably, Meighen and the Tories were outraged. When a bribery scandal suddenly threatened the Liberal government, King acted with uncharacteristic decisiveness. Rather than wait for a vote of censure over the issue of bribery and smuggling, he consulted with the Governor-General — the former Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng (the leader of the victory at Vimy) — and asked for dissolution of the House of Commons and a new election. Byng declined the request and King resigned as PM, allowing Meighen to step into the vacuum. This led to a constitutional crisis in which King characterized Byng’s constitutional ruling as the meddling of a non-elected official appointed by a foreign power. Three days into Meighen’s administration a vote of non-confidence was called and the combined force of Liberals and Progressives defeated the government. Byng promptly called an election. This unusual interlude has been known ever since as the King-Byng Affair or, better still, the King-Byng Thing and has been a reference point for every Governor-General on election night when the possibility of a minority government looms at the polls.

King’s Liberals were returned and, with the support of ten Progressives, formed a majority government. The four years that followed would see an extension of Canada’s sovereignty at the 1926 Imperial Conference, recognized formally in the Balfour Declaration. A rising economy improved the government’s fiscal position so much so that the Canadian National Railway — a unified system of smaller railways brought together and nationalized under the Borden government — was at last showing a profit. King’s long-term interest in social welfare measures was manifest in the first old age pension, introduced shortly after the election. But King’s administration was less about “big government” than government as an arbitrator, a third-party, or fair broker. It was how King ran cabinet meetings and how he ran the country. He even reduced taxes, thus spending down the surplus that Ottawa had accumulated.

His timing and his reading of the economic situation could hardly have been worse. In 1928 grain prices began a long-term fall and the next year the stock market crashed. Going into 1930 — and due for an election — King maintained that the economy was merely adjusting a bit and he advocated inaction (see Section 8.5). Canadians disagreed and voted the Liberals out of office.

A Pyrrhic Victory

King’s defeat was comprehensive. Only Saskatchewan and Quebec returned more Liberals than Tories but even in Quebec the Conservatives won 24 seats. Looking at the political history of Canada from 1867-1930 one could argue that the Conservatives were the more successful party; the party of Macdonald and Cartier was still the natural governing party of Canada. The Depression, however, would destroy the Tories for more than a generation.

Richard Bedford Bennett (1870-1947) served in Borden’s government, was briefly Meighen’s minister of justice, and then failed to win a seat in 1921. In the brief Tory interlude of 1926, Bennett was the minister of finance. In 1927 he was party leader. Like Meighen, he represented a prairie constituency: Calgary West. Bennett’s personal wealth was substantial and he was believed to be financially independent by 1909. Like Meighen, he was a tough debater but his appeal to Canadian voters was his own prosperity. Playing the role of the hard-nosed master of high finance and industry, it meant something when Bennett promised to “blast a way into the markets” that were closed to Canadian goods by tariffs. In the midst of a global depression, however, there were few markets into which one might blast.

Like King, Bennett was inclined to think that the Depression might just go away on its own. By 1933, when things were at an all-time low, he began to build a response. This included relief camps for the unemployed (highly unpopular and condemned by the public as “slave camps”) and the promise of some major social reforms that included unemployment insurance, health insurance, and income-based personal taxes. Like most politicians who were in power in 1933, however, Bennett’s time in office was to be cut short. He lacked imagination and the political will to make changes in what was, to be fair, the worst economic crisis in the country’s history. Bennett was nevertheless reviled, a lightning rod for the nation’s discontent. Disgusted, he soldiered on as Opposition Leader until 1938 when he returned to his native England and retired with a viscountcy. Bennett’s unpopularity was such that no subsequent Canadian leader would accept a knighthood.

In 1935 the Conservatives were once again swept from power, still stigmatized in Quebec as the party of conscription and Riel’s gallows. Now they were damned in western Canada, as well, as the party of the dust bowl.

King and Chaos

King’s economic and social policies were hardly better than Bennett’s when it came to spending the country’s way out of crisis. A slight up-tick in the economy after 1935 reversed in 1937 so there was little confidence that the corner had truly been turned. Elected on the slogan “King or Chaos,” the Liberals offered only a few new ideas that were meant to cushion the effects of the Depression. A National Housing Act was introduced but social policies were otherwise missing. The principal legacy of this administration was the creation of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in 1936 and the National Film Board (NFB) in 1939 (see Section 10.14). The beginnings of a national airline were laid out in Trans-Canada Airlines in 1937, which would eventually become Air Canada.

As war in Europe approached, King’s inclination was to refuse to make commitments to Britain. An attack on Britain would be defended, but British engagement in a continental war would be not be enjoined by Canadians. Like many of his contemporaries, King underestimated the ambitions of Führer und Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist government. What is more, King was inclined to see Hitler as a kind of romantic and messianic figure with a spiritual mission. This reflected King’s own rather unusual spiritual outlook (see Section 9.5). King had missed the Great War by dint of working as a consultant to the Rockefeller family in New York and director of the Rockefeller Foundation from 1914-1918. During that time, he polished and formalized his conception of the state as a third party in disputes between labour and capital, ideas that he would take into inter-provincial diplomacy and, on the eve of the Second World War, into talks between Britain and the United States. His revulsion for conflict would not, however, protect him from the struggle that was unfolding globally.

Key Points

- The Meighen and King years demonstrate some of the constitutional liabilities of the Canadian parliamentary system.

- Despite pronounced differences during election campaigns, the Liberal and Conservative governments of the interwar years had similar records when it came to social policy.

- Canada’s increased autonomy within the British Empire was welcomed by King.

- Meighen’s failures in the 1920s, coupled with Bennett’s in the 1930s, led to a long run of Liberal governments.

Attributions

Figure 6.14

Premier Arthur Meighen’s inspection Toronto, Ont. Aug. 13, 1920 (Online MIKAN no.3657723) by Toronto Harbour Commissioners / Library and Archives Canada / PA-097014 is in the public domain.

Figure 6.15

Group photo of delegates attending the Imperial Conference, 10 Downing Street (Online MIKAN no.3199796) by Library and Archives Canada / PA-138871 is in the public domain.

- Larry A. Glassford, “MEIGHEN, ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed 10 November 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meighen_arthur_18E.html. ↵