6.18 From V-E to V-J

Victory in Europe, Victory in Japan

As winter settled in across western and southern Europe, the Canadian units in Italy had an opportunity to join up with those in France and the Low Countries. The crisis of insufficient troop reinforcements that necessitated calling up additional troops passed. Fighting resumed in March 1945 and did not let up until the collapse of Germany on 6 May. Victory in Europe (V-E) was celebrated across Canada and with drunken rioting in Halifax. What Canadians at home did not see and could barely be expected to imagine was the relief of slave labour camps across the Reich, and especially the liberation of concentration camps.

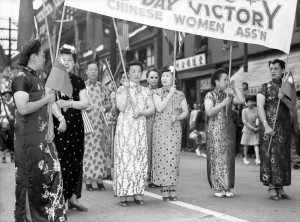

The war as a whole, however, was still not over. Russian troops had met with Allied forces at the Elbe River, a symbol of the military success of the Alliance in Europe. There was, however, no immediate likelihood of a Japanese surrender. Stalin agreed to Roosevelt’s request to turn the Red Army to the east to liberate China. Although Japan was struggling to maintain its shipping lanes and the flow of fuel to its navies, the Empire’s ground troops put up enormous resistance on every island the Americans besieged. The back of Japanese resolve was finally broken when the Red Army took Manchuria and the Americans dropped atomic bombs on two major cities: Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Canadians participated in the development of the atomic bomb and in the supply of uranium but otherwise they played no significant or direct role in the Asia-Pacific War. This did not stop them from celebrating V-J Day (Victory over Japan Day), especially in Vancouver.

Taking the Toll

The number of troops lost in the war overall represented another blow to the Canadian population, and it came only a generation after the mortality of the First World War. Some 45,000 Canadians were killed in battle or at sea and thousands more were maimed. As was the case at the end of the First War, the extent of psychological trauma was unmeasured, although the stigma of “shell shock” had been replaced in the Canadian forces by a greater respect for “battle exhaustion.”[1] (The term “post-traumatic stress disorder” would not appear until the 1970s.) The fall of Japan was followed by the liberation of POW camps containing Canadian prisoners. Their captivity began in December 1941 with the capture of Hong Kong and their numbers were increased with other Canadians captured at Singapore. Their treatment was appalling, mortality rates were very high, and psychological damage was severe. Reintegration of service men and women into Canada in peacetime would present challenges.

Against this toll, Canada’s cities were not in ruins. Infrastructure was in some respects badly neglected and factory machinery was worn out or in sore need of reorientation to peacetime production; in some respects, rebuilding from scratch would have been easier than repurposing exhausted equipment and assembly lines. The ability and will of the state to intervene in the economic and social well-being of Canadians was far advanced on what it had been in the 1930s. Some of these social and economic themes are explored in the chapters that follow. What is worth underlining here is that the wars were unprecedented events globally and for Canada in particular. Canada had long been a country that looked upriver from the Gulf of St. Lawrence; on account of two world wars, Canada was now a nation that had a growing sense of having a place in the wider world.

The Kamloops Kid

Kanao Inouye was born in Kamloops, BC to Japanese immigrants. He attended the local elementary school and then the family moved to the coast where he attended Vancouver Technical School. In 1938 he travelled to Japan to complete his education, and in 1942 he was an enlisted man serving as an interpreter in the Imperial Army and on hand for the mopping up after the fall of Hong Kong.

Inouye’s principal role was that of interpreter but he was given a long leash when it came to abusing and even torturing prisoners and suspected spies. He lashed out at Canadian POWs in particular, claiming that he was getting even for years of ill-treatment by whites in BC. Known to the Canadian prisoners as the “Kamloops Kid,” Inouye’s brutality led to deaths and, subsequently, to his arrest after Japan’s capitulation.

While several Japanese officers stood trial at war’s end for war crimes, Sargeant Inouye could not. Born in Canada, he was viewed by the international tribunal as a “Canadian citizen.” This was technically impossible as Canadian citizenship – as opposed to British subjecthood – was only introduced in 1946. What’s more, as a Japanese Canadian his citizenship rights in Canada were poor before 1941 and they became even more limited with the Internment. So, immediately after the war, it seemed that he was going to be spared execution because of a citizenship that he could never have claimed at home in Canada.

The irony deepens. As a “Canadian citizen” Inouye was subject to Canadian laws, specifically those regarding treason. In 1947 he was retried, found guilty, and hanged.

Key Points

- The fall of Germany in 1945 was followed by the collapse of Japan after two atomic bombs were dropped on populated centres.

- The death toll among Canadian troops and other service men and women was not as great as in the First World War, but it surpassed 45,000.

- One effect of the war was to shift Canada toward a more global orientation, economically and politically.

Attributions

Figure 6.34

Infantrymen of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade liberating Zwolle, Netherlands, 14 April 1945 (Online MIKAN no. 3191782) by Lieut. Donald I. Grant / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-145972 is in the public domain.

Figure 6.35

Bergen-Belsen by John Douglas Belshaw is used under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

Figure 6.36

CVA 586-3970 – V.J. Day Chinese Dragon Parade by City of Vancouver Archives/Photo by Donn B.A. Williams, 14 August 1945 is in the public domain.

- Terry Copp and William McAndrew, Battle Exhaustion: Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the Canadian Army, 1939-1945 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990). ↵