8.14 Economic Nationalism

Doug Owram, Department of History, University of British Columbia - Okanagan

Relatively speaking, Canada came out of the Second World War in good shape. It was able, over the next few years, to absorb the wartime debt, convert its economy to peacetime production, and set the stage for nearly three decades of prosperity.

However, there was a problem. Throughout much of its history, Canada sought to maintain political and economic autonomy by balancing the overwhelming influences of its two most influential trading partners and cultural influences, Great Britain and the United States. The so-called North Atlantic triangle prevented Canada from being pulled exclusively into the orbit of either of the much larger powers around it.

By the post-war years, that equilibrium was failing. Britain, already weakened by the First World War, left the Second World War mired in debt and challenged by an obsolete manufacturing base. In contrast, the United States was indisputably the world’s greatest economic and military power — the first “superpower.” By the 1950s, two-thirds of Canada’s exports and imports were with the United States. Even more dramatically, more than three quarters of all foreign capital invested in Canada came from south of the border. When such economic dominance was compounded by the influence of Hollywood, American magazines, radio, and the emerging medium of television, many worried — as did Canada’s foremost economist, Harold Innis — that we had gone “from colony to nation to colony.” Thus, economic policy in these years was inseparable from wider fears about Canadian identity.

| Table 8.1 Foreign Long Term Capital invested in Canada (%) | ||

| Decade | UK | USA |

|---|---|---|

| 1926 | 44% | 53% |

| 1945 | 25% | 70% |

| 1055 | 18% | 70% |

| Data source: Canada. “Domestic Saving and Foreign Investment in Canada.” Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects, Final Report (Ottawa, ON: Queen’s Printer, 1958). Table 18.2, 381. | ||

Over the next 20 years, Canadians wrestled with how to manage a relationship with an ally, economic powerhouse, and dominant neighbour. For all political parties, Canadian nationalism and American influence became a significant and often contentious issue.

Traditionally, it was the Conservative party that had stood as the primary defender of the British connection and opponent of excessive American influence. The pattern seemed to continue when, in 1957, John Diefenbaker defeated the long-reigning Liberal party, to some extent, on the question of undue American influence in the building of a trans-Canada oil pipeline. However, old traditions were hard to maintain in the new world of the American superpower.

For the six years they were in power, the Conservatives tried various strategies. The first approach was both the most traditional and the most unrealistic. The Conservatives sought, in various ways, to strengthen British trade as a means to counter-balance American influence. Diefenbaker talked of diverting 15% of trade to Britain, but he had no idea how to carry it through. Britain’s economic clout was no longer anything near that of the United States. Second, the power that Britain retained was increasingly oriented to the European continent — a direction that would eventually lead Britain into the European economic zone. By 1963, the year the Conservatives left office, British trade with Canada was lower in percentage than it had been in 1957.

The second approach to counteracting American influence was to try to develop internal measures that would decrease the American presence. Drawing on John A Macdonald’s vision for the west, Diefenbaker called for Canadians to invest in the North. Through programs such as “Roads to Resources,” the government sought to create the necessary infrastructure. Moreover, as the North was a territory not a province, the federal government had a freer hand. In 1960 oil and gas regulations sought to limit outside influence. In the end, though, the northern economic strategy remained more vision than substance, and investment patterns were not altered. American multi-nationals still dominated key Canadian sectors like energy. Overall, during these years, American foreign investment in Canada increased by around 30%, whereas British investment in Canada remained stagnant.

When the Liberals returned to power in 1963, they did so in part because of Canadians unease with Diefenbaker’s policies toward America — though more related to defense than trade. The message conveyed during the election campaign by the new Prime Minister Lester Pearson (1897-1972), was to work for better relations with the United States. Everything, therefore, seemed to point to less economic nationalism. Certainly, there were tendencies in that direction, most importantly the 1965 Automotive Products Agreement (known as the Auto Pact) that created a formidable North American market for Canadian-made autos and auto parts. The message seemed clear: co-operation created jobs, even if the companies were American controlled.

Nationalism had not disappeared, however. On the right, Diefenbaker remained leader of the opposition, condemning the Liberals for abandoning British ties and selling out to American interests. On the left, the old CCF party had transformed into the more urban and nationalistic New Democratic Party (NDP). American Cold War policy, especially in Vietnam, made the NDP suspicious of the United States’ influence over any part of Canadian life. In the increasingly restive mood of the 1960s, therefore, the Liberals were aware they had to watch pressures from nationalism on the left and right.

Not all the pressure was external to the Liberal party. Walter Gordon, Pearson’s Finance Minister, had chaired the 1955-1957 Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects that raised questions about foreign ownership. In his first budget, he moved on his concerns by instituting various measures, including a 30% takeover tax on foreigners buying control of a Canadian company. The reaction from business was immediate and harsh, and Gordon had to retreat. Nonetheless, as Finance Minister until 1965, Gordon continued to propose nationalist measures. Even after leaving the cabinet, he was able to use his influence to help establish a new study of foreign investment, led by economist (and NDP co-founder) Mel Watkins.

The findings of Watkin’s Task Force on Foreign Ownership and the Structure of Canadian Investment were even more alarmist than Gordon’s study a decade earlier. The NDP embraced the Watkins Report (1968) and faced an internal battle as elements within the party, known as the Waffle movement, took an even more radical position in the following year by condemning American imperialism in all its forms. The extreme political rhetoric of the later 1960s and early 1970s kept the issue before the public, while maintaining pressure on the governing Liberals to take at least some action.

In response to both internal and external pressure, the Liberals under Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau took two concrete steps. The first was the Canada Development Corporation (CDC), designed in 1971 to help increase Canadian investment in Canadian companies. The second arrived in 1973 in the form of the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA), which gave government the power to review and possibly prevent a foreign takeover of a Canadian company.

Although FIRA and the CDC remained on the books until the mid-1980s, the fact is that the high level of concern about foreign investment was already waning. An economic recession in 1973 suddenly made new money more attractive, whatever the source. The NDP expelled the Waffle movement in 1972 and, exhausted by its internal battles, turned increasingly toward a more domestic and less divisive focus. As for the Conservatives, John Diefenbaker had been forced out in 1967, and the party’s stance was morphing into a more pro-American one. This shift would culminate in a major free trade agreement with the United States in 1988, crafted by Tory Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

Of course Canadian concern about American dominance will always be a part of our national landscape. However, growing markets in Europe and Asia and growing pools of investment capital at home mean that — viewed from the perspective of the present — the period from the 1950s through to the early 1970s stand out as a particularly volatile era in Canadian economic nationalism.

Key Points

- Canada’s post-WWII economic recovery depended largely on transferring export dependence on Britain to the United States.

- It also involved accepting and encouraging American dominance in foreign capital investment.

- Strategies to counter American influence in the Canadian economy included Roads to Resources, tariff arrangements like the Auto Pact, and the establishment of FIRA.

- Ottawa’s efforts to secure greater economic sovereignty have largely failed, and the issue has proved divisive even with individual political parties.

Attributions

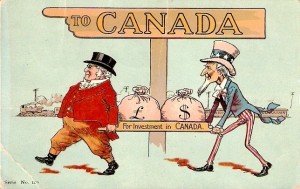

Figure 8.22

Postcard (postmarked 1907) depicting John Bull and Uncle Sam under sign “To Canada” bringing in sacks of money “for investment in Canada” is in the public domain.