3 The Basic Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS: THE “FINANCIAL STORY”

Financial statements help managers answer a variety of questions:

- Where does this organization’s money come from? Where does it go?

- Is this organization’s mission aligned with its money? Do its revenues and spending reflect is core mission, priorities, and strategy?

- How much of this organization’s spending does it control? How much of its spending is directed by outside stakeholders like donors, clients, or investors?

- How much, if any, does this organization report in “reserves” or “rainy day fund”? Given its operations, what would be the optimal level of reserves?

- Does this organization have enough financial resources to cover its obligations as they come due?

In November 2013 the Contra Costa County (California) Board of Supervisors voted to end nearly $2 million in contracts with the non-profit Mental Health Consumer Concerns (MHCC). The reason: MHCC’s savings account had grown too large.

Since the late 1970s MHCC had offered patient rights advocacy, life skills coaching, anger management classes and several other mental health-related services to some of the poorest residents of the Bay Area. Much of its work was funded by and delivered through contracts with local governments.

In 2007 its Board of Trustees began to divert 10-15% of all money received on government contracts to a reserve account (or rainy day fund). MHCC’s management concluded this policy was necessary after several local governments began to consistently deliver late payments on existing contracts. This new policy was designed to guarantee MHCC would never again be exposed to these types of unpredictable cash flows. MHCC’s Board and management considered this a prudent use of public dollars, and a necessary step to protect the organization’s financial future. From 2007-2011 nearly $400,000 flowed into the new rainy day fund.

Contra Costa County disagreed. They interpreted the contracts to mean that reimbursements were only for actual service delivery expenses. They also pointed out that those contracts prohibited carrying over funds from year to year. A reserve fund containing County funds was therefore a violation of those contracts, and the contracts were terminated. MHCC pointed out that they disclosed the reserve fund strategy in their annual financial reports, and that the reserve allowed them to deliver better, uninterrupted services even during the worst financial moments of the Great Recession. Contra Costa County Supervisor Karen Mitchoff responded by saying MHCC’s financial statements were not the appropriate channel to communicate such a contentious policy choice. She added, “I am not sympathetic to the establishment of the reserve, and the nonprofit board knows they had a fiduciary responsibility to be on top of this.”

The contracts were canceled, and MHCC dissolved in early 2011.

This episode illustrates two of the key take-aways from this chapter. First, an organization’s financial statements are a vital communication tool. They tell us about its mission, priorities, and service delivery strategy. In this particular case, MHCC made a policy decision to deliver less service in the near-term in exchange for the ability to deliver more consistent and predictable services in the future. That choice was reflected several places in MHCC’s financial statements. It’s unrestricted net assets were higher. It’s direct expenses were lower. They also disclosed the rainy day fund policy in the notes to its financial statements. Second, and more important, financial statements are only useful if the audience knows how to read them. In this case, Contra Costa County failed to understand how the rainy day fund policy was communicated in the financial statements, and how that policy affected MHCC’s finances and its ability to accomplish its mission. But without the ability or desire to interpret the financial statements, the County considered MHCC’s actions a breach of contract. Whether a rainy day fund is a direct service expense is an interesting policy question. So is the question of if and how a government should use financial statements for oversight of its non-profit contractors. But to engage these and many other questions, one must first understand how a public organization’s financial statements tell its “financial story.”

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- Identify the fundamental equation of accounting.

- Identify the basic financial statements – balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement – for public organizations.

- Know what information each statement is designed to convey about an organization.

- Contrast the basic financial statements for non-profits to those same statements for governments and for-profit organizations.

- Recognize the key elements of the financial statements – assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses.

Budgeting vs. Accounting

If you want to know how an organization connects its money to its mission, read its budget. If the budget calls for more spending in one program and less in another, that tells us a lot about that organization’s priorities. If one of its programs operates at a loss, but another program’s profits subsidize that loss — that’s also a clear statement about how that organization carries out its mission. We can think of many other ways an organization’s money does or does not connect to its mission. A public organization’s budget lays out the many, unique ways it makes those connections.

But sometimes we want an “apples-to-apples” comparison. Sometimes we want to know if an organization’s mission-money nexus is the same, or different, from similar organizations. Sometimes we want to know how efficiently an organization accomplishes its mission compared to its peers. Sometimes we want to know if an organization is in comparatively good or bad financial health. To answer these types of question you need information found only in financial statements. In this chapter, we walk through the basic financial statements that most public organizations prepare, and the essential concepts from accounting you’ll need to understand the numbers that appear in those statements.

Moreover, we may need to compare an organization’s finances to the finances of other organizations. If our organization’s expenses exceeded its revenues we might consider that to be a failure. Unless, of course, we see that all organizations like it also struggled. If it failed to invest in its capital equipment, we might think it was neglecting its own service delivery capacity, unless we saw other organizations make that same trade-off. These types of comparisons demand financial information that’s based on standardized financial information from a broadly-shared set of assumptions. Budgets are rarely standardized that way.

Fortunately, we can get that information from an organization’s financial statements. Financial statements are the main “output” or “deliverable” from the organization’s accounting function. Accounting is the process of recording, classifying, and summarizing economic events in a process that leads to the preparation of financial statements. Unlike budgets, the numbers reported in financial statements are based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), that prescribe when and how an organization should acknowledge different types of financial activity.

Who Makes Accounting Standards?

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) produces GAAP for publicly-traded companies and for non-profits. The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) produces GAAP for state and local governments. Both the FASB and the GASB are governed by the Financial Accounting Federation (FAF), a non-profit organization headquartered in Norwalk, CT, just outside of New York City. Both Boards are comprised of experts from their respective groups of stakeholders: accounting, auditing, “preparer” (entities that prepare financial statements, like companies and governments), and academia. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the federal government agency that regulates public companies, designates the FASB as the official source of GAAP for public companies. The GASB has not been designated as such, but it is the de facto source of GAAP for governments because key stakeholders like bond investors and the credit ratings agencies have endorsed its standards. GAAP for federal government entities is produced by the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB). The FASAB is comprised of accountants and auditors from federal government agencies. Federal government GAAP is still an emerging set of concepts and practices.

GAAP tells us when an organization can say it “owns” an asset, or when it has “earned” revenue for delivering a service, among many other types of financial activity. These are known as principles of accounting recognition. The key point here is that GAAP is a shared set of “rules of the game” for summarizing and reporting an organization’s financial activities. If an organization offers up GAAP-compliant financial information, we can compare its finances to itself over time, and to other organizations.

Standardized rules aren’t the only difference between budgeting and accounting. Broadly speaking, if budgeting is the story, then accounting is the scorecard. An organization’s budget tells us the activities it wants to do and how it plans to pay for those activities. Politicians and board members love to talk about budgets because budgets are full of aspirations. They’re how leaders translate their dreams for the organization into a compelling story about what might happen.

Financial statements tell us what actually happened. Did the organization the organization’s revenues exceed its expenses? Did it pay for items with cash, or on credit? Did its investments gain value or lose value? How much revenue would it need to collect in the future to pay for capital improvements and equipment? Accountants often see themselves as the enforcers of accountability. That’s why budget-makers and accountants often don’t see eye-to-eye.

These two world views are different in many other important ways. As mentioned, budgeting is prospective (i.e., about the future) where accounting is retrospective (i.e., focused on the past). Budgets are designed primarily for an internal audience – elected officials and board members, department heads and program managers, etc. – where accounting produces financial reports mostly for an external audience of taxpayers, investors, regulators, and funders. Budgeting focuses on the resources that will flow in and out of an organization, also known as the financial resources focus. Accounting focuses on the long-term resources the organization controls and its long-term spending commitments, also known as the economic resources focus. Budgeting is about balance between revenues and spending, where accounting is about balance between an organizations assets and the claims against those assets. These main differences between the two perspectives are summarized in the table below.

| How are Budgeting and Accounting Different? | ||

| Characteristic | Budgeting | Accounting |

| Metaphor | “The Story” | “The Scorecard” |

| Time Frame | Prospective | Retrospective |

| Format | Idiosyncratic/Customized | Standardized |

| Main Audience | Internal | External |

| Focus of Analysis | Inputs/Investments | Solvency/Financial Health |

| Organizing Equation | Planned Revenues = Planned Spending | Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets |

| Measurement Focus | Financial Resources | Economic Resources |

| Cost Measurement | Market Price | Historical Cost |

The Fundamental Equation of Accounting

Everything we do in accounting is organized around the Fundamental Accounting Equation. That equation is:

Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets

An asset is anything of value that the organization owns. There are two types of assets: 1) short-term assets, known more generally as current assets; and 2) long-term assets or non-current assets. A current asset is any asset that the organization will likely sell, use, or convert to cash within a year. Most organizations have supplies or inventory they expect to use to carry out normal operations. Those are the most common current assets.

When someone outside the organization owes the organization money, and the organization expects to collect that money within the year, that’s also a current asset known as a receivable. An organization recognizes an account receivable or A/R when it delivers a service to a client and that client or customer agrees to pay within the current fiscal year. Many non-profits also report donations receivable or pledges receivable. Donations and pledges receivable represent a donor’s commitment to give at a future date. The same logic applies to grants receivable from foundations or governments.

Most public organizations own buildings, vehicles, equipment, and other assets they use to deliver their services. These are long-term assets. They have long useful lives and it’s unlikely the organization would sell these assets, as that would diminish their capacity to deliver services. State and local governments maintain roads, bridges, sewer systems, and other infrastructure assets. These are among the most expensive and important long-term assets in the public sector.

By contrast, a liability is anything the organization owes to others. Or to put it in more positive terms, liabilities are how an organization acquires its assets. Here the short vs. long-term distinction also applies. Short-term liabilities are liabilities that the organization expects to pay within the next fiscal year. The most common are accounts payable for goods or services the organization has received but not yet paid for, and wages payable for employees who have delivered services but not yet been paid.

Long-term liabilities are money the organization will pay at some point beyond the current fiscal year. When an organization borrows money and agrees to pay it back over several years, it recognizes a loan payable or bonds payable. Many public sector employees earn a pension while they work for the government, and they expect to collect that pension once they retire. If the government has not yet set aside enough money to cover those future pension payments, it must report a pension liability.

What’s left is called net assets. Technically speaking, net assets are simply the difference between assets and liabilities. For private sector entities, this difference is known as owner’s equity.

Owners = Equity Holders

In for-profit organizations the fundamental equation is Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity. Conceptually, a for-profit company’s owners have a claim to all its assets that do not have an offsetting liability. Or put differently, the company’s owners have a claim to all of its assets not otherwise promised to creditors or suppliers. When you buy stock (or “shares”) of a for-profit company you are, in effect, buying a portion of that company’s owner’s equity. That’s why stocks are also known as equities. If a company’s assets grow faster than its liabilities, its equity will become more valuable, the price of its stock will increase, and investors who hold that stock will make money. For instance, some extraordinarily fortunate investors purchased Facebook’s original stock at around $5/share. Today Facebook stock sells for around $120/share. As the Facebook’s user base and annual revenues have grown, its assets have grown much faster than its liabilities, and its stock price has steadily increased.

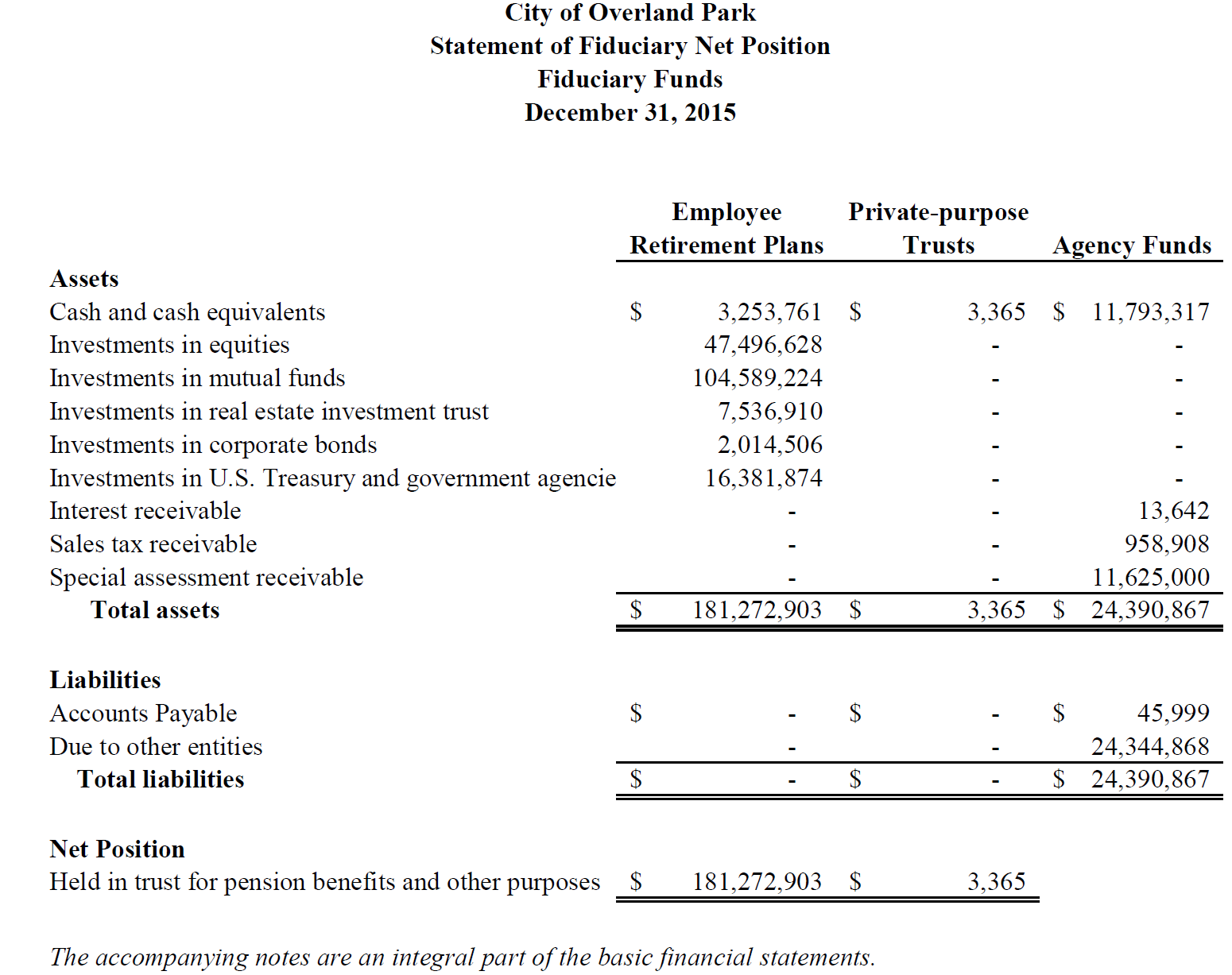

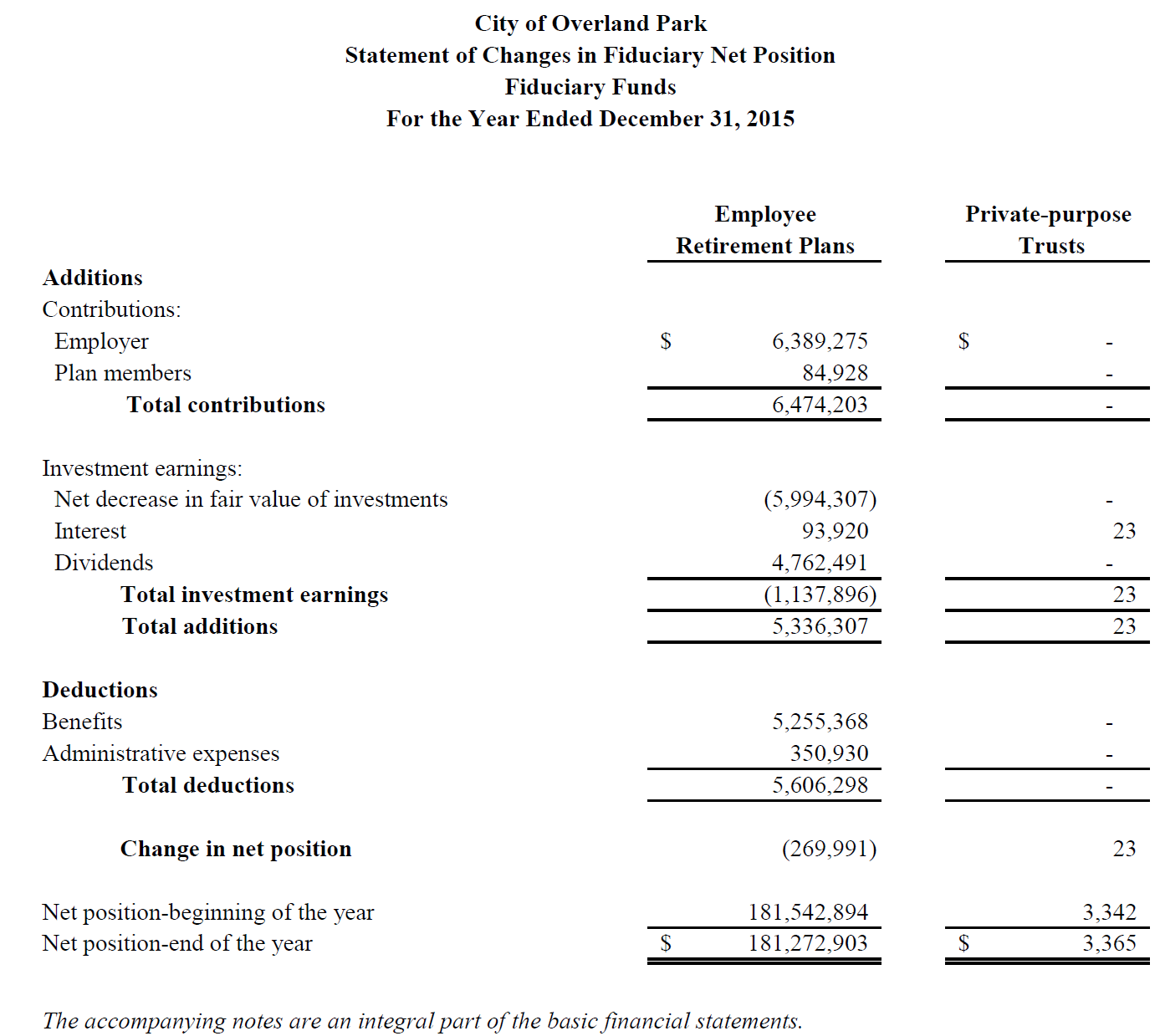

Public organizations don’t have “owners.” Instead, they have stakeholders, or anyone who has an interest, financial or otherwise, in how well the organization achieves its mission. For governments, taxpayers are a rough analog to owners. But unlike investors in a for-profit company, taxpayers don’t have a legal claim to the government’s assets. Taxpayers’ main interest is that the government delivers the services they expect it to deliver. Donors and funders who give money to a non-profit organization care about its financial health, but they also don’t expect to get their money back if the organization fails. Mostly, they care that the organization will continue to serve its clients and the community at large. For these reasons, net assets are an important part of a government and non-profit finances, but they don’t have quite the same meaning as owners’ equity for a for-profit entity.

That said, we can think of net assets as an indicator of the organization’s financial strength or financial health. If its net assets are growing, that suggests its assets are growing faster than its liabilities, and in turn, so is its capacity to deliver services. If its net assets are shrinking, its service-delivery capacity is also shrinking.

We also have to think about the restrictions on net assets. Net assets are reported as either unrestricted net assets, temporarily restricted net assets or permanently restricted net assets. Unrestricted net assets have no donor-imposed stipulations but may include internal or board-designated restrictions. Temporarily restricted net assets represent assets with time and/or purpose restrictions stipulated by a donor. Permanently restricted net asset represent assets with donor restrictions that do not expire.[1] We are therefore interested in whether the growth in an organization’s capacity is limited to donor-funded programs (i.e., temporarily or permanently net assets) or whether the growth is in its unrestricted position.

The Basic Financial Statements

All organizations that follow GAAP, both public and private, produce three basic financial statements:

- Balance Sheet. Presents the organization’s assets, liabilities, and net assets at a particular point in time.

- Income Statement. Presents the organization’s revenues, expenses, and changes in net assets throughout a particular time period.

- Cash Flow Statement. Shows how the organization receives and uses cash to carry out its mission.

In the discussion that follows you’ll see more detail about each statement and how the information it contains can inform key management and policy decisions.

When considering an organization’s financial statements keep one central point in mind: Net assets are the focal point. Changes in assets, liabilities, revenues, expenses, and cash flows will affect net assets differently. Each of the three financial statements illuminates different dimensions of those changes. Regardless of the organization’s structure or mission, its financial statements are organized around changes in net assets.

Also, each statement’s presentation style and terminology can vary depending on the type of organization that prepared it. This table summarizes those differences.

Many of the differences in labeling are intended to contrast the mission orientation of non-profits and governments with the profit orientation of for-profits. We see this most clearly in the income statement. For-profit organizations often call the income statement the “profit/loss statement,” given its purpose is to distinguish its profitable products and services from its non-profitable products and services. For governments and non-profits, the focus is on “activities.” The question here is not whether the organization’s activities are profitable, but rather how to do those activities advance its mission. In the aggregate, they must take in more revenue than they spend, or they will cease operating. But “profitability” is not their main goal.

| Statement | What For-Profits Call It | What Non-Profits Call it | What Governments Call It | ||

| Government-Wide Statements | Governmental Fund Financial Statements | Proprietary Fund Financial Statements | |||

| Balance Sheet | Balance Sheet; Statement of Financial Position | Statement of Financial Position | Statement of Net Position | Balance Sheet | Balance Sheet |

| Income Statement | Income Statement; Profit & Loss Statement; “P&L”; Operating Statement | Statement of Activities | Statement of Activities | Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances | Operating Statement |

| Cash Flow Statement | Cash Flow Statement; Statement of Cash Flows | Statement of Cash Flows | N/A | N/A | Cash Flow Statement |

You’ll also note several differences in what governments call these statements. We’ve talked already about how financial statements illuminate operational accountability, or how efficiently and effectively an organization used its financial resources to advance its mission. Taxpayers want to know their government delivered services efficiently and effectively. To that end, state and local governments prepare a set of “government-wide” financial statements. These statements present the government’s overall financial position, and they offer some insight into its ability to continue to deliver services in the future. These government-wide statements are, with a few modifications, conceptually similar to the basic financial statements for a non-profit or for-profit.

The government-wide balance sheet is called the Statement of Net Position, and the government-wide income statement is called the Statement of Activities. By calling the income statement, the Statement of Activities, the governmental accounting standards-setters have sent a clear message: governments exist not to generate income, but to produce activities. This also explains why there’s no government-wide cash flow statement. Information about how a government generates and uses cash does not necessarily help us understand if it is achieving its mission.

But with governments, operational accountability is only part of the story. Taxpayers also want to know their government did what they told it to do. They want to know if it delivered the services they wanted with the revenues they gave it. That’s fiscal accountability.

When we think of fiscal accountability in government we usually think of the budget. A government’s budget is not just a plan; It’s the law. Most governments’ constitutions or charters require them to lay out their planned revenues and spending in a special law called an appropriations ordinance. They must literally pass a law that makes their budget intentions clear. If they spend more than their budget allows or spend money in ways not specified in their budget ordinance, they are breaking the law.

Budgets are enshrined in law because they are one of our most effective tools to ensure inter-period equity. Inter-period equity is the idea that if a government follows its budget, it is living within its means and it is less likely to pass costs onto future generations.

Fiscal accountability and inter-period equity are so important that they’re built not just into a government’s budget, but also into its financial statements. For instance, imagine that a school district levies a special sales tax to pay for school buildings. Taxpayers want to see how much revenue that tax generated, how much money the school district borrowed to build those buildings, how much of that revenue has been used to repay that borrowed money, and so on. They’ll want fiscal accountability on that special tax.

For taxpayers to assess this they’ll need to see those revenues, expenditures, assets, and liabilities presented separately from all other operations. To do that, the school district will present those finances in a stand-alone special revenue fund.

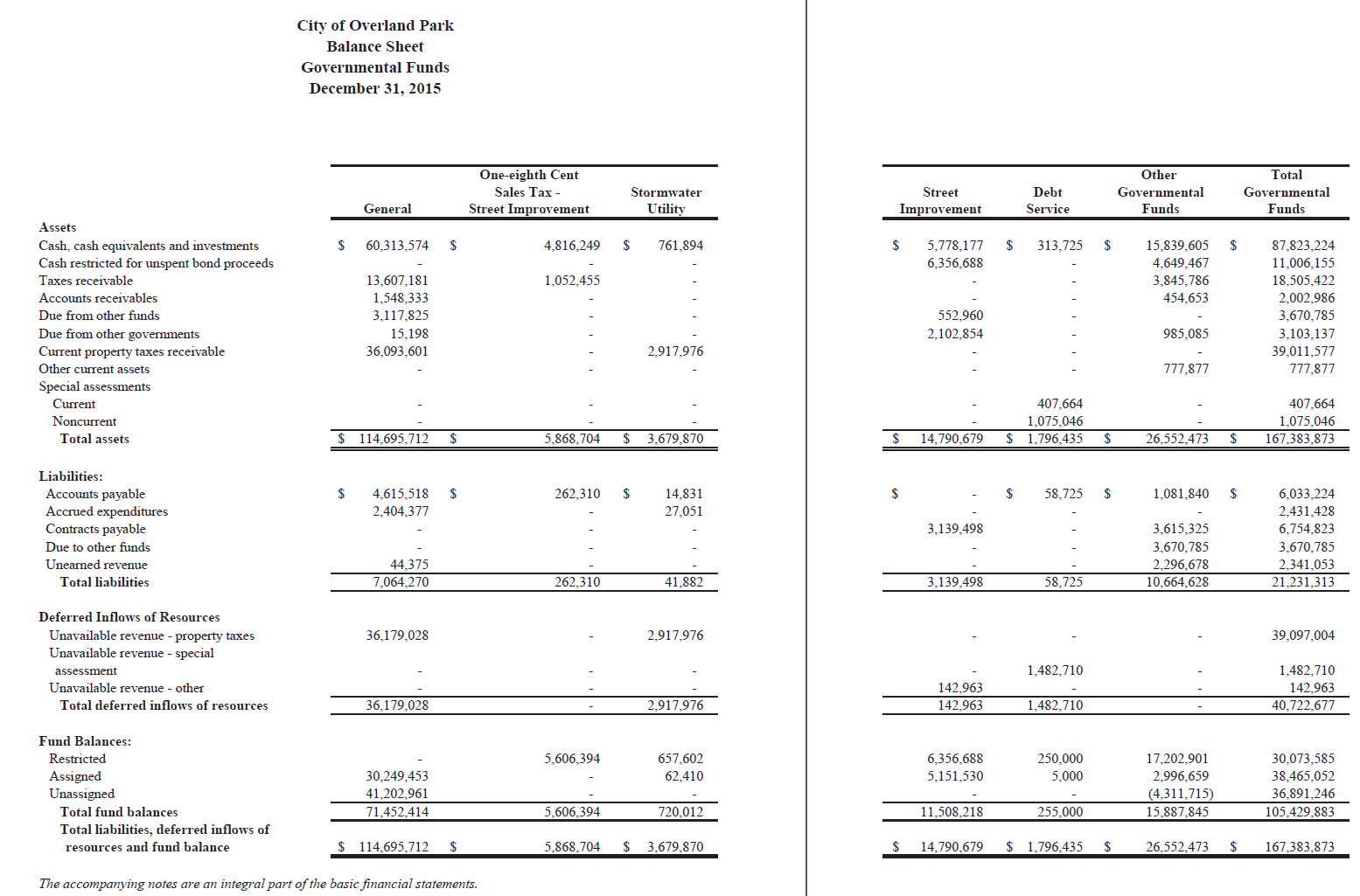

A fund is a stand-alone, self-balancing set of accounts with a specific purpose. A government’s general fund is where it accounts for its general services that are paid for through general revenue sources. It’s where local governments account for police, fire, public health, and other services paid for through property taxes and general sales taxes. It’s also where state governments account for their Medicaid programs, state parks, state patrol, and other general services paid for through state income taxes and statewide general sales taxes. For most governments the general fund is the largest and most carefully-watched. According to GAAP, a government’s general fund, special revenue funds, and capital projects funds are collectively called its governmental funds. You can think of the governmental funds as a government’s core services and operations.

Like the budget, governmental funds are focused on near-term revenues and spending. For that reason the information you see in funds is prepared using a different set of accounting principles. Those principles are known as modified accrual accounting (or “fund accounting”) and are described later in this chapter.

Since funds are self-balancing, we rewrite the fundamental equation for the modified accrual context as:

Assets = Liabilities + Fund Balance

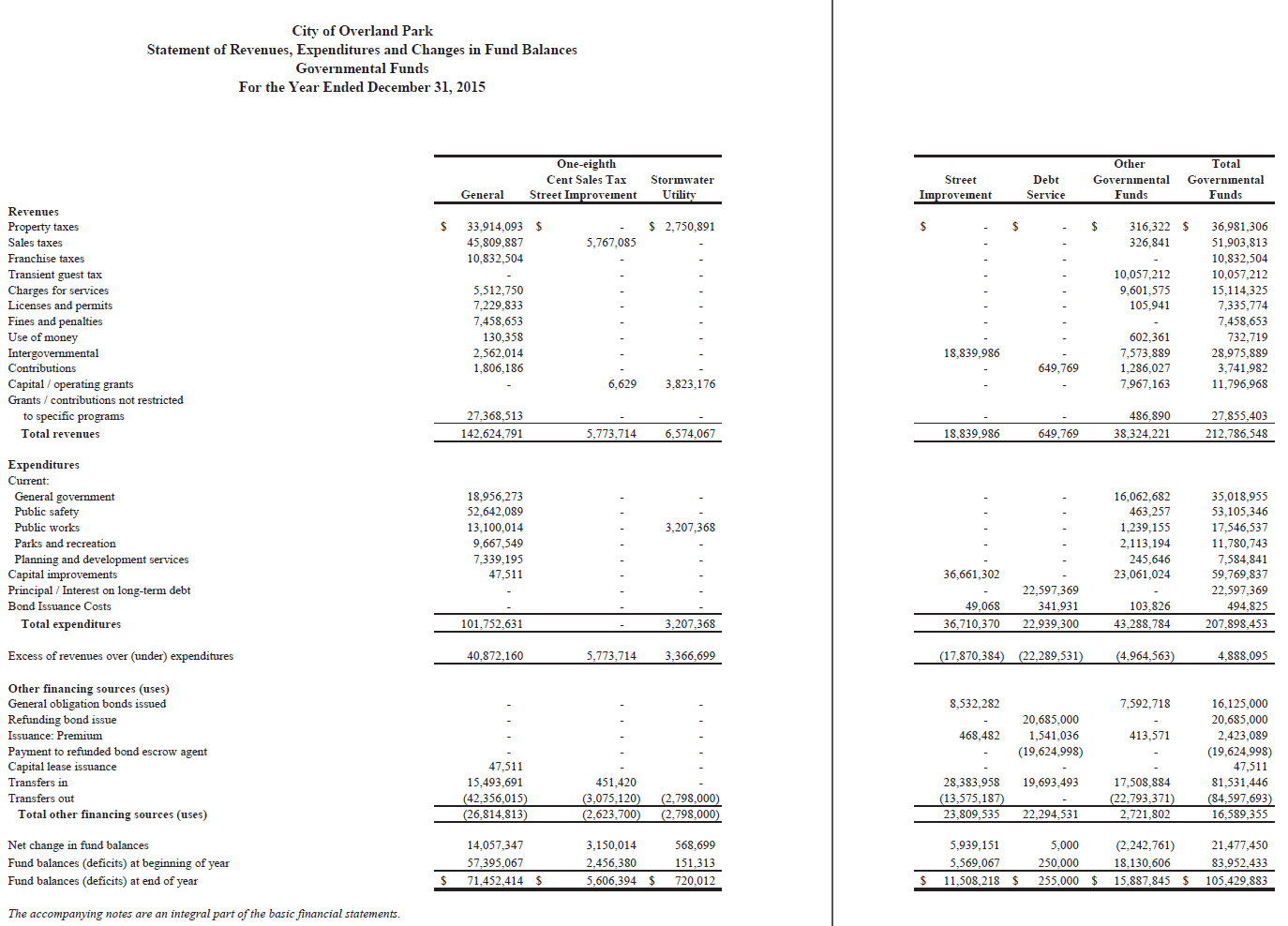

Funds are so important to governments that they are required to present a separate set of fund financial statements, prepared on the modified accrual basis of accounting. The balance sheet in the governmental funds is simply called the balance sheet, and the income statement is called the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balance. Like with the government-wide statements, there is no cash flow statement for the governmental funds.

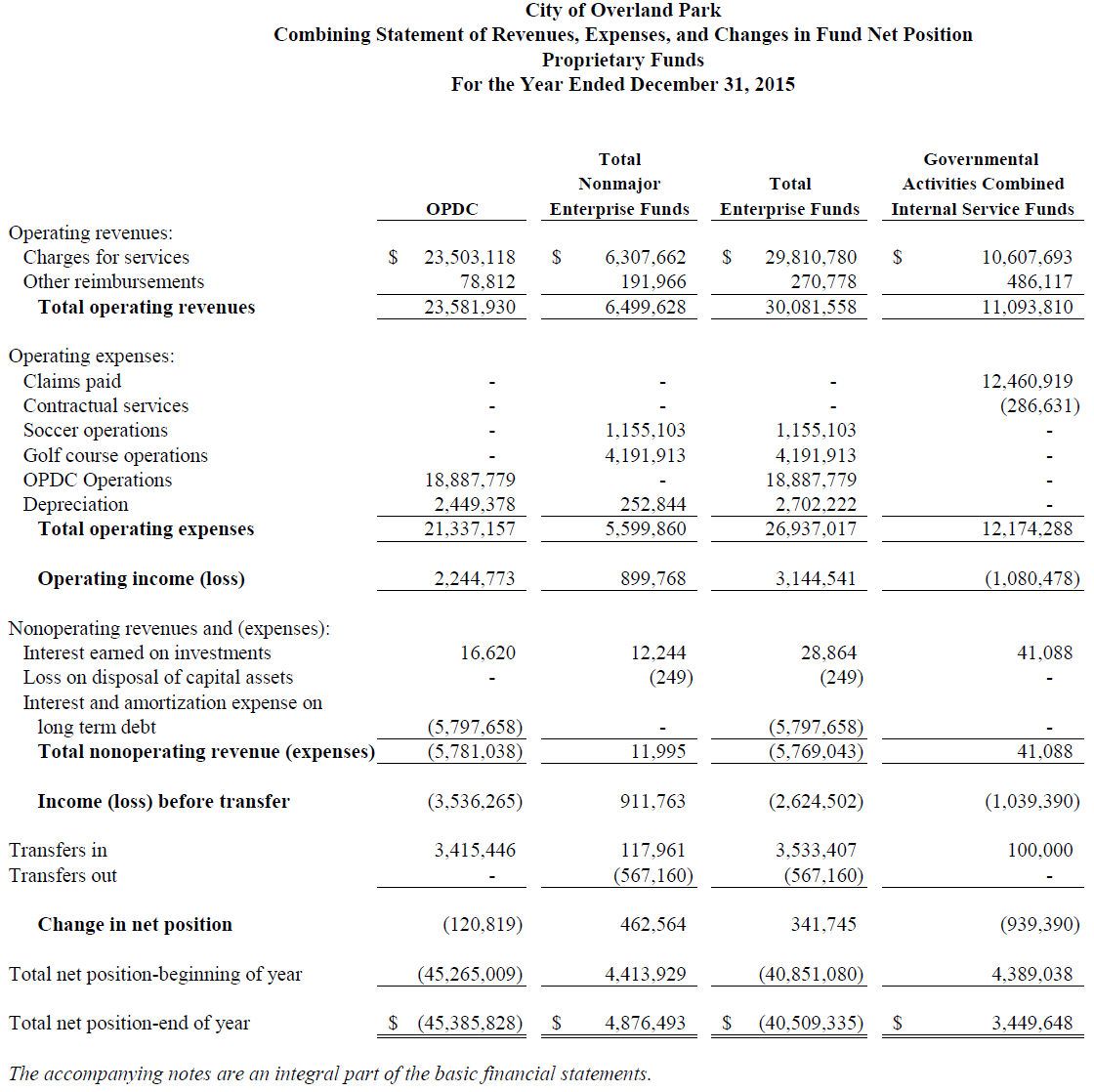

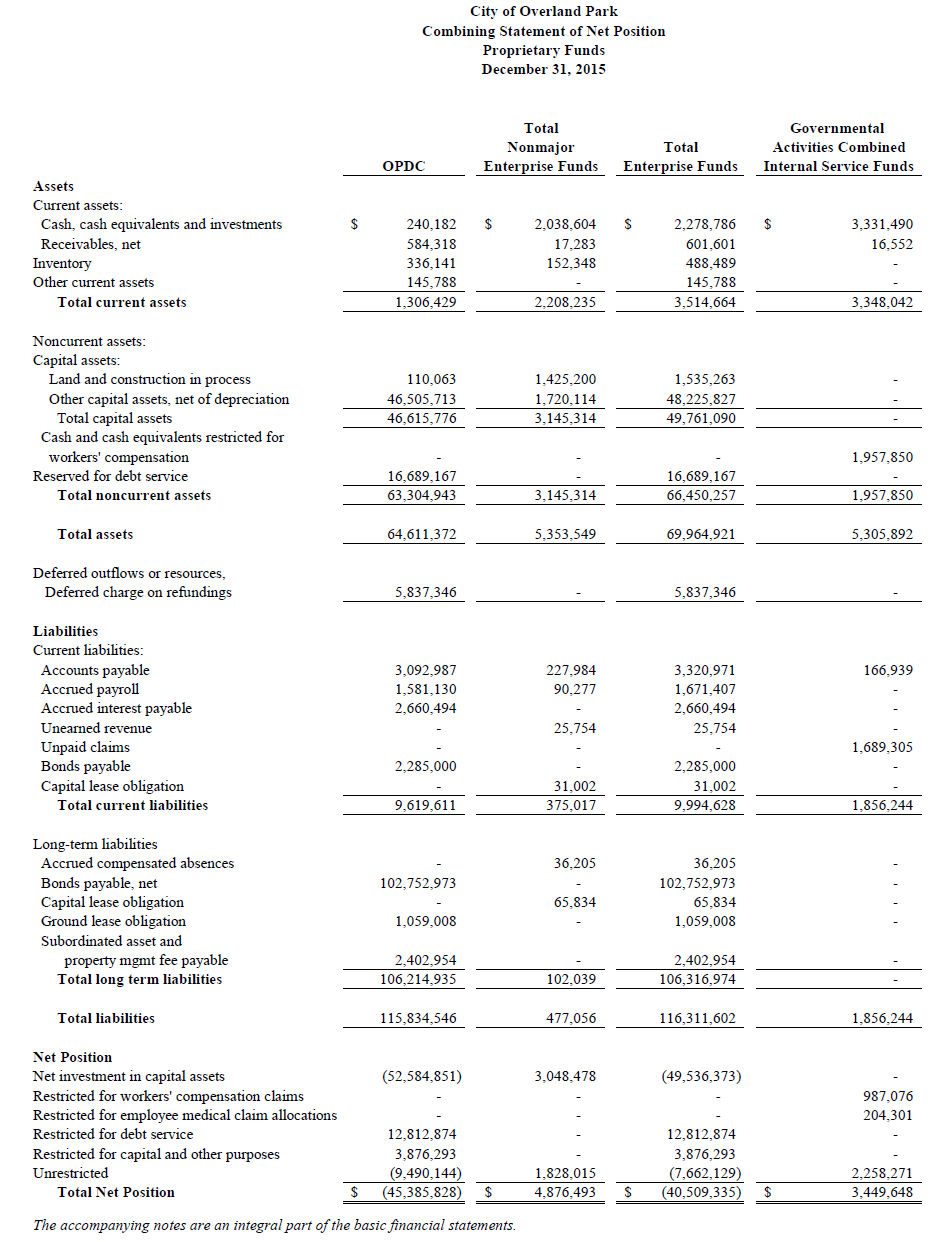

Governments also deliver goods and services whose operations are quite similar to what we’d find in the private sector. Examples include water utilities, golf courses, swimming pools, waste disposal facilities, and many others. These are known as business-type activities or proprietary activities. In concept, business-type activities should cover their expenses with the revenue they generate through fees and charges for their services. In fact, many governments operate business-type activities because those activities are profitable and can subsidize other services that cannot pay for themselves. Since business-type activities are expected to pay for themselves, we account for them on the accrual basis and prepare a separate set of proprietary fund financial statements. Accrual basis accounting, assumes an organization records a transaction when that transaction has an economic impact, regardless of whether it spends or receives cash. Those statements follow the traditional titles of balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement.

What is the Audit Report?

At the beginning of every set of financial statements, you’ll find an audit report. This report is formatted as a letter, prepared by an external financial auditor, presented to the organization’s board and management and incorporated in the audited financial statements. That auditor reviews the organization’s statements, tests its procedures and systems to prevent fraud and abuse (also known as internal controls), interviews its staff, examines a selected group of specific transactions, and performs other work designed answer a simple question: Are the organization’s financial statements a fair presentation of its actual financial position? Usually, the audit report expresses an unqualified opinion, meaning the auditor believes the financial statements are a fair presentation of the organization’s financial position. An unqualified audit report will contain language to the effect of “…these financial statements present, fairly, and in all material respects, this organization’s financial position.” If the auditor has reason to believe the financial statements do not present that position fairly they will issue a qualified opinion, or, in rare cases, an adverse opinion.

The Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is designed to answer a simple question: What is this organization’s current financial position? Financial position has both a short-term and a long-term component. If current assets exceed current liabilities, then the organization is in a good short-term financial position. If long-term (i.e. non-current) assets exceed long-term liabilities, the organization is in a good long-term financial position.

For that reason, a point of emphasis for the balance sheet is the relationship between the organization’s assets and liabilities. If assets grow faster than liabilities, net assets will increase. And vice versa. Later we’ll cover some more precise measures, also known as financial statement ratios, you can use to answer these questions.

The balance sheet offers a lot this sort of detail on why net assets do or do not increase. To that point, when looking at an organization’s balance sheet you should ask a few questions:

- Do its total assets exceed its total liabilities? If they do, that’s a good indicator of a good long-term financial position.

- Do its current assets exceed its current liabilities? If they do, that’s a good indicator of a strong short-term financial position.

- What portion of its current assets are reported under cash? Does it appear to have a lot of cash relative to its other assets and liabilities? Cash is critical. At the same time, it’s possible for an organization to have too much cash. If it has more cash than it needs to cover its day-to-day operations, then it could invest some of that idle cash in marketable securities or other safe investments, and earn a small investment return.

- What portion of its assets are reported as receivables? What proportion of receivables are due in 12 months or less? What proportion of receivables due are from a single donor or grantor? This can be a source of financial uncertainty or even weakness, depending on the donors or payees in question.

- What is the relationship between its current and non-current assets? How much does the organization report in buildings and equipment? The organization will likely need to use cash, and other short-term assets, to pay for and maintain its long-term assets.

- What portion of net assets are unrestricted? Are temporarily restricted? Are permanently restricted? Unrestricted and temporarily restricted net assets can be use to cover short-term spending needs, if they are used within the confines of the donor restrictions.

- Does the organization have non-current liabilities? How might these affect the organization’s current assets in the future? Long-term liabilities like loans, bonds, legal settlements, and pensions increase demand for current assets like cash.

It’s important to keep in mind that the balance sheet is a snapshot in time. When an organization’s accounting staff prepare a balance sheet they simply report the balances in each of organization’s main financial accounts on a particular day. Usually, that day is the last day of the fiscal year. Keep in mind that if an organization has a dynamic balance sheet – i.e., it has a lot of receivables or payables, or it has a lot of investments whose value fluctuate – then its total assets and total liabilities can look quite different from one week to the next or from one month to the next.

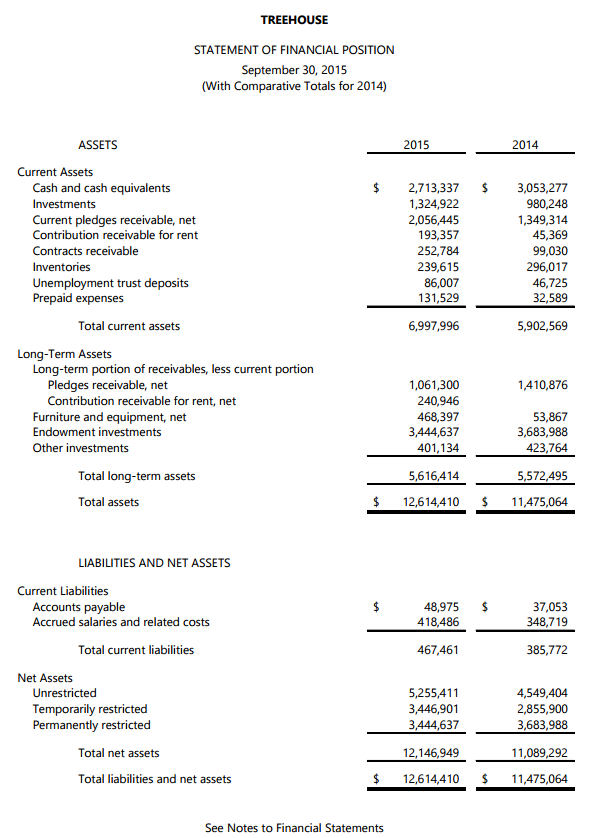

Let’s look at an example. Here you’ll see Fiscal Year 2015 Balance Sheet – i.e. the Statement of Financial Position – for a non-profit organization called Treehouse. Treehouse supports children in foster care with tutoring and other educational support (e.g., counseling, food, clothing). It was founded in 1988, and serves nearly 8,000 children in greater Seattle, WA.

The balance sheet is organized in order of liquidity. The most liquid assets appear first, and the least liquid assets appear near the bottom. Liquidity refers to how quickly an asset can be converted to cash with minimal loss in value. We can convert an asset to cash by selling it, or, in the case of receivables, by collecting on it. Cash is, of course, the most liquid asset. That’s why it’s listed first. Cash equivalents (e.g., commercial paper, and marketable securities like money market mutual funds and overnight re-purchase agreements or “Repos”) are extremely safe investments that can be converted to cash immediately at low or no cost.

Book Value vs. Market Value

Accountants usually report assets at historical cost, or the cost the organization paid to acquire them. Historical cost is also called “book value” because it’s the value at which the accountant recorded that asset in the organization’s “books.” For instance, if an organization purchased a building for $500,000 ten years ago it will report a book value of $500,000 on its balance sheet. Meanwhile, an appraiser might estimate that a buyer would be willing to pay $1,000,000 for that building today. This is an estimate of the building’s market value. Accountants prefer historical cost. In fact, that preference is so strong it’s called the historical cost rule of accounting. Until that building is actually bought or sold for $1,000,000, that figure is just a guess that’s too unreliable as a basis for financial reporting.

Treehouse reports the most typical current assets:

- Investments (current assets). Investments includes holdings of stocks, bonds, and other typical financial instruments. By definition, investments reported as current assets are bought and sold less frequently and less liquid than marketable securities.

- Receivables. When someone pays money they owe to the organization that money, that receivable is converted to cash. Treehouse reports receivables for pledges, rent (it owns property that it rents to others), and contracts. Also note that it reports net receivables. This means it has subtracted from that receivables figure, the portion of those receivables it has determined it cannot collect. Those removals are known as bad debt expense, and are described later in this chapter.

- Inventory. This includes goods that the organization intends to sell or give away as part of delivering its services. Much of Treehouse’s inventory is held in its “Wearhouse,” a thrift store where children can pick up clothing and personal items for free. Many organizations (Treehouse not included) report a separate category for supplies. These are goods and materials, usually commodities, that the organization intends to use while delivering its services. Unlike marketable securities and investments, there may not be a robust market for supplies and inventory, so they are among the least liquid current assets.

- Pre-paid Expenses. When an organization pays in advance for services it will use later – such as insurance, memberships, subscriptions, etc. – that’s known as a pre-paid expense. If the organization can cancel, renegotiate, or otherwise change a pre-paid and get cash back in return, then the pre-paid can be converted to cash. This is rare.

Treehouse also reports the most common long-term assets. These are also listed in order of liquidity:

- Long-term Receivables. Some receivables are received over multiple fiscal periods. This is especially true for long-term grants and contracts, and for donors who choose to give at regular intervals over several years. These long-term receivables are also reported net of bad debt.

- Furniture and Equipment. Reported at historical cost (see below) and net of depreciation (see later in this chapter). These are also known as capital assets or property, plant, and equipment (PPE). They are illiquid as there may or may not be an interested buyer. If Treehouse owned a building the value of that building would also be reported here.

- Endowment Investments represent donated funds with a explicit restriction that funds not be expended, but rather, invested for the purpose of producing income. This is the precise reason why these investments are reported as long-term assets. Its not because the owner cannot sell — or that they cannot be sold, but rather if they are sold, they must be replaced by an equivalent financial instrument. Earnings from endowment investments can be used to advance the organization mission as long as the organization exists. Treehouse maintains a sizeable pool of endowment investments. For some organizations, endowment investments may not be explicitly reported in the balance sheet, but these are often disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

- Other Investments. Many investments are not liquid because their owner is not allowed to sell them. This is usually true of holdings in hedge funds, private equity, and other investment vehicles where investors give up liquidity, but expect a more profitable investment in return. Some investments are less liquid because there are simply fewer potential buyers. Commercial real estate, for instance, can take some time to sell because there are simply fewer potential investors interested in those types of properties compared to, say, residential real estate. All these investments are reported as “other” long term assets.

Fair Value vs. Historical Cost

Investments are an important exception to the historical cost rule. Most investments trade on an exchange like the New York Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. The prices quoted on those exchanges are a good estimate of the price at which that organization could sell that asset. In this case, an accountant would replace historical cost with a fair value estimate based on the price from an exchange. So for instance, say a non-profit bought 1,000 shares of stock for $50,000 three years ago at historical cost is $50/share. If on the last day of the current fiscal year, that stock was trading for $75/share, the accountant would record that stock on the balance sheet at a mark-to-market fair value estimate of $75,000. Accountants are comfortable relaxing the historical cost rule for investments because for most investments, we can quickly and easily observe an accurate market price.

Liabilities are also listed in reducing order of liquidity. Liquidity of a liability refers to how quickly the organization will need to pay it. Treehouse’s balance sheet includes the two most common current liabilities – accounts payable and accrued salaries and related costs (i.e. wages payable). These are liabilities that will come due within the fiscal year. Like many non-profits, Treehouse does not report any long-term liabilities. If it had a mortgage, loan payable, or other liabilities that will come due over multiple years it would report them as long-term liabilities.

At a glance, three key features of Treehouse’s balance sheet stand out. First, its current assets far exceed its current liabilities. This indicates a strong near-term financial position. Treehouse has more than enough liquid resources on hand to cover liabilities that will come due soon. However, roughly one-third of those current assets are pledges receivable. This introduces some uncertainty into Treehouse’s overall asset liquidity. What’s more, a substantial proportion of Treehouse’s net assets are reported as either temporarily restricted or permanently restricted. This indicates that a good amount of Treehouse’s overall spending is for donor-directed programs. Taken together, the findings suggest Treehouse is in a strong financial position, has good balance across its current and long-term assets, and does not have long-term liabilities. At the same time, it does not have full autonomy over its financial resources.

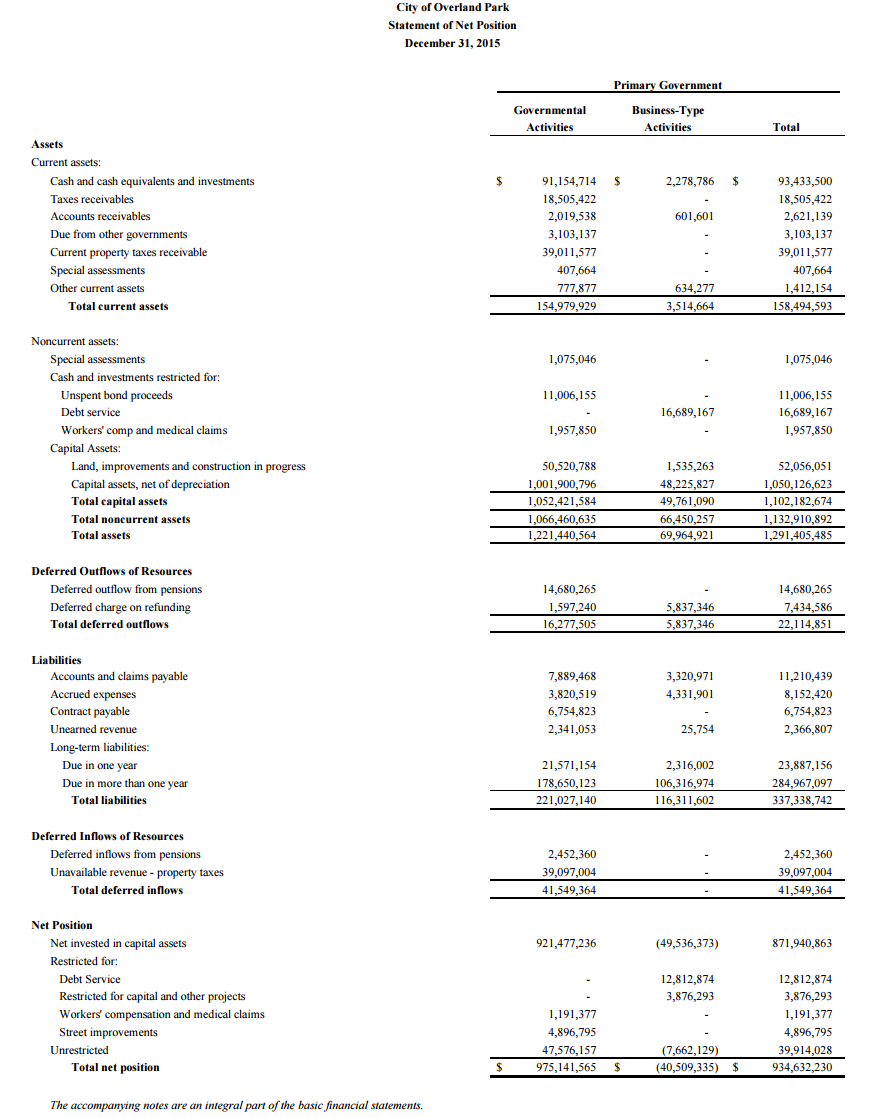

For Governments – The Statement of Net Position

Governments prepare government-wide financial statements that are similar to the basic financial statements for a non-profit or for-profit entity. These government-wide statements answer some of the key questions taxpayers ask about their government:

- Has its overall financial position improved or deteriorated?

- How much has it invested in its infrastructure and other capital assets?

- Were its current year revenues sufficient to pay cover full cost of current year services?

- How much does it depend on user fees and other exchange-like revenues compared to general tax revenues?

- How does its financial position compare to other, similar governments?

To illustrate, let’s look at the financial statements for the City of Overland Park, KS. Overland Park (OP) is a large suburban community just west of Kansas City, MO. In 2015 its population was just under 175,000.

Let’s start with OP’s government-wide balance sheet, known formally as the Statement of Net Position. It shows OP’s balances for its assets, liabilities, and other accounts on the final day of its fiscal year, December 31. This statement includes separate presentations for governmental activities and business-type activities. Governmental activities are supported by taxes and other non-exchange revenues. Business-type activities, or proprietary activities, are supported by exchange-like revenues, or fees the government charges for goods and services it delivers. For local governments, government-owned utilities, recreational facilities, golf courses, and other enterprises are almost always considered business-type activities. For state governments, business-type activities usually include programs like workers compensation/unemployment funds, state lotteries, university tuition assistance programs, private corrections facilities, and many other activities.

On the asset side, we see many of the same assets we saw at Treehouse. OP has cash, investments, and accounts receivable. Like a non-profit, current assets are assets it expects to collect within the fiscal year. The same applies to the liabilities side. OP has accounts payable, unearned revenue, accrued expenses, and other items we’d see at a non-profit or for-profit entity. But there are several important differences. First, note the two new categories of deferrals. A government records a deferred inflow of resources when it receives resources as part of a non-exchange transaction in advance. Pre-paid property taxes are a good example. Imagine a property owner in OP paid their property taxes for 2016 in July of 2015. OP might be tempted to call this deferred revenue because it received payment in advance for services it will deliver next year. However, that would be incorrect because property taxes are a non-exchange revenue. Taxpayers in OP don’t pay property taxes for specific services at specific times; they pay for a variety of services delivered at various times throughout the year. There’s no real exchange. So in this case, OP would recognize the taxpayer’s cash as an asset, but simultaneously recognize a deferred inflow of resources. Next year, when OP delivers the police, fire, and other services funded by those property taxes, it will reduce cash and reduce that deferred inflow.

But there are several important differences. First, note the two new categories of deferrals. A government records a deferred inflow of resources when it receives resources as part of a non-exchange transaction in advance. Pre-paid property taxes are a good example. Imagine a property owner in OP paid their property taxes for 2016 in July of 2015. OP might be tempted to call this deferred revenue because it received payment in advance for services it will deliver next year. However, that would be incorrect because property taxes are a non-exchange revenue. Taxpayers in OP don’t pay property taxes for specific services at specific times; they pay for a variety of services delivered at various times throughout the year. There’s no real exchange. So in this case, OP would recognize the taxpayer’s cash as an asset, but simultaneously recognize a deferred inflow of resources. Next year, when OP delivers the police, fire, and other services funded by those property taxes, it will reduce cash and reduce that deferred inflow.

The inverse is true for deferred outflows. Say, for example, that most of OP’s employees belong to the Kansas Public Employees’ Retirement System. That System sends OP a bill for $14.86 million to cover pensions and other costs related to the OP employees now in the System. That bill is due on January 20, 2016. In December 2015 OP closes its books and prepares its financial statements, but its City Council signs papers acknowledging their commitment to make that $14.86 million shortly after the start of the coming fiscal year. Those resources are effectively unavailable for the coming year.

OP might be tempted to call this accounts payable because it has owes money for a service it’s already received. But that’s not entirely true. A state retirement system is not a service, and even if it was, it wouldn’t deliver that service until the next fiscal year. So instead, OP will book this as a deferred outflow of resources, and book a corresponding increase in liabilities. By not booking a liability, and not actually spending the cash, OP’s FY15 balance sheet looks much stronger. At the same time, it has committed resources to the future, and that will impact its operations in the coming year. By recognizing a deferred outflow of resources, OP has offered us a clearer picture of how well the resources it collects each year cover its annual spending needs.

That’s How We Roll

Most governments have dozens, if not hundreds, of individual funds. It’s not feasible to report on all of them. So to simplify the reporting process governments draw a distinction between major funds and non-major funds. Different governments define “major” differently, but most use a benchmark of 5-10%. That is, a fund is major if it comprises at least 5-10% of the total revenues of all government activities or all business-type activities. GAAP requires a set of financial statements for each major fund. The remaining non-major funds are “rolled up” into a single set of financial statements.

Critics of government financial reporting often say that governments have too many funds. When a government’s finances are spread across so many different reporting units it’s difficult, if not impossible, to develop a clear picture of its financial position. Supporters of the status quo say that funds, while cumbersome, are our best available means to ensure fiscal accountability.

With the addition of deferrals, we re-write the fundamental equation for the government-wide financial statements as:

Assets + Deferred Outflows = Liabilities + Deferred Inflows + Net Position

In the traditional fundamental equation, we use “net assets” to identify assets minus liabilities. When we add deferrals, the “net assets” label no longer captures everything on the right side of the equation, but “net position” does.

Going back to OP’s assets, we see items that we’d only see on a government’s financial statements.

- Taxes Receivable. Taxes, usually property taxes, that OP is owed for 2015 and expects to receive early in 2015.

- Special Assessments. Recall special assessments are taxes, usually property taxes, levied on specific parcels of property or groups of properties. Special assessments are reported separately from general property taxes because they are used to fund specific assets like sidewalks and street lighting, and specific services like economic development.

- Due from Other Governments. Local governments routinely partner with other local governments. These inter-local agreements or cross-jurisdictional sharing arrangements are common in areas like emergency management, police and fire response, and public health, among many other service areas. If those agreements require one government to pay another government, those payments appear as “due to other governments.”

Like with most governments, the majority of OP’s liabilities are long-term liabilities. State and local governments finance most of their infrastructure improvements with long-term bonds (either general obligation bonds or revenue bonds), usually paid off over a 20 up to 30 year period. When a government issues bonds it recognizes a long-term liability, and the borrowed cash as an asset. Cities, counties, and school districts rarely go bankrupt or cease operations, so investors are willing to invest in them for such long periods of time. This is quite different from non-profits or for-profits, where the going concern question is not always so clear.

Net position and its components are also a uniquely governmental reporting feature. Here OP is similar to other states and local governments.

- Net Investment in Capital Assets is the value of OP’s infrastructure assets (net of depreciation) minus the money it owes on the bonds that financed those assets. All capital assets are reported in this component of net assets, even if there are legal or other restriction on how the government is to use them for service delivery.

- Governments restrict portions of their net position for many purposes. Restricted net position is virtually the same as restricted net assets for a non-profit. According to governmental GAAP, a portion of net position is restricted if: 1) an external body, like bondholders or the state legislature, can enforce that restriction, or 2) the governing body passes a law or other action that imposes that restriction. For most state and local governments, the largest and most important portion of restricted net position is restricted for debt service. In 2001 OP created a non-profit organization called the Overland Park Development Corporation (OPDC). OP includes OPDC in its financial statements as a component unit (see below). Shortly after its creation OPDC financed, constructed, and now owns a Sheraton Hotel that’s designed to bolster local convention business. OP agreed to levy a small tax on hotel rooms and car rentals within the city – a “transient guest tax” – to pay the debt service on the bonds OPDC used to finance that hotel. Almost all of OP’s restricted net position is related to that debt service and to capital spending required to maintain the hotel.

- A government’s unrestricted net position is akin to a non-profit’s unrestricted net assets. These are net assets available for spending in the coming fiscal year.

What’s a Street “Worth”?

When we look at Net Investment in Capital Assets we’re forced to ask, what’s the “book value” of a capital asset. Recall that most organizations, public and private, record their tangible capital assets at historical cost. That means they record a new asset at whatever it cost to construct or purchase it, and then depreciate it over it’s useful life. Most of the assets non-profits carry on their books – buildings, vehicles, office furniture, etc. – have useful lives of 10-30 years. But how does a government determine the book value of a street? Or a school building? Or a sewer system? Many of these assets were built long before governments started preparing modern financial statements, and many of them have useful lives of more than 100 years.

States and localities dealt with precisely this issue when they implemented Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement 34. This statement – euphemistically known as “GASB 34” – required governments, for the first time, report the book value of their capital assets. Prior to GASB 34, they reported what they spent each year on capital assets as an expense, but they did not include their full book value. In other words, they did not capitalize their infrastructure assets.

Fortunately, many governments were able to reconstruct historical cost figures by reviewing old invoices, purchase orders, construction plans, and other historical documents. Public works staff at states and local governments around the country spent thousands of hours researching old records to determine what they spent to build their original streets, bridges, sewer systems, university buildings, and other key pieces of infrastructure. Those assets were then grouped into fixed asset networks, assigned a useful life and a depreciation schedule, and depreciated to the present day. That depreciated figure became the original capitalized infrastructure asset value.

So for most governments the figure Net Investment in Capital Assets is the original capitalized value depreciated to a present day, plus any investments since implementing GASB 34. A few governments take a different approach allowed under GASB 34 known as the modified method. Here a government capitalizes its infrastructure assets, but instead of depreciation, it estimates how much it will need to spend each year to maintain those assets in good working condition. If it can demonstrate that it’s making those investments, it need not depreciate, and the book value does not change.

Why take the time and effort to do this? Because investors and taxpayers want to know if their government is taking care of its vital infrastructure. If the Net Investment in Capital Assets is stable or increasing, it suggests a government is making precisely those investments.

The Income Statement

The Income Statement is designed to tell us if an organization’s programs and services cover their costs? In other words, is this organization profitable?

It’s organized by revenues and expenses. In GAAP, revenue is defined as what an organization earns for delivering services or selling goods. Expenses are the are the cost of doing business. Whenever possible, think of expenses in terms of the revenues they help to generate. For non-profit organizations this relationship is sometimes clear, and sometimes not. For example, imagine that a non-profit conservation organization operates guided backpacking trips. Participants pay a small fee to participate in those trips. To run those trips the organization will incur expenses like wages paid to the trip guides, supplies, state permitting fees, and so forth. These are expenses incurred in the course of producing backpacking tour revenue. Here that relationship between revenues and expenses is clear.

This same organization might sell coffee mugs, water bottles, and other merchandise, and then use those revenues to support it’s conservation mission. The expenses to produce those mugs are known as cost of goods sold. Here again, the revenue-expense relationship is clear. When that link is clear, we can determine if a program/service/product is profitable. That is, does the revenue it generates exceed the expenses it uses up? In for-profit organizations, profitability and accountability are virtually synonymous.

But for public organizations profitability has little to do with accountability. For instance, our conservation non-profit might accept donations from individuals in support of its conservation work. Which expenses were necessary to “produce” those revenues? The development director’s salary? The administrator’s travel expenses to go visit a key donor? The expenses from a recent marketing campaign? Here the revenue-expense link is less clear. Same for in-kind contributions (i.e. donated goods and services) the organization receives in support of its mission. This link is even murkier for governments, where taxpayers pay income, property, and sales taxes, but those taxes have no direct link to the expenses the government incurs to deliver police, fire, parks, public health, and other services.

To put this in the language of accounting, public organizations have a mix of exchange-like transactions, such as the backpacking trips and coffee mugs, and many more non-exchange-like activities like conservation programs and public safety functions that are just as, if not more central, to their mission as their exchange-like activities. That’s why profitability is one of many criteria we need to apply when thinking about the finances of a public organization.

Notes to the Financial Statements

GAAP imposes uniformity on how public organizations recognize and report their financial activity. But at the same time, all public organizations are a bit different. They have different missions, financial policies, tolerance for financial risk, and so forth. Also keep in mind that large parts of GAAP afford organizations a lot discretion on how and when to recognize certain types of transactions. For these reasons, numbers in the basic financial statements don’t always tell a complete financial story about the organization in question. That’s why it’s essential to read the Notes to the Financial Statements. The Notes are narrative explanations at the end of the financial statements. They outline the organization’s key accounting assumptions, share its key financial policies, and explain any unique transactions or other financial activity.

That said, the main point of emphasis on the income statement is the relationship between revenues and expenses. As mentioned, net assets are a good indication of that relationship. If revenues increase faster than expenses, then net assets increase. If expenses increase faster than revenues, net assets will decrease. The income statement can help illuminate several follow-up questions to understand an organization’s revenues-expenses relationship at some detail:

- How much did net assets increase since last year? How much of that increase was in unrestricted net assets? How much was in restricted net assets? Growth in unrestricted net assets generally indicates that the organization’s core programs and services are profitable. Growth in restricted net assets can mean many other things.

- What portion of revenue is from earned income vs. revenue from contributions? Earned revenue, or revenue generated when the organization sells goods or services, is attractive because managers have direct control of expenses needed to generate income. Contributions are less predictable and less directly manageable, but do not have an immediate offsetting expense.

- What percentage of earned revenue is from the organization’s core programs and services? What percentage is from other activities and other lines of business? It’s common for non-core programs and services to subsidize core programs and services, but is that the right policy for this organization to pursue its mission?

- To what extent does this organization rely on in-kind contributions? Investment income? In-kind contributions – such as legal services provided to the organization for free by a donor – and investment income make up a smaller portion of overall revenues but often allow the organization report a positive change in net assets.

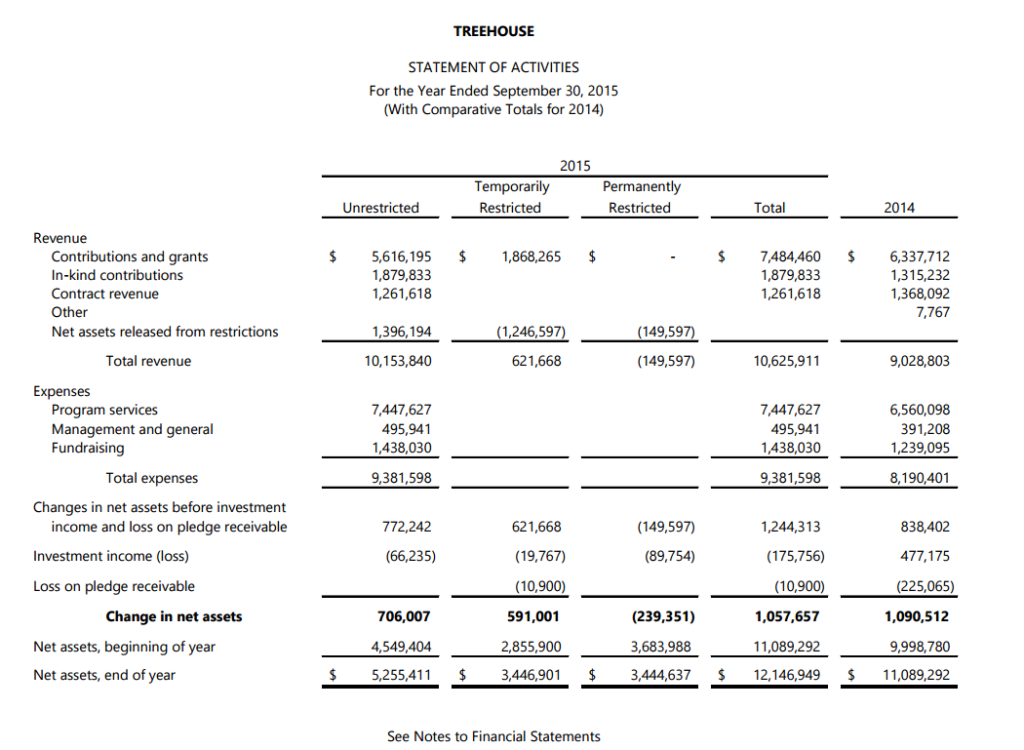

To illustrate, let’s examine Treehouse’s FY2015 Income Statement (i.e. Statement of Activities). Treehouse’s FY2015 Income Statement reports the four most common types of revenues: contributions and grants, in-kind contributions (i.e. donated goods and services), contract revenue, and “other” revenues. The Income Statement reports revenues by restrictions – i.e., unrestricted, temporarily restricted, and permanently restricted. It also reports revenues, expenses, and change for FY 2014.

For FY 2015, Treehouse reported $10,625,911 in revenues. Of that, $7,484,460 was from contributions and grants, $1,879,833 from in-kind contributions, $1,261,618 from contracted revenue and $1,396,194 released from restrictions. Net assets released from restrictions identifies restricted net assets that became unrestricted once the conditions defining the restriction has been met. For example, if a non-profit receives a grant that is temporarily restricted to the provision of specific services to a specific group of beneficiaries, and it delivers those services, it will then convert those temporarily restricted net assets to unrestricted net assets. On the Statement of Activities that conversion will appear as a reduction of temporarily restricted net assets and an increase in unrestricted net assets. These releases do not indicate new revenues, but rather a re-classification across the different types of net asset restrictions.

In reviewing financial statements, we want to take note of important trends. In the case of Treehouse, there was substantial growth in Contributions and Grants — up from $6,337,712 in FY2014, a more than 18% increase.

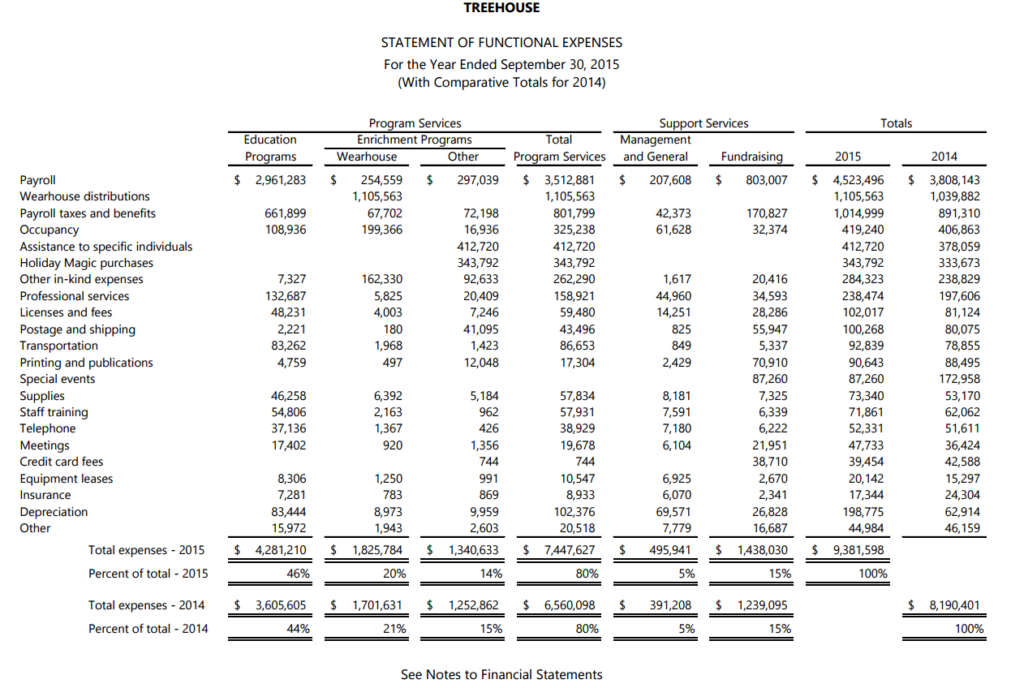

Turning to the expense part of the Statement, we see that expenses for program services (i.e. services for foster children, consistent with Treehouse’s mission) were $7,447,627 in FY2015, nearly 80% of total expenses. Total expenses grew by 14.5% from FY2014 to FY2015, a growth rate that is lower than the rate of revenue growth.

The expenses part also highlights how investment income affected the change in net assets. In FY2015 Treehouse’s investments lost value, and reduced net assets by $175,756. This is a substantial change from FY2014, where those same investments added $477,175 to net assets.

Change in net assets is, as mentioned before, the focal point for the Statement of Activities. To see the change in net assets we compare across the “Change in Net Assets” row. We see Treehouse’s total net assets grew from by $1,057,657, an increase of almost nine percent. Much of that increase is attributable to growth in both contributions and grants and in-kind contributions.

For Governments – The Statement of Activities

A government’s Statement of Activities presents much of the same information we see on the income statement for a for-profit or non-profit. It lists a government’s revenues and expenses or expenditures, and the difference between them. It reports the change in net assets and offers some explanation for why that change happened. Like an income statement, it tells us where the government’s money came from, where it went, and whether its core activities pay for themselves.

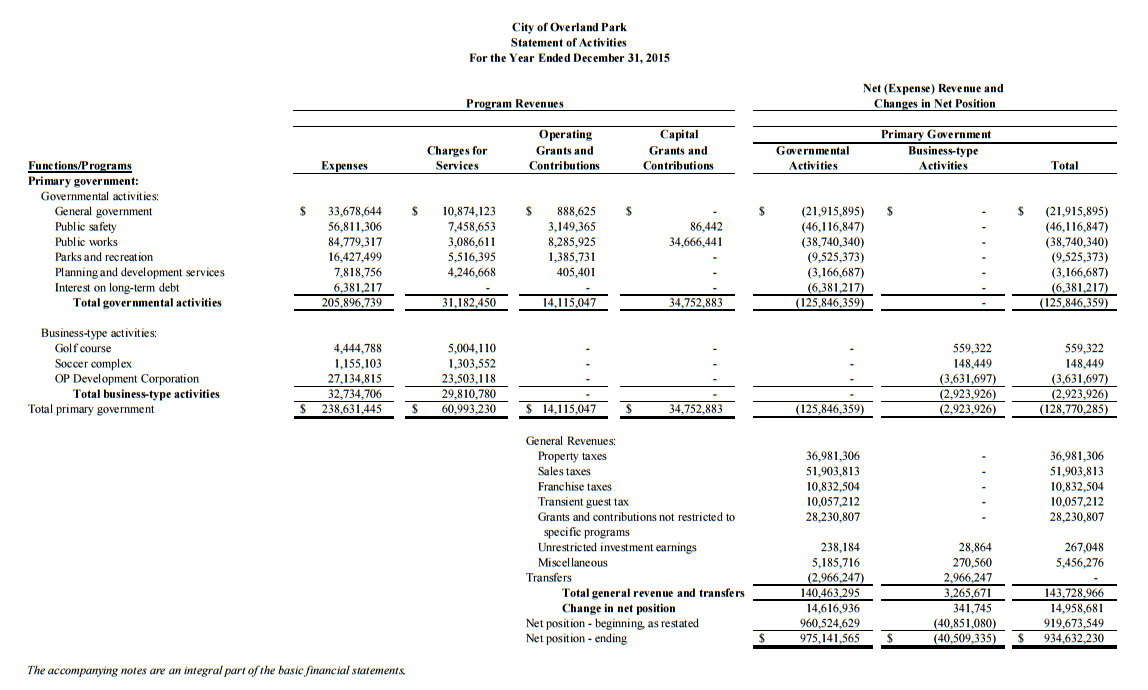

That said, the Statement of Activities is also quite different from a traditional income statement. Expenses in the upper left, are presented by major function or program, with the governmental activities presented separately from the business-type activities. Governmental activities and business-type activities together comprise the primary government. Next to expenses you’ll occasionally see (although not with OP) indirect expenses the government has allocated to each activity (more on this in Chapter 4).

Program revenue includes two types of revenues. One is fees directly linked to these functions and programs for “exchange-like” transactions. OP reported $4.25 million in charges for services for Planning and Development Services. Most of that was building permit fees. As another example, it reported $7.5 million in charges for Services for Public Safety, and that was mostly parking ticket and speeding ticket revenue. And so forth.

Program revenue includes two types of revenues. One is fees directly linked to these functions and programs for “exchange-like” transactions. OP reported $4.25 million in charges for services for Planning and Development Services. Most of that was building permit fees. As another example, it reported $7.5 million in charges for Services for Public Safety, and that was mostly parking ticket and speeding ticket revenue. And so forth.

The other type of program revenue is grants and contributions, which are broken out by operating grants and contributions, and capital grants and contributions. These are usually revenues from other governments. For instance,in 2015 OP received $3.1 million in Public Safety operating grants. Most of that was payments for fire protection services OP delivers to neighboring jurisdictions that lack a full-service fire department. It also received a $34.7 million capital grant from the State of Kansas’ clean water revolving fund for upgrades to its stormwater infrastructure. That money was recorded as a capital grant to Public Works. These are just a few examples of program revenues that governments are likely to report.

Beneath the total expenses and program revenues for business-type activities, we see totals for the primary government. The primary government is the governmental activities and business-type activities combined. It does not include the government’s component units (see below). The primary government plus any component units comprise the government’s reporting entity or the total scope of financial operations covered by its financial statements. OP does not report any component units.

Are We Components?

A component unit is a legally separate entity for which the government is financially accountable. The primary government is financially accountable if it can appoint a voting majority the unit’s governing body, if the component unit can impose financial burdens on the primary government, or if the unit is fiscally dependent on the primary government. Special districts like local development authorities, transportation improvement districts, and library districts are typical local government component units. Common state component units include housing authorities, tollway authorities, public insurance corporations, state lotteries, and state universities.

Most component units are small relative to the primary government. But some are quite large. The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, for example, counts among its component units three casinos, a housing development company, a home health services company, a public health insurance company, a waste management company, a large community foundation, a historic preservation society, and an economic development corporation, among others. In 2015 the total expenses in its primary government were just over $500 million, but the total expenses in its component units were $750 million.

Shifting to the right, we see a group of columns with the heading “Net (Expense) Revenue and Changes in Net Position.” The totals listed here are total program revenues minus total expenses. OP lists a deficit in public safety of $46,116,847. This number is its charges for services plus operating grants and contributions plus capital grants and contributions minus expenses, or (($74,58,653 + $3,149,365 + $86,442) – $56,811,306) = -$46,116,847. This reporting structure is called the net cost format. It nets program revenues from program costs (i.e. program expenses).

This deficit tells us that, not surprisingly, OP’s public safety services do not pay for themselves. Put differently, in 2015 OP had to finance $46 million for public safety using general revenues. We see similar deficits across all of OP’s governmental activities. None of these services are profitable, and the total “deficit” across all governmental activities was $125,846,359.

Should OP’s leaders be concerned that their core services are hemorrhaging money? Not really. We don’t want basic local government services like public safety, planning, and zoning to pay for themselves because there’s not a clear link between the users and the beneficiaries of these services. OP exacts fines on people who break the law when they park illegally or speed on city streets, but those fees are designed to deter those behaviors. Perpetrators who pay these fines really don’t receive a service, and as we saw in Ferguson, MO and elsewhere, bad things happen to local governments that try to turn fines into a viable revenue source.

But that leaves open an important question. Citizens who follow the law and want public safety to keep their community safe are the real beneficiaries of public safety services. How do they help to fund public safety?

To answer that question skip down to the lower right corner of the statement. Here we see a list of General Revenues like property taxes, sales taxes, and others. General revenues are not directly connected to a specific activity. When we add up these general revenues and take away any transfers of general revenues to other parts of OP’s government, the “Total general revenue and transfers” is $140,463,295. Compare that figure to the $125,846,359 “deficit” for the governmental activities, and we’re left with an increase in net assets for the governmental activities of $14,616,936. In other words, OP’s general revenues cover the governmental activities expenses not covered by program revenues, plus almost $15 million more. To put this a bit differently, OP’s core services generate about one-third of the revenues they need to cover their costs. The remaining two-thirds comes from general revenues. This relationship between expenses, program revenues, and general revenues is one of the most important things to observe on a government’s activity statement.

For the business-type activities, this expenses-program revenues link is much clearer. Recall business-type activities are designed to pay for themselves through charges and services. For OP, we see that the Golf Course had net positive revenue of $559,332 and the Soccer Complex had net positive revenue of $148,449. As expected, these activities were profitable. They generated more revenue than expenses. But that was not true for OPDC. It ran a net deficit of more than $3.6 million. Like with the governmental activities, this deficit was covered by general revenues.

Business-type activities present many different challenging strategic and policy questions. How profitable is too profitable? Should business-type activities be profitable enough to subsidize the governmental activities? If a business-type activity like a golf course is not profitable, does it offer enough indirect benefits in areas like economic development and tourism to justify that lack of profitability? With a careful look at the Statement of Activities, you can begin to put numbers to these and other questions.

The Cash Flow Statement

The Cash Flow Statement is just as the title suggests. It tells us how an organization receives and uses cash.

It might seem strange to devote an entire financial statement to a specific asset. But cash is not just any asset. Cash is king. For small organizations, especially small non-profits, it’s possible to run out of cash. If that happens, nothing about that organization’s mission, clients, or impact on society will matter. Its employees, vendors, and creditors won’t take compelling mission statement as a form of payment. If you’re out of cash, you’re out of business. To that end, the Cash Flow Statement is quite useful if we want to answer a few key questions about how a public organization receives and uses cash:

- Do this organization’s core operations generate more cash than they use? If not, why not?

- Does this organization depend on cash flow from investing activities and financing activities to support the cash flow needs of its basic operations? How predictable are are cash flows from investing and financing activities?

- How much of this organization’s cash is tied up in transactions it cannot directly control, such as receivables and payables?

- How much of this organizations’ cash flow is related to sales of goods and inventory? How predictable are those sales?

From the cash flow statement we can learn a lot about the specific ways an organization generates and uses cash. The statement breaks cash flows into three categories: operations, investing activities, and financing activities. Euphemistically, we call this “OIF” (pronounced “oy-f”):

- Cash Flow from Operations. This is how the organization receives cash and uses cash for its core activities. Negative cash flow from operations indicates the organization’s basic operations use more cash than they produce. Without positive cash flow from other sources, this is not sustainable.

- Cash Flow from Investing Activities. In this case investing includes investments in financial instruments like stocks and bonds, and investments in capital assets like buildings. For most non-profits this section is focused on cash earned from investments. If those investments produced more cash than what was spent acquire them, then they produce positive cash flow. Purchases of buildings and equipment are a cash outflow, and if the organization sells any buildings or equipment the receipts from those sales also appear here as a cash inflow. In general, we expect positive cash flow from investing activities. It’s important, however, to know the origins of that positive cash flow. If the organization sold a building, that might produce positive cash flow, but at the expense of its ability to deliver services in the future. It might see negative cash flow from investing activities if, for instance, it moves idle cash into short-term investments.

- Cash Flow from Financing Activities. Financing activities are cash the organization borrows to finance its operations. Most of the activity in this section has to do with borrowed money. For-profit entities use this section of the cash flow statement to show how selling stock produces a cash inflow. For non-profits and governments, the cash inflow from issuing bonds or from taking out a loan will appear here. For non-profits with an endowment or other permanently restricted net assets that produce unrestricted investment income that cash flow will also appear here.

Like with the balance sheet and the income statement, net assets are a key part of most public organizations’ cash flow statement, especially Cash Flows From Operations. It might seem strange that net assets are the point of departure for a statement about cash, but it makes sense if we’re willing to make a few assumptions. Recall that the most common way for net assets to increase is for revenues to exceed expenses. To understand the cash flow statement take this idea a step further. Assume that a public organization’s total cash will increase during a fiscal period if the cash inflows from its main operating revenues exceeds the cash it pays out to cover its main operating expenses. The “Cash Flow from Operations” part of the cash flow statement is based on precisely this idea. It starts with the assumption that an organization’s change in net assets is a good indicator of its cash flows from operations.

Most sizable public organizations follow this concept and report their cash flows from operations using the indirect method. This method starts with the change in net assets, assuming that change is the result of cash flows from operations. But of course, not all changes in net assets are the result of positive or negative cash flow. As you’ll see later in this chapter, many different transactions and accounting procedures can affect revenues or expenses without affecting cash flow. A typical example is depreciation. Depreciation is when an organization “uses up” some portion of an asset in the process of delivering services. The portion of that asset’s value that is used up is recorded as a depreciation expense. Like all expenses, depreciation reduces net assets. But at the same time, there is no cash flow associated with depreciation. You won’t find any checks written to an entity called “Depreciation.” The same is true for changes in the value of an organization’s investments. Its stocks, bonds, and other investments can increase in value, but unless it sells those investments that increase in value won’t produce any positive cash flow. Depreciation and changes in the value of investments are both examples of reconciliations. These are transactions that affect net assets but do not involve a cash flow.

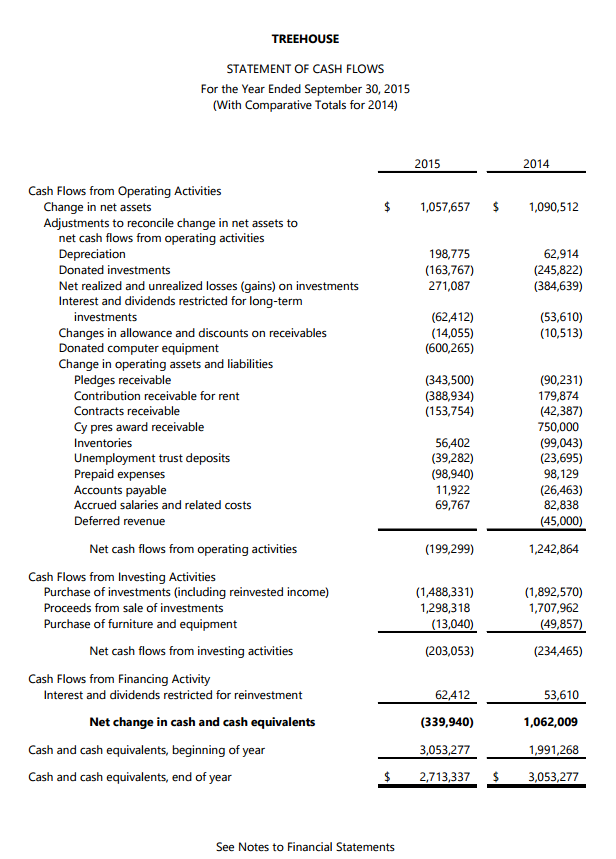

In FY15 Treehouse produced its Statement of Cash Flows according to the indirect method. In the second column of the statement you can see that its net assets increased by $1,057,657 from the start of FY2015 (October 1, 2014) to the end of FY2015 (September 30, 2015). Skip down to the row “Net cash flows from operating activities” and you’ll see that in FY2015 Treehouse’s operating activities resulted in a net cash outflow of $199,299. In other words, the cash its operating activities used was almost $200,000 more than the cash those activities generated. This begs a natural question: How could Treehouse have more than a million dollars of new net assets even though its basic operations lost $200,000 of cash? This seems inconsistent with the idea that growth in net assets will correlate with growth in cash holdings.

To answer this question look at the reconciliations in the third/fourth row (i.e. “Adjustments to reconcile change in net assets to net cash flows from operating activities”). Recall that the figures in this part of the statement are reconciliations, so we interpret them inversely. Activity that would otherwise decrease net assets is shown here as an increase because we’re “adding back” those decreases to arrive at net cash flows from operations. Activity that would otherwise increase net assets is shown as a reduction (in parentheses) because we’re “backing out” those increases to arrive at net cash flows from operations.

Treehouse reported several reconciliations in FY2015, but a few of the larger ones deserve special attention. We see that Treehouse’s net assets increased because it received $163,767 of donated investments and $600,265 of donated computer equipment. These two transactions alone increased net assets by $764,032, but did not produce any positive cash flow. Computer equipment is equipment, not cash. Investments increase the asset called investments, but do not immediately result in a cash flow. So we can see how net assets can increase substantially without any change in cash flow. The opposite is true for depreciation and an unrealized loss on investments (i.e. when the market value of an investment is less than the book value, also known as a “paper loss“; the opposite is also true for unrealized gains or “paper gains” on investments). These reconciliations decreased net assets by $198,775 and $271,087 respectively, so here they are added back to total net assets.

Below the reconciliations you’ll see “Change in Operating Assets and Liabilities.” The figures listed here are also reconciliations, this time to reconcile changes in assets and liabilities that do involve cash to changes in net assets.

The key here is we’re focused on assets and liabilities driven by cash flows. So to make sense of the Change in Operating Assets and Liabilities section, first think about how typical assets and liabilities interact with cash. Most assets will increase if cash decreases. If we purchase inventory with cash, for instance, inventory will increase and cash will decrease. It follows that decreasing an asset will almost always bring about an increase in cash. For example, if we sell marketable securities or collect on accounts receivable, those assets will decrease, but cash will increase. When liabilities like loans or a mortgage increase, so does cash (otherwise, most increases in liabilities don’t correspond to a cash flow). When we pay down an account payable or a loan payable, cash decreases.

Now, recall that with the indirect method, the goal is to arrive at cash flows from operations by adjusting changes in net assets. To that end, we need to undo the effects of these asset/liability changes on net assets, this time focusing on how cash flows affect those specific types of assets and liabilities. The table below lays out how these reconciliations work.

| Change in Asset/Liability | Reconciliation |

| Asset account increases | Reduce Net Assets |

| Asset account decreases | Increase Net Assets |

| Liability account increases | Increase Net Assets |

| Liability account decreases | Decrease Net Assets |