9.14 Rural Canada in an Urban Century

Daniel Samson, Department of History, Brock University

At the time of Confederation, Canada was a rural country. By the middle of the 20th century, the majority of the country was urban. Today, it’s mostly urban. How did that happen? And what does that mean for our understanding of the country’s history? The most obvious answer is that the late 19th-century emergence of industrial capitalism meant that waged work was available in the towns and cities of the country, and that the country’s farms were able to feed this increasingly urban population.

Why were farmers able to feed so many more people? The most important change was the development of gas-powered engines and machinery. Farm mechanization had begun in Canada in the early 19th century, but increased dramatically in the years just before and after World War I. Productivity improved because mechanization meant that fewer people could do more labour on ever-larger farms. In the 1830s, most wheat was harvested by hand, greatly limiting the size of farms. Seventy years later, harvesting, winnowing, and threshing machines meant that 100s of acres, rather than 10s of acres, could be harvested and partially processed quickly and with far fewer human labourers. Many people, however, feared that all that productivity came at a cost. Rural depopulation also meant that rural communities shrank. Increased productivity, too, owed much to increased use of pesticides, adding to costs and multiplying the environmental consequences of agriculture. Mechanization, pesticide purchases, and other increasingly capital intensive techniques meant that steadily fewer families could sustain the higher costs of industrial agriculture.

Many of those who were moving to the city did so because farming had become untenable. Often, the owners of small farms sold out to larger producers. Indeed, farms continue to grow larger to this day. While the number of farms peaked in the 1930s, total farm acreage has actually increased over the course of the 20th century. The average size of a farm in Saskatchewan in 1914 was about 200 acres; by 1936, it had doubled to 400; and by 1956, had reached over 600 acres per farm. Today, that number is around 1,700 acres. By the early postwar period, farms could no longer really be considered “family farms”; they were businesses — larger in scale, capital intensive, and demanding stable access to markets.

Improvements in transportation also encouraged the growth of farms. Larger producers found ready markets for their products, and the increased availability of trains and steamships meant that Canadian farmers and ranchers, even those far from the ocean ports of Halifax and Montreal, could get their products to markets in Britain and the Caribbean. Rail integration in the 20th century opened access to the United States market. The Prairies were Canada’s breadbasket, producing more than four-fifths of the country’s wheat and exporting large quantities overseas, but none of that was even imaginable until the completion of the CPR and the integration of the West into national and international markets.

Scale had a major impact on not only farm size and market conditions, but also on productive and gender relationships in farm households. In the 19th century, most butter and cheese production was done by women in farm households. The rise of industrial butter and cheese production in the early 20th century pushed women out of dairying, and moved them from major productive household responsibilities to largely reproductive ones such as childrearing.

The state came to play a much greater role in the countryside. In the late 19th-century, federal experimental farms in small places like Nappan, Nova Scotia; and Kamloops, British Columbia; provincial agricultural colleges in places like Guelph, Ontario, and Truro, Nova Scotia; and statistical agencies across the country offered research, education, and support. During World War II, the federal government stepped in to regulate grain supplies and food production. State-run agencies like the National Wheat Board were created during the Great Depression to provide price stability, particularly for farmers dependent on international markets. Along with cooperatives and marketing boards for products like dairy and eggs, Canadian agriculture increasingly utilized market regulation to protect individual farmers against the uncertainties of international markets and price competition from the much larger United States agricultural sector.

The fisheries in eastern and western Canada faced similar challenges. Local inshore fisheries were increasingly at the mercy of industrial fishing operations with much larger ships, more productive gear, and direct relationships with national and international processors. In the great Depression, much like Prairie farmers, Maritime fishers turned to locally organized cooperatives and marketing agencies to allow them to compete against the industrial vessels. Factory trawlers and international markets dramatically increased the ability of the industry to harvest fish, resulting in near total depletion of major fish stocks like North Atlantic cod. By 1995, depletion was so great that the federal government had to shut down the cod fishery, effectively ending the economic viability of hundreds of small fishing communities in eastern Canada.

Canada also has a racialised dimension to its rural history. Indigenous people shaped their lives around participation in the fur trade, in small-scale agriculture, and local fisheries. Despite many political and social barriers, their successes were owing to their skills in working those distinctly rural economies. And from the 18th and 19th centuries onward, African-Nova Scotians were a predominantly rural population engaged in farming, fishing, and forestry in rural parts of the province. That explains the poet George Elliott Clarke’s reference to “Africadians” “gumboing” the salty recipes of Acadian cooking with the “fishy tastes of Coloured Refugees” — their culture, too, was shaped by life on the land and the sea.

Rural Canada today faces innumerable challenges. The sheer scale of production, declining population, increasing competition for prices and market share, and restrictive international trade agreements, and the difficulty of delivering basic social services — even schools — means that sustaining rural Canada is ever more difficult. Understanding the historic pattern helps us to better understand its complexities and its challenges.

Key Points

- The century of the city was made possible by the increased ability of farmers to feed urban populations (achieved through mechanization, chemicals, heavy capital investment, and consolidation of smaller farms into larger units able to achieve economies of scale).

- The role of the state in agriculture became increasingly important and took the form of research, marketing boards, and regulation of output.

- Rural fisheries communities were challenged by the increasing industrialization of ocean harvesting.

- In some rural areas the population became racialized: dominated by visible minorities including African Nova Scotians and Aboriginal communities.

Sources

The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/farming.html

Saskatchewan Department of Agriculture http://www.agriculture.gov.sk.ca/Default.aspx?DN=508d1598-3b66-428a-93ce-7ea9fa3abaee

Sarah Carter, “Two Acres and a Cow: ‘Peasant’ Farming and the Indians of the Northwest, 1889-1897,” Canadian Historical Review 70, 1 (March 1989): 27-52.

George Elliott Clarke, Whylah Falls (Vancouver, Polestar Press, 1990).

Daniel Samson, “’The Measure of Our Progress’: The Commission on Agriculture, Ontario, 1881”, in Nadine Vivier, ed., The Golden Age of State Enquiries: Rural enquiries in the nineteenth century (Turnhout BE, Brepols, 2014): 255-72.

Ken Sylvester, The Limits of Rural Capitalism: Family, Culture, and Markets in Montcalm, Manitoba, 1870-1940 (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2001).

John Thompson, The Harvests of War: The Prairie West, 1914-1918 (Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1978).

Miriam Wright, A Fishery for Modern Times: Industrialization of the Newfoundland Fishery, 1934-1968 (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2001).

Attributions

Figure 9.61

Observatory – Experimental Farm (Online MIKAN no.3318630) by William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010296 is in the public domain.

Figure 9.62

Steam plowing, Lethbridge, Alberta (HS85-10-23180) original by Canada. Patent and Copyright Office, Library and Archives Canada is in the public domain.

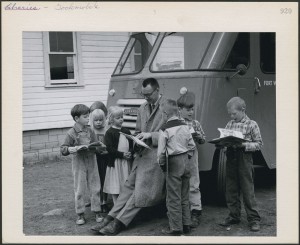

Figure 9.63

A group of children gather around a librarian and his Bookmobile in rural northwestern Ontario (Online MIKAN no.4369759) by Canada. Dept. of Manpower and Immigration / Library and Archives Canada is in the public domain.