6.17 Japanese Canadians in the Second World War

Jordan Stanger-Ross (University of Victoria) Pamela Sugiman (Ryerson University) & the Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective

The Second World War internment of all “persons of the Japanese race” serves as a powerful reminder to all Canadians that the rights of citizenship can be legally revoked and that the history of our country is not one of racial harmony.

In September 1946, a Japanese Canadian woman named Tsurukichi Takemoto wrote officials to protest what she had experienced since Canada’s entry into the war in the Pacific (7 December 1941). Alongside many others in her community, Tsurukichi had been interned in Greenwood, a former “ghost town” in the interior of British Columbia and one of several similarly isolated sites used by the federal government.

For roughly 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent, regardless of social class, sex, age, and generation, it turned out that race superseded citizenship. Angered by the violation of her rights, in two letters dated 5 September 1946, Tsurukichi forcefully reminded government officials, “[w]e are not Japanese Nationals.” With outrage, she explained:

I did not answer until now because your letter just made me mad enough not to answer . . . Isn’t the method you’re using like the Nazis? Do you think it is democratic? No! I certainly think you’re just like the Fascists confiscating people’s property, chasing them out of their homes, sending them out to a kind of a concentration camp, special registration cards, permits for traveling [sic]. Don’t you think this is the method used in dictatorship countries[?] Democracy means no racial discrimination, or is it the very opposite[?][1]

What historical conditions precipitated Tsurukichi’s anger? Did her charges hit their mark? What prompted some Japanese Canadians to liken their treatment at the hands of the Canadian government to those enacted by the most brutally racist regimes of the era? These questions remain troubling today.

The Government’s wartime treatment of Japanese Canadians was supported by hundreds of legal enactments, most of them made possible by the War Measures Act. The War Measures Act gave the cabinet of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King the power to regulate all persons “of the Japanese race” through Orders-in-Council: that is, declarations of law that bypassed debate in the legislature and proved resistant to judicial challenge.

Such policies had dramatic consequences for all Japanese Canadians. Property owned by Japanese Canadians was stolen, looted, destroyed, and neglected. What survived was sold without the consent of its owners. While they received some compensation for these sales, owners had no opportunity to challenge the (often highly unfavourable) terms of exchange and they lost the right not to sell. Further, the proceeds of these sales were doled out as allowances to Japanese Canadians who were struggling to support themselves while interned. Tsurukichi’s letter highlights one woman’s resistance to the forced sale of her family’s property. Informed that government agents had sold her family’s belongings for a fraction of their value, Tsurukichi became “mad enough not to answer.” Family heirlooms, including fine Japanese pottery, she informed officials, “are not what you think they are”: such belongings left in trust to Canadian officials had monetary value and emotional meaning that was all but discarded as they were auctioned to eager buyers while their legitimate owners remained interned. Another Japanese Canadian, whose home, 17.5 acres of land, and his personal belongings had been sold without his consent, wrote, “It does not seem just that as Canadians my family should be deprived of a home which to us meant more than just a home. It was, to us, the foundation of security and freedom as Canadian citizens.”[2]

Internment meant different things for different groups of people. In addition to the wartime dispossession of property, government policies required that Japanese Canadians carry special registration cards and obey curfews, face restricted mobility and communications, and live with the constant threat of arbitrary searches of their homes. As well, the internment resulted in the separation of families, forced labour for men, and for some, incarceration in prisoner of war camps in northern Ontario. When the government declared Canada’s west coast a “protected area,” the entire Japanese Canadian population was uprooted. Some 12,000 Japanese Canadians were sent by train to live in hastily constructed shacks and abandoned buildings in various parts of the BC interior: Greenwood, Sandon, Kaslo, New Denver, Rosebery, Slocan City, Bay Farm, Popoff, Lemon Creek, and Tashme. Approximately 4,000 were sent to labour on sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. And slightly over 1,000 who had sufficient funds established so-called self-supporting camps where they essentially paid for the costs of their own internment.

Toward the war’s end, Japanese Canadians were forced to “choose” between a further uprooting to the unknown territory of Eastern Canada and exile to Japan, a country that many had never before visited. Almost 4,000 Japanese Canadians were eventually deported to Japan. All Japanese Canadians were prohibited from returning to British Columbia until 1949.

In the decades following these events, defenders of the policies have argued that they resulted from the pressures of war. In the first year of Canada’s war with Japan, many politicians and social commentators expressed genuine, though ill-informed, concerns that Japanese Canadians could threaten the security of Canada’s West Coast. However, the enforcement of policies that violated the rights and freedoms of all “persons of the Japanese race,” rather than more targeted measures to regulate the lives of individuals specifically suspected of collusion with Japan, reflected the racist ideologies that buttressed the wartime treatment of the Japanese Canadian community. Prime Minister King expressed such ideologies in 1942 when he privately stated that “no matter how honourable they might appear to be, or how long they may have been away from Japan, naturalized, or even those who were born in [Canada]. Everyone of them . . . would be saboteurs and would help Japan when the moment came.”[3] Cabinet Minister Ian Mackenzie, the federal politician most closely connected with these policies similarly argued to a constituent:

I do not think that any question of nationality [that is, Canadian citizenship] should prevent our having the right to advocate . . . their complete removal to their own country. Their country should never have been Canada . . . I do not believe the Japanese are an assimilable race.[4]

Such positions, as critics such as Tsurukichi Takemoto realized, were not merely the regrettable isolated actions of some Canadians who panicked at a time of war. Rather, they were part of the systemic racism that pervades Canada’s history.[5]

Key Points

- Following Pearl Harbor, some 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent or nationality were stripped of their property and interned under the War Measures Act.

- Internees’ property was often auctioned off or otherwise sold with no compensation to the owners.

- Japanese Canadians’ rights were severely curtailed and, at war’s end, they were encouraged to either migrate to Eastern Canada or choose exile to Japan.

- White Canadians’ fears of the Japanese community were entangled in a racist notion that essentialized loyalty to the Japanese Empire.

Attributions

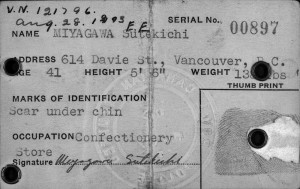

Figure 6.31

Back of Sutekichi Miyagawa’s internment identification card issued by the Canadian Government in compliance with Order-in-Council P.C. 117 (Online MIKAN no. 3226949) by Library and Archives Canada/PA-103543 is in the public domain.

Figure 6.32

Fishermen’s Reserve rounding up Japanese-Canadian fishing vessels (Online MIKAN no.3193627) by Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-037467 is in the public domain.

Figure 6.33

David Suzuki and his two sisters in an internment camp (Online MIKAN no. 3526055) by Margaret C. Foster, Library and Archives Canada, Acc. no. 1976-087, PA-187835 is in the public domain.

- Mrs. Tsurukichi Takemoto to H.F. Green [Image 1634], and to G.B. Spain [1635], 5 September 1946, Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property Records, Vancouver Office Files, Reel C9476, Héritage Project, Canadiana.org. ↵

- Mr. Rikizo Yoneyama to Minister of Justice [Image 1448], 31 July 1944, Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property Records, Vancouver Office Files, Reel C9476, Héritage Project, Canadiana.org. ↵

- The Diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King, February 28, 1942, available online at Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter to Godwin, 7 December 1942, File 70-25, MG 27 III-B5, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- For information on the Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective and its publishing conventions, see www.landscapesofinjustice.com. ↵