9.12 The 1980s

The oil crises of the 1970s continued to damage the western economy, driving up government deficits in one country after the next (see Section 8.10). Economic stagnation combined with inflation — a rare occurrence — to produce what was called “stagflation.” The dominant economic theory of the time in Canada, a kind of modified Keynesianism, offered limited help in dealing with this new phenomenon. Trudeau’s 1975 to 1979 administration responded with wage and price controls and limited the ability of trade unions to bargain for improved incomes as a means of controlling inflation. This strategy undermined the postwar settlement and brought the Liberals into conflict with labour, thereby enhancing the NDP’s position.

At the same time, the most — and increasingly —popular economic theory on the right called for achieving growth through monetary policy. Monetarism (described in Section 8.16) was invoked as a way of adjusting incomes outside of wage settlements. Coupled to a belief in the efficacy of free markets and the necessity of reducing the role of the state, these approaches together constituted the neo-liberal (sometimes referred to as neo-conservative) agenda. Canadians were not in a hurry to embrace these policies, but the outside world — specifically, the United States and the United Kingdom — did so from the late 1970s on. Canada was inevitably caught up in this tide.

Trudeau’s Return

It is worth noting that Trudeau’s unpopularity in 1979 — particularly in the West— did not recover during the Clark administration. Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes returned a Liberal majority in 1980, in a campaign in which Trudeau was regarded by his own minders as a liability to be kept mostly out of sight. Apart from two seats in Manitoba, the West did not elect a single Liberal. If this reflected, in part, the Liberal approach to energy politics the situation only worsened with the subsequent introduction of the National Energy Policy (see Section 8.10). These developments were bound up in what became known as western alienation, a parallel to Quebec’s dissatisfaction with Confederation and longstanding Maritime disenchantment.

What sustained Trudeau’s standing nationally was his constitutional achievement in 1982. Efforts began in 1980 to recreate the consensus between provincial leaders that was briefly achieved at Victoria (in 1971) but these ended in bitter disagreement between the premiers and Trudeau’s designate in this process, Jean Chrétien (b. 1934). A November 1981 meeting between Chrétien and a group of Premiers in the kitchen of the Government Conference Centre produced what was called the Kitchen Accord (and its makers, inevitably, were the Kitchen Cabinet). Lévesque arrived the following morning and rejected the Accord as a betrayal of trust on the part of his colleagues, after which it was known in Quebec as the “Night of the Long Knives.”[1]

The federal government then settled on a unilateral approach to the problem, one that the provinces challenged unsuccessfully in the Supreme Court. This left the path open for Ottawa to request of Westminster that the constitution be patriated to Canada. Faced with this seeming fait accompli, nine of the provinces agreed to an arrangement in which the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms would protect some of their interests through a notwithstanding clause in the forthcoming Canada Act (1982). An amending formula, however, was not settled on.

Quebec remained a hold-out in these talks and has not relinquished that position since. At the time, Trudeau (probably correctly) believed that Lévesque would not consent to any proposal to reform a constitution from which he would prefer an outright break. Certainly, if Liberal premier Bourassa in 1971 felt pressure from nationalistes to reject the Victoria Charter, the separatist premier Lévesque would feel that pressure even more.

Despite the constitutional victory — as it was seen by many — Trudeau’s personal popularity continued to sag. By 1984, he had spent 15 years in the job and helmed the country through some of its most troubled years. Generation gaps, campus unrest, FLQ bombs, the sexual revolution, second-wave feminism, two OPEC oil crises, the end of the postwar boom, the arrival in adulthood of all of the baby boomers, and two major constitutional battles — including a nail-biting referendum in Quebec — represent only a sample of the seismic forces that were metamorphosing the country and exhausting the prime minister.

In the background, Trudeau’s private life had gone from glamour to prurient gossip and judgment. It is important to note in this regard the different values that were manifest in 1970s and 1980s Canada: as Christopher Dummitt shows in Section 9.5, a leader with a secret life as complicated and messy as that of Mackenzie King could be in the spotlight for 20 years without fear of public or press prying. By contrast, Trudeau’s playboy lifestyle in the 1960s drew comment and criticism; his relationship with, marriage to, and divorce from Margaret Sinclair (b. 1949) — a woman 30 years his junior and described by the press as a “flower child” — was scrutinized at every turn. Sinclair came from the Liberal establishment in British Columbia (her father was a cabinet minister under Louis St. Laurent), but she was 22 at the time of her marriage and subjected to the first wave of political paparazzi — whether at home, on official business, or visiting her favourite discotheque. Sinclair’s departure from 24 Sussex Drive (which she has described bitterly as “the Crown jewel of the federal penitentiary system”[2]) was a blow to Trudeau’s own well-being. His role as the nation’s most famous single parent was yet another way in which he was a pioneer among prime ministers.

Trudeau’s legacy is a complex one. His administrations were buffeted by demands for change, and they made many missteps along the way. There were important advances and substantial retreats as well. Material change — the Charter, the Constitution — was probably less consequential in some respects than the emotions he evoked in people. Early in Trudeau’s prime ministership, the famously acerbic poet Irving Layton said, “In Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Canada has at last produced a leader worthy of assassination.” Trudeau’s undoubted intellectual powers, his coolly rational, Jesuitical way of arguing a point, his disregard for decorum (as when he slid down a bannister at the Chateau Laurier or did a pirouette behind the Queen), and his cut-throat debating style in the Commons aroused feelings of admiration and accusations of unbridled arrogance. As much as many of his predecessors have been disliked or their policies despised, Trudeau was simultaneously the most celebrated and hated man to hold the office. His successors would be held to a changed standard and all would prove to be “no Trudeau.”

Mulroney, Meech, and More

As neo-liberalism took hold in Britain and America, so too it acquired acolytes in Canada. The fading popularity of the Liberals worked to the advantage of the Conservatives. Clark’s failure to hold onto power put his leadership in peril and, with it, the ability of the Red Tories to influence the party in a decade of rising social conservative values. In 1983, the Progressive Conservative Party’s leadership convention ousted Clark and elected Brian Mulroney (b. 1939) as leader.

Born in Baie-Comeau, educated in Quebec, New Brunswick, and, Nova Scotia, Mulroney was conspicuously fluent in English and French and as much at home in boardroom Montreal as he was in rural Maritimes and Quebec. A political animal from an early age, he worked in Ottawa under the Diefenbaker government before shifting to corporate law. In the 1970s, he played an important and prominent role in the Cliche Commission enquiry into labour issues at the James Bay hydroelectric project. His disclosure of Mafia involvement in union actions put him in the public eye for the first time. The Commission also found Mulroney working alongside Lucien Bouchard (b. 1938) and in close contact with Bourassa, two political allies who would play important roles in the 1980s and 1990s. Understood to be an opportunist who could play the Blue and Red sides of the PC Party, Mulroney decided in 1984 to move his campaign in a direction that was consonant with highly popular neo-conservative regimes in Washington and London.

The 1984 campaign combined a swing to the right with a rejection of the Liberals — now led by the very uncertain John Turner (b. 1929). Turner, like Trudeau, had an earlier reputation as a good-looking, mid-century playboy (he had famously dated Princess Margaret in the 1950s) and as an effective Minister of Justice and then Minister of Finance under Trudeau. But he broke with Trudeau in 1975 over the issue of wage and price controls and spent the next nine years working on Bay Street as a corporate lawyer. He won a seat in the 1980 election but was not the robust fighter he had been years before. He made an easy target for Mulroney and, in one of the earliest televised debates between federal party leaders, Turner withered and crumbled under accusations that he lacked the nerve to reverse egregious patronage appointments made by Trudeau on his way out of office.

The Liberal record in tatters, Mulroney did more than inherit office from a failing government. He built huge momentum across the country. Although Diefenbaker had made headway into Quebec, it was Mulroney who reestablished the party of Borden in that province, winning 58 of 75 seats. This massive majority in the Commons, however, did not translate into an easy legislative ride. The Senate was dominated by years of Liberal appointments with little likelihood of change on the horizon. For the first time in decades, the upper house was inclined to scrutinize legislation and send it back to the Commons for amendment. These practices frustrated Progressive Conservatives who were hungry for change, and stimulated calls for senate reform. Mulroney faced other challenges, however, and some of these were internal. Having been out of office for a generation (notwithstanding the Clark regime of nine months), there was a backlog of demands from patronage appointment hopefuls. As well, the country was running a significant deficit, and attempts to reduce it only imperiled Mulroney’s ability to fund projects that would reward the party faithful.

The prime minister responded with closer relations with the United States and constitutional reforms.

New Reciprocity

Free trade had always been an issue associated with the Liberal Party; now Mulroney seized upon it from a neo-liberal angle. The Auto Pact already provided for severely lowered tariffs in that sector and there were other sectoral trade discussions underway since the 1960s. Reducing trade barriers further and more generally was seen in the 1980s as a means to boost activity in a slow moving Canadian economy. It also suited Mulroney’s pro-American attitudes, which were put on display at a St. Patrick’s Day meeting in Quebec City in 1984 with President Ronald Reagan. The “Shamrock Summit” between the two Irish-North American leaders laid the groundwork for a freer marketplace, a sign that Ottawa was absorbing the neo-liberal view that government regulation of trade was stifling growth. The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) that followed was resisted bitterly by some manufacturers and many spokespersons for the cultural sector. The acclaimed author, Margaret Atwood (b. 1939), was only the most prominent of the many writers and artists who challenged the proposed agreement on the grounds that it would result in the destruction of Canadian culture. In a presentation to a parliamentary committee on free trade, she said, “Canada as a separate but dominated country has done about as well under the US as women, worldwide, have done under men; about the only position they’ve ever adopted towards us, country to country, has been the missionary position, and we were not on top.”[3] The final agreement provided protection to Canadian education systems, the health sector, and cultural industries; it did not, however, cover off American access to Canadian water (for the economic impacts of the FTA, see Section 8.16).

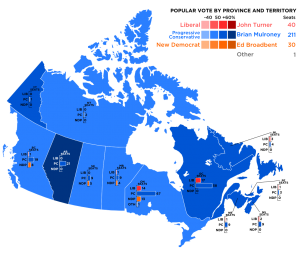

The final draft left many Canadians uneasy and concerned about national sovereignty in an integrated North American economy. The NDP’s opposition was predictable, given its record of concerns about American commercial and cultural imperialism; the Liberal Party also threw its weight against the proposed treaty, thereby claiming the anti-reciprocity position that was, for a century, a trademark of John A. Macdonald’s Conservative Party. Faced with obstruction in the Liberal-dominated Senate, Mulroney opted to take the issue to the polls. The 1988 election that followed became a single-issue campaign, a poll on whether to accept the FTA. Although Tory dominance survived only in Alberta and Quebec, the NDP and Liberals split the vote everywhere else and were unable to avoid a second Mulroney majority. The FTA was proclaimed and in effect on 1 January 1989.

The Meech Lake Accord

The possibility of constitutional change was able to take advantage of the momentum created by the Canada Act. The most critical piece was the issue of an amending formula. Mulroney’s popularity in Quebec was largely built on his commitment to meaningful change in this area, so long as it would address Quebecers’ concerns. Lévesque indicated a willingness to seek a resolution, a move that undermined his support in the PQ, led to his resignation as leader, and the Party’s defeat at the hands of Bourassa’s revived Liberal Party in December 1985. In April 1987, Mulroney invited the provincial premiers to a retreat at Meech Lake, where a nine-hour meeting produced agreement on an amending formula, a distinct society clause for Quebec, a system for filling senate openings and Supreme Court positions with individuals recommended by the provinces, and greater provincial influence over immigration issues. This was the only thing that was accomplished with alacrity in the brief life of the Meech Lake Accord. In June 1990, the Accord was dead, unable to make it through the various shoals of Canadian politics. What had gone wrong?

The signs at first were promising. The opposition leaders— John Turner for the Liberals and Ed Broadbent (b. 1936) for the NDP — endorsed the Accord and the public seemed predisposed to support an agreement that would put an end to the long-running constitutional saga. As Bourassa was inclined to point out, all of Quebec’s requirements had been offered up by Ottawa at one point or another over the previous 20 years, so there was little new to be concerned about. Only four of the premiers at Meech were not Conservatives, and one of those was BC Social Credit premier Bill Bennett (1932-2015) (an ideological conservative); another was Bourassa, a Liberal, who was adamantly supportive of the Accord. That left Howard Pawley (1934-2015) (NDP), who was replaced within weeks by the Conservative government of Gary Filmon (b. 1942). All of this bode well.

And then, a month after the Meech Lake meeting, Pierre Trudeau resurfaced. No longer an MP, his thoughts on the subject were nevertheless newsworthy. He called Mulroney a “weakling” for caving into Quebec’s interests, drew attention to the dilution of federal powers to the detriment of the whole nation, took aim at the distinct society clause, and made salient points about the threat the Accord might pose to the Charter rights of less-privileged Canadians. Federalists within the national and Quebec arm of the Liberal Party began deserting Turner’s supportive position.

This was not enough to completely derail the process. A signing ceremony in June 1987 in Ottawa turned into an all-nighter of negotiations on fine points but agreement was reached and the document inked. Now, as per the existing amendment process, the clock was running: Meech Lake required official Parliamentary and provincial approval within three years or it would die on the order paper.

Three years is a long time in politics. First, Hatfield’s Conservative government in New Brunswick was devastated at the polls by the Frank McKenna (b. 1948) -led Liberal Party which, remarkably, won every seat in the legislature. Then the Pawley government fell and a minority government took its place. In 1989, Newfoundland voters threw out the Conservative Tom Rideout (b. 1948) government and voted in the Liberals under Clyde Wells (b. 1937), who — along with McKenna— believed that the Accord talks should be reopened.

Public opinion, too, was beginning to abandon the Accord. A turning point in this regard was the response of the Quebec Liberals to a Supreme Court decision on the province’s sign laws. The Court found the extensive ban on English-language signage violated Charter rights. Rather than concede the point, Bourassa drew up new legislation, Bill 178, which used the notwithstanding clause to renew the commitment to French-only signs. One of the aspects of the Meech Lake Accord was that the clause was not to be used to get around Charter rights. English-Canadian politicians in Quebec and elsewhere were appalled; both New Brunswick and Manitoba now turned against the Accord.

In the absence of public hearings before Meech Lake, what followed was a public outpouring of criticism. There was some support, to be sure, but accusations of elitism and the creation — through the distinct society clause —of what was called asymmetrical federalism raised concerns from coast to coast. New Brunswick’s opposition prompted Mulroney to appoint Jean Charest (b. 1964), a young cabinet member from Quebec, to head up a Commission to find a way forward on some of these issues. The Charest Commission recommended that the distinct society clause be subject to the Charter, a change that appealed to English Canadian premiers but which did not play well in Quebec. Bourassa would have nothing to do with the amendments and Charest’s suggestions prompted Mulroney’s old friend and cabinet minister, Lucien Bouchard (b. 1938), to resign from the government (some accounts claim he was fired). Always an undisguised nationaliste, Bouchard now declared himself committed to the sovereigntist vision of independence. Just as Turner was dealing with division in the ranks of the Liberal Party, now Mulroney was facing down senior members in his own cabinet.

Mulroney was himself an important factor in the failure of Meech Lake. His management style worked well in executive boardrooms, but it lacked any consultative features. There were no public hearings, admittedly a rarity in the 1980s. The optics were bad as well: a roomful of white male politicians who were all — with the exception of PEI’s Joe Ghiz (1945-1996), who was of Lebanese descent — drawn from northwestern European stock, ought to have noticed that they lacked credibility to speak for women, Aboriginal people, new immigrant Canadians, and several other constituencies. No sooner was the Accord announced, some of these groups began to mobilize opposition to the process as much as to its product. Mulroney has been criticized as being too much in a rush to get an agreement and, thus, too ready to make concessions of federal authority where there were strong arguments against doing so. In the aftermath of a final round of revisions and amendments in June 1990, Mulroney claimed in an interview that his last strategy was to gather the premiers and force an agreement. It was in this interview that he used the phrase “roll the dice” to describe the process. If the premiers had not felt manipulated or treated with contempt before, several certainly did at this point. The public, too, was outraged by Mulroney’s gaff. It was this reaction that prompted Manitoba premier Filmon to call for public hearings. What support Mulroney had enjoyed from Liberal leadership hopeful Jean Chrétien now evaporated.

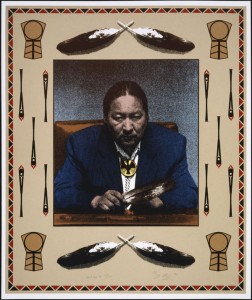

The final scene of the Meech Lake Accord drama was held in the Manitoba legislature. The process involved in reaching the Accord consensus angered Aboriginal political figures, and they were dissatisfied as well with the actual contents of the agreement. Aboriginal people were never consulted, and their role or place in Canadian society was submerged beneath the rhetoric of two founding nations. Approval of the Accord by Manitoba required two votes in the legislature, the first being a vote permitting the second vote. It was during this debate that a northern Manitoba NDP member of the legislative assembly, Elijah Harper (1949-2013), holding a single eagle feather, used legitimate procedural delays to obstruct the assembly. This act, conducted by a First Nations man — the first Treaty Indian in provincial politics — was an important moment in drawing Canadians’ attention to Aboriginal issues and the question of where they fit within the equation of constitutional discussions. Harper’s refusal in the face of substantial pressure to accede was noted widely and regarded as courageous and, in the end, it was successful. The vote could not be taken, the deadline passed, and Meech died.

Key Points

- Changing economic circumstances produced a change in the political culture, manifest in a turn toward neo-liberal (aka: neo-conservative) positions.

- Trudeau’s success in patriating the constitution produced the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canada Act. What was missing was an amending formula.

- Despite these accomplishments, Trudeau’s popularity continued to fall, and it did so in an era of increasingly personalized politics.

- Brian Mulroney’s prime ministership moved the Conservatives from a Red Tory to a Blue Tory position on social policies.

- Mulroney broke, too, with generations of Tory leaders by endorsing closer relations with the United States in politics and in trade, manifest in the signing of the Free Trade Agreement.

- The Conservative government also moved in 1987 to settle the issue of the amending formula. The Meech Lake Accord was agreed between all ten provinces and Ottawa, but its support dissipated in the three years that followed.

- Canadian political culture generally became more ideologically charged in the 1980s, more personal, and simultaneously more public, with growing demands for consultative and transparent processes.

- The role of Elijah Harper in the defeat of the Meech Lake Accord is regarded as a watershed moment after which Aboriginal peoples’ involvement was more consistently sought.

Attributions

Figure 9.50

Terry Fox by Simon Fraser University – University Communications is used under a CC-BY-2.0 license.

Figure 9.51

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II with Prime Minister The Rt. Hon. Pierre Elliott Trudeau signing the Constitution. (Online MIKAN no.3205977) by Robert Cooper / Library and Archives Canada / PA-141503 has nil restrictions on use.

Figure 9.52

Canada 1984 Federal Election by Lokal_Profil is used under CC-BY-SA-2.5 license.

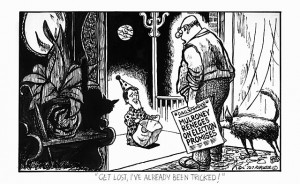

Figure 9.53

“Get lost, I’ve already been tricked!” (Online MIKAN no.2866224) by Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1987-42-435 has nil restrictions on use.

Figure 9.54

Just Say No [Elijah Harper] (Online MIKAN no.2910105) by Library and Archives Canada, David Neel collection, 1991-344, C-138082 has nil restrictions on use. Copyright assigned to Library and Archives Canada by copyright owner Roy Carless.

- This term alludes to events in Germany in June and July 1934 in which the Hitler regime brutally purged and murdered its internal opponents as well as critics outside the National Socialist Party. ↵

- Quoted in Glen McGregor, "The Gargoyle - 24 Sussex: 'The Crown jewel of the federal penitentiary system,'" Ottawa Citizen, 19 June 2015. ↵

- Quoted in Frank E. Manning, “Reversible Resistance: Canadian Popular Culture and the American Other,” in David H. Flaherty and Frank E. Manning, eds., The Beaver Bites Back: American Popular Culture in Canada (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993): 4. ↵