7 Midwifery Matters

Mary Renfrew, BSc, RN, RM, PhD, FRSE

This chapter will focus on the contribution that midwifery can make to the health and care of childbearing women, newborn infants , and families worldwide. It describes and defines midwifery, and summarizes the evidence on the impact of midwifery on survival, health and well-being. It identifies current data on important health outcomes, and presents a framework for understanding the different dimensions of the quality care that health systems should provide. The chapter also will examine why, when midwifery has been shown to be so fundamentally important, it is not already fully implemented in every country. Current global developments and challenges are outlined, and the need for strong advocacy for the development of midwifery is described. The chapter draws in large part on evidence published in The Lancet Series on Midwifery (1–4) and on a key WHO report. (5) More detail can be found in those documents.

3.1 Introduction

Midwifery matters for all childbearing women, their babies, and their families, wherever they live in the world, and whatever their circumstances. Evidence shows that skilled, knowledgeable and compassionate midwifery care reduces maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths, keeps mothers and babies safe, and promotes health and well-being. (1,2) In so doing, midwifery has a positive impact on the wider health system, and the economic sustainability of communities and countries. (3,4)

Midwifery achieves this impact by providing care for women and babies – all women and babies, both with and without complications – across the continuum from pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, labour and birth, and in the early weeks after birth. Good quality midwifery care offers a combination of prevention and support, early identification and swift treatment or referral of complications, respectful and compassionate care for women and their families at a formative time in their lives. Midwives work to strengthen women’s own capabilities and the normal processes of pregnancy, birth, postpartum, and breastfeeding (Table 3-1).

| Table 3-1. Definition of midwifery from The Lancet Series on Midwifery (1, p.1130) |

|

Midwifery is an essential part of any health system, and work to reform health systems will be strengthened by the implementation of good quality midwifery. (6) Working in partnership with other care providers – doctors, nurses, community and public health workers – midwives help to ensure that the woman, her baby and her family receive the right care at the right time. Even in settings where there are no midwives, or where midwives’ scope of practice is limited, women and babies need midwifery care. In these settings, care should be provided by others – whether doctors, nurses, community health workers, or others – who have essential training in midwifery skills. It is likely to be necessary in such situations for healthcare staff to work together to ensure that women and babies receive the full scope of care that they need.

The international definition of the midwife is shown in Table 3-2, demonstrating that anyone holding the title ‘midwife’ should meet the internationally-agreed standards for education and competence in practice.

| Table 3-2. International definition of the midwife (7, p.1) |

|

3.2 Maternal and Newborn Health and Care: Current Trends

3.2.1 Survival of Childbearing People and Newborns

Although pregnancy and birth are often straightforward and joyous events, complications for the woman, fetus, and newborn do occur, and can result in disability or death if appropriate care is not provided swiftly. Despite the worldwide gains in reducing maternal mortality in recent years, levels of mortality and morbidity for women and infants remain unacceptably high in many parts of the world with poor quality care being a major contributing factor. As a consequence the rights of childbearing women and infants to health and to life are severely compromised. (8,9)

The statistics that follow demonstrate the scale of the challenge to reduce stillbirths and maternal and newborn mortality. Behind these numbers lie the stories of the deaths of women and babies, each of which is a tragedy with a lasting impact on the partner, other children, grandparents, wider family and community. While the majority of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, preventable deaths also happen in high-income countries.

3.2.2 Maternal Deaths

Although there has been a decline of over 40% in maternal deaths since 1990, an estimated 303,000 women still die each year as a result of complications of pregnancy and childbirth, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. (10) Excessive blood loss, high blood pressure and overwhelming infection are responsible for more than half of these deaths, most of which are preventable. (11)

3.2.3 Newborn Deaths

Around 2.7 million babies die in the first 28 days after birth, accounting for 45% of all under-five-year-old deaths. (12) Almost one million of these deaths occur on the day of birth. By the end of the first week of life a total of nearly two million babies will have died. Again, most of these deaths are preventable. More than 80% of all newborn deaths and stillbirths result from the complications of prematurity (being born too early), complications during labour and birth such as birth asphyxia, and neonatal infections. Evidence is available on ways to prevent or treat these conditions.

3.2.4 Stillbirths

An estimated 2.6 million third trimester stillbirths occurred worldwide in 2015. Stillbirth rates have declined more slowly since 2000 than either maternal mortality or mortality in children under five. (13) The loss to mothers and families is profound, and the long-lasting grief can be compounded by shame and even a sense of failure.

Did You Know?

Although the majority of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, preventable deaths also happen in high-income countries.According to 2011 data from the US National Center for Health Statistics, when compared to seventeen other industrialized countries, the United States experienced the highest neonatal mortality rate at 4.04 per 1000 births. (14) Comparing maternal mortality rates between industrialized countries with over 300,000 births/year, the USA had the second highest rate of mortality with 16.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 births. (14)

Gene Declercq, PhD, created Birth by the Numbers, and summarizes these statistics in this video: https://youtu.be/a_GeKoCjUQM

3.2.2 The Health and Well-being of Childbearing Women & Infants

Essential as it is that lives be saved, it is also important that the huge majority of women and infants who survive childbirth have the appropriate care and support to enable a healthy and happy start to life.

Around 138 million women and 136 million infants survive childbirth. Of these, it is estimated that around 20 million women will experience acute and/or chronic clinical or psychological morbidity, such as incontinence, pain, and mental health problems, which can have a lasting effect on not only maternal but also infant physical and psychological health and well-being. (15) Additional burdens may result in the event of ongoing health care costs or an inability to work or inability to care for family members. (16)

A contributing factor to clinical and psychological morbidity is inappropriate use of interventions in childbirth, such as routine episiotomy, unnecessary cesarean births, which require the additional intervention of anesthetic procedures, and routine use of supplementary fluids for breastfed infants. Some health care systems have developed in a manner that focuses primarily on the identification of risk and the use of technological interventions. In such systems, interventions that are beneficial for women or babies with complications can be used routinely, resulting in those without complications being exposed to unnecessary and potentially harmful interventions. For example, lives can be saved by a cesarean birth when it is needed, but provide no benefit and potential harm to those who do not. The dangers of technological solutions becoming a key goal of the system, is demonstrated by the high rates of cesarean births in low- and middle-income countries, including Brazil (52% in 2010 (17)) and China (54-64% in 2008-2010 (18)), as well as by the high rate in the USA (32.8% in 2012). The consequence of a technology and intervention based approach is that the needs of pregnant women babies and families are not met and the opportunity to provide high-quality care is missed. There is also increasing concern about the sustainability of over-medicalized health systems.

A contributing factor to clinical and psychological morbidity is the inappropriate use of interventions in childbirth, such as routine episiotomy (a surgical incision of the perineum), unnecessary caesarean sections together with the necessary anesthetic procedures, and routine use of supplementary fluids for breastfed infants. Some health systems have developed to focus primarily on the identification of risk and the use of technological interventions. In such systems, interventions that are beneficial for some women and babies with complications can be used routinely, resulting in women and babies being exposed to the risk of potentially harmful interventions. It is not hard to understand that low- and middle-income countries looking for models of care to implement might be influenced by the apparent benefits of technological solutions. Lives can so obviously be saved by a caesarean section when it is needed. The dangers of technological solutions becoming the key goal of the system, however, are demonstrated by the escalating rates of caesarean section in Brazil (52% caesarean section rate in 2010 (17)) and China (54-64% caesarean section rate in 2008-2010 (18)), and by the escalating rates of interventions in the US. The consequence is that the needs of women, babies and families are not met and the opportunity to provide high quality care is missed, and there is increasing concern about the sustainability of over-medicalized health systems.

3.2.3 Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding makes a fundamentally important contribution to the health of the newborn and its development, as well as to the mother’s own health. (19) Breastfeeding rates are low in many countries, however. Despite the global recommendation that all babies should be exclusively breastfed until six months of age, the rate in low- and middle-income countries is only 37%. (19) Rates are even lower in high-income countries. (19) Breastfeeding rates, in common with many other indicators of health and well-being, are related to social inequalities.

External Link

The Lancet Series created a map of the global distribution of breastfeeding at 12 months, which you can view here:

http://www.thelancet.com/cms/attachment/2062646895/2065058658/gr1_lrg.jpg

A baby’s chances of being breastfed are affected by broad socio-economic and cultural trends; increasing urbanization, the marketing and availability of breastmilk substitutes, intergenerational patterns of feeding, and increasing employment rates for women in the absence of workplace and social support for breastfeeding, all have an influence. (20,21) The care and support that women receive from the health system can make a difference and can improve rates of breastfeeding. (22) This can include individual support by midwives and other health professionals, and by working to systematically remove harmful practices, such as routine supplementation with breast milk substitutes, limiting breastfeeding, and separating mothers and babies in hospital and community settings. The global effort mobilized under the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), also known as the Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI), was launched in 1991 by the World Health Organization (23) and UNICEF (24) with the aim of implementing practices that promote and support breastfeeding in all facilities providing maternity care and of removing harmful practices. There is an accredited programme that a maternity facility can take to support successful breastfeeding and be designated as baby-friendly. (24) The initiative has had a proven impact in increasing the likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life. One such example is Cuba, where 49 of the country’s 56 hospitals and maternity facilities have received the Baby-Friendly designation. Between 1990 and 1996 the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at four months of age nearly tripled from 25% to 72%. (24)

3.2.4 Longer Term Impact of Pregnancy & Birth

Birth is a very important stage in the journey of a child’s life, but what happens before and after birth will shape each child’s future. The first 1000 days of a child’s life – from conception to age two – are critical in the establishment of a foundation for longer-term health, development, and well-being. In that time, the child’s brain and nervous system are developing more rapidly than at any other time of life. The essential connections between physiology and psychology are being laid down; hormonal responses to stress and to both positive and negative feelings are learned.

In the early days, weeks and months of life the child will learn to form close and loving relationships, to develop confidence in his or her own abilities, to cope with adversity, and the essential skills of being a healthy and happy human being – or not, depending on the circumstances into which the child has been born. (25–27)

The short-term importance for the social and psychological well-being of mothers and their babies that results from receiving supportive high-quality care during pregnancy, birth and beyond is shown in newer research. However, there remains a paucity of longer-term population data on the social, emotional, developmental and mental health clinical outcomes. These longer-term outcomes are rarely measured or monitored, which places limits on our understanding of the impact of different systems of care. It is clear, however, that no matter the circumstances, the care and support provided through pregnancy, birth and postpartum plays an important role in the client’s ability to love and care for their child. (26)

While the importance of pregnancy, birth and beyond for the social and psychological well-being of babies and women is now better understood, population data on the prevalence of social, emotional, developmental and mental health outcomes is much harder to obtain than shorter-term clinical outcomes. These outcomes are rarely measured or monitored, which currently limits our understanding of the impact of different systems of care. What we do know, however, is that whatever the circumstances, the care and support of the mother through pregnancy, birth and after birth can play an important part in the mother’s ability to love and care for her child. (26)

Underlying some of these challenges is a disturbing problem of disrespect and even abuse of women and their partners/family members within the health care system. There are reports of being shouted at or scolded, abandoned when in need of care, being subject to discrimination, and having non-consented interventions. (28,29) Such treatment breaches professional standards and is a serious infringement of the human rights of childbearing women and their babies, and may stop women from seeking the care they need. These outcomes are not often measured, whether through routine data collection systems, or in specific surveys. Therefore, it is very difficult to know the prevalence of such incidents in different countries, and whether the situation is improving or worsening.

In summary, it is essential to know about the trends in key outcomes if students, practitioners and the profession of midwifery are to properly understand the needs of the clients, infants and families in their own and other settings. Comparing outcomes with other, similar settings, and monitoring changes across time is also important. As the Scottish physicist William Thomson Kelvin (1924-1907) said: “If you do not measure it, you cannot improve it.”

3.3 What do all Childbearing Women, Children and Families Need?

How can Midwifery Contribute?

The challenges we have just described inevitably raise important questions, such as: How do we improve the current situation? How can we consistently provide the compassionate, respectful care for women, babies and families that is so important at this vulnerable and formative time? How do we keep women and babies safe from harm? How should resources best be spent – on large hospitals, or on community services? How do we provide the right level of interventions such that they are available when needed but not overused? How do we make sure we reach all women and babies, and ensure that the most vulnerable are not excluded from access to good quality services? Who are the best caregivers for childbearing clients and newborn infants – midwives, obstetricians, nurses, or community health workers?

These are just some of the questions that health planners and health professionals must answer when planning services, deciding how to allocate resources, and managing the education of health professionals. These questions are fundamentally important, and sometimes contentious. People often have different opinions, and may argue that funds should be invested in one aspect over another. For instance, some may champion the needs of women, while others may focus on ill babies.

Evidence is essential to answer questions, but sometimes the evidence is not available in the form that we need, or not available at all. There are many randomized trials of treatments of complications, for example, but there are far fewer studies on how to prevent those complications happening in the first place. Very few studies have attempted to examine all the different aspects of quality needed to meet the needs of women and babies.

3.3.1 Quality Care for Women, Babies & Families – The Evidence-informed Framework

These questions were considered as part of the work of the global collaboration that developed The Lancet Series on Midwifery, the most far-reaching and high profile analysis of midwifery to date. (1–4) This work has been warmly welcomed by the international health care community, and is being used by national and global organizations to inform new strategic developments.

Did You Know?

The Lancet Series on Midwifery was developed collaboratively by an international, multidisciplinary group that included the input of researchers, advocates for women and children, clinicians from a range of disciplines, and policy-makers.

External Links

The Lancet Series on Midwifery has created the following YouTube videos to summarize the series and describe the framework for quality maternal and newborn care (QMNC):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjJ2zpgbF9A

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_s1TIt05Ycc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwdqjpPqzVk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pfskj_xbGE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UiXvtddT7r4

International responses to the series include this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RY-FBPjU9Vk

Early in the process, it was recognized that to examine the impact of midwifery, it needed to be measured against a gold standard quality of care, but that one did not exist. Previous studies had not examined all the evidence needed and had not conducted analyses in ways that could best answer some of the key questions. The authors of the Lancet Series on Midwifery had to start by agreeing to a set of core principles to guide the new analyses (Table 3-3).

| Table 3-3. Cores principles used in analyzing evidence in The Lancet Series on Midwifery |

|

The authors then combined different kinds of evidence – reviews of women’s own views and experiences, reviews of randomized controlled trials, and case studies – to identify all the elements needed by childbearing women, babies and families, wherever they live. Using this evidence, they built a framework to explain what was needed.

External Link

The following content discusses the visual found here: http://www.thelancet.com/cms/attachment/2021722654/2041538459/gr2_lrg.jpg

It was originally published as Figure 2 in: Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45.

First, the evidence showed that some practices were needed by all childbearing women and babies These are shown in the green boxes at the link above. They include three categories of practices:

- Education, information, health promotion

This category includes practices that predominantly enable women to make decisions and changes for themselves. Examples might include information about maternal nutrition, family planning services and breastfeeding promotion.

- Assessment, screening, and care planning

Examples in this category include planning for transfer to other services as needed, screening for sexually-transmitted diseases, diabetes, HIV, pre-eclampsia, assessing labour progress, and mental health problems.

- Promotion of normal processes, prevention of complications

Examples of practices in this category include prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, encouraging mobility in labour, clinical, emotional, and psychosocial care during uncomplicated labour and birth, immediate care of the newborn, skin-to-skin contact, and support for breastfeeding

The additional practices needed by women and babies with complications are shown in the orange boxes. These practices are important and can save lives and treat emergencies. The boxes are smaller than the previous ones not because they are less important, but to indicate that if good preventive and supportive care is in place, fewer women and babies should need these services. These additional services include:

- First-line management of complications

These practices include treatment of infections in pregnancy, anti-D administration in pregnancy for rhesus-negative women, external cephalic version for breech presentation, and basic and emergency obstetric and newborn care such as management of pre-eclampsia, postpartum iron deficiency anaemia, and postpartum haemorrhage.

- Medical, obstetric and neonatal services to manage serious complications

These practices include elective and emergency caesarean section, blood transfusion, care for women with multiple births and medical complications such as HIV and diabetes, and services for preterm, small for gestational age, and sick neonates.

There are additional practices needed for clients and babies with complications, which are important and can save lives and treat emergencies, but overall, fewer mothers and babies should need these services.

Next, the evidence showed that all childbearing women and babies – whether or not they have complications – need care to be organized to meet their needs (shown in purple). Maternal and newborn infant services need to be available, accessible, acceptable, and of good quality. (30) They need adequate resources, and for services to be provided by a competent workforce. Services must be integrated into the health system, work effectively across community and hospital services, and there must be continuity of care.

The evidence showed that care is more than what is done; how care is provided is just as important. The next category of the quality framework is about values (shown in blue). Women, babies and families need respectful care, good communication, and care that is tailored to their circumstances and needs – not a ‘one size fits all’ approach, or an approach that categorizes them into low- or high-risk. Women and families need good communication with the staff caring for them, and the staff must be aware of and understand the local circumstances in which they are living.

The next category is about the philosophy of care (shown in yellow). The evidence shows that women, babies and families need caregivers to work to strengthen their capabilities, not to undermine them by inappropriate interventions, or disempower them by over-medicalizing their care. Care should optimize women’s and babies’ own biological, psychological, social and cultural processes and not intervene too soon or unnecessarily.

Finally, the evidence shows that women and babies need care providers who combine clinical competence with interpersonal and cultural competence (shown in grey). Care providers need to work to their full capacity with a division of roles based on need, resources, and competencies. They also need to work in an environment where they themselves are supported within systems of professional education, regulation and employment.

This quality framework allows us to consider the contribution midwifery makes to care. It can be used to illustrate the scope of midwifery. It is clear from this chart that midwifery has vital contributions to make across all the dimensions of quality care, with the exception of the obstetric, neonatal and medical practices needed by women with complications (all except the rightmost orange box). Importantly, this evidence-informed framework demonstrates that women with complications still need midwifery care – it should not be withdrawn from them when medical care is provided. (1)

3.3.2 What Difference does Midwifery Make?

Using the evidence from over 450 Cochrane Reviews of effective care, The Lancet Series on Midwifery authors showed that if full scope midwifery is practiced, it can improve over 50 outcomes for women, babies, families and health services. These outcomes include saving lives, reducing harm, improving emotional well-being, mental health, and saving resources, as summarized in Table 3-4.

| Table 3-4. Outcomes improved by midwifery (1) |

|

The extensive impact of midwifery has important implications. No matter how a health system is organized, whether mothers and babies are in hospital, in the community, or at home, and whether they have complications or not, all women and all babies need midwifery care to provide information and support, prevent complications, and respond swiftly when complications develop. The Lancet Series on Midwifery summarized the evidence like this;

These findings support a system-level shift, from fragmented maternal and newborn care focused on identification and treatment of pathology, to skilled care for all, with preventive and supportive care, and treatment of pathology when needed through interdisciplinary teamwork and integration across facility and community settings. Midwifery is pivotal to this approach. (1, p.1130)

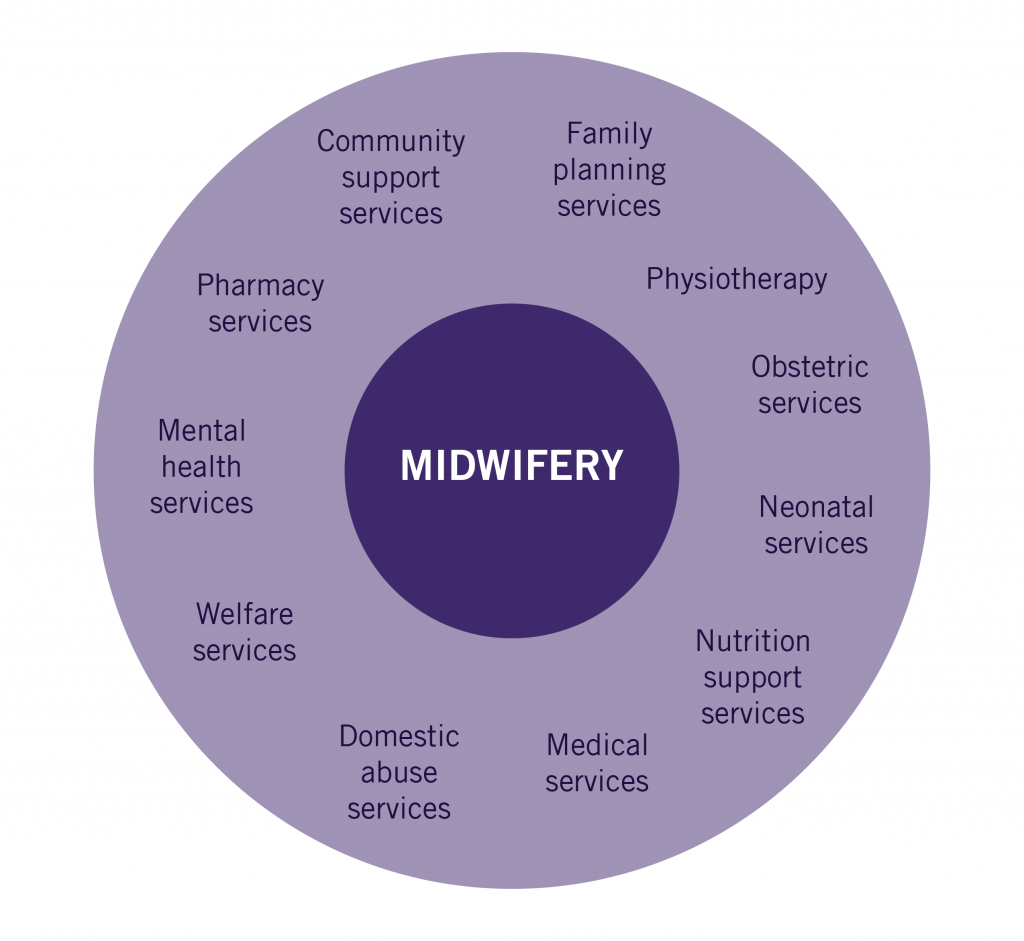

Interdisciplinary working is essential to providing high quality care. All the services that women and babies might need must work together to ensure that they are available, and in a timely manner. Indeed, midwifery not only works to support women and prevent complications, but also provides a central role in helping women to access other services, such as referral for obstetric or neonatal care, mental health services, or community support services (Figure 3-1). In the absence of high quality midwifery care it is likely to be more difficult for women to understand and access the services they need. Midwifery is a fundamentally important component of the interdisciplinary team helping to meet the individual needs of each woman and baby and to access all the services they might need.

Evidence demonstrates that midwifery – the combination of supportive, preventive, respectful, and compassionate care with swift response when complications arise – has been shown to improve a range of important outcomes; in essence it keeps clients and babies safe, both physically and emotionally. (1)

3.4 Why is Midwifery not Universally Available?

The evidence-based framework that we have just reviewed has shown that there is a vital role for midwifery in meeting the needs of women, babies and families wherever they are in the world. So, why is it not universally valued and available to all? History provides some clues to why this is the case.

Health systems across the world developed in different ways and for different reasons. In some countries, there are no midwives and care is provided by a combination of less-skilled workers with doctors to carry out emergency procedures. In others, doctors carry out much of the work of midwives. In some countries, there is strong and universal midwifery care. Each system of care has different outcomes. For example, systems that rely heavily on doctors tend to have higher rates of unnecessary interventions – sometimes referred to as over-medicalization – which can result in avoidable harm to childbearing people and babies, is wasteful of resources and is likely to be unsustainable over the long term.

Another challenge is the disconnect between evidence, policy, and practice. The evidence supporting the positive impact of midwifery is clear, but this is not necessarily reflected in policy decisions at the national or international level. As a consequence, resource decisions and the provision of care correspond to factors other than evidence, and women, babies, and families are deprived of evidence-based solutions.

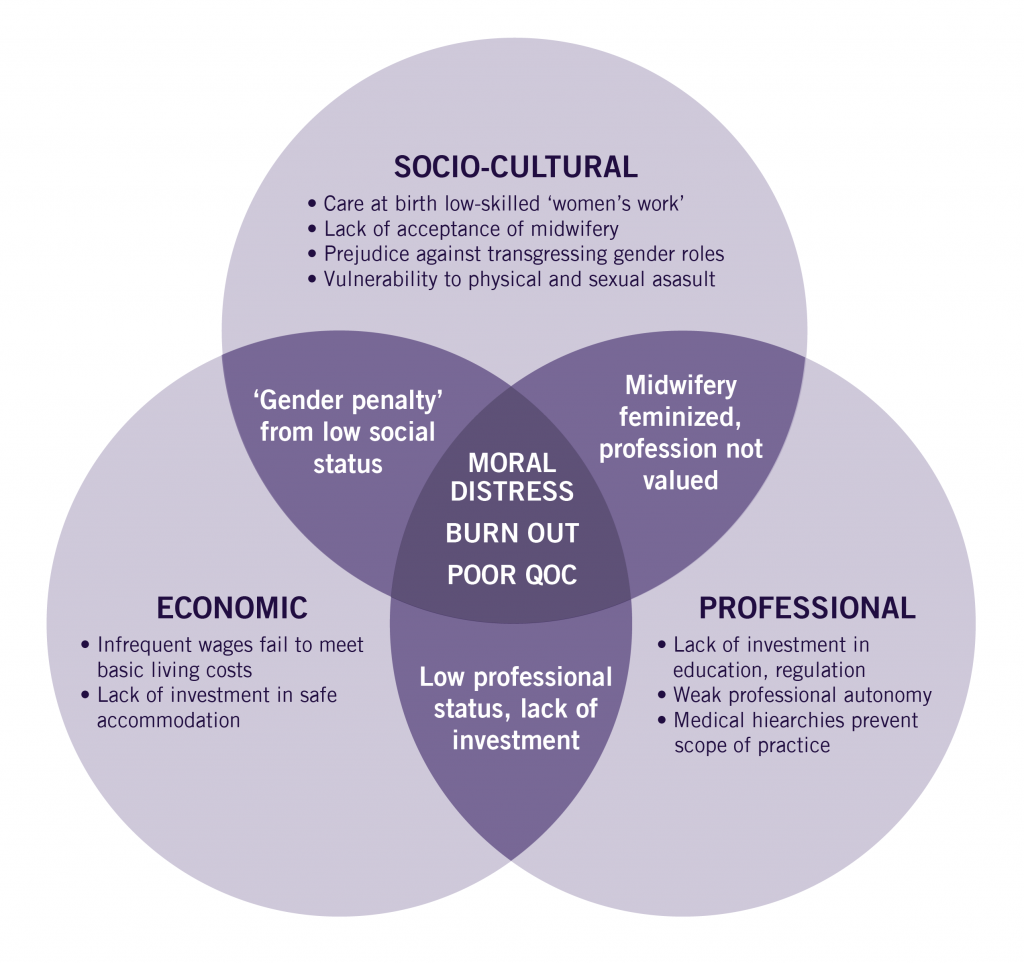

The root causes of the barriers to midwifery across the world were identified through literature reviews and by asking midwives about their experiences. (31) A summary of the identified interrelated factors appears in Figure 3-2. They found that socio-cultural, professional, and economic barriers combined to provide a hostile environment to midwifery in many countries. Low professional status and a low regard for midwifery resulted in difficult circumstances for midwives, and could lead to burn-out and distress. These factors were themselves set within the context of gender inequality. In many societies, not only were childbearing women subject to the low status accorded to all women but so too were the midwives, the majority of whom were women. This affected their working conditions and their relationships with interdisciplinary colleagues, and adversely affected their ability to provide evidence-based, high quality care.

New evidence about the positive contributions that midwifery can make to survival, health and well-being are prompting action by international agencies to promote midwifery. We are therefore at a crucial point in the evolution of the profession, globally; thoughtful, positive planning and co-ordination are needed to use this opportunity to gain the recognition and resources needed to scale-up the availability of high quality midwifery to make it accessible to all women and children, globally.

3.5 Midwifery in the Global Context

3.5.1 Advocating for Midwifery Availability

There are some key developments internationally that are helping to raise the profile of midwifery, and there is a new, growing awareness of its importance. These developments are about the health of mothers and children, and indeed, about health systems and economic development.

External Links

The following section discusses content found at the following links:

UN Sustainable Development Goals https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs

UN Every woman, every child http://www.everywomaneverychild.org

UN Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health 2015-2030

http://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org

WHO and UNICEF 2014 Every newborn: an action-plan to end preventable deaths

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/127938/1/9789241507448_eng.pdf?ua=1

Central to planning at international and country levels over the coming years are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Agreed by the UN in 2015, these 17 goals will influence strategy and action in all countries until 2030. (32) At first sight, the most relevant goal is Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. But on closer consideration, midwifery can have an impact across most of the other goals: improved nutrition, gender equality and empowering women and girls, reducing inequality, and increasing inclusivity, resilience, and sustainability. These are all goals that midwifery can contribute to achieving.

The growing understanding of the contribution midwifery makes has resulted in a strong movement, internationally, to promote and support midwifery. Organizations such as the World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund , the International Confederation of Midwives, the White Ribbon Alliance, and others, are collaborating to build a strong advocacy movement to tackle the barriers to universal provision of high quality midwifery care and to promote and support midwifery. (33)

This is an exciting time to be in the midwifery profession, as it is now being recognized as an important strategy to combat mortality, keep women and children safe, and contribute to sustaining health systems. It is an important profession, and your work in providing care and in advocating for women, children, and families will contribute to the growing global understanding that midwifery matters for all women and all children, in all countries.

3.6 Key Points Summary

- Midwifery is essential, for all women, babies, and families, everywhere.

- Midwives can play a critical role in promoting healthy practices for women and babies, from pre-pregnancy, through pregnancy to the first years of a baby’s life, but there are significant political, social, and economic challenges that have, thus far, prevented more widespread availability of high-quality midwifery care.

- This is an important time for midwifery – there are key opportunities including several global developments that promote midwifery , or to which midwifery can positively contribute.

References

- Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45.

- Homer CSE, Friberg IK, Dias MAB, Ten Hoope-Bender P, Sandall J, Speciale AM, et al. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. The Lancet. 2014. p. 1146–57.

- Van Lerberghe W, Matthews Z, Achadi E, Ancona C, Campbell J, Channon A, et al. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1215–25.

- Ten Hoope-Bender P, De Bernis L, Campbell J, Downe S, Fauveau V, Fogstad H, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1226–35.

- Midwives’ Voices, Midwives’ Realities Report 2016 [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250376/1/9789241510547-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Davidson PM. The Impact of Research Assessments on Midwifery. Midwifery. 2015;31(12):1119–20.

- International Confederation of Midwives Core Documents [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://internationalmidwives.org/knowledge-area/icm-publications/icm-core-documents.html

- Human Rights in Childbirth [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.humanrightsinchildbirth.org/

- A Rights-based Approach to Preventing Maternal Death and Injury [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/MaternalMortality.aspx

- Alkema L, Doris C, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2015;387(10017):462–74.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tun??alp ??zge, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2014;2(6).

- Neonatal Mortality [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/neonatal_text/en/

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, Amouzou A, Mathers C, Hogan D, et al. Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):587–603.

- Weiler J. Birth by the Numbers: The Update [Internet]. 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_GeKoCjUQM&feature=youtu.be&t=319

- Koblinsky M, Chowdhury ME, Moran A, Ronsmans C. Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: Neglected agenda in maternal health. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2012. p. 124–30.

- Storeng KT, Baggaley RF, Ganaba R, Ouattara F, Akoum MS, Filippi V. Paying the price: The cost and consequences of emergency obstetric care in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(3):545–57.

- Brasil Ministerio da Saude. As cesarianas no Brasil: situacao no ano de 2010, tendencias e perspectivas (Caesareans in Brazil: the situation in 2010, trends and perspectives). Brasilia; 2012.

- Feng XL, Xu L, Guo Y, Ronsmans C. Factors influencing Rising Caesarean Section Rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(1):30–9, 39A.

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet. 2016. p. 475–90.

- Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504.

- Baker J, Sanghvi T, Hajeebhoy N, Martin L, Lapping K. Using an evidence-based approach to design large-scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3 Suppl).

- Mcfadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, Buchanan P, Taylor JL, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017.

- Baby-friendly Hospital Initative [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/

- UNICEF in Action: The Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/baby.htm

- Leadsom A, Field F, Burstow P, Lucas C. The 1001 Critical Days: The Importance of the Conception to Age Two Period [Internet]. Available from: http://www.wavetrust.org/sites/default/files/reports/1001 Critical Days – The Importance of the Conception to Age Two Period Refreshed_0.pdf

- Entwistle FE. The Evidence and Rationale for the UNICEF UK Baby Frindly Initative Standards [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/09/baby_friendly_evidence_rationale.pdf

- Grille R. Parenting for a Peaceful World. Longueville Media; 2005.

- Freedman LP, Kruk ME. Disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: Challenging the global quality and accountability agendas. The Lancet. 2014. p. e42–4.

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth Report of a Landscape Analysis. Harvard Sch Public Heal Univ Res Co, LLC [Internet]. 2010;1–57. Available from: http://www.urc-chs.com/uploads/resourceFiles/Live/RespectfulCareatBirth9-20-101Final.pdf

- Social Council UE and. CESCR General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12) [Internet]. United Nations; 2000. Available from: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf

- Filby A, McConville F, Portela A. What prevents quality midwifery care? A systematic mapping of barriers in low and middle income countries from the provider perspective. PLoS One. 2016;11(5).

- UN. Sustainable development goals [Internet]. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. 2015 [cited 2017 Sep 19]. p. 1. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300

- Renfrew M. Optimising the contribution of midwifery to preventing stillbirths and improving the overall quality of care: Co-ordinated global action needed. Midwifery. 2016;35:99–101.

Long descriptions

A diagram listing the interdisciplinary services that midwifery can connect clients with: family planning services, physiotherapy, obstetric services, neonatal services, nutrition support services, medical services, domestic abuse services, welfare services, mental health services, pharmacy services, community support services. [Return to Figure 3-1]

A Venn diagram using 3 circles, arranged in a triangle (one circle at the top, two side-by-side below it). The circles are close enough that each circle overlaps with the other two, and all circles overlap in the middle.

The top circle is labeled ‘socio-cultural’, and contains the descriptions: care at birth low-skilled ‘women’s work’, lack of acceptance of midwifery, prejudice against transgressing gender roles, vulnerability to physical and sexual assault.

Moving down and to the right, the next circle is labeled ‘professional’ and contains the descriptions: lack of investment in education and regulation, weak professional autonomy, medical hierarchies prevent scope of practice.

Moving to the left, the third circle is labeled ‘economic’ and contains the descriptions: infrequent wages fail to meet basic living costs, lack of investment in safe accommodation.

Starting again from the top socio-cultural circle, it overlaps at the bottom right with the professional circle. In the overlap is the description: midwifery feminized, profession not valued.

The professional circle then also overlaps on its left side with the economic circle. In the overlap is the description: low professional status, lack of investment.

The economic circle then also overlaps at its top left with the socio-cultural circle. In the overlap is the description: gender penalty from low social status.

In the middle, all circles overlap, and it contains the description: moral distress, burn out, poor quality of care.[Return to Figure 3-2]