4.3 Succession Planning

Finding a successor was Macdonald’s last great challenge, and it was to prove his greatest failure. The 1891 election saw a 76-year old Macdonald out-campaign the 50-year old Wilfrid Laurier, but the Conservative victory was narrow and the Tories were thoroughly beaten in Quebec. Macdonald’s health, already taxed, began to fade and yet at that moment his political heirs proved to have feet of clay.

Langevin’s reputation for corruption sabotaged his own chances; Ontario’s D’Alton McCarthy (1836-1898) was, at one time, a likely successor but he was emerging as the nation’s most passionate and vitriolic opponent of everything French and Catholic; Charles Tupper (1821-1915) — a Nova Scotian father of Confederation — might have done the job five years earlier but he, too, was in his 70s and also felt strongly that the mantle should go to a francophone; another capable Nova Scotian, John Thompson (1845-1894), was hated in much of English Canada because he had converted to Catholicism. John Abbott (1821-1893), the Conservative leader in the Senate, eventually took the job, even though Macdonald thought him unqualified. Worse, he was old. Abbott was 70 when he became prime minister, was forced from office by brain cancer less than two years into his term, and died months later. Bad luck continued to dog the Conservatives when Thompson reluctantly took the job, and then followed his predecessors to the grave when he died in office, suddenly, at 49 years. Another septuagenarian, Senator Mackenzie Bowell (1823-1917), became prime minister from 1894-1896; however, his cabinet turned against him and brought in Charles Tupper. Before Tupper could be sworn into office, his government was thrust into an election that he was destined to lose. Tupper would serve for 69 days – still the briefest tenure of any Canadian prime minister.

From 1867-1893 there had been only two prime ministers: Macdonald and Mackenzie. From 1893-1896 there were five, including Laurier. Failure to plan for life after “Old Tomorrow” badly damaged the Conservatives. They would rebound under the leadership of Robert Borden (1854-1937) in 1911, but the structural damage they had sustained would endure for another century.

Macdonald’s Legacy

Macdonald is something of an enigma in Canadian history. His impact is undeniable and, as the founding father, he is sometimes treated as something like a national hero. But he was ruthless in his politics and unsparing when it came to winning. His decision to starve western Aboriginals after they had signed treaties, so as to bring them into what he saw as a position consistent with the letter of the treaties, was simply brutal. While one may find quotes from this long-serving politician that display admiration for First Nations, his actions speak louder still. It is difficult to judge the extent of his corruptness in politics because the standards of the time were so slippery. Patronage was expected and even the buying of votes was winked at. However, the Pacific Scandal was not, and nor would the public have appreciated the Kingston dry-dock deal, had Macdonald lived long enough to see it exposed fully. And yet he was skilled at achieving a kind of political stability that was, arguably, necessary for a young country.

His relationship with Britain was not straightforward either. Macdonald saw Britain and the imperial connection as a necessary counterweight to what he regarded as a genuine American threat. Keeping in mind that Macdonald was the Province of Canada’s Minister of the Militia during the Fenian War, and that he carried a gun against the Upper Canadian rebels of 1837 (who he regarded as American-inspired republicans), when he said that “The Yankees are very bad neighbours,” he meant it. At the same time, Macdonald wanted greater independence for Canada and was mistrustful of British motives when it came to North American diplomacy and treaties.

Macdonald did much that our generation regards as bad, some of which we can contextualize and mitigate by saying that most of his peers at the time likely felt much the same way or would have acted the same way. He was a racist (privately and publicly) and that was quite common at the time. But in other instances he was found lacking in some ethical or personal spirit by his contemporaries, and that is something to which we must pay some heed. The situation in the Northwest in 1885 was one such situation where Macdonald’s approach to the First Nations’ complaints and the fate of the Métis was sharply criticized. Macdonald clearly had a compromised moral compass. One of his biographies states, “if Macdonald thought of the ends, he was insufficiently concerned with the means.”[1]

And, famously, he had a fraught relationship with alcohol and sometimes he was a reckless (though seldom, if ever, an ugly) drunk.

In 1886 John, his wife Agnes, and their daughter Mary decided to tour the West. Macdonald had served as the Member of Parliament for Victoria in the early 1870s — a safe seat that he needed when he lost his own Kingston riding, one that he could pick up because of the two-week-long elections of the era. But he had never been west of Ontario, and he wanted to catch a glimpse of the country he had annexed. Macdonald did what generations of 70-somethings would do from the 1880s to the present: he booked a railway tour. The family stayed in railway hotels, measured up towns like Calgary (promising), New Westminster (wouldn’t give it a second night), and Vancouver (burnt to the ground six weeks before their arrival), and they admired Mount Baker at sunset. As their train passed through the Rockies, Agnes came up with the idea that they ride on the very front of the engine, on the cow catcher. They did so and the story goes that they covered 200 km in that position.[2] It is a trivial thing and of no real matter to the political history of Canada, but it has to be said: It is difficult to imagine very many of Macdonald’s successors doing the same.

Exercises: Documents

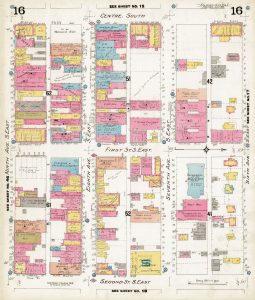

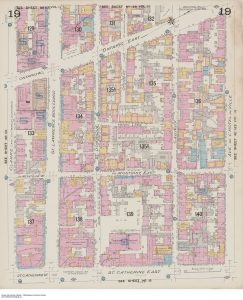

Fire Insurance Maps

Long before there was Google Earth, there was the fire insurance map. It’s one of the most useful documents for anyone interested in the shape of neighbourhoods of the past. Every structure, no matter how small, is identified, along with details like height, use, building materials, and — in the case of industrial buildings — the number of employees. Out-buildings like stables and even outhouses — toilets — are included, too. Fire insurance maps also tell us, right off the top, that fire insurance was now a thing, and that selling fire insurance had emerged as a job. The City of Vancouver Open Data Catalogue will provide guidance on how to read them.

Consider the three examples here. What kinds of historical questions can be answered by closely analyzing this type of primary document?

Key Points

- Macdonald’s legacy as a politician and a long-serving prime minister includes his failure to plan effectively for the long-term success of the Conservative Party.

- His politics were highly flexible, morally slippery, and mostly effective.

Attributions

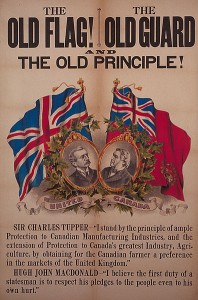

Figure 4.6

The Old Flag! The Old Guard and the Old Principle! by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain. This image is available from the McCord Museum under the reference number M967.128.1.

Figure 4.7

Advertisement for Molson’s Ale by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain. This image is available from the Library and Archives of Canada under the reference number 1996-278-2.34.

Figure 4.8

Lady Susan Agnes MacDonald (Née Bernard) (Wife of Sir John A. MacDonald) by Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada is in the public domain. This image is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reference number PA-025530.

Figure 4.E1

Insurance plan of Calgary, Alberta, October 1911, v.1. Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 3805540 is in the public domain.

Figure 4.E2

Vancouver’s Chinatown, 1897 (revised June 1901) Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 3807867 is in the public domain.

Figure 4.E3

Downtown Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Volume 1, Apr. 1909, revised June 1914. Library and Archives Canada / 3825720 is in the public domain.

- J. K. Johnson and P. B. Waite, “MACDONALD, Sir JOHN ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed 25 August 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_alexander_12E.html. ↵

- Ged Martin, John A. Macdonald: Canada’s First Prime Minister (Toronto, ON: Dundurn, 2013), 173-4. ↵