9.15 Cold War Themes

A signifier of cultural change in the Cold War years was the transformation of musical styles and tastes. Radio and film contributed significantly to this process, as did the commercial recording industry. Music was increasingly commodified and so, too, were musicians. Trends in English Canada — which were strongly influenced by what was going on in the United States and Britain — were very different from what occurred in French Canada (elements of which are considered in Section 10.14). It would be wrong to say that this era saw the universal triumph of rock music because, in Quebec as in much of the rest of the non-anglophone world, other traditions were more important and more resilient.

The Beat Goes On

The dominant threads in popular music in the early 1950s were strongly connected with the big band sound, close harmony vocal groups (often made up of siblings), and the more accessible forms of jazz. American and British musicians were increasingly challenging these standards, with electric blues, rockabilly, and skiffle — all forms that would contribute in some measure to what became known in the early 1950s as rock and roll (aka: rock’n’roll). A transition phase saw the rise of closely managed studio productions, which are now more associated with pop music. The gospel-inflected “The Mocking Bird” by Toronto’s The Four Lads is generally thought to be the breakthrough moment in Canadian pop/rock. It is markedly distinct from, but closely related to, WWII-era swing and close harmony bands. This style did not entirely go away. Throughout this period and into the 1970s, artists like Juliette Cavazzi (b. 1927) remained popular, a fact that was made possible by CBC radio programming that favoured more conservative sounds. The influence of the national broadcaster in this respects goes some distance to explain the slow take-off of a younger sound.

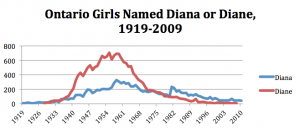

It wasn’t until 1957 that Canada produced its first genuine pop star, in Ottawa’s Paul Anka (b. 1941). His debut hit song, “Diana,” is held to be responsible for the sudden surge in the popularity of this girls’ name in Canada (as can be seen in the Ontario data in Figure 9.65[1]). Anka’s desperate plea — he was a hormonally charged 16-year old when “Diana” was recorded — pulls the song out of the mainstream and into something much closer to the crooner-rock of the 1950s.

American influences on popular music in Canada in the 1950s and early 1960s were extensive. The infrastructure of commercial radio and television favoured American recording artists and placed Canadians at a huge disadvantage. Ronnie Hawkins (b. 1935) moved to Canada from the United States and was highly influential from 1958 to 1964, establishing The Hawks, a Canadian backing band. It featured Garth Hudson (b. 1937), Richard Manuel (1943-1986), Robbie Robertson (b. 1943), Rick Danko (1943-1999), and the American drummer Levon Helm (1940-2012), who together would eventually re-launch themselves as The Band.

By the mid-1960s, however, the playing field had been somewhat leveled by the impact of the British Invasion. Bands like the Beatles, the Animals, the Dave Clark Five, and the Rolling Stones combined elements of American rock — including the music and style of both Buddy Holly (1936-1959) and Elvis Presley (1935-1977) — with British soul, Merseybeat, and skiffle to produce a more aggressively dynamic sound. Even British pop and soul singers like Petula Clark (b. 1932) and Dusty Springfield (1939-1999) were critical influences at this point. American musicians — even acts like the Beach Boys, which were credited as an influence on the Beatles — struggled to reclaim prominence in their own market, as did Canadians.

Swinging Sixties

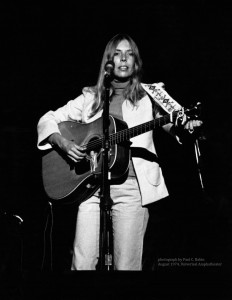

In Canada, the major commercial breakthroughs came from the folk-blues-rock community. Oscar Brand (b. 1920) emerged as a leading performer and a godfather of the movement in 1963, as did Ian Tyson (b. 1933). Buffy Sainte Marie (b. 1941) began her very long and extremely varied career with a folk hit in 1964, the same year that Joni Mitchell (b. 1943) began singing in Toronto. Gordon Lightfoot (b. 1938) was writing songs for Tyson and his partner Sylvia Fricker Tyson (b. 1940) in 1963 to 1964 and launched his own folk touring act in 1967. Leonard Cohen (b. 1934) released Songs of Leonard Cohen in 1967, and a year later Anne Murray (b. 1945) recorded “Snowbird.” All of these musicians benefited from a growing appetite in the United States for folk singer-songwriters, typified by Bob Dylan (b. 1941); Joan Baez (b. 1941); Pete Seegar (1919-2014); The Weavers; Judy Collins (b. 1939); and Peter, Paul, and Mary — almost all of whom at some point performed music written by their Canadian contemporaries. Looking at the birth-dates of these figures reminds us that the folk revival of the 1960s was led by people born before or at the very start of the baby boom and who were just that much closer to a rural version of Canada than their younger peers in the rock movement.

Of that 1960s rock’n’roll generation, no one stands out more than Neil Young (b. 1945). The son of the prominent sports journalist, Scott Young, Neil Young moved to California in the late 1960s, where he became part of a folk-rock supergroup, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. In many ways, Young exemplifies the essence of a difficult-to-define musical style in that his physically exhausting live performances, high degree of musicianship on guitar, and emphasis on authenticity — rather than studio work, thrashing chords, and studied affect — are what most stands out. Joni Mitchell, a contemporary and peer both in Canada and the United States, is comparable in that she demands more of her chief instrument — her voice — than was typical of even 1950s harmony singers or the earlier gospel-folk singers.

CanCon

Young and Mitchell were not the only Canadian musicians to seek fame and fortune south of the border. By 1968, it was clear that Canadian talent was profoundly underappreciated at home. Without record sales and radio play in the United States, a Canadian pop or rock performer could not expect to receive much attention from commercial radio north of the border. Beginning in 1968, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) began a project to stimulate artistic output under Canadian content (CanCon) rules. From 1971, radio stations were required to devote one-quarter of their airtime to Canadian music. To do so, many stations had to actively search out producers and performers who could deliver records that met the criteria. The focus was to be placed on Canadian songs performed by Canadian musicians.

Sometimes the criteria were stretched in bizarre ways: the British psychedelic/progressive rock band, Procol Harum, in 1971 recorded their song “Conquistador” with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra (ESO) providing support. The ESO’s involvement conferred on a clearly British product CanCon advantages: “Conquistador” went to #7 in the Canadian charts. Other strategies for avoiding the CanCon constraints were pursued, as well. Some radio stations addressed what they saw as revenue-draining local recordings by playing them continuously in the small hours of the night, in what became known disparagingly as “beaver hours.”

The new CanCon rules took time to create benefits and some of the musicians who were supported at the beginning were clearly filler rather than great local talent. The program nonetheless produced a generation of performers who could expect and would receive more playtime on Canadian commercial radio than their predecessors. Bands like the Guess Who appeared in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and enjoyed enormous popularity in Canada and abroad, as did their spin-off project, Bachman-Turner Overdrive. Rush emerged out of blues tradition and moved into Progressive (Prog) Rock in the late 1970s. One could provide a long list of bands that enjoyed every degree of popularity from one-hit-wonderdom to long term success: Trooper, Prism, FM, April Wine, and Chilliwack are among the most prominent of the 1970s and early 1980s bands. It is probably no coincidence that this was the decade that saw the greatest number of baby boomers entering adulthood, a fact that no doubt explains the endurance even now of both classic rock stations and what has become anthemic hockey-arena music. Which is to say, it doesn’t get played because it’s necessarily good; it gets played because of the demographic that nurtured it along and still proclaims its popularity.

“All this machinery making modern music”

The conundrum facing Canadian musicians in general, and rock musicians in particular, was the business model of the industry. Record labels stateside dominated the business through their control of distribution and their influence on radio networks. The sale of records was key to making a living as a musician. So, despite rock’n’roll’s do-it-yourself, or DIY attitude — embodied in every four-piece band that wrote and performed their own music — it was necessary to make use of the recording industry. American labels like Capitol established branch plants north of the border where they used the same business model, one of the features of which was exclusive ownership of a musician’s product. A rock musician whose work was defined by live performances could now only get meaningful engagements through recording agents and industry impresarios. Bands played live in support of their studio product and, increasingly, merchandise like posters and t-shirts. As rock giants emerged, they could demand arena and then stadium venues, absorbing more and more of the disposable wealth of a younger generation of consumers, and leaving less and less behind for bands that could not get, or did not want to get, signed to an exploitative recording contract. Musicians who once appeared edgy or challenging were smoothed into manicured products.

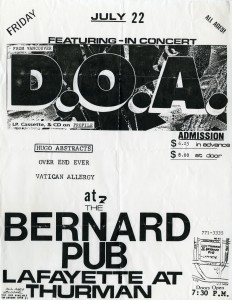

One reaction to this was the rise of alternative and independent recording artists and performers. Punk Rock was, in its late 1970s incarnation, an expression of alienation from the pop music industry’s emphasis on extravagance in the studio and on the stage. Bands like DOA, Teenage Head, Viletones, Pointed Sticks, and the Subhumans recorded very little but performed a lot, breathing second life into old downtown venues too small for rock gods. Appreciated as much for their political, anti-authority stance as for their music, the Canadian punk movement (and, to a lesser extent, New Wave) found audiences in the United States and Britain. World music influences began to shape Canadian performers as well, as could be seen in Toronto especially. Jamaican and other West Indian immigrants in the 1960s brought ska, rock steady, and reggae to Canada where it evolved its own sound. Fresh immigration from a destabilizing Caribbean brought new artists but, by the 1980s, the Canadian variant was distinctive for its less confrontational forms. Largely contained to the multicultural cities, this was and remains, nevertheless, a vibrant field.

While innovators in these areas were trying to recapture the spontaneity and DIY feel of earlier musical generations, the studio business model had its acolytes in Canada. Big rock’n’roll machines — Bryan Adams, Prism, Streetheart, Tom Cochrane, Headpins, Gowan, and Platinum Blond — dominated the airwaves and the arenas in the 1980s. These were bands that mostly echoed older rock’n’roll themes from the 1950s which included endlessly cruising in cars, heterosexual adolescent love, and nostalgia. Nothing captures this better than Adams’ anachronistic hit “Summer of ’69”: born in 1959, Adams was probably not “young and restless” at the age of 10, nor is it likely he bought a guitar at the “five and dime.” Few of these musicians had much to say about global politics, although Prism’s “Armageddon” conjures the possibility of a nuclear holocaust through which everyone just rocks it out.

French-Canadian music evolved very differently in the Cold War years. Its roots were a combination of Québecois and Acadien fiddle/folk music along with the chansons of France, whose recordings were eagerly imported and consumed. Aglaé (aka: Jocelyne Deslongchamps, 1933-1984) and Guylaine Guy (b. 1929) were two Québecois chanteuses who became very popular in mid-1950s Paris, reversing the flow of talent for a while. Michel Louvain (b. 1937) was Quebec’s foremost singer in the “crooner” tradition in the late 1950s. Other continental influences in this period include the pop-rock form, yé-yé (somewhat akin to what is today called “twee pop”) taken up by Nanette Workman (b. 1945) and the slightly more rocking styles of musicians like Louise Forestier (b. 1943) in the late 1960s. Prog Rock became more popular, and earlier in French Canada than in English Canada, and jazz remained more at home in Montreal than anywhere else in the country. Although one could point to two solitudes in terms of popular and commercial music in these years, the influence of folk music remains a common (if differently coloured) thread. For every Randy Bachman in these years, there seems to be, in English Canada at least, one Bruce Cockburn; likewise, in Quebec, even pop-rockers like Forestier felt comfortable reviving music with roots in the 19th if not the 18th century.

This is by no means a full survey of musical styles and innovations in the late 20th century, but it draws attention to some important elements. Music matters in this period in part because it emerged as the dominant art form. However grand the galleries or the symphony halls might have become in the 1960s and 1970s, nothing was quite as likely as a daily encounter with pop music. AM stations multiplied, and FM took tentative steps in 1968 to move away from easy listening and classical into album rock programming. More and more television airtime had a pop music component. It became a means to express social change, even as it manifested change itself. Nowhere was this more evident than in the transformation of youth culture in the 1960s.

Key Points

- The postwar period would see the emergence of new musical styles that nevertheless drew on older and even traditional forms.

- Canadian pop music struggled for years in a commercial context that favoured both American and British recording artists, large studios and distributors, and impresarios who featured big acts while neglecting local talent.

- The early strength in Canadian pop music came from the folk-blues-rock performers like Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, and Neil Young.

- Government efforts to support Canadian culture extended to Cancon rules that were intended to benefit homegrown musicians. In the short term, it reinforced a star system that favoured a few big acts, but by the 1980s, there was a number of reasonably successful acts.

- Alternative music — broadly defined — emerged as a reaction to and a kind of sub-culture of the popular music industry, drawing on punk and immigrant cultures.

- Popular music traditions in Quebec were, in almost every regard, distinctive in these years.

Attributions

Figure 9.64

Four Lads Greatest Hits by Peter Zimmerman is used under a CC-BY-2.0 license.

Figure 9.65

Diana by John Douglas Belshaw is used under a CC-BY-4.0 license.

Figure 9.66

Joni mitchell 1974 by Paul C Babin is in the public domain.

Figure 9.67

D.O.A. by kopper is used under a CC-BY-2.0 license.

- Ontario. Top names (female), accessed 13 January 2015 from https://www.ontario.ca/data/ontario-top-baby-names-female. ↵