12.4 Political Recalibrations

There are many examples of regional political movements in Canada’s history, but most bought into the essential ideas and values of confederation. These were essentially “modern” qualities in that they were in support of the nation-state. The Parti Québecois challenged the legitimacy of one nation-state by proposing that Canadian federalism undermined the legitimacy of another: the nation-state of French Canada. The failure of the 1980 referendum and efforts to change the constitutional landscape seemed to address this, although by 1990, forces were at work in Canada that wished to challenge the very model of modernity.

The West Wants In

The near-disappearance in 1993 of the Progressive Conservatives and a poor result for the NDP ushered in a new era in Canadian federal politics. Conservatives — especially the more ideologically pro-business and socially conservative or “Blue Tories” — started shifting toward Preston Manning’s Reform Party. This move was especially the case in the West and BC; electoral success east of Manitoba, however, eluded Reform in the 1997 election, which was due partly to the populist stance of Reform that often pandered to the electorate’s cynicism and bigotry. Many of its MPs were on record as misogynists, homophobes, Francophobes, and racists, and the party expressly embraced neo-liberalism to an extent that surpassed even the Mulroney Conservatives.[1] Unable to expand its base, Reform was nevertheless able to form the Official Opposition in 1997. The former occupant of Stornoway, the separatist Lucien Bouchard, made way for Manning (b. 1942), the leader of a party that would rather see Quebec leave than agree to additional concessions.

By moving into Stornoway — something he promised not to do — Manning alienated himself from some of his erstwhile supporters. Further desertions came when he disciplined Reform MPs for making public statements that supported discrimination and endorsed limitations on individual rights based on race, sexual orientation, and health. The rise in the 1990s of the notion of political correctness provoked right-wingers within the party. Manning’s inability or unwillingness to take to task the more outrageously outspoken elements in Reform led to desertions from the party; at the same time, his half-hearted efforts to rein in the outliers led to other departures. One of the Reform Party MPs who disagreed with Manning on several fronts was a young representative from Calgary, Stephen Harper.

Manning’s call for a decentralized Canada in which all the provinces were inherently equal took several forms. Western Canada’s long-standing appetite for Senate reform was a key measure, taking the form of a Triple-E Senate — elected, equal, efficient. Reforms like this were aimed at dismantling the effective stranglehold that Quebec and Ontario had enjoyed in Canadian politics for more than a century.[2] Without central Canadian support, however, the Reform Party was going to be forever mired in the Opposition benches. The solution that Manning sought was a fusion of conservative elements into one party.

The merger of the Tory and Reform parties was accomplished in 2000. The right-wing or “blue” elites in the Progressive Conservative Party joined with Manning’s Reform supporters to form the Canadian Conservative Reform Alliance. (This party name lasted for only one glorious weekend as journalists from one end of Canada to the other noticed that if you added Party, the acronym became CCRAP.) Thereafter, it was the Canadian Reform Conservative Alliance (CRCA) and, in October 2003, the party of Macdonald, Borden, and Diefenbaker officially merged with Reform to produce the Conservative Party of Canada. Gone was Progressive, and in the next year, former Reform MP Stephen Harper was elected leader.

Not everyone in the old Progressive Conservative Party supported this move. Joe Clark was one of many old, and very often “Red” Tories who could not support the new CPC. The Progressive Canadian Party appeared in 2003 or 2004 as a vehicle for some of the disenchanted Tories who feared the loss of a particular kind of conservatism in Canadian politics. Its impact has thus far been inconsequential.

Politics as Performance Art

Small and even self-consciously absurd political parties appear from time to time and are a feature of many parliamentary democracies. Examples include Britain’s Monster Raving Loony Party and Australia’s Deadly Serious Party; for several years in the 1970s, Vancouver’s civic elections featured The Peanut Party led by Mr. Peanut (alias Vincent Trasov), which was supported by an all-woman dance troupe called the Peanettes. Satirical or joke parties serve several purposes, some of them not intentionally. They draw attention to the political process, even if they are criticizing its weaknesses. Assuming they succeed in making voters laugh, they read the mood in the country and measure what the electorate regards as worth satirizing.

The Rhinoceros Party (Parti Rhinocéros) has been the most successful and enduring of the joke parties in Canada. It was established in 1960s Montreal as a means to satirize political campaigns and political promises. They declared war on Belgium (because the Belgian comicbook character, Tintin, killed a rhino); promised to switch the right-of-way on Canadian roads from right to left (but this would be phased in gradually, starting with large tractor-trailer trucks first, followed by buses, smaller cars, then — last — bicycles and wheelchairs); and threatened to hold an inventory of the Thousand Islands to see if the Americans had filched a few. The party briefly went dormant in the early 1980s when a Montreal-area candidate, Sonia “Chatouille/Tickle” Côté finished second in her riding, ahead of the NDP and Tory candidates. The shock of a near victory passed, but the Rhinos were effectively barred from further involvement in federal politics by new laws in 1993 that required a $1,000 deposit and no fewer than fifty candidates to enjoy official party status.

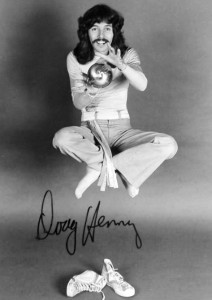

Founded on the ideals of transcendental meditation, the Natural Law Party of Canada (NLPC) took the new regulations in stride and ran 231 candidates in 1993 in their inaugural election campaign. Magician Doug Henning (1947-2000) was a fixture in the party’s leadership and an exemplar of “yogic flying.” Natural Law never presented itself as satirical; in fact, it sometimes seemed to take itself too seriously. Nevertheless, it was so far out on the fringe as to add welcome relief in an election that was otherwise (rather typically) mean-spirited. The Party’s share of the vote topped at about 0.63% and thus it never really got off the ground.

Not Easy Being Green

While parliamentary democracy allows for peculiar joke parties, it is also somewhat receptive to new — serious — political movements. Small but growing in ambition and support is the Green Party of Canada. Established in 1983, it was initially a federation of like-minded local activists that has evolved into a fully-functioning national organization with provincial wings. Setting aside its advances in the 21st century, the first 20 years of its existence produced little in the way of material results. No candidates were elected, and the party organization effectively went to sleep between election campaigns. In 2000 the Green share of the vote passed 0.81%, and four years later it was 4.3%; it would take until 2011, however, for the election of the first Green MP.

Canada’s political culture has several very deep and widely understood primary themes, one of which is the expectation that political parties offer different visions of economic growth. It might be agricultural or industrial, central Canadian versus “regional,” short-term or long-term, protective or free-trade, but there is always this note that must be struck by competing parties — a promise of more jobs. In this respect, the Green Party struggled in the 20th century insofar as many of its fundamental platform planks have to do with restricting unbridled economic growth, reducing environmental damage by reeling in resource exploitation and manufacturing, and planning urban growth more carefully. The century closed, however, with the growing realization that human-induced climate change is a reality and that environmental concerns are no longer the monopoly of single-issue activists.

Like the NDP, which is a member of the Socialist International, the Greens belong to a worldwide family of parties with a common list of objectives — the Global Greens. It is worth noting that there are no parallel organizations for Liberals or Conservatives.

Key Points

- Changes in the political landscape in the post-Cold War years include the rise of the Reform Party (which eroded the Tory base in the West) and the eventual disappearance of the PCs into the new Canadian Conservative Party.

- These changes brought Blue Tories into an alliance with Albertan conservatives whose populist politics were informed by Christian fundamentalism and a deep-seated mistrust of central Canadian elites.

- The structure of Canadian parliamentary democracy allows for the appearance, from time to time, of fringe and new parties that illuminate the limits of the existing political order.

Attributions

Figure 12.10

Doug Henning 1976 by We Hope is in the public domain.

- David Laycock, “Populism and the New Right in English Canada,” in Populism and the Mirror of Democracy, ed. Francisco Panizza (London, UK: Verso, 2005), 172-201. ↵

- Richard Sigurdson, “Preston Manning and the Politics of Postmodernism in Canada," Canadian Journal of Political Science 27, no. 2 (1994): 249-276. ↵