11.6 Living with Treaties

Keith Smith, Departments of History and First Nations Studies, Vancouver Island University

Not unlike communities in Europe or elsewhere, the Indigenous peoples of North America confirmed access to resource sites, facilitated trade, resolved conflicts, settled alliances, and navigated the mass of other relations with their neighbours by negotiating agreements. When European newcomers found their way into Indigenous territories, they realized it was in their interest, and often necessary for their survival, to learn Indigenous treaty protocols and to fit themselves into Indigenous commercial networks. After these initial encounters, over time, treaty making changed in intent and content, but whether for military alliance, access to land and resources, or for some other reason, all of those involved understood that only agreements of this sort could protect the often divergent strategic, cultural, and economic interests of the treaty partners.[1]

The significance of treaty making to the newcomers is evident in Britain’s Royal Proclamation (1763) that, in part, committed it and then Canada to gain the consent of Indigenous Nations before settling in their territories. This commitment led to several treaties on Canada’s West Coast, and in what became Ontario and southern Manitoba prior to 1867. Soon after Confederation, the treaty process continued with the negotiation of the so-called “numbered treaties,” the first seven of which were concluded between 1871 and 1877 and covered the southern region between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains. For its part, Canada was primarily concerned with the acquisition of land and the fulfillment of its promise to British Columbia for a transcontinental railway. First Nations, on the other hand, were generally interested in protecting their territories and resources from incursion, while at the same time ensuring their cultural survival and independence. For them, these treaties were peace treaties. As Piikani (Peigan) elder Cecile Many Guns (aka: Grassy Water) confirmed almost a century after the treaties, the intent was that there would be “no more fighting between anyone, everybody will be friends…. Everybody will be in peace.”[2]

From the perspective of the newcomers, the transfer of land stood above all other policy considerations, and the numbered treaties were presented as successful mechanisms by both politicians of the day and many later historians. However, it is becoming increasingly recognized that rather than representing everything that was agreed to, the written treaties are much more reflective of Canada’s goals and Euro-Canadian interpretations of treaty-making, and much less representative of the objectives of First Nations and of Indigenous understandings of treaty processes. Many of the arrangements that were presented and agreed to orally during treaty negotiations are absent or minimized in the text of the numbered treaties.[3] The actual meaning of these treaties remains in dispute among historians and in the courts.

Reserves

As a central provision of the numbered treaties, and where there were no treaties as Federal Government policy initiatives, isolated enclaves called Indian reserves were created to accommodate Indigenous people. The reserve system, as it developed in the mid to late 19th century, was meant as a temporary measure only, providing closed sites where missionaries and agents of the state could indoctrinate Indigenous populations in the economic, political, religious, and social conduct acceptable to settler Canada. Reserves offered residents refuge of sort from the various forms of discrimination they faced in the outside world, but to policy makers and church officials, they were laboratories of reform where residents could be observed and judged and where “Indian-ness” could be instructed, legislated, or coerced out of Indigenous people.[4] On these fragments of ancestral territories, Indigenous residents held the right to occupancy only. Ownership and title remained in the hands of Canada.

Since non-Indigenous lawmakers took for themselves, even in treaty areas, absolute authority to decide who would own land, reserve size depended largely on local settler demand. Even in areas covered by the numbered treaties, reserve size was calculated differentially on the basis of between 160 and 640 acres per family of five, while in British Columbia, for example, 10 acres per family was established as the standard. These inequities, and the smaller average reserve land base in Canada compared to the United States, were recognized and challenged by Indigenous political movements such as the Allied Tribes of British Columbia during the First World War and Interwar period, but they have largely remained to the present day.[5]

Regardless of the original size of reserves, even these small tracts remaining to Indigenous people were often under threat. While the Federal Government restricted the ability of reserve communities to manage the lands they lived on, Canadian officials were more than willing to alienate reserve lands themselves to meet settler demands for mineral, forest, or agricultural lands; for the construction of transportation routes or military sites; or for a myriad of other purposes. While often, though not always, Indigenous agreement of a sort was sought, this consent was regularly acquired under circumstances that were at best questionable. Additionally, the sale of reserve lands was consistently presented as being in the long-term interests of the reserve communities, although it was railway and corporate executives and other members of the settler elite — including senior Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) and other public officials — who gained possession of the alienated reserve lands during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[6] Some of these land sales continue to be the subject of land claims and court challenges.

The contradictions here are apparent. While Canada presented its policies as beneficial to Indigenous peoples, and while it maintained that its goal was to remake reserve residents into farmers, the best agricultural land was the first to be removed from First Nations’ control. Even the right to use modern farming equipment and to participate in training programs, farm organizations, and wheat pools like their non-Native neighbours were curbed by Canadian officials. Further, amendments were made to the Indian Act soon after its creation, and more strictly applied after the mid-1880s, whereby reserve residents were required to secure a permit before selling or giving away any goods located or produced on reserves or by reserve residents. While some, like Cree elder John Tootoosis (1899-1989), recognized the positive aspects of the permit system as a means to protect First Nations vendors and consumers, he nonetheless saw it as a “loaded gun” that was, in the end, turned against those it was ostensibly designed to protect. Certainly, there was ongoing resistance to all of this from Indigenous communities, but for the most part, the protests were disregarded in Ottawa.[7]

Restricting Movement and Cultural Practices

Most Canadians are secure in their right to move about freely and practice whatever form of spirituality they choose, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Canadian and church authorities went to some lengths to restrict both for those they defined as Indians. The kinds of activities allowed on ever-shrinking reserves were increasingly limited, restrictions were placed on movement, and cultural practices among reserve residents were policed and penalized. The suppression of liberty among Indigenous peoples was central to Canada’s Indian policy.

The Pass System

The confinement of Indigenous peoples to reserves was set in motion through the application of a matrix of laws, regulations, and policies meant to “elevate” reserve residents while advancing the interests of non-Indigenous settlers. In much of Canada, movement was limited through the vagrancy provisions of the Criminal Code or the restrictions against trespass in the Indian Act. However, in the region that became the prairie provinces, the most notorious and comprehensive element of the restrictive matrix was implemented through a Federal Government policy known as the pass system. Under this initiative, a reserve resident was required to first secure a written pass from their Indian agent if they wanted to visit family or friends in a nearby village; check on their children at a residential school; participate in a celebration or attend a cultural event in a neighbouring community; leave their reserve to hunt, fish, and collect resources; find paid employment; travel to urban centres; or leave the reserve for any other reason.[8] According to Assiniboine Chief Dan Kennedy of the Carry the Kettle First Nation in Saskatchewan, “[t]he Indian reserve was a veritable concentration camp.”[9]

Official correspondence from the decade before 1885 reveals that procedures were already in place and that there was a will at all levels of the D.I.A., the North-West Mounted Police, and political hierarchies, including Prime Minister John A. Macdonald himself, to restrict Indigenous movement in the West. The Northwest Resistance of 1885 provided the justification for the application of a comprehensive pass system in the Prairie West, regardless of whether individuals or their communities were part of the resistance.

All of those involved in the implementation of the pass system understood that it had no basis in Canadian law. It was never included in the Indian Act or any other piece of Canadian legislation, which naturally put senior police officials in a difficult position. The regulations were at odds with settlers who relied on Indigenous labour and trade (and so opposed the restrictions), but high-ranking policemen also feared that they would be humiliated once Indigenous people recognized the pass system lacked a legal foundation and then chose not to comply with the policy. Generally, the NWMP/RNWMP/RCMP leadership preferred compliance by persuasion rather than by force, although individual officers were at times even more zealous than Indian agents, and chose to apply force when they felt it was necessary. Indigenous people naturally resisted their confinement to reserves and seem to have made little distinction between being persuaded to remain on, or return to, their reserves and being escorted back by a contingent of mounted policemen. They tended to choose to comply with the policy, or openly defy it, according their own judgment of the specific situation.

There is textual evidence that passes continued to be issued until after World War I, and oral evidence that the pass system remained in operation into the mid-1930s at least. Even though Canada never had the capacity to forcibly restrict all off-reserve movement, the will of both the police and the D.I.A. to do what they could in this regard — regardless of the lack of legal foundation — is evident, even if some in the upper echelons of the police were sometimes uncomfortable.

Cultural Restriction

Not only were Indigenous people restricted in their right to move about freely, even in their traditional territories, but also spiritual practices that were fundamental to personal and community identity and well-being — and that had been practiced since time immemorial — were targeted for suppression. State and church officials alike were intolerant of these practices, which they regarded as alien and immoral. Canadian and religious authorities also recognized that spiritual systems were integral components of the cultural, political, economic, and social structures of Indigenous communities. To transform one, the others had to be reconfigured as well.[10]

While there is evidence of this cultural repression across the country, the ceremonies of West Coast peoples known collectively as the potlatch received particular attention from politicians, missionaries, and government officials. The term potlatch refers to a complex of strictly regulated ceremonies that continue to be of critical significance to the Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish, Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Heiltsuk, and other peoples of the North West Coast of North America. The potlatch is the central institution that binds each of these societies together. Potlatches can be held to confirm leadership, alliances, or access to land and resources. Names (and, thus, status) can be given or passed down, debts repaid, dishonour erased, marriages performed, births announced, or the loss of loved ones memorialized. Potlatches provide a forum for history to be transmitted and verified, and gifts are given to witnesses who are obliged to remember and confirm what they have experienced. In addition to handling and healing earthly concerns, potlatches also have important spiritual components.[11]

Many in late 19th and early 20th century settler society who were fortunate enough to witness potlatch ceremonies first hand, or who benefited materially by providing supplies, supported their continuation. On the other hand, Indian agents who saw families working for months to meet the expense of a potlatch denounced the institution as “foolish, wasteful, and demoralizing.” It seemed to them that these ceremonies were held solely to give away material goods, a concept that was directly opposite to settler goals of capitalist accumulation and private property, and which simultaneously challenged settler understandings of what constituted “wealth.”[12] Missionaries, for their part, tended to see potlatches simply as a manifestation of evil. Thomas Crosby (1840-1914), who worked as a Methodist lay missionary to Coast Salish peoples of southern Vancouver Island and the lower Fraser Valley, from 1863 to the 1890s, said of potlatches, “Of the many evils of heathenism, with the exception of witchcraft, the potlatch is the worst, and one of the most difficult to root out.”[13]

In 1884, the Indian Act was amended to include a ban on the potlatch along with the expressly spiritual dances associated with plains ceremonial practices. Unlike the pass system, the prohibition against these institutions and practices was backed up by the force of law that became ever more strict and comprehensive over time. Despite the legislative prohibitions, many communities felt they had no alternative but to continue to hold potlatches and dances, even if they went to considerable effort to make them more portable and keep them out of the view of missionaries and Indian agents. Even with these precautions, there was a wave of prosecutions and subsequent incarcerations soon after World War I. It wasn’t until 1951 that the prohibitions against Indigenous ceremonies were finally dropped from the Indian Act. Some of the masks and other spiritual objects confiscated during the period of the ban have since been returned to their owners, but many others remain in the hands of museums and private collectors.

Key Points

- Treaties evolved as instruments for negotiating accommodation between Aboriginal peoples and the newcomer society. By the late 19th century, the newcomers saw treaties as a means to acquire resources and manage Aboriginal populations.

- The final versions of the numbered treaties do not always or honestly reflect what was agreed (or understood to have taken place) in the treaty-making processes.

- Reserves were accepted by Aboriginal peoples as lands that were protected against intrusion; the Canadians carved out reserves as contained spaces in which assimilative efforts could be conducted more efficiently.

- Reserve size and resources were determined more by settler needs than Aboriginal requirements or expectations.

- Federal policies like the pass system and prohibitions against the potlatch and the sun dance were bureaucratic tools used to extinguish Aboriginal culture while restricting basic freedoms of movement and belief.

Attributions

Figure 11.7

Indian Chiefs 1873 Medal, Presented to commemorate Treaty Number 3 (Queen Victoria) (Online MIKAN no.2851194) by Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1970-27-8M is in the public domain.

Figure 11.8

Totem pole with modern tombstone (Online MIKAN no.3349323) by Library and Archives Canada is in the public domain.

Figure 11.9

In P49 – Indian Potlach Alert Bay B.C. by City of Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: In P49 is in the public domain.

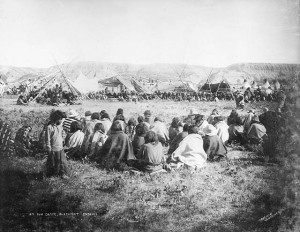

Figure 11.10

Sun Dance, Blackfeet Indians (Online MIKAN no.3368318) by Trueman / Library and Archives Canada / C-014106 is in the public domain.

- On treaty making in Canada across time see J. R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009). ↵

- Interview with Mrs. Cecile Many Guns conducted by Dila Provost and Albert Yellowhorn Sr., n.d. University of Regina, oURspace, http://ourspace.uregina.ca/handle/10294/586. ↵

- Sarah Carter, Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900 (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 118-127. ↵

- Keith Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance, and Resistance: Indigenous Communities in Western Canada, 1877-1927 (Edmonton, AB: University of Athabasca Press, 2009), 50. ↵

- Ibid., 132; Robert White-Harvey, “Reservation Geography and Restoration of Native Self-Government,” The Dalhousie Law Journal 17, no. 2 (1994): 588-589; Statement of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia for the Government of British Columbia (Vancouver: Cowan & Brookhouse, 1919) in LAC, RG 10, vol. 3821, file 59335, part 4A. ↵

- Robert Cail, Land, Man and the Law: The Disposal of Crown Lands in British Columbia, 1871-1913 (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1974), 14; Peggy Martin-McGuire, First Nation Land Surrenders on the Prairies, 1896-1911 (Ottawa, ON: Indian Claims Commission, 1998), 15-16, 42, 493-494, and 497-498. ↵

- Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 253-258 and 156-158; Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance and Resistance, 99-103; Jean Goodwill and Norma Sluman, John Tootoosis (Winnipeg, MB: Pemmican Publications, 1984), 123-125. ↵

- This section on the pass system is drawn from Smith, Liberalism, Surveillance and Resistance, 60-77. ↵

- Dan Kennedy, Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief, ed. James R. Stevens (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1972), 87. ↵

- Katherine Pettipas, Severing the Ties that Bind: Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies (Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 1994), 3-4. ↵

- John Lutz, Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2008), 58. ↵

- Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890, 2nd ed. (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1992), 206-207; Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 160. ↵

- Thomas Crosby, Among the An-Ko-me-nums or Flathead Tribes of Indians of the Pacific Coast (Toronto, ON: William Briggs, 1907), 106. ↵