12.3 Postmodern Politics

For all intents and purposes, the function of federal politics from 1867 to 1987 was to knit together the economic, political, social, and cultural concerns of the country and hold the federal structure together. When the Parti Québecois under Mssr. Lévesque was campaigning for sovereignty-association in 1980, every party in Ottawa came out in support of federalism (while offering varying degrees of reform for the relationship between Quebec and the ROC). The failure of the Meech Lake Accord shattered the illusion of a shared vision for federalism, even in the ROC.

Return to Charlottetown

Charlottetown, the Prince Edward Island capital, is where confederation was first proposed to the Atlantic colonies by the Canadians. That 1864 meeting enabled Charlottetown to bill itself as the “Cradle of Confederation,” despite the fact that PEI’s representatives decided to give the offer a pass on the first try. The symbolism of a return to where confederation began was clearly attractive to Conservative leader and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney; in 1992 he convened another meeting of Premiers on PEI with an eye to approving what some called “Meech 2.” Opponents of Meech Lake had pointed to the lack of consultation that preceded its creation, and Mulroney sought to address this failing with a new agreement. Extensive public discussion took place over nearly two years, including obtaining input and approval from the Assembly of First Nations, the Inuit Tapirisat, and the Métis National Council. The effect on the Charlottetown Accord was dramatic. Aboriginal rights were enshrined, as was Quebec’s distinct society clause. Senate reform was more clearly spelled out than in Meech, similar changes extended to the Supreme Court, and there was a commitment to education and social policies and principles. The overall trend was to empower the provinces and protect their ability to act independently on cultural matters. One facet of this shift was the proposal to eliminate the disallowance clause against which 19th century premiers like Oliver Mowat had railed.

All 10 premiers – including Quebec’s Liberal premier Robert Bourassa – approved of the Accord. The three major federal political parties – the governing Progressive Conservatives, the opposition Liberals, and the NDP – were also committed. In this instance, however, whatever was agreed to at the table would need to be approved in a national referendum.

Initially, broad public support seemed likely, even in Quebec (where it was, predictably, close). Several factors contributed to its defeat, the first of which was strong campaigns in Quebec by separatists (who were uncompromising in their view that a revived federal arrangement was not the same thing as autonomy) and the Prairie-based Reform Party (which argued that the Accord did not do enough to transform political structures, that it was a pact between old party elites, and that it gave too much to Quebec). The comprehensiveness of the Accord also invited criticisms: there was inevitably something with which anyone could quibble. Prime Minister Mulroney’s personal unpopularity was also a factor; a vote against Charlottetown was seen by some as a vote against an unpopular and (in some quarters) untrusted administration. A final and prominent component in the opposition camp was the involvement once again of Pierre Trudeau. A widely-read critique in MacLean’s magazine saw the former prime minister describe it as the end of federalism and a recipe for a disintegrated Canada. Indeed, supporters of the Accord similarly warned that a No vote could just as easily lead to the break-up of the country, which was a kind of brinksmanship that, on balance, probably favoured inertia over change, a No vote over a Yes.

On October 26, 1992, Canadians went to the polls to vote in a very rare national referendum. The results were complex, but the overall pattern was a victory for the No side with 54.4% of the vote. Four provinces voted against – British Columbians were the most adamant with 68% voting No – and the Territories split (Yukoners opposed it at 56%, but the NWT was 60.6% in favour). Without a strong tradition or experience of referenda, there was confusion as to how Ottawa would interpret the results, but there was a general consensus that rejection by any province could be a deal-breaker, particularly if that province was Quebec. In any event, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and the Prairie Provinces joined BC and the Yukon in rejecting the Accord. Charlottetown was as dead as Meech.

The referendum result was a a blow to the Progressive Conservatives’ credibility. Conversely, it enhanced the profile of the Reform Party and the Parti Québecois. Examining the results of the Accord referendum in Quebec, separatists began planning for a referendum of their own.

The 1995 Referendum

The 1993 federal election returned a Liberal majority government under Jean Chrétien. It was, as much as anything else, a rout of the Mulroney Conservatives (now under the leadership of Kim Campbell). The Tories didn’t win a single province, having been completely replaced by Reform in British Columbia and Alberta, and the Atlantic provinces provided the Conservatives with only one seat. The most ominous sign, however, was the appearance of the reappearance of an anti-confederation party at the federal level: the Bloc Québecois. Separatist strength in Quebec was growing once again.

The origins of the Bloc Québecois can be found in the long conflict between the federalist Liberals in Ottawa and the separatists in Quebec. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the role of Pierre Trudeau was pivotal in pushing the Liberals away from their old tolerance for Quebec nationalism. The separatist Parti Québecois offered a credible alternative at the provincial level (where, significantly, they defeated the provincial Liberals), but there was nothing equivalent at the federal level. (Theoretically – if not in practice – all Conservatives and Liberals from Quebec were federalists once they reached Ottawa.) In the 1980s, the anti-Liberal Péquistes increasingly looked to the Conservative Party to carry forward their agenda federally. Then, the lack of success of the Meech Lake Accord in 1990 drove the Conservative Minister of the Environment, Lucien Bouchard (b. 1938), to draft seven Quebec MPs — five Conservatives and two Liberals — into a new party.

Unlike the 1867-vintage Anti-Confederate Party from Nova Scotia, the Bloc proved highly successful at the polls. In its first outing in 1993, the BQ (or Béquistes or Bloquistes) won half the popular vote and more than two-thirds of the seats in Quebec.[1] This made the BQ the second-largest caucus in 1993-1997, despite being elected in only one province. A separatist party was now Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, and Mr. Bouchard was its leader.

Success at the federal level was echoed 11 months later in Quebec when the Liberal government of Bourassa was defeated by the Parti Québecois, which had been revived under the leadership of Jacques Parizeau (1930-2015). It is worth noting some of the numbers in this process: nearly 57% of Quebec voters voted No in the Charlottetown Accord referendum in 1992; the Bloc Québecois won 49.3% of the vote in Quebec in the 1993 federal election; and the Parti Québecois took just under 45% in the provincial election in 1994. Clearly, there was a bedrock of support for separatist and/or sovereigntist positions, perhaps enough to win a second referendum on sovereignty.

Despite the separatist strength going into this referendum campaign, divisions soon racked the leadership. Bouchard and Mario Dumont (b. 1970), the leader of the new conservative and populist Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) insisted that the referendum should include the option, and even the goal, of a continued economic and social partnership with Canada — this was the sovereigntist option. Parizeau and other hardliners argued for a clean break, a separatist or indépendantiste position. Fearing a fatal schism in the movement, Parizeau agreed to a referendum question that, if successful, would open sovereignty-association negotiations but, should those talks fail, the provincial government would be automatically empowered to declare independence unilaterally. The mechanisms for achieving autonomy were laid out in an Act Respecting the Future of Québec (also called the Sovereignty Bill or Bill 1), which passed first reading and waited on the Order Paper for the outcome of the referendum. As was the case in 1980, however, confusion over objectives led to a convoluted question:

Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Quebec and of the agreement signed on 12 June 1995?[2]

In the event of a successful referendum result, Bill 1 identified areas of partnership between Canada and the new country of Quebec, which included a customs union (essentially a free trade zone with a shared currency – the Canadian dollar); unfettered movement of individuals, services, capital, and goods; and a shared citizenship comparable to what could be found in the European Union. There was no clarity as to who would negotiate this agreement on the part of Canada. (Could Mssr. Bouchard participate? Would his caucus be permitted to vote on the outcome? What about Québecois civil servants in the federal administration?) Nevertheless, Parizeau’s concessions were enough to forge an alliance with Bouchard and Dumont. Bouchard took over the leadership of the Yes campaign in its last month, and the tide looked to be turning their way. One portent of the likely outcome came on the eve of the vote as Ottawa moved to get its CF-18 fighter aircraft out of Quebec even as the Parizeau government made plans to seize the Canadian Forces bases in the aftermath of a Yes victory.

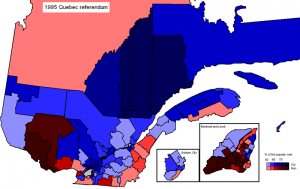

When the ballots were counted, the No side had once again triumphed but this time by the narrowest of majorities. More than 93% of the registered electorate turned out for the referendum, and 50.58% voted No. Leadership blunders and demographic factors had undermined the Yes side. Parizeau’s role could be singled out as polarizing because of his tendency to make ethno-nationalist comments that favoured the Canadien heritage far more than the pluralist society that Quebec had become. In the 15 years between the Lévesque referendum and the Parizeau-Bouchard-Dumont referendum, Quebec had become even more diverse and less pure laine (dominated by a population derived from the settlers of New France). The Francophone and Anglophone communities were growing slowly and, of course, many Anglophones had moved away between 1975 and 1995 in reaction to the Francization of daily life and commerce. A new and expanding community of immigrants with a higher fertility rate was making its presence felt, and their lack of connection to the historic grievances of New France, Lower Canada, and Quebec made the pitch for sovereignty that much more difficult. These newcomers – often lumped together as allophones – bore the brunt of Parizeau’s referendum night wrath. In a televised interview he claimed that the Yes side was defeated by “money … Anglo and ethnic votes.” The spectre of ethnic nationalism had been raised once again.

Border Disputes

Both the 1980 and the 1995 referendums provided opportunities for Canadians to think again about territorial assumptions. Quebec separatists viewed the entirety of the province’s boundaries as sacrosanct, but both the Inuit of Nunavik – the northern third of Quebec – and the Cree announced through their own referendums their intention to stay in Canada. The position they took was the same as Quebec’s: that they had a right to national self-determination. Given that the Cree homeland includes the enormous James Bay hydroelectric complex — symbolically and economically a mainstay of modern Quebec — the loss of that territory would be a body blow to the proposed independent state of Quebec.

The idea of partition had supporters within urban Quebec as well. Pierre Trudeau said in 1980 that “Si le Canada est divisible, le Québec doit être aussi divisible.” Anti-separatist anglophone communities in the Eastern Townships and the western half of the island of Montreal have also indicated a readiness to secede from Quebec so to maintain their connections with the rest of Canada.

What is more, Canada’s strategic interests have repeatedly been invoked in this discussion. Would it be necessary to create a Canadian corridor across southern Quebec to sustain connections with the Maritimes? Similarly, Quebec politicians have voiced a belief that the boundary with Labrador is not what it should be and that an independent Quebec would expect to receive some of that (iron ore rich) territory.

The effect of these challenges would be to pare Quebec back to something much more like Lower Canada or what the province was at the very beginning of Confederation. Naturally, this line of arguing is regarded in Quebec as highly provocative, and its opponents argue that it is unlikely to stand the test of international law.

There were several important outcomes to the referendum. As constitutional language around distinct society became more widely accepted in Canadian political culture, it was entrenched in legislation. The Calgary Declaration of 1997 parcelled out veto powers over future constitutional change and received the endorsement of every provincial government apart from Quebec. The next year, the Supreme Court declared on the question of unilateral declarations of independence: contrary to Mssr Parizeau’s plans, Quebec would not be able to simply walk out of confederation, although negotiations for an exit would be required of both sides. Finally, the slim victory of the No side pushed the Chrétien government to introduce the Clarity Act (2000) that demanded a clear question and a decisive outcome at the polls in any future referendum of national significance.

Eventually, constitution and referendum fatigue set in, and no government since 2000 has had an appetite for more debate on the subject. Quebec remains the only province that has not endorsed the Canada Act, and there is still no formally approved amending formula in place. The Canada Act is now more than 30 years old, which means it has outlasted both the Proclamation Act (1763) and the Act of Union (1840) and is currently the third longest-functioning constitution in the history of British North America, despite being fundamentally flawed.

The Campbell Moment

Something else happened in 1993 that marked a sea-change in Canadian political culture. The most visible was the appointment of a woman – Kim Campbell (b. 1947) – as Prime Minister. Campbell won the Progressive Conservative leadership convention and took over the reins from Brian Mulroney as he retired in June. Despite a promising start, Campbell’s popularity disintegrated once the election was called. Meech, the Free Trade Agreement, the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the Gulf War, and the entire record of the Mulroney administration was placed on Campbell’s shoulders. What’s more, the appearance of the Bloc in Quebec was mirrored by rising support in the West for the Reform Party under Preston Manning. Although the Reform Party had campaigned on the slogan “The West Wants In” from 1988, it was very much heir to a century of western alienation and was prepared to play separatist cards of its own. The ideological contrast between the BQ and Reform was significant in that the former pursued many of the social democratic and social justice issues that were the trademark of the Parti Québecois, whereas the latter was more archly conservative, in important ways, than the Mulroney and Campbell Tories. The effect of having two parties speaking up for regional disenchantment was decisive: the Progressive Conservatives suffered their most devastating loss on record as they were reduced to only two seats in the Commons. The NDP faired only slightly better, holding on to 9 of their pre-election 44 seats. Campbell was defeated in her own Vancouver-Centre riding and disappeared from politics.

An administration that lasts for only a couple of months might be said to have no legacy whatsoever. In the case of the Campbell administration, one could argue instead that its wholesale collapse was legacy aplenty. Was its rejection in 1993 a reaction to the neo-conservative, Thatcherite/Reaganomic posture taken by Mulroney or a rejection of his vision of a renewed constitutional process? In some respects, the outcome is reminiscent of the no-win situation faced by Laurier 90 years earlier when compromise only brought the contempt of Nationalist and Imperialist alike. In Campbell’s case, the Tory record on the constitution was not enough for Quebec and too much for the West. Campbell’s inability to reassure either side was certainly outstanding.[3] One should also point to the breakthrough of a woman leader, although Campbell shared this pioneering position with others. Jeanne Sauvé (1922-1993) became Canada’s first female Governor-General, serving from 1984 to 1990. Rita Leichert Johnston (b. 1935) was the first woman to lead a provincial government when, like Campbell, she took the poisoned chalice (in 1991) from a failing administration in British Columbia and lost in the very next election. In the same year, Nellie Cournoyea (b. 1940) became the first First Nations person to lead a government as Premier of the Northwest Territories (where a consensus-based selection process was used). Catharine Callbeck (b. 1939) was elected Premier of Prince Edward Island in 1993 in a more conventional parliamentary system and thus broke the curse of the appointed-successor. The fundamental breakthrough might properly belong to the federal NDP who elected Audrey McLaughlin as its caucus leader in 1989, which meant that two parties went into the 1993 campaign under female leaders. McLaughlin’s caucus survived but only barely, and she was succeeded in 1994 by Alexa McDonough. Sixty years after the Persons Case (1929), women were leading key parties and governments, and success in this regard would increase from province to province so that by 2012, half of the premiers were women.

Key Points

- Although the costs and benefits of federalism have been repeatedly questioned since 1867, the last 30 years has witnessed several attempts to rethink it, reconstruct it, and reject it.

- The failure of the Meech Lake Accord was followed by another, more consultative effort in the form of the Charlottetown Accord, which failed to win sufficient support in a national referendum.

- The rise of the Bloc Québécois as a federal separatist party was followed by another separatism referendum in Quebec. This was another No win, but only narrowly.

- The 1995 referendum and its fall-out included increased tensions between some ethno-nationalist Québécois and the growing allophone population.

- Aboriginal peoples in Quebec voted overwhelmingly against the referendum.

- Changes in the Progressive Conservative Party began in 1993 with the election of a female leader and the party’s subsequent electoral collapse.

Attributions

Figure 12.6

Canadian-Senate-chamber by Makaristos is in the public domain.

Figure 12.7

Constitutional Harness for the Wild Nag (Online MIKAN no.3964533) by Library and Archives Canada, R13244-171 is in the public domain.

Figure 12.8

Quebecref by Earl Andrew is in the public domain.

Figure 12.9

KimCampbell by Skcdoenut is used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license.

- This is the one breakaway party that has not, to date, been reunited with its ancestor party/parties. After 20 years, it remains a credible political entity. ↵

- Canada. Quebec. Quebec Sovereignty Referendum, 30 October 1995, in response to Bill 1 or the Sovereignty Bill. ↵

- Sharon Carstairs and Tim Higgins, Dancing Backwards: A Social History of Canadian Women in Politics (Winnipeg, MB: Heartland Associates, 2004), 282-285. ↵