Module 3: Course Design and Implementation

Essential Considerations for Online Course Design

Lauren Anstey

Online pedagogy and in-person pedagogy are fundamentally different, requiring vastly different methods. Additionally, post-secondary institutions are being called upon to consider important and foundational priorities, such as universal design, anti-racism, and reconciliation. This unit will orient you to those essential considerations and methods that not only define online teaching, learning, and assessment but also shape the future of Ontario universities and colleges.

This unit does not attempt to replicate the vast wealth of knowledge available in guiding on the essential considerations presented here. What it does aim to do is orient you to this wealth of knowledge so that you can get a sense of the big picture and lead program and course design with these essential considerations in mind. In other words, this unit offers guidance for tapping into essential considerations for your deeper exploration and application.

Much of this knowledge and expertise might very well come from your own team. Unit 1 in this module, “Start with Collaboration” as well as “Collaborating to Create the Online Learner Life Cycle and Its Ecosystem” in Module 1, introduced you to the various units, roles, and positions often involved in online course design and development. There is a strong link between the various roles represented in those lists and the essential considerations of this unit. Your team and those you consult with throughout course design each bring their own wealth of knowledge related to the essential considerations presented here. Their work serves to navigate, incorporate, and focus on these pieces throughout the course design process. While this module unit might orient you, it’s the members of your team who will bring unique and valued perspectives on these considerations in application to your program, courses, and institutional contexts.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Reflect on seven interconnected and essential design considerations and apply them to your own plans for online course design

- Identify next steps for tapping into the wealth of resources and expertise that allow for essential considerations to be enacted within course design

You will come away with:

- An understanding of the interconnected landscape of essential design considerations for online course design

- An appreciation for the resources (within the design team and beyond) that can help prioritize selected essentials into online course design

This unit focuses on the Feedback, Continuous Improvement, & Sustainability; Educational Technology Stack; Instructional Design & Educational Technology Expertise; Course Design; Teaching and Learning; Course Design; Faculty Expertise & Readiness; Student Support Systems; and Policies and Procedures elements of the Online Program Ecosystem. Read more about the ecosystem in Module 1, Unit 1: Collaborating to Create the Online Learner Life Cycle and its Ecosystem

There’s a common fallacy that online courses are identical to in-person or face-to-face classes: that they are the same but just happen online. Inexperience and rushing to get something up and running often cause online course designers and instructors to overlook some of the key differences between these modes of teaching and learning (Baldwin & Ching, 2019). By focusing on seven interconnected and essential design considerations for online courses, teaching, and assessment, program leaders can mitigate this fallacy and truly design for online.

Additionally, some considerations presented here take essentials beyond the uniqueness of online pedagogy to the broader intentions and goals of teaching and learning in higher education. As universities and colleges shift in response to global priorities, all academic leaders must hold their programs accountable to what is taught, valued, and prioritized.

Introducing the Essential Considerations of Online Course Design

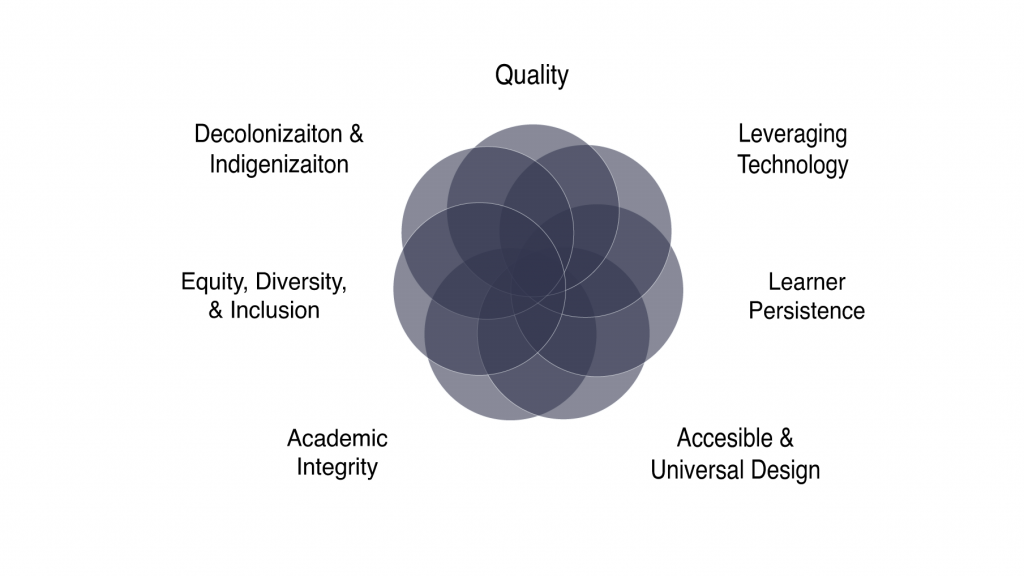

What are these seven essential considerations? Click on each consideration below for a description.

- Quality

- Leveraging Technology

- Learner Persistence

- Accessible and Universal Design

- Academic Integrity

- Decolonization and Indigenization

- Equity Diversity, and Inclusion

These considerations are inextricably linked. In focusing on one, the connections to other considerations are soon illuminated. For example, the characteristics defining quality for online courses necessarily involve elements of accessible and universal design. In this first section, each consideration is briefly introduced. Following this section, each consideration is brought to the foreground for elaboration, where we introduce foundational concepts, recommend follow-up resources, and prompt reflection for deeper exploration and application.

Quality

What constitutes a high-quality online course? How do we measure, deliver on, and guarantee a quality online course? These essential questions have driven many groups to develop standards and rubrics as guidelines and measures of high-quality online teaching and learning.

Common sources include Quality Matters, Online Learning Consortium, or Institutionally-developed Frameworks, such as Seneca College’s Quality Framework for Designing and Delivering Online Courses and The University of Waterloo Quality Guidelines.

Despite the various frameworks available, they all share the common goal of organizing elements of high-quality online education to support designers, instructors, and academic leaders in their design and development of online courses based upon and measure quality standards. While different frameworks offer specific ways of organizing and presenting criteria, they often integrate the essential considerations highlighted throughout this unit, such as active teaching and learning; accessibility and Universal Design; equity, diversity, and inclusion considerations; and elements of learner persistence.

Reflection

- What characteristics will shape your program’s definitions of high-quality online education?

- How will you measure and guarantee the quality of your online courses?

- Which frameworks or tools will your group engage?

Teaching and Learning-Driven Technologies

What is evident through the various quality frameworks is that the learning environment and students’ engagement in learning or assessment activities are different than that of in-person contexts. Everything in an online course is mediated through digital technologies – from the internet to the Learning Management System (LMS), to educational technology tools that allow for creative engagement.

Online educators often seek to leverage various online tools and technologies in a purposeful way. It’s important that teaching and learning drive technology use, not the other way around. In other words, educational technologies should serve the identified goals/needs of learning and student engagement, rather than selecting the technology first and allowing its parameters or limitations to dictate learning.

The Instructional Designers and Multimedia Specialists on your team can support conversations that expand ideas for teaching, learning, and assessment in ways that are not only aligned with the intended outcomes of the course but creatively and meaningfully engage digital technologies. Tools such as the eLearning Toolkit and Rubric for eLearning Tool Evaluation can also help you choose and assess tools that align with your program vision and outcomes.

Reflection

- What tools and technologies have already been identified for the program and course development?

- What recommendations do your team members have to make about the tools and technologies the program and its courses should use?

- How might students be encouraged to participate in active learning through the use of technology and eLearning tools?

- Do assessment technologies or digital assignments support authentic assessment of knowledge and skills?

- How do your measures of Quality aid you in accounting for technologies that are driven by teaching and learning needs rather than the other way around?

Learner Persistence

Online learning can place learners in an unfamiliar space where new ways of engaging and learning are demanded of them. They often must unlearn or adjust longstanding learning habits and develop new approaches (Abdous, 2019). Oftentimes, online programs wish to recognize that their students are adult learners attracted to online studies for the flexibility it will grant. How do we motivate online learners to persist with their learning? What scaffolded supports and curricular structure will encourage self-directed, goal-oriented approaches, where appropriate? Learner persistence is understood as a multi-faceted phenomenon that leads to the completion of an online program of study (Hart, 2012).

Reflection

- How will your courses support students to persist with their learning?

- How will you leverage the facilitators and reduce the barriers to persistence?

Accessible and Universally Designed

Online and digital technologies afford entirely new ways of teaching and learning that were once inconceivable. Though, the way we use technology matters. It is not automatically more accessible than other modalities; it must be intentionally designed as such. This consideration focuses on both accessibility requirements (such as AODA) as well principles of universal design where the learning environment can be accessed, understood, and used to the greatest extent possible by all people.

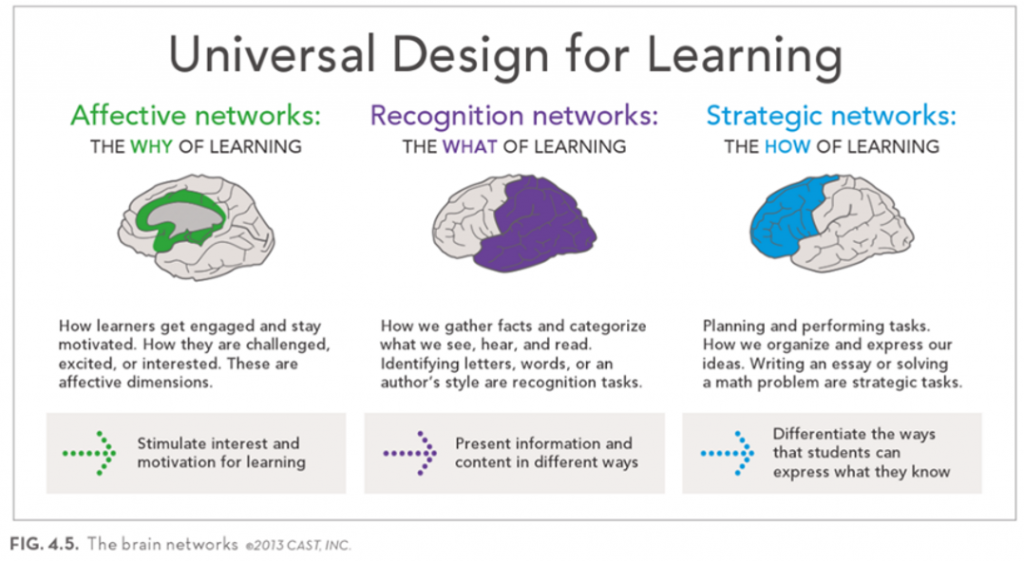

In addition to AODA requirements, designers often turn to Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is a “framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn” (CAST, n.d.). Guidelines are organized around three elements: Engagement (the why of learning), Representation (the what of learning), and Action & Expression (the how of learning). UDL guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities. The UDL framework is often employed by course designers to apply these concrete suggestions directly into course design. By focusing on UDL, many aspects of accessibility for students with disabilities are inherently addressed. It is important to consistently address accommodations, as those who experience barriers due to disability, reduced capacity, or extenuating circumstances face unintended barriers to learning.

Reflection

- What actions and additional resources are required for ensuring courses are accessible to all learners?

- How will concepts of accessibility and universal design be represented in your program and its courses?

- What will be the tone of course accommodations policies?

- How can courses engage multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action & expression?

Academic Integrity

Instructors are often concerned that online courses create conditions that allow students to cheat on their assignments more easily. Online environments do pose challenges but these challenges can be overcome with purposeful design of instructional activities and assessments. Many of the best practices that encourage students’ academic integrity in face-to-face contexts equally apply to online courses.

One example resource offering strategies for promoting academic integrity in online contexts is The University of Waterloo’s Centre for Teaching Excellence (n.d).

Reflection

- What are the academic integrity practices at your institution?

- Do you have policies or guidelines for academic integrity specifically for online courses?

- What practices will set students up for success in understanding and engaging with academic integrity?

Decolonization, Reconciliation, & Indigenous Empowerment

Education for Reconciliation – this is the title of the TRC Calls to Action section that calls upon post-secondary institutions (with support from governments and in collaboration with Survivors, Aboriginal peoples, and educators) to integrate Indigenous Knowledges and teaching methods into classrooms. Integrating Indigenous Knowledges and methods into the online classroom is one part of the broader activity of decolonizing curriculum, education, teaching, and learning.

Consider this text from Fuentes et al., (2021, p. 75):

“Decolonization, or anti-colonialism, can be defined as resisting, transforming, and eradicating the oppressive hegemonic power structures that influence our ways of acquiring and transmitting knowledge (Stein & de Oliveira Andreotti, 2016). Additionally, it involves critical consciousness and awareness, accountability, and reclaiming power that has been usurped from marginalized communities (Dei, 2006). It is also important to note the roots and origins of the construct of decolonization and credit these efforts to Indigenous communities (Dei, 2006) and Black enslavement liberation efforts (Stein & de Oliveira Andreotti, 2016).” (Fuentes et al., 2021, p. 75).

A list of strategies, recommendations, or approaches to decolonizing your program, courses, or teaching is purposefully not provided here. No such list could adequately convey the specific considerations for this work as situated within your context. What can be suggested is that academic leaders seek out and listen to a wide variety of voices:

- Reviewing and meaningfully incorporating Institutional materials developed to guide the college or university on decolonization and Indigenization, for example, Indigenous Learning Outcomes expressed by your college or university

- The literature arising within your disciplinary context as to the engagement in decolonization and Indigenization within the field

- Collaborating with Indigenous scholars and/or Indigenous Educational Developers

- Connecting with campus-based Offices/Centres of Indigenous initiatives, culture, or studies

- Connecting with Elders and Indigenous community members

The Pulling Together Learning Series are six texts for audiences such as Teachers and Instructors, Leaders and Administrators, and Curriculum Developers in Indigenizing Post-Secondary Institutions. These materials are a recommended next step in considering what decolonization and Indigenization look like within your program and courses.

Finally, as has been prompted in other sections, consider how decolonization is both a lens for designing and building courses as well as a lens for informing the content of what is taught. How are students called upon and educated to deconstruct the colonial ideologies of superiority and privilege that Western thought/approaches have shaped?

Reflection

- What are your next steps in considering decolonization and Indigenization in your program and course design?

- Who can you collaborate with?

- What does reciprocal and meaningful collaboration look like to you?

- How will you facilitate comfort amongst the team (e.g., instructors, subject matter experts) regarding such inclusion?

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

How do instructors and academic learners of the program work toward ensuring fair and equitable treatment, access, and opportunity for all learners? How does learning reflect various identities and differences? How do we create online learning environments that foster students’ sense of inclusion, where they are respected and valued?

In the guide, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Online Teaching: Where to Begin?, the authors write: “Paradoxically, without an EDI lens, online learning, which is often assumed to make learning more accessible, can exacerbate pre-existing inequities. Similar to in-person learning environments, online learning involves widely varying levels of access to technology and resources as well as different student accessibility needs” (University of British Columbia, n.d.).

Like accessibility, EDI might also be a lens through which to review the curriculum/content of the program itself. How are the program and its courses teaching students to know, value, or engage with concepts of equity, diversity, and inclusion within the professional, vocational, or academic setting of study?

Reflection

- How will you work toward ensuring fair and equitable treatment, access, and opportunity for all learners?

- How will learning in your course and the program reflect various identities and differences?

- What will you specifically do to create online learning environments that foster students’ sense of inclusion, where they are respected and valued?

Unit Reflection and Resources

This unit has prompted your consideration of seven interconnected essential considerations:

- Quality

- Leveraging Technology

- Learner Persistence

- Accessible and Universal Design

- Academic Integrity

- Decolonization and Indigenization

- Equity Diversity, and Inclusion

As you reflect on the unit as a whole, consider the intersectionalities between these considerations. How do you see them connecting and weaving together to inform program and course design?

This unit has focused on how essential considerations inform course design, while inevitably pointing to the wider program design as a place where these considerations may also be addressed. As an academic leader, try identifying where the onus lies – is it up to individual instructors and courses to reflect these considerations? Or does responsibility also extend to the program as a whole? How can the program design offer overall guidance and structure such that these considerations can be effectively exercised at the course level?

Actionable Tasks

This unit opened with a nod to the knowledge and expertise related to these considerations that frequently come from within your team. Your team and those you consult with throughout course design each bring their own wealth of knowledge related to the essential considerations presented here. Their work serves to navigate, incorporate, and focus on these pieces throughout the course design process.

What actions will you take next to prioritize these relationships in centring the considerations presented in this unit within program and course design?

Unit Resources

This unit purposefully stops short of elaborating on the next steps of building, planning, and teaching online courses. There are many excellent open educational resources that pick up where we’ve stopped. We point to a sample of those rather recreate what many before us have done, and done so well

Online Course Design

Teaching Online

Learning to Learn Online: Student Learning Supports

Characteristics and measures that are commonly used to define high-quality online courses. Quality indicators are frequently presented as rubrics or tools that can guide design, assessment, or continuous improvement of high-quality in online education.

A consideration of the technology-enabled teaching, learning, and assessment strategies best suited for online courses and programs. It also involves considering how technologies can be evaluated and selected for their appropriateness and best fit for teaching and learning.

Drawing on adult learning theory, this consideration focuses on strategies that meaningfully engage, support, and motivate online learners to take self-directed, goal-oriented approaches to their learning so that they are more likely to persist and succeed through their online learning.

Accessibility requirements, such as the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) in Ontario, are one part of universal and accessible design. AODA legislation stipulates that “all public sector organizations and private or non-profit organizations with fifty or more workers must make their courses accessible to all learners”. Universal design means creating course environments that are accessible to all people, regardless of ability, disability, age, or other factors. Accessibility means course environments are adaptable and functional for users of all abilities (Grimard, 2021).

Academic Integrity focuses on the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage as guiding academic work, exploring how online learning environments can be purposefully designed to reduce instances of student misconduct and instead foster their integrity.

Decolonization and Indigenization are the terms selected for this unit in representing a commitment to Truth and Reconciliation, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action that call upon educators to learn about and integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms. Here, the essential consideration is focused on decolonization as “the process of deconstructing colonial ideologies of the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches”, and Indigenization as “a process of naturalizing Indigenous knowledge systems and making them evident to transform spaces, places, and hearts” (Antoine et al., 2018).

Three distinct but interwoven concepts are introduced together in a common focus on EDI. Equity represents fair and equitable treatment, access, and opportunity through learning. Diversity focuses in on diverse representation of various identifies and differences. Inclusion represents efforts engaged to create learning environment where students feel included, welcomed, respected, and valued.