7.6 Social Gospel

Of all the reform movements arising out of the 19th century, arguably none had as extensive a reach as the Social Gospel. Faced with the new realities of urban overcrowding, grueling factory work, and grinding poverty, Christians in North America questioned whether their focus should be on the salvation of the individual or of society as a whole. Conventional wisdom in the mainstream churches had always been that the issue of salvation was entirely a personal matter. Urbanization and industrialization challenged that perspective. Increasingly, clergymen and religious writers were of a mind that the physical environment in which the battle against sin took place was so changed by industrialism that new approaches were necessary. They found a receptive audience in the middle- and working-classes, and produced several generations of political, social, and cultural leaders as a result. The values of the Social Gospel became the fuel behind many political and socio-economic movements in the first century after Confederation, some of which were inevitably contradictory.

From the Pulpit to the Public

Two of the largest and most influential institutions in British North America at the start of the 19th century were the Anglican (or Church of England) and Catholic Churches. Wherever there were Scots, there were Presbyterian churches as well, although this was in fact a number of fractious denominations that only converged around the time of Confederation. Methodists constituted the next most populous sect, and there were significant numbers of Congregationalists in the colonies, particularly in New Brunswick. But the two principal Christian churches — Catholic and Anglican — were head and shoulders above the competition in terms of adherents and political influence. The authority of the Anglicans was part of the very fibre of the Family Compacts in the English-speaking colonies and in anglophone Montreal; Catholicism enjoyed a near monopoly in French-Canada. Both churches were broadly engaged with civil society, providing much of pre-Confederation Canada’s educational, welfare, and healthcare infrastructure. Bishops and Archbishops endeavoured to set much of the moral tone and brokered power between the colonial governors and the secular leadership. Their values were simultaneously very conservative (in the case of Quebec’s Catholic clergy, they were defensively so in the face of Anglo-Protestant hostility) and community-minded.

Much of the history of political struggle in Canada overlaps with the history of sectarian conflict. The Presbyterian and Methodist elements objected to the authority exerted by the Anglicans in what became Ontario; the mid-19th century Reform Party was overwhelmingly drawn from the non-conformist churches, while the Tories were essentially the political wing of the Anglican Church. The situation was similar in most parts of pre-Confederation Canada, although clearly different in Quebec where Anglicans and Presbyterians were allied against Catholics. Sectarian turmoil was not uncommon, and it is important to recall the vigour with which Orange elements attacked the rights — and the bodies — of Catholics in Saint John, Toronto, Red River, and elsewhere in Victorian Canada. This background underlines the extent to which divisions between denominations mattered, emotionally and practically, to Confederation-era Canadians.

As the Dominion of Canada project got underway these relationships evolved and became important in new ways. The Victorian years witnessed the rise of new Christian denominations while some older sects changed their course. It is impossible to imagine these new elements occurring outside of the context of industrialism and other socio-economic disruptions in the Victorian era. The Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists — along with “Low” Anglicans — were already critical of the liturgical and hierarchical qualities (sometimes called “Churchianity” as opposed to Christianity) of the “High” Anglican and Catholic Churches, and the instances where it seemed political leaders were following the Archbishop or even the Pope rather than the electorate. But the influence of evangelicalism was embodied in smaller denominations like the Lutherans and Baptists, in elements within Methodism and Congregationalism (both of which were growing in popularity), and in entirely new churches like the Salvation Army — posed a challenge to the established churches’ view of spiritual redemption and, implicitly, to social relations.

The 19th century evangelicals include profoundly different and distinctive voices and theological viewpoints. Many — the Salvation Army in particular — were very urban in their outlook, and all took the perspective that personal and direct salvation was a possibility. This was a critique of the older churches’ mediation of the relationship between the individual and God. While this brought the individual into sharp focus, it had the almost perverse effect of making the social more obvious. The evangelicals’ view, however, was one of a society made up of individuals (a view that was consistent with the rising tide of democracy), as opposed to one made up of categories and castes. “Evangelical” itself derives etymologically from “good news” — and the good news was that everyone (and thus the whole of society) could be saved.

The infrastructure of the Social Gospel included bricks and mortar as well as personnel. The centre for much of the movement’s development was Wesley College in Winnipeg, a Methodist post-secondary institution established in 1888. The intersection of late-Victorian Methodism — with its redemptive message, culture of outreach, and largely working-class constituency — and the city of Winnipeg — growing at an explosive rate into the capital city of the whole West — was critical to the development of the ideals of the Social Gospel at Wesley College. Salem Bland (1859-1950) moved from central Canada to a professorship at Wesley in 1903, where he nurtured a generation of Social Gospel leaders. These include two founders of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF): James Shaver (J.S.) Woodsworth (1874-1942) and William “Bill” Irvine (1885-1962) (see Section 7.9). Wesley College students, faculty, and graduates played an increasingly vocal role in criticizing the conduct of the Great War, some of them (like Woodsworth) embracing pacificism, others attacking wartime profiteering. They were also active in the events around the Winnipeg General Strike (Section 3.9) and together believed that if revolution was coming, it would be a revolution of religion and the establishment of a new order, with Social Gospel evangelism at its centre.[1]

What this new — and extremely popular, entertaining, and challenging — religious movement discovered, of course, was that salvation was hard work particularly when the sinners in the crosshairs are living their lives in squalor, poverty, addiction, and ignorance. Saving souls was one thing; saving society was another.

Building a Heaven on Earth

The range of projects in which the Social Gospellers engaged was broad but they shared some core elements. Temperance was one, fighting the causes of poverty was another (although methods might differ drastically), and a representative cross-section took an interest in eugenics. In Central and Eastern Canada the focus was heavily on urban squalor and sin, while in the West there was a stronger emphasis on the project of building a new and ideal society from the ground up.

Their approaches combined elements of faith and science, a feature that further distinguished them from the Anglicans and Catholics (although both of the big churches would change in this regard in the 20th century). Sometimes these combinations produced contradictions. The Social Gospel interest in eugenics, for example, arose from an awareness of advances in biological sciences. It might be argued that their commitment to the view that genes (nature) trumped environment (nurture) was inconsistent with their view that the physical world mired the individual in sin. They criticized, as well, the role of the non-evangelical faiths in matters of government, while simultaneously seeking to create a more activist and interventionist state. Regardless of these contradictions, the Social Gospellers constitute the first generation of Christian thinkers to understand sin and redemption through a science lens, and to attempt to resolve it through the further application of science and social innovation.

Social Gospellers were prepared to make full use of the arsenal of modern technology, engineering, and planning. Clean water and well-lit streets were as critical to this project as any Sunday sermon. At the same time, they recast the issues of moral failings from the individual (e.g., drinking or ignorance) to the social (e.g., alcoholism or lack of educational opportunity). As the century closed and a new one began, some of the concerns of the Social Gospellers shifted to questions associated with immigrant communities. Many of the newcomers were neither Protestant nor Catholic and were regarded by some Social Gospellers as a threat in their own right. Education might play a role in assimilating immigrants, but reformers’ suspicion of the Eastern European or Asian Canadian proved hard to shake, and it would provide part of the context for the spread of eugenics across the Social Gospel movement.

Targeting Reform

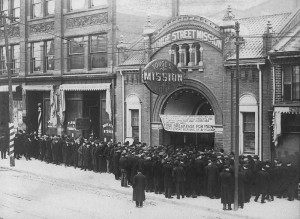

The array of crusades launched by the various branches of the Social Gospel movement included high-level politics and street-level service. Missions and “settlement houses” were established among the urban poor and in Aboriginal communities. The Salvation Army became active in city centres, on reserves, and in the North. Wilfred Grenfell opened his own mission in Labrador, in 1893. Methodists in the 1880s joined with other denominations in establishing residential schools for Aboriginal students (see Sections 11.7, 11.8, 11.9, 11.10, and 11.11); support for these projects came from Social Gospellers who saw them as an instrument of assimilation into an advanced Christian- and Anglo-Canadian culture and also as “schools that met the practical and physical needs of Aboriginal peoples.”[2] The settlement houses were, similarly, located on the boundary between social change and social control: they offered daycare, some schooling, help finding employment, language classes for immigrants, and so on, but they were also centres for transferring and imposing the dominant societies’ moral values to newcomers. It was this combination of targeted Christian good deeds among the poor, the voiceless, and the colonized, the moral regulation of deviant (including alien) behaviour, and efforts to counter the ill effects of capitalism and urban life that characterized most Social Gospel activities.

The Social Gospel Style

Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944) was arguably the most famous Canadian of her time. Born Amie Elizabeth Kennedy in Salford, Ontario, she was influenced by the Salvation Army (still very much a new thing in late Victorian Canada), married at 18, widowed at 19 (while pregnant with her first child), remarried at 22, divorced at 29, married for a third time at 41 years, and divorced again three years later. Her travels across North America matched her tumultuous personal life: she relocated to the United States in her 20s and dedicated her life to evangelizing.

Semple McPherson was a barnstorming preacher who was increasingly associated with the emergent Pentacostal faith. Moving to Los Angeles in 1918 put Semple McPherson at the centre of what was just emerging as America’s West Coast metropolis and film industry capital. Huge and elaborate stage sets were produced for her revivalist meetings, and the level of theatricality in Semple McPherson’s sermons was both astonishing and of the highest quality. Her meetings were attended by as many as 40,000 at their peak, and were often chaotic and fevered; their unpredictable and inventive features influenced other evangelicals and event producers for generations. The most elaborate of her performances were not entirely unlike 1970s and 1980s stadium-venue rock concerts, and the temple she built in Los Angeles owed more to music halls than to cathedrals. Moreover, Semple McPherson crossed media by combining live performances with film and radio broadcasts. She was a superstar before the term was invented.

There was room for only one Aimee Semple McPherson, but the Social Gospel and the evangelical trend both produced her, and was influenced by her. Some of the leading figures in the movement in Canada came from the pulpits, and many learned how to be political and rally speakers from watching and hearing the evangelicals in action. On the Left, J.S. Woodsworth was a Methodist minister and Tommy Douglas (1904-1986) was a Baptist preacher. Both men went on to lead the early CCF as champions for social change. Nellie McClung (1873-1951) was defined by her Social Gospel credo as much as her father’s Methodism; she sat in the Alberta legislature as a Liberal member. Further to the Right, William (“Bible Bill”) Aberhart (1878-1943) was an ardent Baptist who established his own evangelical organization — the Calgary Prophetic Bible Institute — and created the Social Credit Party as a means to achieve greater social equity through financial reforms (see Section 7.9). His successor at both the evangelical and secular level was Ernest Manning (1908-1996), who was raised in a generation that could identify its creed as simply “evangelical.” Manning went on to become one of the most successful politicians (in terms of longevity) in Canadian history, and he was the father of the late 20th century Reform Party leader, Preston Manning (b. 1942). Both Ernest Manning and Aberhart followed Semple McPherson’s pioneering work in radio as a means to reach into rural and urban households alike with social, economic, and political messages. All of these individuals shared in that evangelical, crusading, and urgent approach to modernity that demanded change based on the goal of a Christian moral civilization.

Watch this undated recording by Tommy Douglas on The Cream Separator. Tommy Douglas uses a familiar clergyman’s rhetorical technique, the parable, to deliver a moral lesson that crosses into the political. Many Canadian politicians still attempt to approximate this style, which is rooted in the Social Gospel experience of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Opposition

Mainstream resistance to the Social Gospel message was powerful and persistent. The Anglican and Catholic Churches had their own agendas of social change, but these involved the preservation of social hierarchies, which, the left-wing of the Social Gospel would say, were at the foundation of social injustice. The further to the left some of the Social Gospellers moved, the more likely they were to be associated by their opponents with socialism and communism. In truth, while some of the Social Gospellers found their way toward social democracy, the Christian heart of the movement was a rampart against the secularism of communist movements. Right-wingers, too, fell afoul of the mainstream. When Aberhart attacked the banking system and attempted to dilute the national currency (with what was derided as “funny money”), he was twisting the tail of old money in Montreal and Toronto. (His conservative evangelicalism and suspicion of international money interests also drew a charge of anti-Semitism.)

The very populism of the Social Gospel — its mass appeal and its folksy, inclusive style — was dismissed by Liberals and Conservatives as the work of “teachers and preachers.” Calls for fair treatment of labour organizations, relief to farmers caught by rising costs and falling farm produce prices at the end of the Great War, and money support for the unemployed in the 1930s were ignored by the old parties. Their intransigence across the first four decades of the 20th century cost them significant support and resulted in the creation of the United Farmers parties across English-speaking Canada, several of which formed governments at the provincial level. The Progressive Party followed, as did the CCF and Social Credit (see Section 7.9).

These Social Gospel experiments in politics also drew fire from the Left. Socialist and communist organizations were suspicious and critical of the Christian agenda of the Social Gospel, regarding it as a fruitless and delusional attempt to manage the worst excesses of capitalism. Achieving “a society of justice, equality and freedom from economic oppression,” the socialists and communists argued, would require more than “good Samaritanism.”[3] Many of the country’s early 20th century hard-leftists were drawn from the new immigrant community; the Social Gospel’s record of xenophobia (perhaps articulated best by Woodsworth in his 1909 book, Strangers Within Our Gates) further alienated Eastern Europeans and Scandinavians who were comfortable with the politics of communism.

For Social Gospel women, the track record of the old political parties as regards temperance and suffrage spoke for itself. Women who wanted to achieve social reform through electoral politics were more likely to find a home in the newer, smaller parties than they were among the Grits and Tories. Agnes Macphail (Progressive), Dorise Nielsen (CCF), and Gladys Strum (CCF) were three of the first five women elected to Ottawa. In 1944, Strum became the first woman to head up a provincial or federal political party when she took the presidency of the Saskatchewan CCF. At the provincial level, Louise McKinney (Nonpartisan League and United Farmers of Alberta) and Roberta MacAdams (nonpartisan) were both elected in 1917. Although women would also enjoy electoral success in the Liberal and Conservative parties, the progressive agendas of early feminists both contributed to, and would be better received, in the third parties.

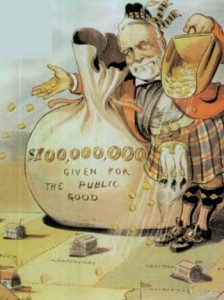

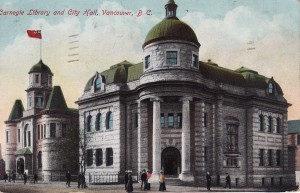

Measuring the intellectual consequence of a movement like the Social Gospel is difficult. It was so diffuse and appeared in so many guises that it inevitably overlapped with other engines of change. For example, the Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) was considered by his contemporary critics as the embodiment of the rapacious industrialist, whose enormous wealth was won at the expense of terrible working and living conditions for his employees; he wrote, however, on The Gospel of Wealth in 1889, calling for applied philanthropy on the part of his peers. In the last two decades of his life, he belonged to a Social Gospel church in New York and contributed millions of dollars to the improvement of civic and social infrastructure, a good deal of it in Canada. Philanthropy and charity were among the evangelical values promoted by the Social Gospel, and they remain important qualities in Canadian society, but they do not necessarily speak to the goal of social redemption. Nor, on the face of it, does social legislation like the Ontario Workmen’s Compensation Act of 1914, which was nonetheless the product of Social Gospel lobbying. What can be said with some confidence is that the influence of the social gospel outlasted its earliest spokeswomen and men, and can yet be seen in the fabric of social welfare laws and in the language of debates about urban conditions and inequality.

Key Points

- The Social Gospel movement grew out of changes in Protestant denominations and the rise of new churches in the 19th century.

- It was informed by deteriorating social and economic conditions in cities, and approached reform in urban areas and in remote and Aboriginal communities with missionary tactics.

- Elements within the Social Gospel movement were centred on Wesleyan College in Winnipeg, where a strongly social democratic wing developed.

- Social Gospellers targeted urban and social reform and some adopted new media and performance opportunities to produce a highly theatrical style outside of the traditional pulpit.

- The influence of the Social Gospel on Canadian politics and urban landscapes remains significant.

Attributions

Figure 7.6

YongeStreetMission by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.7

UofW by KrazyTea is under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

Figure 7.8

ASM-AngelusTemple Plaque 1923 02 by Foursquare Church Heritage Center is in the public domain.

Figure 7.9

Tommycropped by Samuell is in the public domain.

Figure 7.10

Carnegie-1903 by Louis Dalrymple is in the public domain.

Figure 7.11

Postcard: Carnegie Library and City Hall, c.1905 by Rob is in the public domain.

- Ramsay Cook, "Ambiguous Heritage: Wesley College and the Social Gospel Re-considered," Manitoba History, 19 (Spring 1990). ↵

- Eleanor J. Stebner, “More than Maternal Feminists and Good Samaritans: Women and the Social Gospel in Canada,” in Gender and the Social Gospel, eds. Wendy J. Deichmann Edwards and Carolyn De Swarte Gifford (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 57. ↵

- Eleanor J. Stebner “More than Maternal Feminists and Good Samaritans: Women and the Social Gospel in Canada,” Gender and the Social Gospel, eds. Wendy J. Deichmann Edwards and Carolyn De Swarte Gifford (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003): 62. ↵