7.7 Temperance and Prohibition

Alcohol consumption in Canada was prodigious in the early 19th century, and it hardly changed over the rest of the century. Any economy so heavily dependent on the production of wheat, rye, and other grains is going to quickly find a vent for surplus that involves fermentation. Some of the earliest and largest fortunes in both Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) were made in the brewing and distilling industries. Home manufacture was, of course, unregulated and widespread. The 19th century saw the growth of a movement culture around managing liquor production, sale, and consumption. It had many facets, and it was to prove the core movement around which many others revolved, and from which almost all 19th and 20th century reform movements would recruit their campaigners.

Drink Canada Dry

Rural drinking did not go unnoticed, nor was it without its critics. But it was different from what came after Confederation. Early attempts to “temper” or manage the consumption of liquor in British North America appear in the Canadas and the Maritime colonies in the 1830s and 1840s. These were “collective acts of individualism; each drinker who renounced the bottle was affirming the triumph of his or her will and the intent to meet the social and economic challenges that lay ahead.”[1] Viewed this way, pre-Confederation temperance was not a mass movement in that it was scaled down to the personal and the communal.

The late Victorian boom in city populations, however, propelled concern about liquor consumption to the forefront of public debate, and called for a mass and collective, rather than individualistic, response. As the economy came to value armies of men who could work in the resource-extraction sector or construction, the popularity of drink only increased. It is no coincidence that British Columbia, in 1893, boasted a resource-extraction economy with a severely distorted male:female ratio, and the highest per capita consumption of alcohol.[2] Nor should it be surprising to find that women’s consumption of alcohol increased in the Victorian era in step with the demand for single women in wage-labour. Wage earning, generally, was a critical element in the construction of a “wet” Canada.

So, too, was the environment. Urban reformers focused much of their energy on water quality issues for good reason. With horse manure carpeting town and city streets, pigs fouling the roads and streams, and human waste disposed of in haphazard ways, there was no way that urban water supplies would remain reliable for long. The situation in Nanaimo was probably not unusual. There, as early as 1864, locals were signing petitions about water quality issues. Household sewage was being dumped by the bucket-load on the streets. Two decades later, it was finding its way into a ravine or the harbour, where it was revealed on the shoreline with every low tide. Some went into an abandoned coal mine underneath the downtown. As was the case with most Victorian towns before the construction of sewers, a “night soil” scavenger collected human waste and removed it to a dump on the edge of town. And, of course, it wasn’t unusual for people to use human manure in their gardens.[3] In short, there were plenty of reasons to be concerned about the quality of drinking water; for many, the solution was tea or coffee (made of boiled water) or alcohol (germ free, available in a multitude of flavours, and often served in sociable surroundings).

Class and the Glass

The earliest and most constant critics of liquor consumption were the emergent Canadian bourgeoisie. Their liberal ideal of democratic progress and their dependence on effective employees made it inevitable that they would see liquor consumption and drunkenness as a threat to polity and productivity. One historian has argued that this economic and political agenda was complimented by the rise of evangelical Christianity across Canada in the mid-19th century. It wasn’t just that the Baptists and Methodists disapproved of liquor: their creed emphasized personal responsibility for redemption in a way that the established churches did not. It was, Craig Heron maintains, this constellation of forces that gave the Temperance Movement an appeal in Canada beyond what it enjoyed in Britain and the other Dominions; the movement was comparably strong in the United States as well, making this one of those cultural moments that has a continental complexion.[4]

If temperance had remained the exclusive preserve of the Canadian bourgeoisie, it would have gathered little momentum. But working people themselves were among the most vocal enemies of liquor. As a part of the community that sought greater inclusion in the political life of Canada and a better deal in the unfolding industrial era, artisans and craft workers articulated a view of respectability that denied alcohol a place in working-class culture. What is more, drink and a disciplined labour movement were incompatible. This was the position taken up by the Knights of Labor across North America (see Sections 3.4 and 3.6) and it was one that would echo through Canadian labour organizations into the 1920s.

The regulation of womanhood in the 19th century was also driving the emergent temperance movement. Maternal feminists based their claim for improved women’s rights and privileges on the strength of women’s reproductive power. In this context, women who drank to excess were jeopardizing themselves, their embryos, and the health of the nation. They were also undermining the claim made by the feminists of superior female morality. Historian Cheryl Krasnick Warsh has shown how the courts in late 19th century Ontario sentenced as many as 803 women in one year under drunk and disorderly charges; women’s share of convictions between 1881 and 1899 averaged 16% but ran as high 24% in 1895.[5] Women’s relationship with liquor was thus complex: increasingly dangerous, but at the very heart of an emergent feminist movement.

Another motivating factor at the turn of the century was the arrival of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. Here we see the collision of different cultures of drinking and the (largely Anglo-Protestant) Canadian fear of degenerate foreigners. Xenophobia, and prairie evangelism in particular, responded to the “threat” of foreign newcomers and their use of liquor, which simultaneously “eliminated the possibility of support from immigrants.”[6]

Exercise: Documents

Temperance Posters

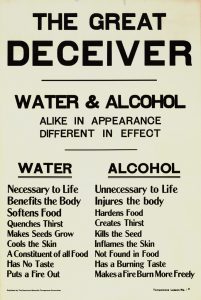

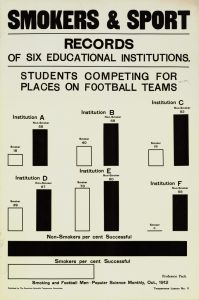

Consider the two pre-First World War posters promoting temperance (click on them to see larger versions). The first makes a subtle eugenicist case for temperance — can you see it? The other provides evidence that smokers don’t fare well when they try out for college teams. What’s wrong with those statistics?

Historian of the liquor economy, drinking, and the drys Craig Heron (York University) discusses temperance and the economic impact of liquor.

Temperance

Before the Great War, the focus of the temperance crusade was the local and not the federal level. The possibility of regulating the sale and consumption of liquor seemed reasonable to some, and in 1878, the federal government passed enabling legislation, the Canada Temperance Act, which enabled the local option of prohibition through referenda. Like all referenda, the local option effectively lifts from the shoulders of legislators the burden of making a choice on behalf of their constituents. It necessitates the involvement of the local electorate in direct decision-making around an ideal that has not been expressed in the form of a policy. (Members of Parliament debate actual bills that they can see and hold and on which they may offer editorial suggestions; referenda typically ask for general agreement on a broad principal without providing any of the details.) The likelihood of winning a national referendum on prohibition was slim but at the municipal level, it might succeed.

New Brunswickers seized upon the possibility of prohibiting public consumption of alcohol in the 1880s. Ten counties out of fifteen voted in favour of prohibition, and yet the sale of alcohol continued unabated. One study observes that “Moncton was, paradoxically, a prohibitionist town in which the liquor trade continued to flourish” from 1881 through the 1890s.[7] Enforcement issues plagued this experiment (as it would in many others); local police knew who was selling alcohol but were divided in their loyalties. One historian captures the situation perfectly: “relations between members of the police force and the liquor community were fluid.”[8]

No other province would advance the temperance campaign as far as New Brunswick until the 20th century. One reason for the failure of the “drys” to gain ground was the presence and power of the “wets.” Commercial distillers in Canada could be found among the wealthiest member-families of the elite. Seagram, Labatt, Molson, Keith, Wiser, Carling, O’Keefe, and — in the early 20th century — Bronfman are names associated even now with the alcohol industry, and with families who held powerful directorships in other industries (including banks and railroads) and had significant political influence as well.[9] They employed huge numbers of Canadians and, despite the reach of the CPR, local breweries and distilleries were also competitive and important economically until the 1920s.

Of course, not everyone in the middle or working classes wanted to go dry. Working men, returning soldiers, and members of the non-evangelical churches were highly unlikely to favour diminished access to booze. Young middle class women who entered the workforce in large numbers in the Edwardian years, and during the war, were a catalyst in the development of relatively respectable drinking “lounges” and, thus, became another population opposed to temperance. But this was the face of public drinking; the consumption of alcohol in private spaces was also a target of temperance agitators, and that aligned the elites and many middle class households against temperance. Insofar as the ranks of prohibitionists overlapped with anti-Catholic forces, they drove the Catholic Church into the arms of the wets (although where they were unbothered by assimilationist Protestants, the Catholic leadership was as likely to be dry).[10] There were, too, voices raised against the state regulation of liquor as a worrying example of growing governmental power.

Prohibition

The efforts of the temperance movement peaked in 1914 and were stayed by the outbreak of war. Unwilling to fight on two fronts, the issue was put to one side until it became clear that the Great War was not going to be brief. Increasingly, the consumption of liquor at home seemed an offence to the sacrifice being made abroad. Concerns were raised about productivity as well (a familiar theme in temperance circles in the industrial age). Province-wide referenda were organized, and by 1917, prohibition had arrived or was on its way in every province but Quebec, where one could buy wine or light beers, but not hard alcohol (see Section 6.5). It didn’t last. Returned soldiers were upset that the country had gone “dry” in their absence and felt that they had earned the right to drink after months and years in the trenches of Belgium and France. Quebec and British Columbia were the first to abandon prohibition in favour of regulation and government-controlled liquor sales in 1921. Prohibition was lifted in three provinces and the Yukon Territory by 1921; it didn’t last much longer in Alberta and Saskatchewan, but it held on longest in the Maritimes. The Dominion of Newfoundland prohibited possession or drinking of liquor from 1917 to 1924.

Thereafter, the legal and illegal production of liquor in both Dominions exploded in an attempt to meet demand for the banned substance south of the border.[11] American prohibition continued until 1933, creating a smuggling industry in every West Coast, East Coast, and Great Lakes Canadian town within range of an American market. While the heaviest traffic passed between the vicinity of Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan there was also extensive illicit trade between the nominally-dry Maritimes and the whole American East Coast.

Rum-running was a feature of Vancouver’s black economy as well. The chain of Gulf and San Juan Islands provided some cover, as did the multitude of tiny bays and inlets around Puget Sound. Fortunes were made on the strength of boats that could outrun Coast Guard patrols and the RCMP.[12] East Coast smugglers eluded local officials by claiming they were shipping out consignments to the Caribbean islands when, in fact, they were headed to Boston or New York. There were accusations that the Newfoundland government, under Premier Sir Richard Squires (1880-1940), “had turned the Board of Liquor Control into a covert bootlegging operation, the profits from ‘private’ sales going into his political account.”[13] Inland smugglers thrived as well, including those in Madawaska County (aka: the New Brunswick Panhandle) and the Kootenays in southern BC; both were remote and lightly-policed areas with porous borders. On the West Coast, this was what one study calls “the respectable crime” and the ranks of rum-runners in BC included members of very well-placed families.[14]

Historical studies of rum-running mention women too often to suggest that their involvement was exceptional. The production of small quantities of home-brew liquor was almost certainly work that women did, but they also played frontline roles in the sale and delivery of banned cargo. One study explains that high unemployment rates in the Maritimes in the 1920s were more crippling for women than for men, a fact that propelled many single mothers — some of them, of course, war widows — into smuggling. A Mrs. Donnie Hart of Saint John stands as a good example: arrested no less than once every year between 1916 and 1924, she worked as a bootlegger in order to provide for her family.[15]

Prohibition combined several contradictory forces. It was a manifestation of democratic will, a case of state intervention in the economy, and it was instrumental in building up urban police forces as well. Simultaneously, it diminished the rights of the individual, curtailed urban enterprise, and made public policy of private morality. It was both a modern and anti-modern force (see Chapter 10). Both sides in this debate advanced the use and sophistication of modern advertising as they campaigned for, on the one side, hearts and minds, and on the other, dry throats and vulnerable livers. The campaign against liquor, then, introduces a panoply of historical themes. It also introduces many of the key players in other crusades.

The Language of Liquor

Given the central place of liquor in the social lives of Canadians (past and present), it is no surprise to find that the vocabulary around drinking is both extensive and potentially confusing. What follows is not an exhaustive list of terms. It is weighted towards west coast usages and, worse still, none of these words are used in the past or present with razor-sharp precision, but nonetheless it may be helpful.

Where:

Saloon – Generally a drinking establishment not attached to a hotel or restaurant, usually urban. There are few restrictions on standing or moving about, and probably not much in the way of food.

Pub or Public House – These were often attached to roadside inns and “milehouses” in the mid- to late-19th century. They provided drink by the glass, and in larger take-away quantities, and often served food as well. A few survivors from that era kept the term in use and then it was revived in the 1970s with the spread of faux pubs (essentially saloons with somewhat better food and design that mimics an ideal of English or Irish drinking establishments).

Beer parlours/taverns – 20th century; a regulated and licensed private establishment in which the public can drink beer by the glass; standing at the bar is prohibited in most provinces; there is usually not much in the way of food to soak up that beer. In British Columbia, there were for many years restrictions on women’s entry (they had to use the “Ladies & Escorts” door) to restrict heterosexual mingling and, ostensibly, the sex trade. In beer parlours until the late-20th century, moreover, patrons were not allowed to carry their drinks from one table to another. Attempts to do so promoted the command to “sit down and drink your beer.”[16]

Boozecan, Blind pig, Speakeasy – Colloquial terms for illegal drinking establishments. These were called into existence by the increasing regulation of drink from the late Victorian-era, and especially so during Prohibition. Even after Prohibition ended in Canada, there were illegal establishments that sought to evade repressive regulation.

Who:

Drys – Advocates for the limitation, if not outright prohibition, of alcohol production, sale, and consumption.

Wets – Opponents to the above. This camp includes people who wanted to drink and also the powerful brewers, distillers, and other representatives of the liquor interests.

Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – One of the largest and most effective anti-drink lobbies in Canada. Established in 1874, months after its first branch was announced in the United States, the WCTU emerged as a vehicle for contiguous reforms in public behaviour, the political environment, and social conditions.

Rum-runners – Vendors of alcohol (not just rum) who ship it illegally across provincial or national boundaries into territories where there are sanctions — like Prohibition — against the sale of liquor.

Bootleggers – Anyone who sells liquor illegally. This term is used in the past to cover the rum-runners but its domestic face, historically, was the couple who sold cheap homebrew off their back porch, and the taxi driver who augmented his income with deliveries of bottles to homes and hotel rooms.

Liquor Control Boards – Provincial agencies created in the 1920s to regulate post-prohibition drinking and alcohol sales. These all became a major source of revenue for provincial governments.

When:

Sundays – Highly unlikely. During the era of the six-day work-week, Sunday was the only opportunity working people had to enjoy rest and leisure. That meant, too, that drinking was most likely to be heaviest on Sundays. But this was a red rag to the Temperance Movement bull — doubly bad because it combined sin with the Sabbath. Sunday closing rules were subsequently introduced in the early 20th century, and survived in most parts of Canada until the 1970s and 1980s.

When it’s quiet – Music and performances of all kinds used to go nicely with a drink in the 19th century. Joe Beef’s Tavern in Montreal — like many others in the Victorian era — brought together music, dancing bears, gambling, boisterous debate, and drink; low-brow entertainments became so closely associated with public drinking that reformers targeted both simultaneously.[17] As Craig Heron puts it, “In English Canada, both before and after prohibition, the isolation of public drinking from music and other forms of entertainment undoubtedly stifled the growth of popular music and popular theatre in Canada, compared to what was seen in Britain and Ireland. Montreal’s nightclubs were a special case, where drink and music were allowed to co-exist and, coincidentally, where Canada’s most vigorous jazz scene developed. Canada’s booze legislation, then, contributed to the country’s international reputation as a coldly austere, culturally repressed country whose public cultural life matched its often forbidding climate.”[18]

What to Do:

Abstinence – The anti-drink advocates began their crusade with a call to abstain from drinking. It threw the responsibility onto the individual and, in the rhetoric of reform-minded Christianity, there were moral and eternal consequences for not abstaining. The parallel moment in the anti-drug movement of the last 30 years would be the “This is your brain on drugs” campaign, launched in 1987.

Temperance – If you can’t completely give up the booze then at least drink in moderation. This approach was adopted by many drinkers but by the 1870s, by fewer and fewer within the temperance movement itself. By that time, the movement had become more intolerant of drink and organizations like the WCTU called for all-out prohibition. Mid- to late-19th century temperance agitators moved the discourse around drink from a personal and individual level to a social level, and from moral consequences to social consequences; they argued that the impact of liquor extended far beyond the drinker.

Prohibition – Taking the social agenda a step further, the prohibition movement called for state intervention and the total eradication of liquor. Implicitly, this meant that the question of individual choice was resolved in favour of state and police authority. Prohibition meant that individual effort was insufficient and that moral consequences weren’t driving change fast enough: legal and financial consequences had to be brought to bear, and these could (and did) include jail time.

Teetotalism – Often misunderstood as “tea”-totalism, the teetotal movement was an expression of the abstinence movement in that it promoted personal resolve and self-restraint on the liquor issue rather than legal sanctions.

Seek the help of a professional – Fortunes were made during prohibition by the producers and vendors of so-called “medicinal” alcohol. Products containing small quantities of alcohol were marketed as bitters, cocktails, and energy drinks.[19] A cooperative physician or pharmacist might be able to supply what you need.

Key Points

- Alcohol consumption in Canada increased and became more obvious with late 19th century urbanization.

- The temperance movement gained extra force in Canada because of the parallel rise of the evangelical denominations, the support of working class organizations, the role of maternal feminists, and fears associated with immigrants from non-traditional sources.

- Temperance was initially implemented on a municipality-by-municipality basis. Provincial referenda followed in the Great War, at which time both Canada and Newfoundland mostly went dry.

- The end of Prohibition in Canada and its continuance in the United States created opportunities for rum-runners on every shoreline.

Attributions

Figure 7.E1

The Great Deceiver by Dominion Scientific Temperance Committee, Provincial Archives of Alberta, PR1974.0001.0400a.0011 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.E2

Smokers and Sport by Dominion Scientific Temperance Committee, Provincial Archives of Alberta, PR1974.0001.0400a.0011 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.12

One half mile of barmen along Yonge Street during the Prohibition parade (Online MIKAN no.3193202) by John Boyd / Library and Archives Canada / PA-072524 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.13

CVA 480-215 – View of liquor stills captured during Prohibition by Vancouver Police Department / City of Vancouver Archives is in the public domain.

Figure 7.14

StateLibQld 1 147135 Malahat (ship) by John Oxley Library is in the public domain.

Figure 7.15

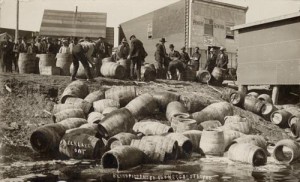

Raid at elk lake by C.H.J Snider fonds is in the public domain.

- Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, “‘John Barleycorn Must Die’: An Introduction to the Social History of Alcohol,” Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, ed. (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993): 12. ↵

- Warsh, “‘John Barleycorn Must Die’”: 13-15. ↵

- John Douglas Belshaw, Becoming British Columbia: A Population History (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009), 162-3. ↵

- Craig Heron, Booze: A Distilled History (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2003), 372-3. ↵

- Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, “’Oh, Lord, pour a cordial in her wounded heart’: The Drinking Woman in Victorian and Edwardian Canada,” Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993): 76-7. ↵

- Warsh,“’John Barleycorn Must Die’”: 16-17. ↵

- Jacques Paul Couturier, “Prohibition or Regulation? The Enforcement of the Canada Temperance Act in Moncton, 1881-1896,” Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993): 146-7. ↵

- ibid.: 156. ↵

- Derrek Eberts, "To Brew or Not to Brew: A Brief History of Beer in Canada," Manitoba History, 54 (February 2007), accessed 26 July 2015, http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/54/beerincanada.shtml. ↵

- Heron, Booze, 191-6. ↵

- Mark C. Hunter, "Changing the Flag: The Cloak of Newfoundland Registry for American Rum-Running, 1924-34," Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 21/1 (2005). ↵

- Daniel Francis, Closing Time: Prohibition, Rum-Runners, and Border Wars (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2014), 128. ↵

- Margaret R. Conrad and James K. Hiller, Atlantic Canada: A Concise History (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2006), 170. ↵

- Stephen J. Moore, Bootleggers and Borders: The Paradox of Prohibition on a Canada-U.S. Borderland (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 56. ↵

- Ernest R. Forbes, “The East-Coast Rum-Running Economy,” Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993): 168. ↵

- Robert A. Campbell, Sit Down and Drink Your Beer: Regulating Vancouver's Beer Parlours, 1925-1954 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). ↵

- Peter DeLottinville, "Joe Beef of Montreal: Working-Class Culture and Tavern, 1869-1889," Labour/Le Travailleur, 8/9 (Autumn/Spring 1981/82): 9-40. ↵

- Heron, Booze, 378-9. ↵

- Jason Vanderhill, "The Daniel Joseph Kennedy Story," Vancouver Confidential, ed. John Belshaw (Vancouver: Anvil, 2014): 39-58 ↵