11.9 The Aqueduct and Colonialism

Adele Perry, Department of History, University of Manitoba

Located at the forks of two major rivers and prone to flooding, the city of Winnipeg often seems awash in water, but an adequate supply of clean drinking water has been a continual problem for the city from its earliest days as the Red River Settlement to its incorporation as a city in 1874 to the present day. In his classic Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914 (1977), Alan Artibise explains how in the last decades of the 19th century, Winnipeg experimented with private companies and public water supply operations. They filtered river water and dug artesian wells, but still had to deal with problems like “hard” water (with a high mineral content), inadequate supply, and, more pressingly, annual outbreaks of typhoid. 1904 was especially bad: 1,276 people, or a little over 5% of 67,300 Winnipeggers, were diagnosed with typhoid.

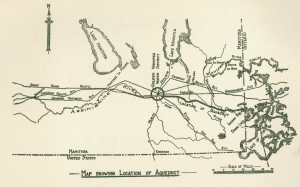

By 1913 the ambitious settler city had decided to address its enduring problems with the water supply by building an aqueduct to transport water from Shoal Lake. Located about 150 kilometers east, Shoal Lake straddles the borders of Ontario and Manitoba, and is within Anishinaabe territory, which is covered by the provisions and promises of Treaty 3, signed in 1873. Supporters of the Shoal Lake Aqueduct were well aware of just how expensive and ambitious the plan was, and argued that the estimated cost of $13.5 million would be well worth it to secure Winnipeg’s human and economic growth.

What this plan might mean for the Anishinaabe communities at Shoal Lake rarely entered into the conversations about what the Aqueduct could do for the mainly settler city of Winnipeg. In 1914 the Federal Government used its enormous powers under the Indian Act, first passed in 1876, to sell approximately 3,000 acres of land belonging to Shoal Lake 40 Reserve to the Greater Winnipeg Water District (GWWD) for the sum of $1,500. In an effort to separate “dark” water from the more palatable water destined for the city, the GWWD then built a canal and a dyke, which effectively made the community of Shoal Lake 40 an artificial island.

Shoal Lake water first flowed in Winnipeg’s water mains in 1919, less than half a year after the armistice of the Great War and a few months before a General Strike would rock the prairie city. The project carried an enormous price tag: it cost $17 million at the time, which translates to about $229,861,702 in 2016 terms. The Shoal Lake Aqueduct project involved the building of a railroad, telephone lines, and tunnelling under multiple rivers, and employed as many as 2,000 men at one time — all during the labour shortages of World War 1. The Aqueduct has served the city of Winnipeg well and continues to supply the city with its drinking water.

It did not take long for Winnipeggers to begin celebrating the Aqueduct as a triumph of engineering and public-minded policy. It would take much, much longer and an enormous amount of activism and advocacy from Indigenous communities for awareness to grow with respect to what the Aqueduct cost the Anishinaabe communities of Shoal Lake. Surrounded by Winnipeg’s water supply, Shoal Lake 40 nevertheless lacks a reliable source of fresh water, and the community has been on a boil water advisory since 1998. (They are not alone: as of the summer of 2015, there were about 175 drinking water advisories in Reserves across Canada.) Also, the approximately 250 people of Shoal Lake 40 lack a year-round way of coming and going from the community, and as a result, have poor waste removal, emergency services, and postal services. During the winter, they use an ice road across water, but for a few weeks every fall and spring, they face the danger of travel across thinning and uncertain ice.

The fact that the community of Shoal Lake 40’s poor water supply and any chances for ameliorating it can be tied directly to the Aqueduct that secured Winnipeg’s water supply tells us a lot about the history of colonialism in modern Canada. The relative prosperity of non-Indigenous people in 20th century Canada has come at the expense — sometimes general and sometimes very specific — of Indigenous people. Alongside the histories of World War 1, the Winnipeg General Strike, and the provision of municipal services in Winnipeg and across Canada, we also need to analyze the histories of Indigenous dispossession that undergirded the stories of settler vision, conflict, and triumph.

Key Points

- The ability to undertake large engineering projects in the 20th century recasts colonial relations between Canada and Aboriginal communities like Shoal Lake 40; the issue is not simply the taking of Aboriginal land, but any other resource that is needed by the colonial society. As is the case at Shoal Lake 40, this is very much to the detriment of the colonized people.

Attributions

Figure 11.14

Map Showing Location of Aqueduct (1918) by Wyman Laliberte / Courtesy of University of Manitoba : Archives & Special Collections is used under a CC-BY-2.0 license.