Module 3: Course Design and Implementation

Curriculum Mapping

Lauren Anstey

This unit uses case studies to illustrate various approaches to curriculum mapping. It expands upon the previous unit, “Turning Program Vision Into Curriculum,” to introduce the what and why of curriculum mapping.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Identify key features of your own curriculum mapping approach, as inspired by example curriculum maps

- Plan for a curriculum mapping approach that will enable decision-making such as:

- What courses happen when and how in the program;

- What teaching and learning activities and major forms of assessment fit with each course in the program and why; and

- What materials you will need to develop or source for each course you’re planning such as instructional content, teaching and learning activities, multimedia, assessment materials, rubrics, syllabi, and more.

- Reflect on the current state of course-level planning, design, and development

You will take away:

- A draft curriculum map that aligns program outcomes with what is currently known of course design within the program

This unit focuses on the Program Outcomes, Course Design Teaching and Learning, and Faculty Expertise and Readiness elements of the Online Program Ecosystem. Read more about the ecosystem in Module 1, Unit 1: Collaborating to Create the Online Learner Life Cycle and its Ecosystem

There is no one correct way to engage in curriculum mapping. Curriculum mapping is “the process of associating course outcomes with program‐level learning outcomes and aligning elements of courses (e.g., teaching and learning activities, assessment strategies) within a program, to ensure that it is structured in a strategic, thoughtful way that enhances student learning” (Dyjur et al., 2019, p. 4). The process and output (the map itself) ought to be flexible in context of the designers, their curriculum, and the unique conversations that drive the development of their curriculum map.

Given this variability and the conversational nature of curriculum mapping, we employ a case study approach in this unit to illustrate the nuances of curriculum mapping while also illustrating the process.

Introducing the Case Studies

Throughout this unit, we present three different case studies. Read the short description below and consider which case might resonate most closely with you.

Case Study I follows program leader, Sam, as they build a curriculum map for a new online undergraduate certificate in Biology Research with a case study approach as the program’s signature pedagogy. Case Study I reflects development of a new program where a new curriculum is being envisioned with no pre-existing courses in mind.

Case Study II follows program leaders, Amanda and Brian, who are working together to design a competency-based Tourism Management program. This case study is inspired by a paper published by Cecil and Krohn (2012). Case Study II is similar to Case Study I but with a different industry/disciplinary and curricular focus.

Case Study III follows program leader, Eric, who is creating a new online program by taking an existing in-person Germanic Studies program and transitioning it to a revised and reimagined online program. This case was inspired by a paper by Metzler et al. (2017). In this case, Eric and his team were working with pre-existing courses and course content that could inform their mapping.

Pre-Check: Assess your Readiness for Curriculum Mapping

Before entering into a curriculum mapping exercise, it’s best that:

- Program-level learning outcomes have been finalized (See Module 2: Planning Out the Program)

- The overall curriculum vision has been articulated (See Module 3: Turning Program Vision Into Curriculum)

Reflection: Recording Initial Thoughts

- What are you already working with?

- Pre-existing courses?

- Previously identified ideas for new courses?

- How do you imagine students will progress through the program?

- What will they need to learn or do, and when?

Progression of Learning

The first step of the mapping process is to consider the progression of learning. This refers to how students’ learning develops and builds across the program, i.e., how they go from incoming students to graduates able to demonstrate achievement of program learning outcomes. Progression of learning considers how learning advances, changes, or deepens as learners progress through the program of study.

Consider working with a selected Taxonomy of Learning or a combination of Taxonomies, which give educators a structure and language for considering what deepening or advancing on learning looks like over time. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a very common source. In addition to Bloom’s or in compliment, designers might also explore:

- SOLO Taxonomy (Biggs & Collis, 1982)

- The ICE Model (Fostaty Young & Troop, 2022)

Click through the models of these taxonomies below.

Image 2: SOLO Taxonomy, Doug Belshaw, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 3: ICE Model, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, via Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Across the Disciplines: ICE Stories.

Let’s turn to our case studies to see how a conversation about the progression of learning helped designers get started with their curriculum mapping.

Case Study I: Progression of Learning of evidence-based decision-making in Biology Research

Sam was working to develop a new online undergraduate certificate in Biology Research. With their team, Sam had previously articulated program learning outcomes and identified case-based learning as the program’s signature pedagogy. When Sam sat down to consider the progression of learning, one program outcome immediately came to mind: Students will be able to use biology research to make evidence-based decisions, and Sam decided to start there.

Sam thought to themselves, “This is an easy one. I know students will be starting the program with very little sense as to what constitutes research within the field, so we’ll be starting from the basics. Before students can start developing the skills to use research for decision-making, they will need to appreciate what Biology research is and how we determine what’s research over other forms of knowing within the field. From there, we can support students in developing the skills of evidence-based decision-making, but these skills take practice over time.” Sam paused to think about this in relation to case-based learning.

“This works well for a case-based approach,” they thought, “I think the program should start with small opportunities to practice through cases and build from there. Ultimately, I know we’d like to see students completing major assignments towards the end of their program that demonstrate their evidence-informed decision-making–again this is best done through cases. That way students can show one another what evidence-informed practice looks like in a variety of academic and professional settings and through a variety of perspectives.”

Case Study II: Progression of Learning for a competency-focused on tourism business operations

When Amanda and Brian began designing their Tourism Management program, they identified three broad principal categories for learning related to the work done by the Program Learning Outcomes team:

- general business operation principles,

- principles of tourism and event management, and

- principles of professional and life skills.

Under each broad category, they had identified competencies. For example, under the first category of general business operation principles was a competency of being able to effectively manage a business by implementing organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives. Through program and curriculum visioning, the developers had also begun to shape their curriculum design by identifying three learning domains for the program: Domain 1: Foundations, Domain 2: Application, and Domain 3: Execution.

Their next step was to consider the progression of learning by asking what would learning look like across the curriculum as students developed this competency? How would students progress from Foundations to Application to Execution?

Amanda: “Students need to be competent with implementing a tourism organization’s vision, mission, goals and objectives. That’s what it looks like to execute this competency.”

Brian: “Right. Implement and critique, I would add. In order to get to that level of performance, students will need to know what qualities make vision, mission, and objectives of organizations effective or successful. I guess it’s also about being able to plan and operationalize objectives based on the organization’s vision and mission.”

Amanda: “For sure. That’s all part of managing the business and implementing its mission. The Foundations are being able to identify components of successful vision and mission statements, the application is being able to operationalize it, and the final outcome of learning, the execution, is being able to implement and critique.”

Case Study III: Progression of Learning in Germanic Studies courses

To revitalize a Germanic Studies program and attract a new demographic of students, Program Leader Eric began working with a small team of faculty colleagues and educational developers to take the existing program structure and reimagine it for a New Program Proposal as a revitalized, made-for-online Germanic Studies program. The team had lots to draw from as they set out with their planning – they reviewed the existing program outcomes and decided the online program would uphold the same intentions.

Regardless of modality (in-person or online) the goals and intended outcomes of the program would remain the same. For example, the program goal of Cultural Understanding and Awareness aligned with three program learning outcomes:

- Describe the values of one’s own culture

- Articulate the cultural perspectives of others

- Evaluate the values of another’s culture

The team knew the new online program would involve four core courses, similar to the in-person version. Eric sat down with the faculty instructors who had previously taught the in-person courses. “I think we can all agree, these outcomes have been taught in various ways through the courses you’ve each taught. However, the new online program is a chance to take a closer look at the curriculum, take a collaborative approach, and consider new approaches – especially to teaching and assessments that could strengthen our values of engaged and active online learning.”

Through conversation, instructors discussed how they had been teaching elements of the goal: Cultural Understanding and Awareness, and where they could address gaps and redundancies in redesigning for online. For example, they agreed that Course W introduced novice students to articulating the cultural perspectives of others, while Course X assumed that introduction and focused more on the intermediate and advanced elements of that skill. They also agreed that Course Z was a great place for students to demonstrate advanced performance of Outcomes 1 and 2, but that the program had been missing an opportunity for advanced performance of Outcome 3. They noted the online program was an opportunity to address this curricular gap.

Drafting Curriculum Maps for Emerging Course Structure and Design

There is no ‘right’ way to map a curriculum. The curriculum maps you might aim to develop at this initial stage of design will be shaped by the unique context of your work. In this section, we pick back up on the three case studies of this unit to exemplify three different approaches to curriculum mapping. Your curriculum map may take inspiration from one or all these examples. Alternatively, you may devise new ways of representing your unique curriculum in a way that best serves your course development process.

Case Study I: Organizing a curriculum map for evidence-based decision-making in Biology Research

Recall that Sam began by focusing on one program outcome and identified how students would progress on their learning toward it. Based on Sam’s reflections, Sam created a curriculum map to represent their initial ideas:

|

Program Outcome |

Early in the Program |

Mid-Program |

Late in the Program |

|

Students will be able to use Biology research to make evidence-based decisions |

Identify what constitutes research in the field of Biology

|

Introduction and rehearsal of component skills that lead to an ability to make decisions informed by research |

Culminating assignments where evidence-informed decision making is critical to success |

Table 1: A draft curriculum map displaying the progression of learning for one program outcome in the Biology Research Program.

Sam’s thoughts were organized into ideas for early in the program to more complex learning at the end. Notice how Sam’s map has not elaborated on any specific courses of the program at this time. What Sam is noting is that, sometime in the course(s) that come early in the program, students will need to learn an ability to identify research. Later in Sam’s planning, Sam can collaborate with others to decide which course or courses this type of performance could be included, how it would be taught, and how it would be assessed.

Given that Sam and their team had previously identified case-based learning as the program’s signature pedagogy, their curriculum mapping progress could be further informed by the literature in generating ideas for teaching evidence-based decision-making through a case-based approach.

Case Study II: A Curriculum Map for Tourism Management

Amanda and Brian moved from their progression of learning conversation to curriculum mapping by drawing on their established curriculum structure of the three domains – Domain I: Foundations, Domain II: Application, and Domain III: Execution. They had an overall sense of how learners progressed across these domains for each of their competency outcomes and refined their ideas by organizing them in a table:

|

Principle Category: General Business Operation Competency Outcome: Effectively manage a business by implementing organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives |

|||

|

Task within management competency |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain I: Foundation |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain II: Application |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain III: Execution |

|

Organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives |

Identify components of successful vision, mission, and objectives |

Plan operational objectives to meet the mission, goals, and objectives of the organization |

Implement and critique organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives |

Table 2: A draft curriculum map for Tourism Management that organizes the progression of learning from foundations to application to execution as related to one learning outcome.

Amanda and Brian’s map is like Sam’s map from Case Study I, though different in the way it organizes the map upon a selected, and more specific, curricular structure. Note how this map also remains focused on broad rather than granular details about the courses.

Case Study III: Mapping Courses in Germanic Studies

Eric and his faculty colleagues had discussed how courses across the program related to their various program learning outcomes, identifying where learning was introduced, reinforced or culminated in advanced performance. They had also identified opportunities to address gaps they had noted of their in-person program.

The group captured the nuances of that conversation in a curriculum map that plotted the overall goal and the three related outcomes to the four core courses they were working with. In this curriculum map, they used the following three levels of learning:

- N = Novice. “The course introduces students to important concepts and disciplinary thinking. The level is intended for students who have no previous experience with the material.”

- I = Intermediate. “The course is pitched to students who have taken at least one previous course in the discipline. It is for neither novices nor advanced learners.”

- A = Advanced. “The course is designed for students who have taken several courses in the discipline and are well familiar with the basic concepts, theories, and terminology of the discipline.” Metzler et al. (2017)

| Program Goals | Program Student Learning Outcomes | Course W | Course X | Course Y | Course Z |

| Cultural Understanding and Awareness | Describe the values of one’s own culture | N, I, A | A | ||

| Articulate the cultural perspectives of others. | N | I, A | A | ||

| Analyze the values of another’s culture. | N, I | N, I, A |

Table 3: A NIA (Novice, Intermediate, Advanced) Curriculum Map for Germanic Studies, as adapted from Metzler et al. (2017). This map shows four core courses of the program (Course W – Z) and whether each course addresses novice (N), Intermediate (I), or Advanced (A) levels of learning.

Eric and his group used language that felt comfortable to them. Common alternatives to this language include:

- I = Introduce. The course introduces students to knowledge, skills, or values related to the performance of the learning outcome

- R = Reinforce. The course builds upon knowledge, skills, or values already introduced to students. It’s assumed that students have some prior knowledge that is then reinforced.

- P = Proficient. The course supports students to demonstrate proficiency in the learning outcome.

I, D, A:

- I = Introduce

- D = Developing

- A = Advanced

I, D, C:

- I = Introduce

- D = Developing

- C = Culminating/Capstone

While the language communicates essentially the same meaning, different groups will find some words resonate over others. If you’re attracted to this approach of curriculum mapping, seek to clarify with colleagues what language you will use as a team and clarify understandings before beginning the mapping process.

Like Case II, this map remains focused on broad rather than granular details about the courses. What Eric’s team was able to map was that Course W, for example, will introduce students to the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes needed for articulating the cultural perspectives of others. Course X will expand on this learning and support students in advancing their abilities. Course Z will serve as a capstone for the program where the learning will be practiced at an advanced level. Later in the design process, these broad details of each course will then guide further course design planning, such as how instructors of Courses W, X, and Z will plan for teaching and learning activities that enable the targeted level of learning and how students will be assessed.

Getting Granular: Elaborating on Course-Level Learning Outcomes and Constructive Alignment within Courses

Work to expand upon, add detail, or refine upon the overall progression of learning by building in further detail about course-level curriculum. Your map might seek to include:

- Course-level learning outcomes mapped to program outcomes

- Major forms of teaching and learning activities (e.g., lecture, case-based learning, experiential learning) specific to individual courses

- Major forms of assessment, both at the course level (e.g., essay assignment, presentation) and/or as capstone assessments (e.g., a portfolio produced over the program)

Case Study I: Where Outcomes are Taught and Assessed in Biology Research Courses

Sam’s initial draft map helped frame conversations with others – faculty instructors, educational developers, and instructional designers who had come together to support the Biology Research online certificate. Through multiple rounds of conversation, the team got to the point where their curriculum map significantly advanced upon Sam’s first draft.

|

|

Learning Outcome 1: Students will be able to use Biology research to make evidence-based decisions

|

Learning Outcome 2 | Learning Outcome 3 | … | ||||||

|

Progression of learning |

Identify what constitutes research in the field of Biology |

Introduction and rehearsal of component skills that lead to an ability to make decisions informed by research |

Use Biology research to make evidence-based decisions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Courses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

BIOR-100 |

T&A |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

BIOR-101 |

T |

T&A |

T |

|

|

|

||||

|

BIOR-202 |

A |

T&A |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

BIOR-374 |

|

|

T&A |

|

|

|

||||

|

BIOR-400 |

|

|

A |

|

|

|

||||

Table 4: An advanced curriculum map for the Biology Research Program illustrating an example of how specific courses have been mapped to the program learning outcome and specified progression of learning milestones. Courses are mapped based on whether the outcome is taught (T), assessed (A), or taught and assessed (T&A).

They had taken Sam’s outcome and progression of learning and adapted it into a new table as they worked. The group knew they had to get detailed as to what courses would either teach, assess, or both teach and assess the outcome. Sam’s notes on progression of learning helped here. For example, it was easy for the group to recognize that BIOR-100 should both teach and assess students’ ability to identify what constitutes research.

Notice how their map indicates where the outcome may be only taught or only assessed. This made sense to the group as well as they reviewed their ideas for the progression of learning. For example, they knew that students took BIOR-374 before BIOR-400. It was acceptable then that BIO-374 would teach and assess the culminating performance of using research to make evidence-based decisions where BIOR-400 was heavily focused on assessment alone.

This map served as the guide for subject matter experts and instructors who would go on to develop each of these courses. They had the initial blueprint to know that the specific courses they were developing needed to include aspects of teaching and/or assessment. This opened up further conversations as to how and with what resources/technologies this would occur. As syllabi were planned and course resources were developed, the team could refer back to this map to inform their decisions.

Case Study II: Flow of Competencies in Tourism Management Courses

Amanda and Brian chose to note which courses aligned with the various Domains and performances directly into their evolving curriculum map.

|

Principle Category: General Business Operation Competency Outcome: Effectively manage a business by implementing organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives (MN1) |

|||

|

Task within management competency |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain I – Foundation (MN1-D1) |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain II – Application (MN1-D2) |

Assessment of task at Learning Domain III – Execution (MN1-D3) |

|

Organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives |

Identify components of successful vision, mission, and objectives Courses: 112, 171, 231, 252, 306 |

Plan operational objectives to meet the mission, goals, and objectives of the organization Courses: 219, 271, 306, 310, 312 |

Implement and critique organizational vision, mission, goals, and objectives Courses: 306, 310, 312, 499 |

Table 5: An advanced curriculum map for Tourism Management. In this map, course codes have been listed in association with each of the Domains. The leader’s coding system has also been added to the chart (MN1, and MN1-D1, MN1-D2, MN1-D3). This chart has been adapted from Metzler et al. (2017).

While elaborating on the initial map was helpful, Amanda and Brain also felt they needed to see the big picture. As they developed tables like the one above, repeating the process for all the competencies and outcomes of the program, it was getting complex, almost unwieldy. So, they mapped their curriculum using an alternative approach.

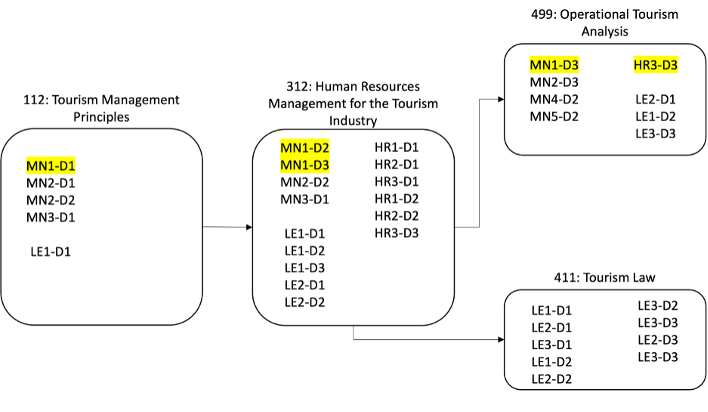

They developed a coding system to label outcomes and performances at each of the three Domains. For example, the above table became coded with MN1-D1, MN1-D2, and MN1-D3 for Management Outcome 1-Domain 1, -Domain 2, and -Domain 3. This coding approach enabled Amanda and Brian to develop the following sample flow chart in Figure 1 that offered them another view of their curriculum:

Figure 1: Sample Flow Chart for Tourism Management. This flow chart represents part of the curriculum – four courses (112: Tourism Management Principles, 312: Human Resources Management for the Tourism Industry, 499: Operational Tourism Analysis, and 411: Tourism Law). The codes marked in each of the boxes represent the various outcomes and domains associated with the course. Yellow highlighted text marks the coding that corresponds with Table X. For example, Course 112: Tourism Management Principles is associated with Management Outcome 1- Domain 1 (MN1-D1), identify components of successful vision, mission, and objectives. This flow chart has been adapted from Metzler et al. (2017).

Like Case I, these approaches to mapping enabled Amanda and Brian to develop the course-level curriculum for each of the courses in Tourism Management. Taken all together, they knew exactly which outcomes and which domains of performance were to be a part of each course in terms of the content, teaching, and assessment.

Case Study III: Course Planning for Germanic Studies

The next time the Germanic Studies team met, they focused on developing each of the courses they had mapped. Working in small, course-based teams, faculty member instructors (the subject matter experts) worked with an Educational Developer, Instructional Designer, Librarian, and Equity Advisor to:

- Write/Revise course learning outcomes based on the curriculum map. For example, the course outcomes for Course W were elaborated upon based on program outcomes of describing the values of one’s own culture and articulating the cultural perspectives of others. Writing outcomes at the course level meant contextualizing these overall performances for Course W specifically.

- Identify major forms of teaching and assessment that would address the program learning outcomes and level of performance previously mapped. If Course Z, for example, was to represent advanced forms of learning for two of the three program outcomes, what teaching and learning activities would shape the course in an online context? How would students demonstrate their advanced performance? Recall that Course Z was already taught in person. Leaders could therefore draw on the previous course structure to inform this conversation and consider how technology might be used to substitute, augment, modify, or redefine activities and assessments.

- Identify the availability and creative use of educational technologies that each course might utilize. The team knew they would be building courses in the institution’s learning management system (LMS) and the Instructional Designer was particularly well-versed in what LMS tools and technologies could be leveraged given the teaching and assessment strategies being devised.

Reviewing Existing Courses for Inclusion into a New Program

Case III highlighted the situation where previous courses exist, and program leaders have identified them for inclusion in the new program curriculum. This can be an effective and efficient way of drawing on established courses and curriculum in new program development. Here are some guiding questions to apply when drawing upon existing courses:

How does the course get mapped into the new program curriculum map? Where does it connect to program learning outcomes?

To what degree does the course align with the program? Are there elements about the course that do not relate to or align with the program?

Consider the situational factors of your program – your learners’ needs, the way the program will be offered – what adjustments, if any, will be needed of the existing course to work well for the program and its students?

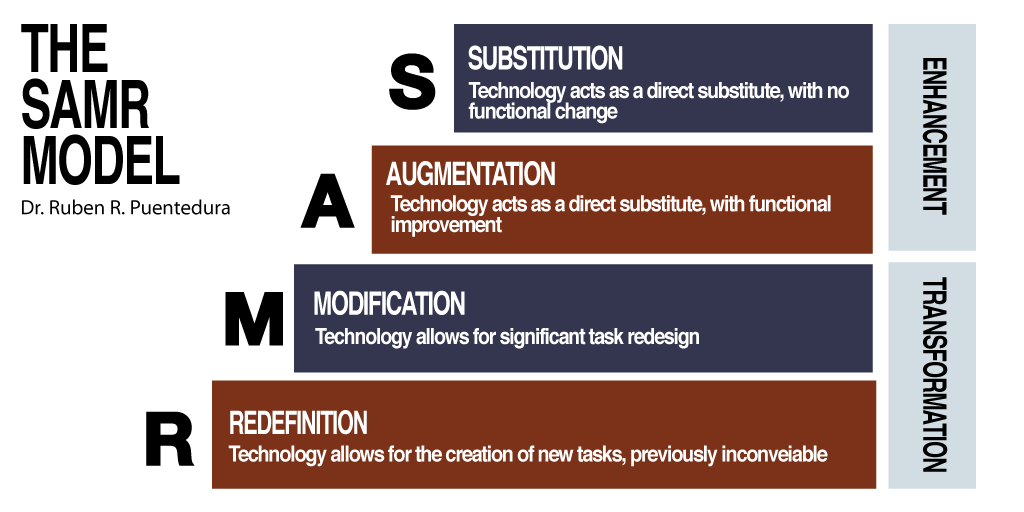

As existing courses are reviewed and adjusted for inclusion in the program, keep this adapted SAMR model in mind:

Originally developed by Dr. R. Puentedura to focus on the use of technology, the SAMR model is adapted here in application to course review.

Consider these questions:

- Does the course get incorporated into the new program by substituting it in as-is with no functional change?

- Are functional improvements required as the course is adjusted to the new program curriculum?

- Does the course require significant redesign for aligning it to the program and its situational factors?

- Are there ways of redefining the course itself, such that previously inconceivable ways of teaching and assessing student learning within that course are explored as it is incorporated into the program?

Overall Lessons from Cases

- Initial and draft curriculum maps are intended to capture general, high-level ideas of curriculum design. Mapping is an iterative process to return to again and again with different and deepening perspectives.

- As you develop your curriculum map, revisit identified frameworks, philosophies, or pedagogies identified in the curriculum vision phase to help guide the mapping process.

- Eventually, a curriculum map can help program leaders develop the course-level curriculum, that is, what will be taught and assessed, as well as which technologies will be utilized to support learning within the course.

Workbook Activity: Devise Your Own Draft Map

Try creating a draft curriculum map for yourself based on the Case examples you’ve seen so far. Remember, the goal is to capture broad, initial ideas for program structure rather than finer details of course specifics. Based on your interpretation of this as informed by your contextual factors, the level of specificity of your draft map will vary. You may be able to use this draft as a starting point for future conversations with your curriculum development team.

Unit Reflection and Resources

In this unit, you’ve:

- Considered the value of curriculum mapping as an approach to visualizing connections between the program/curriculum visions, program outcomes, and course plans

- Planned a curriculum mapping approach that will enable decision-making such as:

- What courses happen when and how in the program;

- What teaching and learning activities and major forms of assessment fit with each course in the program and why;

- And, what materials you will need to develop or source for each course you’re planning such as instructional content, teaching and learning activities, multimedia, assessment materials, rubrics, syllabi, and more.

Throughout the unit, you may have also found opportunities to:

- Reflect on the current state of course-level planning, design, and development

- Plan and initiate a team-based approach for curriculum mapping and course development arising from the mapping process

Actionable Tasks

In your Program Design and Implementation Workbook, consider the following questions next:

- Whose perspectives will be important in taking a team-based approach to curriculum mapping?

- What approaches will work best for continuing with curriculum mapping activities for program planning?

- When will you take action on curriculum mapping tasks?

- What obstacles do you anticipate in taking this approach? What might be some solutions or strategies for addressing these concerns?

Unit Resources

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- SOLO Taxonomy (Biggs & Collis, 1982)

- The ICE Model (Fostaty Young & Troop, 2022)