12.6 Building a National Identity

A British subject I was born — a British subject I will die.

– John A. Macdonald, 1891[1]

John A. Macdonald functions as something of an official repository of stirring and/or aggravating quotes. He spoke these words on the campaign trail in 1891 when the Liberals were arguing for closer economic ties to the United States. Evoking fear of annexation — economic certainly, political probably — Macdonald summoned up what he thought was core to being Canadian: British subjecthood. In Macdonald’s day and age, being part of the biggest imperial chain on the planet was something to boast about, and he was counting on other Canadians to feel the same way when he uttered this statement. He was, however, on the record as preferring a kind of arms-length colonial relationship with Britain in which the Dominion was utterly loyal but mostly autonomous. The Canadian High Commission in London was an expression of this: established in 1880, the High Commissioner represented Canadian interests in Westminster and to the Crown, a slight reversal of the role played by the Governors-General.

More than a century later, what is the national identity? Canadians are not “British subjects,” regardless of the fact that the Queen of Canada is also the Queen of Britain. It is difficult to imagine a Prime Minister today invoking that connection the way Macdonald did (successfully, by the way) in 1891. Was there ever a common agreement on that identity? No. The Provincial Rights movement of the late Victorian era eroded loyalty to the larger nation even as the Dominion struggled to establish its bona fides. Fealty to region did not end with Confederation; it survived throughout the 20th century, and not only in Quebec. A symbolic language of identity at odds with the national equivalent has consistently acted as a counterweight to the notion of Canadian-ness.

These debates and divisions are important to note because they all contributed to the building of national and provincial identities. In addition, they go some way to explaining why the history of Canada is so elusive.

Jack Little, a historian at Simon Fraser University, considers how early tourist accounts contributed to a national sensibility among Canadians.

Making Canada, Making Canadians

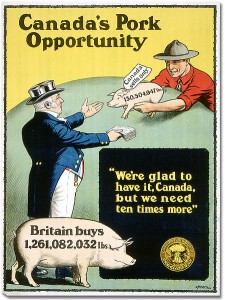

In the language of 21st century marketers, Canada had a weak “brand” at the start of the post-Confederation era. Was it a British colony or a free nation? The citizens were British subjects … which meant what, exactly, in Quebec? Was Canada a North American nation or an extension of the British Isles and, maybe, Western Europe as a whole? Such issues did not trouble the Americans who had nowhere to look but North America. They cut themselves loose from Europe in the 1780s and built their own continent-wide empire. The word patriot — which derives from the words pays and patris, thus meaning loyalty to the country of one’s father — was looked at askance in Canada because it was associated with American revolutionaries in the 18th century and the Patriotes of Lower Canada who led the 1837 rebellion against imperial authority. As well, for some more imperially-oriented Canadians, being a “nationalist” implied loyalty to the nation-state as a structure rather than to the larger ideals of the the empire, the Crown, and so on. The search for a common denominator, a shared bond that was both affectionate and inspiring was underway.

What was Canada in 1867 other than a collection of colonies? They’d fought no great battles together and, in fact, they’d sparred with one another from time to time. Adding on three more colonies by 1873 did nothing to change this. Settling and exploiting the West became something of a common project, although Westerners might argue that their disadvantages under the National Policy ought not be considered a source of national identity or pride. In the 19th century, the mechanisms for overcoming this alienation, or at least disinterest, were limited. There was no national media (unlike in Britain where The Times of London circulated widely) and there was no national education system (again, unlike in Britain); in point of fact, education proved to be one of the most divisive issues in the early days of the two Dominions.

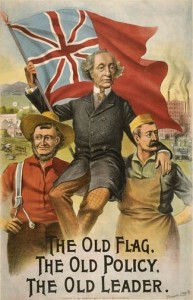

Imperialists jumped on adventures like the Boer War as a means of manufacturing national consciousness, much as English-Canadians had thrown themselves into the 1885 events in the West. While nationalists might call for a Canadian Navy, imperialists believed that a Canadian investment in the Royal Navy made the whole Imperial fleet a symbol of Canada. The persistence of royal imagery in these years suggests that Britain was a stronger source of icons than the Dominion itself. Certainly the monarch appears on Canadian postage stamps and currencies to the exclusion of any other leader until the 20th century. Other more Canadian traditions were, however, making an appearance. When Macdonald proclaimed himself a British subject forever in 1891, his campaign poster — “The Old Flag, The Old Policy, The Old Leader” — had him astride the shoulders of a factory worker and a farmer (both of whom look well pleased), brandishing a variant of the Red Ensign. The “old flag” in this case wasn’t the Union Jack after all, but a colonial model with the Union Jack prominent in the upper corner. The flag was far from “old” and using it in this way was meant to inspire a sense of Canadian tradition.

Artistic representations like this one cannot be underestimated as a source of Canadian identity and part of the process of what historians call “the invention of tradition.”[2] Posters were more easily mass-produced and more colourful than the photographs of the time, and the Post Office served as a distribution system. The Federal Government could issue these images, as could the national political parties. In fact, the Post Office itself, with a presence in almost every community of any size, was an instrument in shaping the Canadian idea.

Putting a Stamp on Canadian Identity

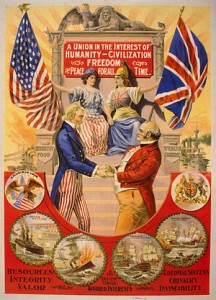

Across the Western world in the late 19th century, several strategies were exploited to build national sentiment in both new and old countries. Monuments and statuary were used in Germany, France, and the United States to good effect. Caricature icons also became a vehicle for people’s collective identity, such as “John Bull” for Britain and “Uncle Sam” for the United States. National holidays — the 4th of July in the United States, La Fête Nationale (aka: Bastille Day) in France on the 14th of July, the monarch’s birthday in Britain (celebrated in June since the 18th century), many “Independence Days” in Latin America, and countless saint’s days — constituted another convention and mechanism for identifying and rallying around a national storyline. Similar strategies were deployed in Canada, but with less grip.

Nationalist statuary in Canada is, for whatever reason, less dramatic and less effective than in other countries. Busts of royals show up everywhere, but there are few national heroes who got that sort of treatment before 1914 and even fewer after 1930 (see Alan Gordon’s discussion of “Monuments and Memory” in Section 12.12). There are, moreover, no enormous triumphal arches in the major cities, no equivalent to New York’s Statue of Liberty (1886), and — despite the importance of the Notre-Dame Basilica in Montreal — no national cathedral. Attempts have been made to create a personification of the nation in the form of “Johnny Canuck,” a sort of all-purpose character who appeared in newspaper cartoons and other visual forms from the late 1860s on. Typically, a fine physical specimen wearing a Mountie-style Stetson and riding boots, Johnny (sometimes “Jack”) Canuck (in these iterations at least) served as a counterpoint to John Bull and Uncle Sam (the former being corpulent and the latter what Shakespeare might call “lean and hungry”). Canuck, however, doesn’t appear to stand for anything — prosperity? freedom? ironic detachment? — and so hasn’t seen much action over the years. What’s more, there was no feminine equivalent: nothing to match Britain’s Britannia, America’s Columbia, or France’s Marianne.

Generally, national holidays have proved more durable and effective. The monarch’s birthday (now held on the 24th of May) was transplanted from Britain. Dominion Day (renamed Canada Day in 1982) was celebrated on the first anniversary of the British North America Act and every 1st of July thereafter. Labour Day followed and was officially recognized by Ottawa in 1894, even though it had been celebrated by trade unionists since 1872. (Saint-John-Baptiste Day is older than both, but it had a much rougher time acquiring government sanction and did not become a parallel national holiday until 1925.) Thanksgiving in Canada was an imported American event grafted onto existing celebrations of the harvest and was proclaimed a national holiday in 1879. These days off from work may not seem to have much to do with building Canadian identity, but they were an effective means of disseminating shared customs and practices (turkey dinners, parades and marches, and picnics in civic parks) to both established Canadians and newcomers who needed to be assimilated into the mainstream culture. Such tactics could be seen perhaps most clearly in Canadian classrooms. Even in the absence of a national education program, the infrastructure of schooling contained many secular images designed to promote a national identity. Portraits of the current monarch adorned most classrooms, as did maps that underlined Canada’s enormity. Well into the 20th century images of the current Prime Minister gazed down on rows of schoolchildren as well. In offices across the country, one could find portraits of Laurier or Macdonald — depending on whether the occupant was a Liberal or a Tory — long after the two statesmen were out of office, which is a symbol of the power of patronage and party loyalty more than a shared national character.

Another venue for disseminating a national identity was still more humble and assuming. The 1890s ushered in an era of unprecedented image-making expressed through postage stamps.”[3] Pre-Confederation stamps included images of a beaver and symbols of the British connection; these were followed, after Confederation, by three decades of stamps bearing the likeness of Queen Victoria. As a reminder of the country’s principal loyalties, this use of the Queen’s likeness was itself a powerful message. Then, in 1898, the first post-Confederation stamp without any relation to the Queen appeared, which was a map of the world in which Canada is prominent at its centre and the lands of the British Empire are highlighted in bright red. Thereafter, historic themes are gradually explored, including five commemorative stamps that appeared in 1908 to mark the tercentenary of the founding of Quebec City (and thus Canada and New France). Nothing more would be done on this theme until 1917 when a commemorative of the Charlottetown Conference of 1864 was produced.

A similar venue for imagery is the national currency. Paper currency was in circulation from before Confederation, and images of logging recur, for example, on the 1898 dollar bill. The more widely-circulated 25 cent bill — the “shinplaster,” so called because of its small size and square-ish shape — was, however, the preserve of royal imagery. The first coin minted in Canada did not appear until 1908. Like many of its contemporary bills and stamps, it featured a royal head (Edward VII) and — more subtly — a winding vine of maple leaves. In the case of both postage and currency, the appearance of “Canada” was itself a simple and subtle building block of national identity.

All of these modes of expressing and shaping a national brand experienced a boom in the 1930s as Canada gained greater independence from Britain, although some of the key elements had already been established. Royals, political leaders, and maple leaves were among the most favoured themes. The creation of the CBC shifted the symbolic language of national identity to radio waves; advances in photography and photographic publication in magazines and other documents were also important. Historians Ian McKay and Robin Bates have demonstrated how the provincial tourism industry of Nova Scotia took advantage of developments in printing to disseminate, within and beyond, images with strong historic reference points.[4] This process, which they call the “making of the public past,” created a new and arbitrary iconography. Parallels can be found in every province, examples of an emergent national consciousness at the regional level. McKay and Bates have demonstrated that this process introduces a shift in focus from “history” to “heritage”:

If both draw on the actual events of the past, history as such necessarily upholds a notion (however nuanced and qualified) that some stories about the past are better — more accurate, complex, verifiable, ethical — than others. […] Unlike history, heritage does not advance falsifiable positions, not even when it comes to us arrayed in the forms of history: “It uses historical traces and tells historical tales, but these tales and traces are stitched into fables that are open neither to critical analysis nor to comparative scrutiny.”[5]

Heritage speaks to group identity in a manner that History cannot. We hear references to “our railway heritage” or “our fiddle-music heritage” that are meant to evoke an inclusion (suggested by “our”) and, by definition, an exclusion (not everyone is “we” or “us”). In addition, heritage elevates an iconography of the past without problematizing conflict. “Our railway heritage” or “our prairie homestead heritage” looks very different to a Canadian of settler descent whose ancestors were given a quarter section of free land and another whose Aboriginal great-grandparents’ land was seized, carved up, and given away.

Such simplifications and mythologizing explain, in part, the durability in the Canadian mind of Anne of Green Gables, the Cariboo gold miner, the homesteader, Champlain and the heroic age of New France, and the Franklin Expedition. These are symbols that are comprised overwhelmingly of European faces and values, in which Aboriginal peoples are noticeably missing. Asian- and African-Canadians are similarly conspicuous by their absence. By creating a language of national heritage that excludes other stories, this focus on the Euro-Canadian narrative (invariably told as a narrative of success) eclipsed other possible identities and narrowed the possible stories available to be told.

Advancing these images and others became part of the national project (and parallel provincial and regional projects as well). The same processes occurred in other countries, and we continue to see these enterprises today, if we take the time to look.

Two Founding Nations

At the time of Confederation, there was little appetite in English-Canada (especially Orange Ontario) for a dualist vision of the country. Catholicism was regarded by many leading anglophones as treasonous, and French people were characterized as backward and superstitious. Anglophones and Protestants, by contrast, were regularly depicted as vital, aggressive, dynamic, and tough-minded. Anglicizing the West — the clearing away of the French-Catholic Métis — was not an accident, and French-Canadians generally were on solid ground when it came to fears of assimilationist intentions on the part of their neighbours. If the English-Canadians could not eliminate the French fact in reality, they would often do so symbolically. For proof one has only to remember the lyrics to Canada’s other national anthem, The Maple Leaf Forever, which thrillingly recounts the defeat of Montcalm by “Wolfe, the dauntless hero,” and the fact that the “thistle, shamrock [and] rose entwine the Maple Leaf” implied that the fleur-de-lis was not allowed to take its turn.

Listen to the original version of The Maple Leaf Forever.

Most often, nationalistic music excludes the foreign but, in the case of The Maple Leaf Forever, it actually excludes a core group of Canadians. As one specialist explains:

Rather than representing the nation as a whole and serving purposes beneficial to everyone, nationalist music acquires more specific functions, perhaps the dissemination of a restrictive set of ideological values or the aggrandizement of a ruling group or an elite oligarchy. Music presents the nation with a way of preserving its past and thus writing the history of its present…. By injecting nationalist sentiments into national music collections, scholars and government agencies alike ipso facto make room for some residents of a nation while taking away space from others.[6]

Dualism clearly presented problems when it came time to imagine Canada as a product. How to build it? How to maintain it? If the strength of the Dominion derived from its British traditions and military might, then how does one celebrate the culture of a different — and ostensibly defeated — culture? Military symbols were among the most powerful of the Victorian and Edwardian eras through to the Great War. It is no accident that the North West Mounted Police uniform is modelled on that of a British regiment in occupied Ireland: the red tunics announce Britishness. Moreover, the force was recruited exclusively from anglophone Canada. The Mounties are the symbol of Canadian authority par excellence in the West; read differently, they are evidence of intolerance for a dualistic national ideal.

And yet dualism emerged in the 20th century as the most durable of the national myths. “Two founding nations” has its roots in the BNA Act, which seeks to preserve French and Catholic institutions at the provincial level. The French-Canadians who negotiated the constitution argued that the provisions of the BNA Act would also enable the co-building by both French and English of a larger country. Anglophone contemporaries understood it differently: French-Canadian Catholicism was now corralled within one province where it would stay. Again, one may turn to the separate schools debates across the country in the pre-WWI era for evidence of how these two visions were mutually exclusive. Gradually in the 20th century, there opened up a little more tolerance in some areas, while in others the space for dualism closed further and faster.

Several landmark events fostered a growing nationalism that contained space for both French and English sentiments. The Great War marks a turning point in this respect, since it was a source of pride for Canadians with respect to the performance of the nation’s troops in the face of extremely grim circumstances and under what was generally thought to be poor British leadership. It was also divisive, however, in that the conscription crisis divided French and English Canada. There followed a series of events that both built on the embryonic patriotism fostered by the war and downplayed the contentious issue of conscription.

The first of these is the Halibut Treaty of 1923, an agreement struck directly between Canada and the United States without the involvement of Britain. Shortly thereafter, in the same year, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King attended the Imperial Conference in London, at which it was agreed that Commonwealth countries could now pursue their own foreign policy initiatives independent of the Empire. Effectively, this agreement put an end to the Canadian Imperialist dream except insofar as Canada remained an important part of a loose alliance of nations with Britain at the centre. These changes were enshrined in the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and the Statute of Westminster in 1931. In 1939, O Canada was officially declared a companion national anthem, alongside God Save the King/Queen — a symbolic but important change.

In these years as well, both the Liberal and Conservative Parties nationally took steps to reduce internal fissures between French and English elements. The Liberals enjoyed far greater success in this regard by adopting an informal or de facto policy of alternating leadership between English and French Prime Ministers.[7] Following the Second World War, it became possible for the first time to hold “Canadian citizenship” under new 1946 legislation. Finally, in the 1960s, three events occurred in close succession. Under the Pearson regime, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism was established in 1963, made a preliminary report in 1965, and concluded with a full report in 1969. Its existence and six years of work did much to change the tenor of nationalist discourse in the country. Coincidentally, the replacement of the Red Ensign with the Maple Leaf flag in 1965 was seen as a nationalist step that placed further distance between Canada and the Imperialist (implicitly anti-nationaliste) vision. Finally, the celebration of the centennial of Confederation in the form of Expo ’67 in Montreal was another step toward a thaw in English-Canadian attitudes toward dualism. The fact that this took place against a backdrop of growing French-Canadian nationalism and separatist feeling was, of course, ironic.

What is sometimes regarded as the genius of Pierre Trudeau was his ability to move beyond dualism to a multicultural nation state. This was an expression of the reality in Canada’s cities in particular, but also the West generally, which were home to a multitude of ethnicities for whom the French vs. English debate in central Canada was less and less meaningful. The nationalism of Bourassa (essentially a dualistic vision of Canada as a continent-wide home for French and English alike), the nationalism of Maurice Duplessis (which fostered a view of Quebec as French-Canada in its entirety and closed off from the rest of Canada), and the nationalism of the Diefenbaker-Pearson years (which espoused a “de-hyphenated” national identity) were thus superceded by a national pluralism in which multiculturalism was a dominant value.

Heritage Fare

In 1972 a popular CBC radio show host, Peter Gzowski (1934-2002), opened a competition to find a Canadian equivalent to the phrase “as American as apple pie.” The winning submission came from a Sarnia, Ontario woman, Heather Scott, who suggested “as Canadian as possible under the circumstances.” Generations that followed have been, on the whole, more or less content to agree. Indeed, the popular self-perception Canadians have is of a humble nation not given much to flag-waving, which is certainly a convenient place to land after decades of Union Jack-waving that only divided Canadians.

Yet the symbolic language of national identity continues to constitute a small industry. Every national monument or park, every backpack bearing a Maple Leaf flag, and every debate about Quebec’s place in Confederation (never English-Canada’s place in Confederation) is part of that discourse. So, too, are nationalistic uses of sports: lacrosse was declared the national sport in 1859 and demoted to “Canada’s National Summer Sport” in 1994 when hockey was elevated to a parallel status for winter. (The fact that the professional leagues in both sports play from autumn into late spring is evidently neither here nor there.) Olympic and other international competitions have been exploited for nationalistic momentum and examined by journalists and scholars alike for signs of “what it means to be Canadian.”[8]

The struggle to construct nationalisms leans heavily on history, and history has tended to serve nationalism. One need only think of early accounts of the NWMP/RCMP as a bold and venturesome extension of Canadian will — as opposed to a brutal and often clumsy and undignified imposition of foreign rule — for an example. As historians Laura Peers and Robert Coutts point out, as Canadian history has privileged the accounts of Euro-Canadian experiences, it has necessarily downplayed Aboriginal stories:

Prior to the 1980s, Aboriginal people were seldom mentioned in either scholarly texts or at historic sites; when they were, the discussions emphasized colonial control over Aboriginal people within historical narratives that celebrated the establishment of that control. Thus, the choice of sites, figures, and events for commemoration emphasized “great men” (such as explorers) and their discoveries, military forts as representations of the establishment of European control in a region, and technological advances associated with nation building such as water locks that facilitated shipping.[9]

In thinking about the history of Canada one must, therefore, make space for the history of the “idea” of Canada. Too often that gets bound up in notions of “Canadian heritage,” which it is not. What the concept of Canadian-ness has accommodated and left out tells us, as historians, a great deal about the society that people in the past thought they were building, and the place in which they believed they lived.

Lament for a Nation

One of the most powerful 20th century essays on the state of Canada appeared in 1965. Lament for a Nation was a social conservative reply to the decision reached by the Liberal government of Lester B. Pearson to host American nuclear missiles on Canadian soil. It was written by George Parkin Grant (1918-1988), a philosophy professor at McMaster University in Hamilton.

Grant took the position that human freedom is the end-goal of history. He maintained that Canada had a special role to play in that process by dint of being a North American country steeped in French and British political philosophical traditions, and yet distinct from the republic to the south with its powerful legacy of slavery. Continentalism was, in this respect, the enemy. Grant was alert to the changes in symbolic language that pointed in that direction: to him the loss of the Red Ensign flag was a signal that Canada was casting off one of the ropes that tied it to European perspectives. Like many Canadian nationalists, his vision of Canada was one that engaged globally and led internationally, rather than one tied to a North American economic engine: material wealth was less important to him as a measure of national greatness than engagement globally.

Lament was viewed at the time (and has been almost revered since) as a radical statement of Canadian nationalism in the face of creeping Americanism. Was Grant on the outside looking in? Or was Lament a manifesto of elite despair? Indeed, one can hardly imagine someone more entitled to the title “establishment figure” than George Parkin Grant. He was the grandson of two Canadian Imperialists: on his mother’s side George Robert Parkin and on his father’s side George Monro Grant. His mother’s sister, Alice Parkin (1880-1950), married Vincent Massey (1887-1967, of the Massey-Ferguson agricultural implement fortune) who became from 1952-1959 the first Canadian-born Governor-General. Raymond Massey (1896-1983), uncle Vincent’s brother, was one of the great Broadway and screen stars of the mid-century, a celebrity in his own right. Grant’s father and his mother’s father Parkin were both principals of Toronto’s elite private school Upper Canada College; grandfather Grant was president of Queen’s University. Historian, polemicist, and politician Michael Ignatieff (b. 1947) is the nephew of George Grant, an indication of how the value of a Canadian establishment pedigree continues to carry weight.

Exercise: History Around You

The Mountie always Gets his Man

Consider the noble Mountie. Strikingly clad in his scarlet tunic, astride his noble steed, the leather of his high riding boots and the jet-black of his thick belt. Atop his head is a cute pillbox hat tilted coyly to one side with a strap pulled tightly under his clean-shaven chin.

Wait, that can’t be right….

Yes, the earliest iteration of the Mountie uniform included a hat more usually associated with 20th century bellhops, elevator operators, cigarette girls, and car valets. Its successor was a white pith helmet (pith being another word for cork) that stood tall on the wearer’s head and which is mainly thought of today as having something to do with imperialists in the tropics and Africa. The flat-brimmed Stetson was the third-time-lucky alternative.

Does it matter? Perhaps. As representatives of Canadian authority in the West, there’s a reason why the Mounties looked like the Royal Irish Constabulary or a regiment sent in to suppress a rising in Rhodesia. These were the shock troops of Canadian imperialism and an expression of Anglo-Canadian virility. As a familiar icon of Canadian culture, how has this been used? How does it continue to be used?

In 1995 the image of the RCMP (and its predecessor the NWMP) was sold to the Disney Corporation. Canadians were outraged. Only a few years earlier, Constable Baltej Dhillon, a Sikh-British Columbian member of the force, achieved national notoriety when he won the right to wear his turban in place of the Stetson. A chorus of Canadians were equally outraged at that development as well. As historian Michael Dawson points out, “many people considered the Mountie to be an important national symbol” and, in some respects, an inviolate symbol at that. He adds:

Mythologies, like the one surrounding the Mountie, are instrumental in forming a cohesive bond of shared English-Canadian sentiment — a sentiment essential for English-Canadian nationalism given Canada’s proximity to the United States and the necessity of developing some response to an increasingly boisterous Quebec nationalism.[10]

Look at ways in which you encounter images of the RCMP and the archetypal “Mountie.” Consider the pose, the backdrop, the circumstances (royal visit, Canadian trade delegation abroad, opening of a public building), the material and medium (photograph, plastic doll, film, cartoon, music), and the typology of the individual Mountie (male, female, Euro- or Asian- or African- or Aboriginal-Canadian). What is the message being transmitted? What does it say about the force and/or Canada? Is it a national icon, a shorthand for Canada as a whole, or something satirical? If this is a part of the national identity, one based in historical traditions, then it deserves scrutiny.

Key Points

- The history of the nation must include a history of national images.

- Canada’s ability to generate coherent and widely accepted icons and symbols of the national character, values, and binding events has been challenged by divisive historical circumstances.

- There are many means of transmitting a nationalist message, including anthems, postage stamps, national holidays, and currency.

- Heritage and history get bound up in one another, as the former expresses common experiences that are meant to be unifying but are often insufficiently problematized from a historical perspective.

- Dualism grew through the 20th century as the dominant national trope, and was succeeded after the 1960s by multiculturalism.

Attributions

Figure 12.12

“Our Lady of the Snows” – A Strictly Canadian Character (Online MIKAN no.3622536) by Keystone View Co. / Library and Archives Canada / PA-207560 is in the public domain.

Figure 12.13

The Old Flag – The Old Policy – The Old Leader [Sir John A. Macdonald] : 1891 electoral campaign (Online MIKAN no.2834401) by Library and Archives Canada, C-006536 is in the public domain.

Figure 12.14

The Great Rapprochement by AnonMoos is in the public domain.

Figure 12.15

Canada’s Pork Opportunity by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.

Figure 12.16

Green Gables House front view by Markus Gregory is used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license.

Figure 12.17

Police Fort Walsh 1878 by Jean Gagnon is in the public domain.

- John A. Macdonald, from 1891 election campaign speech: “As for myself, my course is clear. A British subject I was born — a British subject I will die. With my utmost effort, with my latest breath, will I oppose the ‘veiled treason’ which attempts by sordid means and mercenary proffers to lure our people from their allegiance.” Macdonald opposed the US commercial treaty proposed by the Liberals. ↵

- Eric Hobsbawm, “Introduction: Inventing Traditions,” in The Invention of Tradition, eds. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 1-14. ↵

- Eric Hobsbawm, “Mass Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914,” in The Invention of Tradition, eds. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983): 281-282. ↵

- Ian McKay and Robin Bates, In the Province of History: The Making of the Public Past in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010). ↵

- Ibid., 15. ↵

- Philip V. Bohlman, World Music: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 94, quoted in Robin Elliott, "Maple Cottage, Leslieville, Toronto: (De)Constructing Nationalist Music History," Institute for Canadian Music Newsletter, ISSN 1705-1560, accessed June 22, 2015, http://sites.utoronto.ca/icm/0101b.html#n30. ↵

- However, there is some slight of hand involved in this alternation. While it is true that Laurier was succeeded by King, St. Laurent was not King’s choice -- he would have preferred his Finance Minister Douglas Abbott (1899-1987), an anglophone from Montreal. Following St. Laurent, Lester Pearson’s rise was meteoric, given the Nobel Prize for Peace, so it is difficult to imagine any other contender at the time from any part of Canada becoming PM. In addition, while Pierre Trudeau’s ascent was also dramatic, it is easy to forget that the field was made up of many credible candidates and that the leadership convention vote went to an unprecedented four ballots before Trudeau won 50.9% of the vote against the now entirely forgotten Bob Winters (1910-1969) who had a very credible 40.3%. ↵

- If I sound cynical on this score, it is only fair that you should know that I am wearing a Canadian soccer jersey in support of the women's team in the 2015 World Cup. ↵

- Laura Peers and Robert Coutts, “Aboriginal History and Historic Sites: The Shifting Ground,” in Gathering Places: Aboriginal and Fur Trade Histories, eds. Carolyn Podruchny and Laura Peers (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2010), 276. ↵

- Michael Dawson, The Mountie from Dime Novel to Disney (Toronto, ON: Between the Lines, 1998), 1-5, 25. ↵