7 Community Organizing for People, Power and Change

Dr. Mahbub Hasan MSW, Ph.D.

Topic:

Topics:

- What is community organizing

- How community organizing works

- Identifying actors for Community organizing

- The Five Practices in Community Organizing

- People, Power and Change in community organizing

- Organizing Sentence

- Strategies for building relationships for community organizing

- Recruitment & Retention Best Practices

- The Snowflake Model

Introduction

This chapter focuses on defining community organizing, how it works, how to build relationships, and discusses practices in community organizing, including the Snowflake Model. This chapter also discusses how effective community organizing can create power and bring change in the lives of people. I participated in Community Organizing and Leadership training organized by Institute for Change Leaders and Toronto Metropolitan University. I have utilized learning from this training in my community work practice for the last six years and successfully organized community for various projects and campaigns. Therefore, in this chapter, I have used materials from the training manual titled “Building Skills for Change” written by Oliva Chow, who is a social justice advocate and educator.

1. What is Community Organizing

Community organizing refers to bringing community members together and providing them with the tools to help themselves or work towards common interests. It requires determination, perseverance, a clear plan with goals, reliability, follow-through, and a willingness to compromise (Citizen Committee for New York City).

Community work starts with community organizing. As community workers, we reach out to the community in good and challenging times. We start with listening to the community and acting together to strengthen relationships among its residents and members. We work together with the community to address their needs.

Community organizing is a process. The most critical step in community organizing is to inform and educate people on socio-political, economic, and environmental issues and encourage their participation in community development. Once people are aware of their issues and feel connected with their community, they will show their interest in the community development process, such as sharing stories, analyzing problems, developing actions, receiving training, and connecting with resources that help themselves and community members.

Video: What is Community Organizing

Source: YouTube, https://youtu.be/6ex6rN0hhm0

2. How community organizing works

A community worker engages with residents by telling stories about community issues and building relationships with other residents who experience the same issue. The Community worker develops a strategy that includes a vision, actions, and resources needed to address the problem. After the planning stage, the community worker will structure the team with specific roles and responsibilities. Someone may take leadership in raising funds, someone may be the lead for organizing and campaigning, and someone may lead advocacy efforts. After successful completion, the community worker starts a new process to address a similar or another community issue.

3. Identify Actors for Community organizing

Community organizing begins with stakeholder analysis/identification of actors. Who is out there we should know about? When developing an organizing strategy, there are five main groups to consider are: Constituency, Leadership, Supporters, Competitors, and Opposition (Chow):

Constituency/Core Participants: The people who are affected by the issue and should participate in your community initiative. People who interact or express interest with your group/marginalized affected group will be your constituency and your allies .

Leaders: These are the people who are actively working with you. This group is smaller than you think . Leaders are people will actively involve in the process and engaged in community organizing, fundraising, advocacy work.

Supporters: These people may have similar values or interests but are not yet contributing to your campaign/community initiative. Sponsors, funders, various community institutions, and associations can be a part of this group.

Competitors: They are the people doing the same or similar work as you. Either as a side project or a major project. They are influencing the discussions and activity around your issue.

Opposition: These are people who are actively working against community interests and your interests. They are the cause of your problem and may be blocking change.

4. The Five Practices in Community Organizing

Chow suggests that “Community organizing is all about people, power, and change – it starts with people and relationships, is focused on shifting power, and aims to create lasting change in the community” (, p. 10). The author suggested five key practices in community organizing are these are:

a) How to tell your story of why you want to organize for community change., why we must act, and what needs to be done soon.

b) How to build relationships with each other as the foundation of purposeful collective actions

c) How to structure relationships to distribute power and responsibility while fostering leadership development.

d) How to strategize to join forces with your people, turning your collective resources into the power to achieve clear goals.

e) How to enact your strategy into measurable, motivational, and effective action. Though organizing is not a linear process, organizers use the first three practices (stories, relationships, structure) to build power within a community.

Chow argues that last two practices i.e. strategy and action are about wielding that power to create change.

5. People, Power and Change in community organizing

People

People and their well-being are the heart of community work. If you strongly understand people, you will be a better change agent (Parada et al., 2012). Effective organizers put people, not issues, at the heart of their efforts (Chow). The organizer asks the first question, “Who are my people?” before asking “What is my issue?”

According to Chow, “Organizing is not about solving a community’s problems or advocating on its behalf. It is about enabling a group of people with shared values and common problems to mobilize their resources into action to solve their problems. (p.10). Chow also argues that identifying a community of people is just the first step and opines that “The job of a community worker is to transform a community – a group of people with shared values or interests – into a constituency – a community of people working together to realize a common purpose and make a change”. (p.10).

Power

Power is “…something a person or organization possesses and is willing to use. Power involves some sense of purpose or intention. We expect to meet some need or receive some benefits through the use of power” (Parada et al. p.90). Collaboration is one way those in power accomplish their objectives, and power sometimes implies resistance but can also be used in the spirit of cooperation (Parada et al. p.90).

Organizing focuses on power: who has it, who does not, and how to build enough of it to shift the power relationship and bring about change (Chow, p. 12). Reverend Martin Luther King described power as the ability to achieve purpose” and “the strength required to bring about social, political and economic change.” (Chow. p.12).

According to Chow, “Power is never given but needs to be seized.” The author also argued that “Transformative effects happen when people develop deep, trusting relationships with each other, and then share each other’s talents, which is essential for the success of our organizing efforts” (Chow, p.12)

Change

In organizing, change must be specific, concrete, and significant. Organizing is not about ‘raising awareness’ or speech making (Chow). The author suggests that

It is about specifying a clear goal and mobilizing your resources to achieve it. Indeed, if organizing is about enabling others to bring about change, and specifically, securing commitment from a group of people with shared interests to take action to further common goals, then it’s critical to define exactly what those goals are (Chow, p.13).

6. How to Develop Organizing Sentence

The “organizing sentence” is a tool to clarify the important components of your strategy and organizing plan. Every team in a campaign – including the core leadership team and each local leadership team – should write an organizing sentence unique to their team. Here is an example on how you can develop your key message for community organizing.

We are organizing (our people-who are affected by the issue) to (strategic goal-what change you together want to bring) through (tactics-actions) by (timeline-when).

For example, in a local neighbourhood, a core leadership team’s organizing sentence may look like this:

We, as a core team of 5 people, are organizing 350 tenants in our public housing building to identify everything that is broken and asking that they should be fixed in the building, through door-to-door and phone canvassing, meeting other buildings’ residents, forming a tenants association, staging rallies and pressuring local elected representatives and staging rallies by September 13, 2022.

7. Strategies for building relationships for community organizing

Community organizing enables people to turn their resources into the power they need to make the change they want (Chow). Power comes from our commitment to work together to achieve a common purpose, and commitment is developed through relationships. Chow suggested following steps for building relationships:

- The 1:1 meeting is a key tool for starting and maintaining relationships; there are three types of 1:1 meetings. 1) Recruitment (to find common purpose), 2) Maintenance (provide coaching and training), 3) Escalation (engage in actions based on skills).

- Relationships are rooted in shared values. We can identify values we share by learning each other’s stories and discussing decisive moments of our life journeys that shaped who we are. The key is asking each other, “why?” Why are you passionate about making a difference?

- Relationships are created by mutual commitment. An exchange becomes a relationship only when each party commits a portion of their most valuable resource, which is “time”

- Relationships involve consistent attention and work. When nurtured over time, relationships should motivate, inspire and become an important source of continual learning and development for the individuals and communities that make up your organizing campaigns

We have discussed more strategies in community engagement and outreach chapters.

8. Recruitment & Retention Best Practices

Chow suggested best practices for recruiting and retaining people for your community change work.

- Be open and enthusiastic: Organizing is an opportunity, not a favour. When asking for commitment, be enthusiastic.

- Always follow-up: When someone offers to get more involved, ask for their contact information and give them yours. Follow up with them as soon as possible, ideally within 48 hours.

- Always schedule for the next time: do not let anyone leave without asking when they will be coming back.

- Confirm commitment: use a hard ask and make sure your people understand that you are counting on them. Do not assume their commitment before they confirm it.

- Plan for no-shows: assume that half of your people will turn up. For example, if you need four people for a successful event, plan on scheduling eight.

- Design actions well: that is empowering to participate in

More strategies are discussed in our community engagement and outreach chapter.

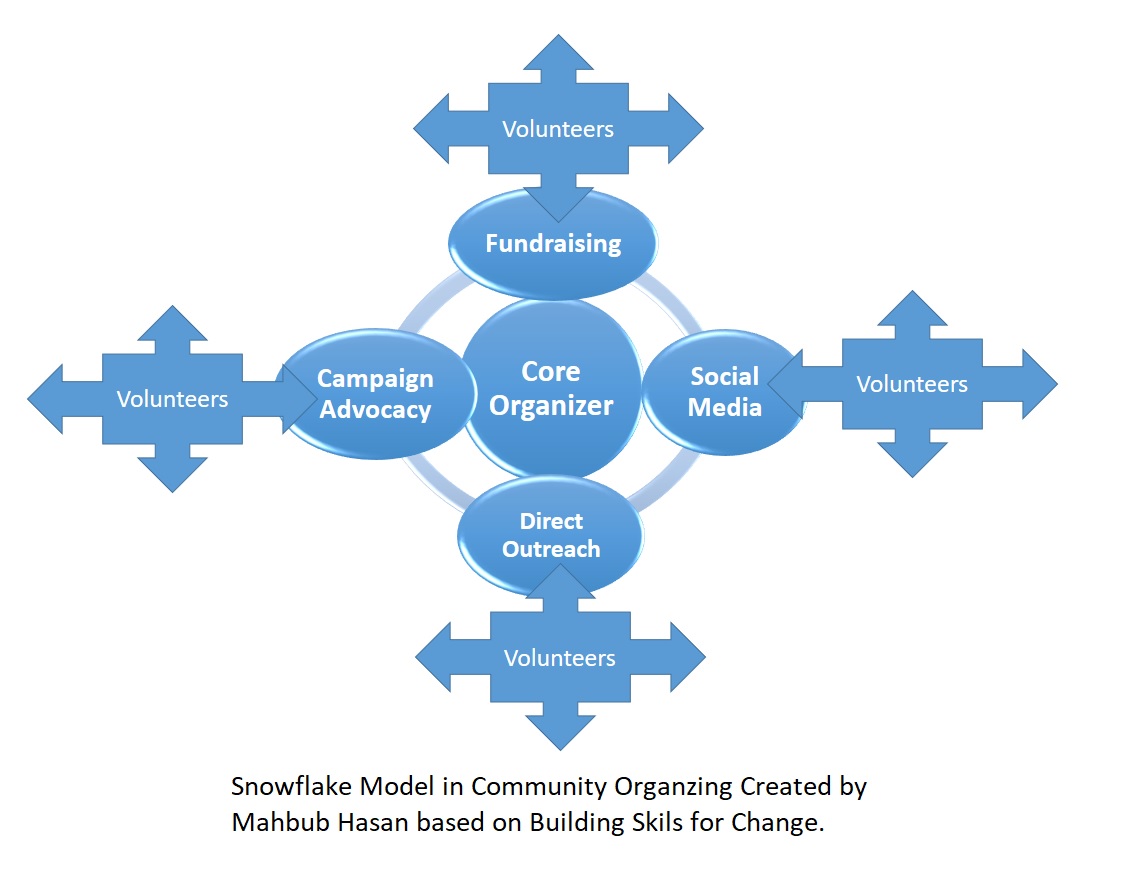

9. The Snowflake Model: A distributed approach to leadership and Community Organizing

The organizational model that best structures relationships to develop a community into a constituency is called the ‘snowflake model’ (Chow).

In the snowflake model, “leadership is distributed. No one person or group of people holds all the power; responsibility is shared in a sustainable way, and the structure aims to create mutual accountability/responsibility” (Chow, p. 11). The snowflake is made up of interconnected teams working together to further common goals

Key Takeaways and Feedback

We want to learn your key takeaways and feedback on this chapter.

Your participation is highly appreciated. It will help us to enhance the quality of Community Development Practice and connect with you to offer support. To write your feedback, please click on Your Feedback Matters.

Thank you!

References

Chow, O, (n.d). Building Skills for Change: Project organize (Version 4). The Institute for Change Leaders.

Davenport, C. (Eds.). (2005). Repression and Mobilization. Minnesota University Press.

Citizen Committee for New York City. (n.d) Basics of Community Organizing Neighborhood Leadership Institute Workshop. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f29763b60ad2b5398b30ae3/t/5f7cb4873787a67399e35798/1602008205160/Basics+of+Community+Organizing+Sep+19.pdf

Parada, H., Barnoff, L, Moffatt, K., & Homan, M. S. (2011). Promoting community change: Making it happen in the real world. (2nd Canadian Ed.). Toronto: Nelson Education Ltd