2.5 Canada Captures The West, 1867-70

George Brown entered into a coalition government with John A. Macdonald and George-Etienne Cartier in the 1860s with a grocery-list of conditions. One of the Toronto newspaperman’s demands was that Canada — in whatever form it was to take — would annex Rupert’s Land. There was no talk in 1867 — no serious talk at least — about adding British Columbia to the mix. After all, as the crow flies, Victoria was as remote from Toronto as British Honduras; a sea voyage to New Westminster from Halifax could take months.

The relationship between the West and the core elements of the Dominion of Canada was complex. They had a history together and it was sometimes invoked to justify the extension of Canadian control into the Northwest. But that history was not straightforward and the Canadians tended toward the simplest understanding imaginable: the West had been British and, as of 1870, it simply belonged to the Dominion.

French traders, explorers, and diplomats had ventured into the southern regions beginning in the 1730s. After the Conquest of New France in 1763, there was a struggle for control of the southern and western fur trade — a struggle that was eventually won by the North West Company (NWC). The Montreal-based fur trading consortium pressed further westward and aggressively extended its commercial reach. By 1812 the NWC had established posts throughout the Interior of what would become British Columbia, and was operating a network that reached the Pacific Ocean. Nine years later, however, the Canadian firm was forced into a merger with the larger, older Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), the commercial monopoly incorporated in London in 1670. The HBC claimed exclusive right to trade across the northern half of the continent, in “all the lands draining into Hudson Bay.” This territory, called Rupert’s Land, includes what is now northwestern Quebec, northern Ontario, eastern and northern Manitoba, the northern two-thirds of Saskatchewan, the northern half of Alberta, and almost all of Nunavut. The merger gave the British firm effective trading, and nominal administrative control over everything north of the 49th parallel and all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

By the 1860s land in Ontario was becoming scarce, and the same was true in the Dominion’s three other founding colonies. Young families were, consequently, migrating out of Canada and into the United States where land was as yet abundant and effectively free. Grafting the West onto Canada — and, in particular, onto Ontario — would mean free land for generations. Obtaining Rupert’s Land from the HBC would also reunite this economic hinterland with its old commercial metropolis in the St. Lawrence (in effect, reversing the consequences of the 1821 corporate merger).

The diversity of nationalities and syncretic cultures arising from a fur trade society is a feature of the utmost importance to the history of Western Canada. Most of the people in the Red River Settlement — what would become the core of the new province of Manitoba — were Métis. They were the genetic heirs of Europeans (mostly French-Canadians but also, French, Swiss, and Scots) who traded out of Montreal from the 18th century on. They were, as well, descended from a range of Aboriginal cultures, especially Anishinaabe (aka: Saulteaux), Cree, and Assiniboine but also Chipewyan and others. Culturally, they were more than the sum of their ancestral parts: the Métis were a “new nation” with their own dialect, economic practices, organization, and values. Catholicism was an important part of the mix and many Métis demonstrated an easy ability to move from the bison hunting society to the parlours of Montreal and back again. As the 19th century advanced, however, their awareness of their different-ness (the fact that they were related to, but not identical to, their Aboriginal and European neighbours) grew stronger.

Another group, described by historians as the “country born,” was also significant in numbers around Red River and to the north. This community was the product of intermarriage between HBC employees (mostly English and Scottish men) and Chipewyan, Cree, and Anishinaabe women. Their journey to a truly syncretic culture was different from that of the Métis. They tended to be Anglican or Presbyterian in their religious beliefs, usually spoke English, and were not part of the Plains culture of the bison hunt. While some were, for all intents and purposes, Aboriginal, others were de facto Europeans.

Through the 1860s, Anglo-Canadian expansionist ambitions would inform relations between the West and Canada. In 1864 at the Charlottetown Conference and again at the Quebec Conference, the prospect of an expansive and clearly imperialist Canada dominating the West was promoted. The desire of Franco-phobes like Brown to encircle and overwhelm Quebec with Anglo-Protestant populations was no secret. Toronto-based advocates agitated for annexation of the West, many of them with an outspoken assimilationist agenda. Quebec francophones, for their part, weren’t opposed to annexation, but they feared that Anglo-Protestants would interfere in what should be a reunion between two branches of the Franco-Catholic family.

In 1867, London was getting ready to divest the HBC of its trade monopoly and administrative role in Rupert’s Land. At the same time, the Americans were in an annexing mood. As far as the Canadians were concerned, time was of the essence; the timeline of Canadian expansion into the West would need to be brought forward. As far as the Métis majority at Red River was concerned, they had some important choices to make, and they felt strongly that these choices were theirs alone.

Historical accounts of relations between the Métis and the country born are sometimes contradictory, no doubt because every attempt to draw a composite picture is complicated by the existence of numerous and compelling exceptions. Sectarian boundaries were probably more critical in the mid-19th century than language, and persistent Scottish-French sympathies complicated things further. Broadly speaking, however, Westerners of Anglo-Protestant heritage viewed themselves as politically on the ascendant, mainly because of increased Anglo-Canadian interest in the region. This led to significant divisions among the Métis and Country Born communities of the Red River. Other historical interpretations have the two communities more fully recognizing their shared interests as they were increasingly subject to the rising racism boiling out of Canada West. Certainly, this was the dawn of modern racism: increasingly, what Anglo-Canadians saw when they looked at the country born were inferior “half-breeds” rather than co-religionists or champions of Anglo-Celtic culture. As for the the Métis in these years, the Anglo-Canadians only had more contempt for them.

The community would, in 1869, resist Canadian annexation and demand provincial status. Red River was daring in some respects. It had grown dramatically in the 1860s, but only to about 12,000 people (about one-eighth the size of Prince Edward Island). The majority was still Métis, followed by Scots and country born, but many of their neighbours were Ontarian Anglo-Protestants drawn by the promise of cheap land and the prospect of being pioneers in the colonization of the West by English Canada.

The West Resists

The relationship between the people of Red River and the HBC was far from straightforward. The company was an important source of imported goods and a source of revenue. It had acted for years as the local administration. Many of the local residents were former HBC employees, some of them retired from work much further north. In some respects the HBC was exploitative and put its own interests first; in others, it was a benevolent and paternalistic firm that had invested nearly 200 years in the region. Suddenly that continuity was broken.

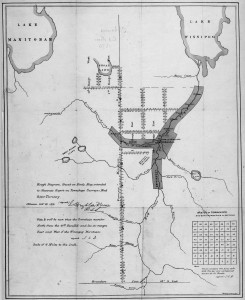

In the 1860s, Canada began a campaign to win Rupert’s Land away from Britain. Westminster was happy to cooperate. The HBC’s monopoly (which was, from 1849, more myth than reality) was purchased for £300,000, and administrative control of the region was passed to the Dominion government. Certain conditions applied. The Canadians had to negotiate treaties with the Aboriginal populations before the deal would be formalized. Ottawa proved far too hasty in this respect and others. Lieutenant-Governor William McDougall (1822-1905) was appointed even while the HBC Governor of Assiniboia, William Mactavish (1815-1870), was still in charge. The Canadians sent in land survey teams to redraw the map of the Red River settlement using the section and quarter-section block system, which ran lines right across existing colonists’ farms; all of these older farm lots were arranged along the riverfront in long narrow strips, as was the case under the seigneurial system of New France. This upset the Métis and it alerted the country born and Scots that their rights were not secured. The surveyors were duly chased out of the colony. No consultations took place between Ottawa and the Red River colony, which further inflamed local opinion. And, of course, no attempt was made to address the issue of treaty negotiations.

Events proceeded quickly. Only a month passed between the Rupert’s Land deal and the creation of a Provisional Government in Red River. Days later, at the end of December 1869, Louis Riel (1844-1885) would become its president. Riel’s father (Louis senior) was himself a Métis lawyer and leader who played a key role in the 1849 Sayer Trial. Julie Laginmonière, Louis junior’s mother, was part of the French-Canadian community at Red River. She provided connections with relations in Montreal to whom Riel would later turn. Young Louis grew up in the French parish of St. Boniface opposite modern-day Winnipeg, and had an interest in joining the priesthood. He travelled to Montreal in the 1860s to study, fell in love, became engaged, and then found himself jilted because the Canadienne woman’s parents were intolerant of Riel’s mixed-race ancestry. Depressed and perhaps heart-broken, he abandoned his studies and returned to Red River when his father died in 1864. Riel’s familiarity with the Canadians, his ability to conduct himself credibly in English, and his apparent intellectual ability made him a good candidate to lead the Métis National Committee. Photographs of Riel in 1870 show a man with broad shoulders and a large head; it is easy to overlook the fact that he was only 25 years old.

Ottawa regarded the Provisional Government as something akin to treason. The Canadians’ tactical errors, however, meant that their takeover of Rupert’s Land was to be stalled. In the absence of a legitimate Canadian claim, the sovereignty of the whole of the Northwest was now a grey area. The possibility that Riel’s government might take Red River into the United States stoked Canadian fears. At the same time, the Provisional Government’s proposals for provincehood for the Northwest were unacceptable to Ottawa. Red River was demanding the same kind of provincial status enjoyed by the four former British colonies that formed the heart of the Dominion. That included control over natural resource revenues. Ottawa’s perspective was that Red River had never been a British colony per se, and that the whole point of annexing the West was to enrich the Canadian project with resources, not to hand them over to the Métis in perpetuity.

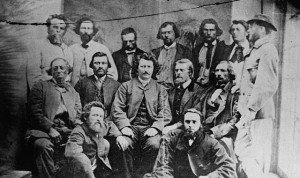

In Red River, there was an influential and potentially dangerous Canadian faction that plagued the Provisional Government. Riel and the Métis addressed the issue of community solidarity by doubling the size of the government and adding a number of English/Scottish/Country Born members to balance the Franco-Catholic representatives. The local Canadians, however, were unwilling to be brought to the table. Led by Dr. John Schultz, the Red River Canadians included recent arrivals from Ontario, and individuals who would benefit directly from Ottawa’s surveying contracts in the region. A brief skirmish led to the arrests of several in the Canadian Party, including a young Orangeman from Northern Ireland, Thomas Scott. By all accounts, Scott was toxic — a hateful, violent man fueled by an anti-Catholic rage. While all of the other Canadian prisoners were released in an effort to cultivate goodwill, Scott was executed.

The execution of Scott is seen by most historians as the turning point for Red River and Canada. While negotiations between the two governments became more fruitful, a public campaign calling for revenge for the “martyrdom” of Scott took off in Anglo-Protestant Canada. Clearly this would have ramifications for Red River, but it would also fracture the delicate relationship between Ontario and Quebec — only three years after Confederation. The Red River delegation was unable to secure resource revenue, but it did get provincial status for Manitoba and the promise that Métis’ and other existing farms in the region would be respected and registered. Amnesty for the leadership of the Provisional Government was not forthcoming.

Riel fled to the United States. Still a young man, he was restless and — as would become clear in later years — deeply disturbed by the events of 1869-70. He was so (rightly) fearful of being captured and murdered by Ontarian Orangemen, that much of his time was spent on the run. The Manitoba Act (1870) offered up the possibility of a dualist (French/English, Catholic/Protestant) province created by the federal government. For some Canadians this was a hopeful sign, but that hope would be dashed. The Canadian troops that arrived in Red River, hard on Riel’s heels, intimidated and brutalized the Métis population. Land registrations did not take place, and within a couple of years the core Métis population deserted the new province for opportunities further north and west.

Politics and Personality

Dr. John Christian Schultz (1840-1896) would emerge from all of this as one of history’s big winners. The creation of Manitoba gave him several stages on which to perform as a political leader. He was elected repeatedly (and always under suspicious circumstances) to Ottawa, was appointed to the Senate by Macdonald in 1882, and then became the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba in 1888. His motives are likely to be called into question, but Schultz’s record on Aboriginal (especially anglophone Aboriginal) affairs as an advocate is noteworthy. He even advocated for the Métis to some extent but remained a vocal opponent of Riel. Schultz’s rising star was entirely due to the displacement of the Métis from Red River and Manitoba’s resettlement by English-Canadians. As an out-rider of colonial power, Schultz demonstrated unwavering contempt for the First Nations at the outset, and then demonstrated the imperialist’s urge to act as their guardian once institutions were in place.

Key Points

- One of the objectives of the leaders of the confederation movement was the annexation of Rupert’s Land — the West — to enable the agricultural expansion of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

- Annexing Rupert’s Land was made urgent by the loss of population to the United States, and American interests in expansion in the region.

- The inhabitants of the West included the Métis, the country born, some Canadian migrants, and First Nations. Of these, only the Canadians were particularly interested in the prospect of annexation.

- The Dominion, in its haste, rushed administrative representatives into place (specifically, land surveyors) and it failed to negotiate treaties with the Aboriginal population. These errors would provoke reactions from the locals.

- Late in 1869 the Métis-dominated community at Red River established a Provisional Government and mounted a resistance to annexation. The local Canadian faction responded with attempts to subvert the authority of the government led by Louis Riel.

- The execution of Thomas Scott by the Provisional Government divided feeling in Ontario and Quebec, hardened Protestant Ontarian resolve to drive out the Catholic Métis, and sent Riel into exile.

- The Provisional Government’s negotiations with Ottawa produced the Manitoba Act and the colony’s willing entry into Confederation as a more-or-less equal partner.

Attributions

Figure 2.5

The Beginning of the Section Land Survey as Shown on J.S. Dennis’ Plan for the Survey of the Red River Plain (1869) by Wyman Laliberte is used under a CC-BY-2.0 license.

Figure 2.6

Councillors of the Provisional Government of the Métis Nation (Online MIKAN no.3194516) by Library and Archives Canada / PA-012854 is in the public domain.

Figure 2.7

Red River Expedition, Colonel Wolseley’s Camp, Prince Arthur Landing on Lake Superior (Online MIKAN no.2833387) by Library and Archives Canada / PA-012854 is in the public domain.