10.8 Canada Noir

Modernity brought significant social, cultural, and moral changes that not everyone was pleased to see. This produced a rolling tide of uncertainty and anxieties, some of which we refer to as moral panics. The temperance movement was rooted in moral panic, as were elements of eugenics. There was a succession of so-called “red scares” in the 20th century, beginning in 1918-19 with the Russian Revolution and followed by a year of general strikes in North America, a decade of unrest during the Depression, and Cold War fears of a nuclear apocalypse (which continued until the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989-91). Building a strong, moral, and disciplined nation that deferred to authority was the goal of many Canadian leaders. Many Canadian citizens did not fall easily into line.

Sins of the City

In a recent study of crime and society in early 20th century Halifax, Michael Boudreau makes the argument that Nova Scotian critics of modernity railed against the moral softening of an increasingly secular and ethnically diverse society. This was an essentially antimodernist position that looked backwards to a time of ethnic and spiritual simplicity. Their response to these conditions? Ironically, it involved a very secular and modernist agenda of government agencies, scientific police methods, and the employment of psychologists and other experts who could treat the criminal and the deviant.[1]

What was happening in Halifax was playing out in different ways across the country. In Vancouver, long-time mayor L.D. Taylor (1857-1946) repeatedly rebuffed morality crusades, proud of the fact that his city was not a “Sunday school town.” Vancouver’s middle-class voters, however, increasingly challenged his liberal view of “victimless crimes,” and in 1928 defeated him under the banner of “New Town, Not Blue Town.”[2] Taylor’s relaxed attitude was replaced by an increasingly bureaucratic administrative structure that, at best, talked a good fight. Modernist responses had to be made with the human resources available and many of the people involved in administrations, police departments, and morality crusades were every bit as compromised as the people they sought to change.

Modern society was urban, and urban life was a problem that needed solving. Cities, it was feared, were corrupting the morals and the very fibre of Canadians. Gambling, drinking, drugs, illegitimacy, and divorce — not to mention homosexuality — were dreaded, criticized, and policed from the 19th through most of the 20th century. Criminality was often understood in xenophobic ways that, for example, held the Chinese community responsible for gambling and opium; connected the Italian enclaves with violent crime, prostitution, and bootlegging; and connected Eastern Europeans, African-Canadians, and Japanese women with brothels. Indeed, the sex trade seems to have been widely regarded as a field into which Anglo-Celtics and Franco-Canadians could hardly hope to break. Eugenicists weighed into these conversations with their fears for the future of the race (most often meaning the British race), and alleging the corrupting moral influence of immigrants while pointing a finger at the decline of Canadian manhood (and, eventually, womanhood) through urban living.

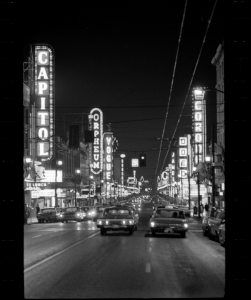

The goal of clean, safe, go-ahead, and ethical metropolises was elusive, however. Sometimes, it was easier to promote a different vision. Throughout the mid-20th century, Vancouver and Montreal in particular enjoyed reputations as cities in which sins could be serviced. Vancouver was the northern-most stop on an entertainment circuit based in San Francisco, then Los Angeles, and eventually Las Vegas, and which covered the western United States.[3] Vaudeville acts, musicians, and variety acts were mainstream elements in this network, but there was also a lively culture of strip-shows and burlesque. Night clubs and music hall-style theatres sprang up across the city centre; at one point, both Hastings Street (now the economically and socially depressed main artery of the Downtown East Side) and Granville Street were billed as the city’s “Great White Way” because of the enormous quantity of neon lights that blazed outside entertainment venues. The Cave, Palomar, Penthouse, Commodore, and Isy’s Supper Club (later, Isy’s Strip City) dominated what passed for the respectable trade, and between them offered thousands of seats most nights to audiences and diners. On the east side, showrooms and tiny venues jostled one another for space and offered a wide variety of entertainments. Because of restrictions on the serving of liquor, some of these clubs facilitated sales of bootlegged alcohol and provided hiding spaces under the tables for bottles brought in by customers. All had a reputation for keeping the local police happy with bribes. Some, more than others, provided a setting for the negotiation of the sale of sex. The combination of alcohol, sex, and music that had an African-American or Asian quality was viewed by critics as the triple-crown of immorality.[4] Sex and booze and ethnicity combined then to create a very artificial air of exoticism: the sense that this was something not of Canada but, at the same time, available only in Canada.

Montreal’s burlesque world was even more famous (or notorious) at the time, mainly because Canada’s largest city had a strong connection with both New York and Boston. Business elites of these American cities regularly travelled to Montreal, where they were treated to a nightlife that seemed genuinely foreign and risqué. Brothels, gin-joints, and gambling thrived through the first half of the century, mostly under the eye of Mayor Camillien Houde (1889-1958). Like Taylor, Houde was a populist, a man of the people, despite his snappy suits and glossy shoes. He supported fascists in the 1930s, opposed conscription and was branded a traitor by his English-speaking opponents, served time at Petawawa during WWII, and reemerged in 1945 more popular than ever. Under Houde, Montreal was an “open” city with limited restrictions on the sex trade, betting, and drinking. This was an affront to the sternly moralistic Union Nationale regime of Premier Maurice Duplessis (discussed in Section 9.9), and opposition to libertine Montreal grew through the 1950s. By 1955, a corner had been turned; brothels were being closed and other elements of the city’s entertainment industry were in peril. Houde stepped down and a new, more censorious era began.[5]

The timing of Montreal’s clean-up campaign roughly coincides with Vancouver’s. The Vancouver Police Department (VPD) had repeatedly found itself at the wrong end of corruption enquiries beginning the 1920s and continuing through the Depression into the postwar era. By the mid-1950s, it was clear that the rot extended to the Police Commissioner and included bootlegging, numbers running, and prostitution — all of which were being protected by the VPD. Effective opposition to such practices in both Montreal and Vancouver reflected the growing influence of a middle class committed to their small-l liberal vision of individual rights, the protection of property, the law as an instrument of morality, and professionalization of institutions like the police. They were motivated as well in the postwar era by those aspects of Cold War rhetoric that regarded anything that weakened the capitalist West as a victory for the Soviet East.

To some extent, then, the moral liberality that could be found in some Canadian cities before the 1960s was an expression of modernity and antimodernity at one and the same time. Its embrace of low-brow entertainments and rejection of law-and-order agendas, its refusal to be controlled by the state, its lust for non-rational fun, and its happy exploitation of differentness as a source of amusement — seen most graphically in the persistence of fairground freak shows but also in ethnic entertainments and slumming — is all directly descended from pre-modern practices. By the same token, these aspects of urban life could only be expressed in urban settings. Definitively modern cultural symbols like jazz and the blues, all-night restaurants, and cocktail lounges belong to this era.

So, too, did the tearing down of some of the racial and ethnic barriers that had been erected, ostensibly to protect mainstream and white society from what that society’s members considered as “others.” Chinatowns, like Vancouver’s (the largest in Canada), “represented otherness, crime, unleashed sexuality, opium dens, gambling, filth, run-down housing and mysterious back-alleys.”[6] As a neighbourhood, it was experienced by outsiders as a largely inhospitable place until it was exoticized in the 1930s. Thereafter the ribbons of neon light, and the late-night chop-suey houses and the nightclubs, provided a legitimate urban attraction while gambling provided a less legal alternative. At that point in time, the status of Chinatowns across Canada began to shift from civic eyesore to civic asset.

The experience of African-Canadians and African-Canadian communities was less straightforward. In the mid-20th century, performers like Oscar Peterson, Joe Sealy, and Eleanor Collins challenged colour barriers on both sides of the border with their extraordinary talents. But long before and well after the Civil Rights movement in the United States, African-Canadian neighbourhoods were regarded by civic and provincial leaders as problematic spaces where crime and lack of hygiene were issues. African-Canadians have thus been especially vulnerable to displacement from Canadian cities. “The Bog,” a Charlottetown neighbourhood near the city centre populated by an economically and socially marginalized African-Canadian community, was redeveloped out of existence around 1900. Vancouver’s 20th-century African-Canadian neighbourhood, Hogan’s Alley, was viewed by lawmakers and journalists as the scene of immorality, petty crime, and poverty; what locals regarded as a lively and vital community with its own African Methodist Church and businesses was bulldozed in the late 1960s to make way for a pair of highway overpasses. In both cases, the African-Canadian community never again coalesced; indeed, many of its members moved away for good.

Exercise: Documents

Les quartiers disparus

Often, historic artifacts document something other than what was intended. In the early 1960s, the City of Montreal was planning the Autoroute Ville-Marie, a freeway that would cut through the old downtown from one end of Île de Montréal to the other. This necessitated the removal of many buildings, homes, and businesses — along with their tenants — and the construction of large swaths of social housing. The City sent out a team to systematically photograph these spaces and residents before they all disappeared. A selection of these photos can be viewed here.

Start with the following three pictures. What looks familiar to you and what looks alien? If you were asked to document the material lives of 1960s Montrealers who were facing expropriation from their homes and offices, what could you glean from these photos?

Key Points

- Moral panics were a driving force in urban reforms in the mid-20th century, and the changes associated with modernism were among their many causes.

- Behaviour that had been tolerated in early generations increasingly came under scrutiny as middle-class city dwellers launched campaigns against gambling, drinking, drugs, the sex trade, and police corruption.

- Some cities were able to market themselves as entertainment hubs in which vices were actively promoted and ethnic differentness were presented in a positive light as exotic.

- By the mid- to late-1950s campaigns to clean up city life were carrying the day. Nightclubs were closing, ethnic “slums” were being erased, and corruption was being punished. It is worth noting that these changes took place precisely when the old downtowns were being abandoned for the suburbs.

Attributions

Figure 10.11

Sainte Catherine looking east at night by Conrad Poirier is in the public domain.

Figure 10.12

Anna Labelle, alias Mme Émile Beauchamp, tenancière, 1939. P43-3-2_V26_E271-01 by Archives de la Ville de Montreal is used under a CC-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 10.13

CVA 677-580 – [500 block of Carrall Street, looking north toward Pender Street] by Timms, Philip T. / City of Vancouver Archives is in the public domain.

Figure 10.14

Men on street in front of Sai Woo Chop Suey House at 158 East Pender Street by James Crookall is in the public domain.

This image is available from City of Vancouver Archives under the reference number CVA 260-452.

Figure 10.15

Montreal night life. Staff of 71 runs medium-sized Chez Paree club. Weekly wage bill is $3000 but earnings are higher as many rely on tips for bulk of income (Online MIKAN no.3615421) by Louis Jaques / Library and Archives Canada has nil restrictions on use.

Figure 10.16

Granville at night VPL 43347 by Vancouver Public Library Historical Photographs has no known copyright restrictions.

Figure 10.17

Viola Desmond by Hantsheroes is in the public domain.

Figure 10.E1

The expropriation of 856 rue Richmond, 17 May 1967.(VM94-C1023-038) by Archives de la Ville de Montréal is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 10.E2

Workers at Dominion Button Ltd. (VM94-C1027-084) by Archives de la Ville de Montréal is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 10.E3

Victoriatown, Montreal, 1963 (VM94C270-1114) by Archives de la Ville de Montréal is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

- Michael Boudreau, City of Order: Crime and Society in Halifax, 1918-35 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012). ↵

- Daniel Francis, LD: Mayor Louis Taylor and the Rise of Vancouver (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004), 150. ↵

- Becki Ross, Burlesque West: Showgirls, Sex, and Sin in Postwar Vancouver (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009). ↵

- John Belshaw and Diane Purvey, Vancouver Noir: 1930-1960 (Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2011). ↵

- William Weintraub, City Unique: Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and ’50s (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1996). ↵

- John Zucchi, A History of Ethnic Enclaves in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 2007), 9. ↵