9 Health Education & Promotion

Mary Nolan, PhD MA BA RGN

This chapter provides a brief overview of the history of antenatal education for labour and birth. It considers the wider remit of parent education in the 21st century and discusses the principles of adult education with particular reference to leading effective groups for mothers, fathers and co-parents both in the antenatal and postnatal periods. Examples of many activities that midwives might employ to achieve important learning outcomes are given.

9.1 Role of the Midwife in Transition to Parenthood Education

The transition to parenthood period, from pregnancy to the first months of a new baby’s life, is an excellent time to promote the physical and mental health of the whole family because new parents have a particular openness to change at this stage of their lives. (1) Pregnancy and early parenthood offer a teachable moment in which people are exceptionally open to reflecting on their lives and aspirations, and prepared to make changes in order to be the best parent they can for their new baby. Midwives are uniquely placed to harness this energy for change of mothers- and fathers-to-be. Every encounter with a pregnant or new mother, or with a person who will be a key figure in the life of the new baby, is an opportunity for health education and for supporting their motivation to be ‘good enough’ for their babies.

Midwife-led transition to parenthood groups can be used to:

- Help parents-to-be to understand what happens in labour and birth

- Promote normal birth by increasing understanding of the benefits that normal birth confers on mother and baby

- Prepare parents to maximize the woman’s own resources for coping with the intensity of labour

- Boost parents’ knowledge and confidence to make their own choices in labour

- Increase parents’ knowledge of what new babies need in order to thrive

- Help parents devise personal strategies for achieving physical and mental wellbeing across the transition to parenthood

- Provide the opportunity to reflect on what kind of parent they’d like to be

- Enable parents to anticipate and prepare for some of the challenges that having a baby will present

- Help them to make friends who will support them after their babies are born

9.2 Key Figures in the History of Antenatal Education

In primitive communities (and in some communities today), girls learn(ed) the business of giving birth by observing and supporting their own mothers and relatives in labour. From an early age, they were primary carers for babies and infants in their families and villages. This meant that they came to maturity with an already well-developed set of skills for early parenting.

In the 20th century, in industrialized nations, birth began to move out of homes and into medical facilities, and traditional community structures began to disintegrate. This created the need for formal antenatal education to enable women and their partners to gain confidence and acquire skills for birth and parenthood. The agenda for antenatal education in the 20th century was determined by a number of key medical figures who made it their lives’ work to try to understand why human labour was so painful and what method of coping was best to help ease the pain. These pioneers of antenatal education include: Dick-Read, Lamaze and Bradley.

9.2.1 Grantly Dick-Read

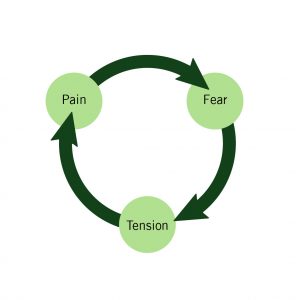

In his ground-breaking book, “Childbirth Without Fear” (2), Grantly Dick-Read (1890-1959) tells the story of how he attended the labour of an unsupported young woman in the East End of London (UK) who laboured without apparent distress and gave birth easily to her first child. The woman explained that she had not expected labour to be painful and Dick-Read deduced from this that it is culturally-induced fear of birth that leads to so many women having difficult labour experiences. Dick-Read proposed that fear of childbirth led to muscular tension which increased pain, thereby creating even greater fear (Figure 9-1).

His solution was to educate women about birth. By increasing their knowledge of what happens during labour, Dick-Read felt that women’s fear would be reduced. (2) In addition, he wanted to help women learn relaxation skills to use in labour so that they would be less tense and therefore, experience less pain and fear. He recommended that women should learn to recognise how their muscles feel when they are tensed and when relaxed, and described an activity that is often used in antenatal classes to the present day. This is an extract from his book:

Instruction is given in a quiet voice, slowly and clearly:

“Take a deep breath through an open mouth; curl up the toes and tense the muscles of one leg…(short pause)…release the breath slowly and relax the whole limb. Compare in your own mind the feelings of tension and relaxation.”

This exercise is repeated, followed by the other leg. The instruction is then extended to other groups of muscles allowing them to become alternately tense and relaxed. And so one works through the whole body, recognising the sensation of tension in a muscle and its absence in relaxation. (2, p.501)

Did You Know?

There are many non-physiological reasons that may contribute to the pain clients experience in labour. Nowadays, people often do not have any experience with labour prior to their own labouring, and anxiety about labour pain may lower their pain threshold. (3) Depending on the location of the birth and medical interventions used, labouring clients may be unable to adjust their birthing position, which may make managing pain difficult. In addition, media portrayal of birth is often sensational, depicting emergency situations rather than showing the normality of labour.

9.2.2 Fernand Lamaze

Fernand Lamaze (1891-1957), a French obstetrician, is associated with the psychoprophylactic method of childbirth preparation. Psychoprophylaxis was developed in the USSR in the 1930s and ‘40s as a method of managing labour without the use of pharmacological pain relief. Soviet obstetricians believed that pain in labour came from the mind rather than the body and that conscious relaxation, accompanied by controlled breathing, could alter women’s perception of pain (4) What might today be considered a viewpoint that is both patriarchal and flawed reflected the new interest in conditioned responses and behaviourism arising out of the work of Pavlov in Russia in the 1890s and Watson in the USA in the 1920s.

Lamaze visited the USSR to observe women using psychoprophylaxis for labour and birth and was inspired to introduce the method in France where it soon became popular. By the end of the 1950s, psychoprophylaxis was known across Europe, in the US, the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America. In 1956, Lamaze published his book, ‘Qu’est-ce que l’accouchement sans douleur? (‘What is childbirth without pain?’) (5) with an English translation appearing in 1958 under the title, ‘Painless Childbirth.’ (6) His classes included training in muscular relaxation and patterned breathing. Lamaze was also innovative in explaining medical terms in language that women could understand , enabling them to communicate more easily with maternity professionals.

Did You Know?

The theoretical base for psychoprophylaxis drew on the work of Ivan Pavlov, the Russian Nobel Prize winner, who demonstrated conditioned and non-conditioned responses to stimuli.

Did You Know?

There was great rivalry between Dick-Read and Lamaze. In ‘Painless Childbirth’, Lamaze scorns Dick-Read for not knowing enough about the workings of the human brain. Dick-Read was hostile to psychoprophylaxis because of its links with the Soviet system, which he detested, and also because he felt that his own work was not sufficiently acknowledged by Lamaze.

9.2.3 Robert Bradley

Robert Bradley (1917-1998) was influenced in his thinking by his upbringing on a farm where he regularly observed animals giving birth. He came to believe that, like animals, women could also give birth without drugs or distress. (Bradley’s belief that animals do not feel pain when birthing is questionable.) He challenged the then popular use of ‘twilight sleep’ for labour whereby women were confined to beds with high sides and so heavily sedated that they were unaware of the birth of their babies. Instead, Bradley developed a method of childbirth preparation that helped women draw on their own resources for managing the intensity of contractions. He taught abdominal breathing and deep relaxation and created birth environments which were quiet, dark and private. Bradley felt strongly that if a father had been shown how to support the mother in labour, he could make a significant contribution to her experiencing a straightforward vaginal birth. He therefore provided extensive education for fathers in his book ‘Husband-Coached Childbirth’ (7) In The Bradley Method, couples were, and are, taught different relaxation techniques that are practised throughout pregnancy so that mothers develop a conditioned relaxation response to their partner’s voice and touch.

9.3 Influential Childbirth Educators

9.3.1 Sheila Kitzinger

Sheila Kitzinger (1929-2015) was an English childbirth educator whose training in anthropology gave her insights into the different ways in which women the world over think about and approach labour and birth. A tireless advocate for natural childbirth, she rejected the didactic methods of antenatal education that were customary in the 1960s and ‘70s, preferring to provide antenatal sessions that offered women the chance to explore their fears and hopes around birth. ‘The Experience of Childbirth’ (1962) presented a pioneering account of the emotional and sexual dimensions of birth, and ‘The Good Birth Guide’ (1979) supported women to take control of birth at a time when medical intervention in labour was increasing. (8,9)

9.3.2 Andrea Robertson

A great friend of Kitzinger’s and a significant figure in the development of training for childbirth educators was the Australian birth activist, Andrea Robertson (1948-2015). As a practitioner, she supported the informed choice agenda by discussing with women and their partners a range of choices that they could make during labour, offering them alternatives to the interventions associated with the medical model of birth. She established a Graduate Diploma in Childbirth Education in Australia for health professionals who were keen to develop antenatal education services but whose initial training did not include preparation for facilitating groups of adult learners.

Did You Know?

Other influential childbirth educators include Marjorie Karmel (introduced the Lamaze method to the USA), Elizabeth Bing (co-founder of Lamaze International), Elizabeth Shearer (wrote and taught about having a vaginal birth after caesarean) and Penny Simkin (teaches about support in labour especially for women who have experienced a previous traumatic birth); Janet Balaskas (founder of the Active Birth Movement in the UK), and Jean Sutton (introduced the idea of ‘optimal foetal positioning’ – how a woman can assist her baby to assume the best position for a straightforward birth.

9.4 Contemporary Transition to Parenthood Education

The pioneer theorists and practitioners of antenatal education focused on preparing women and their partners for labour and birth. However, antenatal education has been reshaped and considerably extended in recent years so that it is now a curriculum for parenting education rather than just birth education. This is in response to the huge advances made by neuroscience in our understanding of early brain development, coupled with new insights from psychology into how social and emotional development are shaped by early relationships.

9.4.1 Stress & Relaxation

In recent decades, researchers in different countries began to realize that maternal stress in pregnancy impacted every aspect of the unborn baby’s development. Chronic stress could influence gestational age at birth, birthweight (10) fetal brain development (11) and the baby’s and young child’s physical, emotional and cognitive wellbeing (12) Stressful experiences in uterine and early life, and insensitive parenting could lead to a lifetime of adverse health and poor relationships. (13,14)

The first 1000 days (from conception to two years) appear to be crucial in determining the way in which stress is managed throughout life. Stress experienced in the womb, (mediated by maternal levels of adrenalin) and in the first years of life, appear to set children’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) thereby influencing their capacity for learning, and their capacity for learning, and their ability to regulate their emotions, handle frustration, and manage relationships in later years.

The midwife has an important opportunity in transition to parenthood groups, and during individual encounters, to help parents-to-be understand how stress affects them and thereby impacts on their babies and children, and to help them learn relaxation skills. Relaxation practice and discussion of the impact of stress on parenting are now central to parent education programs. (15) Relaxation is presented as important in pregnancy, as a strategy for coping with the intensity of labour and thereby increasing the likelihood of a normal birth, and as a means of managing parenting stress. A relaxation script for use with pregnant women and their birth companions can be found in the Appendix (‘A script for practising relaxation’).

9.4.2 Normal Birth

There is newly emerging understanding of the importance of vaginal birth in giving the baby the best possible start in life. Evidence now suggests that:

- The stress of labour is important for the release of prolactin, which contributes to the baby’s lung maturation (16)

- Elective cesarean may be a risk factor for childhood obesity (17)

- The use of synthetic oxytocin, such as Pitocin or Syntocinon®, during labour is responsible for decreasing breastfeeding rates (18)

There is a growing body of evidence on the importance of vaginal birth in seeding the microbiome of the baby, that is in facilitating the colonization of the gut with diverse bacteria acquired while the baby travels through the birth canal and comes into contact with bacteria in the mother’s vagina and fecal matter from her anus. (19)

Research has also found that in general, women feel more satisfied with a vaginal birth than a surgical one. (20) This is important because the relationship between the mother and baby is affected by the mother’s feelings about her labour. (21)

If the findings of research continue to indicate that cesarean birth is detrimental to human health, antenatal preparation for labour and birth will become increasingly critical in supporting clients and their birth companions to maximize their emotional and physical resources to achieve an uncomplicated vaginal birth.

9.4.3 Mental Health

Much is now known about depression during pregnancy as well as after the birth. What was once referred to as postpartum depression is in fact often a continuation of depression that started during pregnancy or is related to a previous history of depression . (22) Recognising and treating perinatal depression is a public health concern because it strongly impacts the relationship between the mother and baby which in turn scaffolds the new baby’s emotional and social development. (23) The contemporary agenda for transition to parenthood education therefore focuses on promoting the mental health of mothers across the transition to parenthood. There is also a need to consider the partner’s or co-parent’s mental health as the evidence is growing that if they are suffering from psychological impairment, this adversely affects the mother’s well-being and is linked to harsh parenting of their infants. (24, 25)

9.4.4 The Couple Relationship

The changes in roles, routines and responsibilities that mark the transition to parenthood can threaten the stability of even well-established couples. Couple conflict has been implicated in the development of emotional and behavioural problems in young children. (26) Transition to parenthood education provides an opportunity to help couples examine their relationship, understand how it might be affected by the arrival of their baby, recognize triggers for conflict, and develop strategies for quarrelling positively.

9.4.5 Sensitive Parenting

Early positive relationships form the basis of the child’s future wellbeing:

When we have secure attachment to loving others, we are granted a lifelong gift. When attachment processes are impaired, the diverse manifestations of psychic pain within the higher mental apparatus can lead to chronic feelings of distress throughout life. This distress often encumbers the way in which we can relate to others. (26, p. 345)

In every encounter with a pregnant or new mother, their partner, and their family, the midwife has a wonderful opportunity to promote sensitive, responsive parenting that helps the baby to become securely attached. Securely attached children are confident to explore the world as they grow up and demonstrate better understanding of others’ emotions, thereby enhancing their ability to form successful relationships. (28)

Did You Know?

Attachment theory was first developed by John Bowlby (1907-1990) who was a British child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. He worked with children with severe emotional and behavioural difficulties and this led him to propose the critical importance of early relationship experiences with key carers – parents, family members – for the later development of children’s personality.

9.4.6 Social Support

Many clients expecting their first baby may find themselves without a network of support once they leave work or because they live far from their extended family. Therefore, the traditional support and guidance provided by grandparents may not be easily accessible. Friendships made during parent education sessions support new parents’ mental health and enhance their self-efficacy as they give and gain reassurance that their babies are developing normally and that their parenting is satisfactory. By facilitating group formation, midwives can provide participants with a network to support them through the transition to parenthood. (15)

9.5 Developing a Transition to Parenthood Education Program

Pregnancy is an ideal time to explore the kind of birth that parents want to have and to help them acquire information and skills that will enable them to make and implement their own choices in labour. It is an opportunity to explain the importance of normal birth and to counter some of the common myths that parents are exposed to such as that cesarean birth has no adverse consequences for the baby and that formula milk is just as nutritious as breastmilk. It is also an opportunity to explore with parents what kind of parent they want to be; to increase their understanding of how babies develop self-esteem and resilience, and to explain how babies’ sense of who they are is shaped by the way in which the key people in their life respond (or don’t respond) to them (Table 9-1). Topics, such as bonding and attachment, baby cues, how babies communicate, how babies learn about themselves, language development, why babies cry and how to play with a baby, are now as central to the transition to parenthood education agenda as traditional topics, such as getting ready for labour and birth, bathing a baby, nappy changing, minor illnesses, feeding and safe sleeping (Table 9-2).

| Table 9-1. Characteristics of effective transitioning to parenting education (29) |

|

| Table 9-2. Topics for a transition to parenthood program | |

| Stress & relaxation | What hopes and fears do I/we have for the baby? |

| What factors affect the baby’s development in the womb? | |

| How will I/we recognize and manage my/our stress and the baby’s? | |

| What relaxation strategies can I/we use for pregnancy, labour and parenting? | |

| Normal birth | Where will the baby be born? How does labour start? What happens during labour and what will it be like? How do birth hormones work? Who do I/we want to be with me during labour? |

| How can I cope with pain? | |

| What can I do to help as the birth companion? Who will support me? |

|

| What will happen if the baby needs some help to be born? What is involved in induction, forceps, vacuum, cesarean? Do I/we have a choice? |

|

| How might I/we feel? | |

| How will I/we feel when the baby is born? What is birth like for the baby? What does the baby need once born? What happens if there’s a problem with the baby? |

|

| Mental health | How do I/we keep ourselves feeling positive in my/our everyday life? |

| How are everyday activities affected by the arrival of the baby? What things might make me/us unhappy after the birth of the baby? How can I/we recognize the signs of depression? What help is available? |

|

| Couple relationship | What kind of parent(s) do I/we want to be? How did my/our own parent(s) parent? How do we want to bring up the baby? How will we divide the household chores after the baby is born? How will we manage my/our household budget? How will we agree leisure arrangements? How do we settle arguments? What are good ways of managing conflict? How will our sex life be affected? |

| Sensitive parenting | What are the specific baby care skills I/we need to learn? |

| What does the baby need to grow into a confident, inquisitive, happy toddler? | |

| How can I/we play/interact with the baby? | |

| Why do babies cry? How should I/we respond to the baby when the baby cries? How can I/we build a close relationship with the baby whether breastfeeding or bottle feeding? How will I/we know if the baby is unwell? |

|

| Social support | What support do I/we need to be a contented parent? |

Did You Know?

A recent study has noted that there is ‘no compelling evidence to suggest that a single educational programme or delivery format (is) effective at a universal level’. (30, p. 118) In order to engage parents, it is vital to identify what they want to learn about and when, rather than present an agenda drawn up by the facilitator and delivered without reference to the particular needs or interests of the group members.

Reflect

What topics are covered in antenatal sessions/parenting groups at the place where you work?

9.5.1 Developing a Theory of Change

It is important when devising a transition to parenthood education program to be clear about the outcomes you hope to achieve and how you expect the program to achieve them. You need to have a theory of change or a logic model that summarizes the topics you cover in your sessions, makes clear how the parents will engage in the program and how what they do will lead to the desired outcomes. Table 9-3 provides an example of such a theory of change.

| Table 9-3. Theory of change linking topics, activities and outcomes of a transition to parenthood education program | ||

| CORE TOPICS | WHAT PARTICIPANTS DO | DESIRED OUTCOMES |

| How lifestyle factors, including stress, affect the unborn baby | Receive and share information about diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol, drugs, stress, etc. Practise relaxation techniques |

Healthy lifestyle choices |

| Labour and birth | Receive and share information about normal labour and birth, and about obstetric interventions Practise skills for communicating with health professionals and physical skills for coping with the intensity of contractions |

Better birth experience Improved parental mental health Increased normal birth rate |

| Babies’ physical, social, emotional and cognitive development | Receive and share information about babies’ cues and early development, including language development | Improved parent-infant relationships Better all-round development of the baby |

| Mindfulness/reflection | Group leader models reflection Parents have opportunities to develop mindfulness/reflective functioning |

More sensitive and responsive parenting Improved emotional wellbeing of the baby |

| The couple relationship | Group leader models good listening Parents practise listening and conflict resolution skills |

More sensitive and responsive parenting Improved emotional wellbeing of the baby |

| Mental health | Parents have multiple opportunities to talk to each other and to make new friends | Improved social support Decreased isolation of new parents Better mental health for parents and therefore, their babies |

| Stress management skills | Parents discuss their hopes and fears, identify stressors and practice stress management techniques for everyday use | Reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression Decreased use of health services |

| Where to go for help and information | Parents receive and share information about health, social care and voluntary sector services available to them | Decreased dependence on professionals Decreased isolation Optimum use of services available in the community |

While not every parent-to-be will feel comfortable attending a transition to parenthood group, many derive great benefit from being with people going through the same major life change as themselves. Research suggests that while parents value the factual knowledge and skills that they acquire in transition to parenthood sessions, they also value very highly the friendship of other group members (Table 9-4). (32)

| Table 9-4. Parent-perceived benefits of parent education | ||

| PERCEIVED BENEFITS | LEADING TO INCREASED | LEADING TO DECREASED |

|

|

|

9.6 Universal Transition to Parenthood Education vs. Targeted Education

The aim of all education and services offered to parents as they make the transition to parenthood is to promote a healthy pregnancy and normal birth, prevent maternal physical and mental illness, support healthy lifestyles and sensitive parenting, and to reduce families’ need for services by building the capacity of parents and communities to ensure the wellbeing of children. Parent education has been defined as ‘a process that involves the expansion of insights, understanding, and attitudes and the acquisition of knowledge and skills about the development of both parents and their children and the relationships between them’. (32, p. 18) In this endeavour, both universal and targeted services have value (Table 9-5). All families should receive support to help them improve their health and wellbeing, and there should be additional support for those who need extra help or who are most at risk.

| Table 9-5. Advantages of universal and targeted transition to parenthood education | |

| UNIVERSAL | TARGETED |

|

|

9.7 The Essential Elements of Leading Transition to Parenthood Sessions

9.7.1 Adopting a Strengths-based Approach

Adults, even if they are very young, always come to transition to parenthood sessions knowing something that is relevant to being a parent. They have all had multiple life-experiences that have shaped their ideas about parenting and what their baby will need. Some will have had a nurturing childhood and enjoyed the positive regard of their parents. Although these individuals have models of responsive parenting to draw on, this does not mean that parent education is wasted on them. Everyone needs time to think about the responsibilities they are undertaking, to voice their worries and receive reassurance and guidance if wanted and needed, and to build up a support network that will help them cope with the challenging early days, months and years of new parenthood.

Some people attending the sessions will not have had a childhood that set them up to be a sensitive parent. They may have experienced neglect; emotional, sexual or physical abuse; or inconsistent parenting that has left them anxious and uncertain about how best to parent their baby. Some may be suffering the disadvantages of poverty and/or ill-health; others who are at risk will not manifest any obvious need. Therefore, it is important to ensure that your approaches to facilitating transition to parenthood groups value everyone’s contribution and empower each person to recognize and build on their particular strengths.

Parent Education Activity – Recognizing and Valuing People’s Strengths as Parents

9.7.2 Avoiding Information Overload

There is little evidence that giving people information changes their behaviour. Change happens when people are motivated to change either because they recognize that their behaviour is having adverse effects on themselves or their loved ones, or because there is a financial or social inducement to change. Information is nonetheless important. However, it is not sufficient to just provide the information to the group members; they must be helped to understand the ways in which the information is relevant to their personal situation. Adults are pragmatic learners; they learn on a need-to-know basis. If the information you are giving them is deemed irrelevant, or not relevant at this particular point in their journey to parenthood, they are less likely to retain it. ‘The amount of correctly recalled information is closely related to the subjective importance of the material.’ (33, p. 220)

Many anxious educators talk too much and as a consequence they overwhelm their groups with facts, forgetting that people need little information but a great deal of emotional preparation in order to become confident and fulfilled parents. Additionally, giving information is less effective than sharing it, so it is important to invite participants to say what they already know about a particular topic and then give information that builds on what they have shared.

Parent Education Activity – Building on what Group Members Already Know: A Model for Information Sharing

9.7.3 Keeping groups small

Many, if not most, parents-to-be attend transition to parenthood programs in order to make friends, as well as to learn skills and acquire information that will help them meet the challenges of early parenthood. (15) The opportunity to make friends will be very much affected by the size of the group and the skills of the facilitator. A lecture delivered in a formal setting to a large group will not help those attending to get to know each other. The group has to be small enough to encourage participation and active learning. Anecdotal evidence from parent educators suggests that a group of between 8 and 16 people works best. However, many adults will not have the confidence to share their ideas even in a group of this size. The facilitator can therefore split the group into smaller groups of four to six and this will enable people who would be intimidated from speaking in the bigger group to take part in discussions and make friends.

Single sex small group work enables participants to share their thoughts and feelings that some would not share so readily, or at all, in a mixed group. A study on gender-specific group discussions found that when men are in an all-male group, they interrupt each other with supportive comments. (35) These supportive comments decrease as the number of female members in the group increases. (35) If there are same-sex couples in the group, the facilitator may decide not to do single sex small group work but this decision will depend on their knowledge of the group and what will work well for everyone in it.

The most important small group in transition to parenthood education consists of the childbearing client and their supporting partner. Transition to parenthood education provides participants with the opportunity to talk to the key people in their lives about the personal issues that will affect them deeply when they become a parent. For example, it seems that a major source of dispute between parents in the early weeks and months of a new baby’s life is quarrelling over who does what – how the daily chores and essential baby care tasks should be most efficiently and fairly shared out. In transition to parenthood sessions, midwives can give participants time to think about this together.

Parent Education Activity – Who Does What?

9.7.4 Providing Diverse Learning Opportunities

Everyone has a different way of learning; of receiving, sorting, processing, interacting with and applying information and skills. Everyone has a different way of understanding their feelings and opinions. The way in which you, as the group facilitator, learn most effectively, won’t necessarily be the way in which group members like to learn.

To ensure that everyone has a chance to learn in their preferred way(s), the facilitator needs to provide a variety of learning opportunities. Some people will find it most helpful to talk about their own experiences and listen to those of their peers. Others will find that visual aids, such as pictures and video clips, enhance their learning. Others again will enjoy kinetic or embodied learning, e.g. for coping with labour contractions or bathing a baby. Most learners will do best when classes include opportunities for multimodal learning.

9.7.4.1 Visual Learning

A well-chosen picture is likely to give rise to a series of relevant questions that group members would not have thought of without the visual stimulus. Pictures are particularly helpful to visual learners and the discussion that pictures often generate will be enjoyed by auditory learners. Modern technology facilitates opportunities for parent educators to provide lots of visual learning opportunities although it is important not to overuse or rely on PowerPoint® or YouTube™ clips, at the risk of alienating learners whose primary form of engagement is auditory or kinetic.

When selecting video clips, for example of birth or babies interacting with their parents, it is important to be mindful that the clip will impact each parent differently, and differently from the way that it impacts you as the facilitator. Some clips may enable understanding in one area while subverting key messages you are trying to get across in another . For example, a video clip showing the passage of the baby through the pelvis may contradict the work you are doing with the group around practising upright positions for labour and birth if the video shows the mother in a supine position. It is essential that you have the appropriate permissions from the intellectual property rights holder when using picture or video information.

Parent Education Activity – Helping Group Members Think about Support in Labour and the Physical Environment

9.7.4.2 Auditory Learning

In contrast to visual learners, auditory learners do best when they are able to hear information and then discuss it.

You can provide good learning opportunities for auditory learners by facilitating discussions, either in the whole group or in small groups. Many people will be too shy to contribute their ideas in a large group, even one that comprises only eight or ten people, and feel more confident to talk in a smaller group with just a few others. You can also enhance learning opportunities for auditory learners by providing verbal recaps.

Parent Education Activity – What Kind of Parent Do I Want to Be?

9.7.4.3 Kinetic Learning

The brain uses in excess of 20% of the body’s energy. (36) It also requires water, rest and protein to function efficiently. When a person sits down, their heart rate slows and the amount of oxygen that gets to their brain decreases by as much as 15%. (36) While parents sit in the group, their brains are therefore becoming increasingly inefficient. Simply standing up and moving around can increase the amount of oxygen getting to the brain, and so improve learning. (36) Movement is especially appreciated by kinetic learners.

There are many opportunities for kinetic learners in transition to parenthood sessions. Learning how to change a diaper or bath a baby requires practice. Just as it is impossible to learn to ride a bike by watching another person ride one, the only way to acquire any skills is to try them out and then keep practising! There is a long history in midwifery-led parent education of, for example, showing parents how to bath a baby by standing at the front of the group and demonstrating with a doll (or a baby). This was helpful to a point, but no new parent came away from this demonstration feeling confident about bathing their baby!

Parenting Education Activity – Bathing the Baby

Parenting Education Activity – Breathing through Contractions

Parenting Education Activity – A Script for Practising Relaxation

9.7.4.4 Using Role Play

Many educators are nervous of role play, and parents-to-be may also be reluctant to participate. However, handled sensitively – without ever mentioning the words ‘role play’ – it can be an immensely effective means of enhancing learning and understanding.

Parenting Education Activity – Cesarean Mock-Up

9.7.5 Ensuring a Satisfactory Pace of Learning

Most adults have a fairly short concentration span of about ten minutes. (37) Regular changes of activity will help to keep their attention so that they are learning for as much of the time as possible. People pay particular attention to the beginning and ending of a learning experience. (37) The first ten minutes of the session is a period of high concentration. Ice breaker activities that achieve the double goal of helping group participants get to know each other, and of covering a key issue, make the best use of this critical opening phase.

Parent Education Activity – Building Mental Health by Helping the Group Develop a Supportive Network (How to use Ice Breakers)

Similarly, to maximize on the opportunity provided by increased attention at the end of a session, the facilitator can offer a review of the topics that have been covered, and/or invite group members to share a ‘take-home message’. This will help group members retain key messages and ideas.

Parent Education Activity – Ensuring that New Learning is Retained so that it can be Drawn upon when Group Members Need It (Recap)

Since helping group members to build a supportive social network is one of the key aims of transition to parenthood education, it’s important to have a break during the session so that people can socialize over a cup of tea and/or light snacks. The educator should facilitate introductions between group members who are shy or uninterested in engaging with other group members.

9.7.6 Using Digital Tools

The majority of transition to parenthood education attendees today are what the American education consultant, Marc Prensky, describes as ‘digital natives’, i.e. people familiar from birth with learning through digital media. (38) There is a wealth of material on the web that can, with the appropriate intellectual property permissions, be used in transition to parenthood sessions to enable parents to learn in a way with which they are very comfortable.

Some useful videos are described below with a brief account of the keypoints which midwives and group participants could discuss.

9.7.6.1 Mother Talking to Her Baby

External Link

The following section discusses the video found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdLKpxktJB4

This video shows a mother lying on her side in bed talking to her very young baby who is lying next to her. The mother uses motherese and eye contact to engage with her baby. She ‘talks’ to her baby and then allows her to respond. When the baby pauses, the mother takes up the conversation. The baby is able to maintain excellent eye-contact and sustain the conversation for long periods. Occasionally, the baby turns away. This is her way of controlling the level of stimulation she is receiving. The mother in this clip is always respectful of her baby’s need for a pause. When the baby has had a rest, she returns to the conversation and the mother takes up her cue to continue. This is an example of a mother and baby who are perfectly attuned to each other.

This mother is helping her baby to develop emotionally as well as cognitively. As the baby watches her mother’s face (she is lying close to the mother so can see her clearly – babies are very short-sighted) she is learning not only about how to hold a conversation, but she is also linking what the mother is saying to the expressions on her face and to the tone of her voice. She is therefore having a lesson in human emotions as well as in human communication. Because the mother respects her baby and gives her baby space to express herself, the baby learns that she has a place in the world, and that her ideas are worthy of attention. This will enable her to grow into a healthy toddler who can assert herself, but also knows that other people have a part to play in her life as well.

The fact that this clip shows an interaction between a mother who is speaking a language with which group participants will probably not be familiar helps them to identify the characteristics of the exchange between mother and baby, focusing on how the mother/baby dyad communicate rather than on what they are saying.

9.7.6.2 The Importance of Reading to Babies

Storytime routines benefit even the youngest children, helping them to build vocabulary and communication skills critical for school readiness (39) It is never too soon to start reading to a baby. The primary aim of reading to a tiny baby is not to teach them to read; rather, reading is an opportunity for the parent to hold their baby close, thereby stimulating the release of oxytocin, which is the hormone of social bonding, thereby enhancing parent-child relationships; to have a conversation with their baby, and to help the baby develop a sense of ‘story’ and of sequence – beginnings, middles and ending – all of which lay the groundwork for the infant mind to acquire early language and literacy skills.

The best books for babies and very young children are picture books that enable a story to be told but offer the flexibility to link images and ideas to the baby’s environment. The speed with which babies and toddlers come to understand how a book ‘works’ is amazing. They quickly learn about page turning, naming objects in pictures and appreciating that books have a start and a finish.

External Link

The following discusses the video found here: https://www.youtube.com/embed/FJUxDt93X5s?feature=player_detailpage

The baby in this video is just able to sit up (probably about seven or eight months old), yet she is able to mimic the rhythms of the story she has probably been read many times; she concentrates on the page and signals that she has reached ‘the end’ of the story by turning to the adult in the room for acknowledgement. This baby has already developed an enjoyment of books and of ‘reading’ that will stand her in good stead when the moment comes for her to learn to read in some years’ time.

9.7.6.3 The ‘Still Face’ Experiment

External Link

The following section discusses the video found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=apzXGEbZht0

This video clip shows the famous ‘still face’ experiment devised by Professor Edward Tronick at the University of Massachusetts in the 1970s. A mother is invited to interact with her baby who sits opposite her in a high chair. After a few moments during which the baby is fully engaged, the mother is asked to turn away and then return to look at her baby with a totally blank face. The baby is immediately taken aback and puzzled. As the mother continues to be non-responsive, the baby tries increasingly desperately to attract her attention and get her to re-engage in their playtime. The baby’s vivacity quickly turns to wariness and finally, she starts to flail her arms and legs and cry, looking away from the mother and withdrawing from engagement with her.

This clip illustrates firstly, a positive interaction between a mother and her baby, with each clearly enjoying the other’s company. After the mother adopts the ‘still face’, the clip shows how diverse the methods are which the baby uses to try to get her to re-engage. Having a relationship with the key adult in her life is vital for her wellbeing and she strives to ensure the continuity of that relationship. At the end of the clip, the baby demonstrates the kind of behaviour that infants who have not received sensitive, responsive parenting will manifest – withdrawing, crying (but ultimately becoming silent) losing motor control and sending out stress signals.

9.7.6.4 How Babies Take the Lead in Shaping Encounters with Others

External Link

The following section discusses the video found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N9oxmRT2YWw

This is a very funny clip that shows a young baby’s response to a new experience – his mother energetically blowing her nose close to him. The baby demonstrates alarm, but doesn’t cry, suggesting that he has a secure relationship with his mother and knows that she is to be trusted even when she does frightening things. When the mother blows her nose again, the gap between her action and the baby laughing is much shorter than the first time, indicating that the baby has learned that this behaviour is not threatening. Soon the baby is leaning forward in his chair, watching the mother intently, clearly encouraging her to ‘play the game’ again and the mother willingly responds to his cues although her nose is becoming rather dry! Encouraged by her baby’s evident enjoyment, she talks to him, thereby adding a new element to the interaction between them. At the end of the clip, the baby startles again in response to the mother’s action, momentarily losing control of his arms and flailing, but very quickly recovers and laughs joyously. This baby understands that laughter is a positive form of human communication and can be used to encourage further interaction.

9.7.6.5 Text Messaging

There is a body of evidence, drawn primarily from smoking cessation studies and HIV research, to suggest that the use of texting to transmit key information may be very effective in promoting healthy lifestyles and improving outcomes for patients with various conditions. (40–43) It would seem reasonable to assume that text messages could also be used to reiterate important information shared during transition to parenthood sessions and support and encourage people in their aim to be sensitive parents.

In British Columbia, a telephone text-messaging service called SmartMom (44) has been developed to deliver prenatal education. SmartMom texts users three messages each gestational week, providing evidence-based information. Messages are consistent with current professional guidelines and peer reviewed prenatal education curricula, and have been designed to facilitate clients’ access to knowledge and local resources, to understand prenatal assessments, and to promote behaviour change to support healthy pregnancy and delivery.

External Link

Learn more about the SmartMom text messaging program here: https://www.smartmomcanada.ca/index.aspx

In order for messages to be effective, the research to date suggests that they should be:

- Empathetic – Acknowledging that behaviour change is difficult and encouraging clients to do the best they can (for instance, with regards to quitting smoking) rather than threatening them with adverse outcomes if they don’t. (45)

- Personal – Tailored to the individual needs and interests of the user

- Motivational – e.g. “Keep going, you can do it!”

- Goal-setting – Goal-specific and time-limited.

- Regular (reliable) – Erratic use of messaging doesn’t have the impact that regular messaging, such as once a week, has on maintaining motivation and knowledge levels.

9.8 Parenthood Education for Non-Childbearing Partners

Early editions of Myles’ Textbook for Midwives, known for decades the world over as ‘the midwives’ bible’ presumed that antenatal classes would be attended by pregnant women only. In the 1964 edition of her book, chapter 41 is entitled ‘Mothercraft Teaching by Midwives’ and is 73 pages long.(46) Towards the end, there is a single paragraph headed ‘A Word to the Expectant Father’. Fathers are assumed not to be participants in antenatal education even though Myles observes that ‘during this century (the 20th) men have been taking an increasing interest in the subject of child-bearing and rearing’ (p727). Myles also assumes that all women attending ‘mothercraft’ sessions are married and that a family consists of mother, father and child(ren).

The situation is, of course, very different today when a variety of family structures are socially accepted and babies may not be being born into traditional nuclear families. Same-sex couples are now seeking transition to parenthood education as are couples where one partner is an experienced parent and the other is becoming a parent for the first time. Individuals and couples who are going to adopt a baby come to sessions; young mothers may come with their own mother; men may come who are not the biological father of the unborn baby. Pregnant women may attend with a female or male friend who is going to be their birth companion.

The challenge and excitement for the facilitator of leading such varied groups is to ensure that everyone is made welcome; everyone has the opportunity to acquire the information and skills they are seeking, and to share their particular feelings about becoming a parent or co-parent.

9.8.1 Including Fathers

Today, there is far greater understanding of the powerful influence exercised by fathers over a range of outcomes for their children. Researchers have identified the significant role that fathers play in determining the success of breastfeeding (47,48) and have recommended that efforts be made to ensure that fathers are well educated about infant feeding, and general healthcare issues related to babies and infants. (49) Paternal disengagement from their babies is predictive of early social problems in children, while fathers playing with their infants correlates with a reduction in behavioural problems in boys and emotional difficulties in girls. (50)

Given the evidence that fathers can play an important part in the healthy development of their infant, it is important that midwives offer them specific support across the transition to parenthood. Men need to develop their identity as fathers as soon as possible and find a positive role for themselves in the new family. (51) Engaging with father during pregnancy and providing education about early child development and babycare skills ensures that ‘paternal caregiving patterns that develop during infancy persist and influence the way in which fathers interact with their children over time.’ (52)

9.8.2 Including Non-birth Mothers

All members of the LGBTQ2 community should feel welcome at transition to parenthood sessions, and facilitators need to ensure that teaching and learning activities always include non-birthing parents.

Facilitators may become very anxious about not using the ‘correct’ language to refer to people’s relationships and thereby causing offence. At a time when LGBTQ2 parents are struggling to gain recognition and there is not enough research on their needs in parenting education, the issue of language naturally assumes a particular sensitivity. Yet even parents who identify as gay recognise that they, too, can still make mistakes with language. The authors of a very recent book entitled ‘Pride and Joy: A Guide for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans Parents’ (53) write in a section headed ‘A word about words’:

We recognize that both ‘LGBT’ and ‘straight’ cover a huge variety of different family shapes and self-definitions…We are also aware that language is powerful, and for times where our language inadvertently denies experiences or leaves a reader feeling silenced, we apologize unreservedly. (p11)

Remember that whatever group members’ gender, sexuality, partnership or parenting status, they are attending the transition to parenthood sessions to try to become the best parents they can, and to learn from the facilitator and from the other group members. Provided the facilitator is kind, respectful, an excellent listener, and a skilful group leader, there will be few, if any, parents who complain should s/he use an ‘incorrect’ title, word, or phrase.

9.9 Evaluating Transition to Parenthood Programs

One basic indicator of the success of a transition to parenthood program is the number of parents-to-be attending each week. If the number remains steady from the first session to the last, and people who can’t attend contact the facilitator to say why they can’t come and express regret, this is an excellent indication that the sessions are being enjoyed by the parents. And there is little learning without enjoyment! One aspect of the facilitator’s public health role is to enthuse the parents-to be with a desire to learn more. Some of those attending sessions will have had unhappy experiences at school and may have become disenchanted with education, associating it with feelings of inadequacy or humiliation. If the facilitator can provide a truly engaging and relevant experience of education, this may play a part in encouraging parents-to-be to continue to learn as they raise their children, which may in turn transmit a love of learning to their children.

As a facilitator, you need to be observing your group closely to gage how effective the session seems to be in enabling learning. Indications that group members are learning include:

- Making links between information being shared in this session and information from previous sessions, thereby demonstrating that they are expanding their knowledge-base and applying it

- Asking insightful and challenging questions that demonstrate understanding of the ideas and concepts being explored

- Able to demonstrate practical skills without support

- Making statements indicating a shift in their values or motivations (e.g. ‘I used to think that … but now I see that ….’)

- Arranging to meet outside the session (i.e. taking an interest in each other’s lives and building social networks)

While it is satisfying to have an indication that the people who attended the session enjoyed it, this is not sufficient; there must be a more robust evaluation to gauge how much the group members have learned. Learning happens in three domains:

- Cognitive: This is about acquiring accurate factual information, understanding it and being able to apply it to one’s personal circumstances.

- Affective: This means becoming more aware of one’s own ideas, prejudices and feelings, with the result that one’s attitudes and behaviours change.

- Motor: This is about learning skills that require bodily actions and expressive movements.

9.10 Learning Outcomes

Each session should be designed with learning outcomes in mind and the content designed to achieve the desired outcome (Table 9-6).

| Table 9-6. Examples of learning outcomes | |

| By the end of this transition to parenthood session, participants will be able to…… | Describe what they can do to help their newborn adjust to life outside the womb (cognitive) |

| Bath a baby (motor) | |

| Explain the terms: cervix, show, uterus, first/second/third stage, placenta (cognitive) | |

| Talk about how they feel household chores should be divided between the couple after their baby is born (affective) | |

| Understand their options for labour and birth and describe their personal preferences (affective) | |

| Hold a baby of less than three months in a good position to talk to them (motor) | |

Reflect

Look at the agenda for any transition to parenthood or antenatal education session you have observed and decide what the learning outcomes might have been. Do you feel they were achieved? What evidence do you have that they were or were not?

Once the group members have left, you should go through each of your intended learning outcomes and ask yourself whether they were achieved during the session. This is a rigorous process, requiring evidence from the session that learning took place. If the outcome of your evaluation indicates that one or more learning outcomes were not achieved, your agenda for the next session should include further opportunities to achieve those outcomes.

The impact of a transition to parenthood program can be further evaluated by arranging a reunion for the people who attended it some weeks after their babies have been born and ask them what impact the program has had on their experience of labour, birth and early parenting, including which components were relevant and which were not. Such a reunion is also an opportunity for the new parents to debrief their labours, swap stories, see each other’s babies, and renew friendships made during the program.

9.11 Reflection

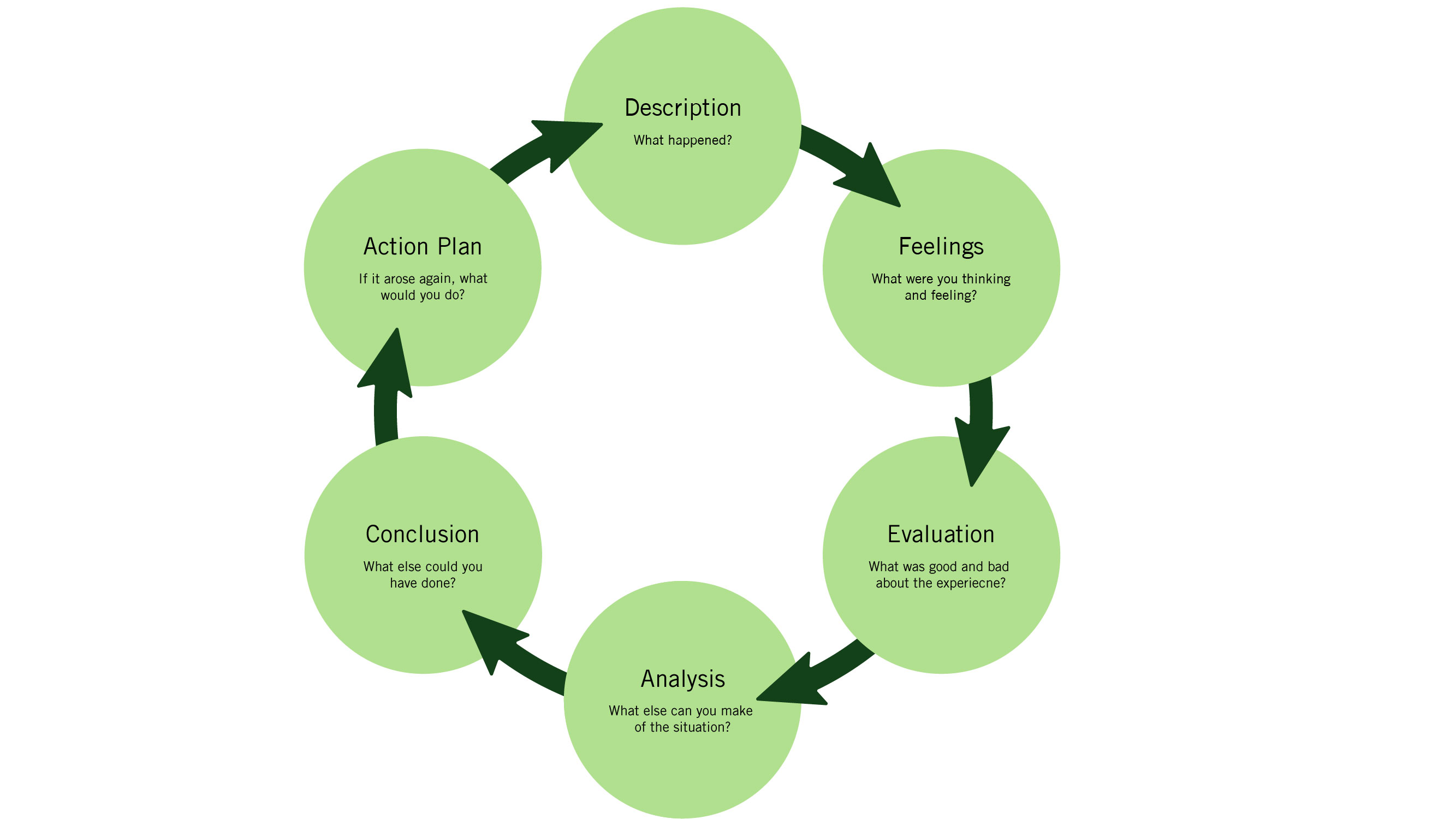

Given that transition to parenthood education offers a profound opportunity to make a difference to the lives of babies and children by promoting sensitive, responsive parenting, the facilitator has a responsibility to reflect on every session. Gibbs’ reflective cycle (Figure 9-2) can be used to explore individual incidents occurring during a transition to parenthood session, or to reflect on the session as a whole.

Reflection – Transition to Parenting Session

References

- Halford WK, Markman HJ, Kline GH, Stanley SM. Best practice in couple relationship education. J Marital Fam Ther [Internet]. 2003;29(3):385–406. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12870411

- Dick-Read G. Childbirth Without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth. New York: Harper & Bros; 1944.

- Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: Divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84(1):65–75.

- Michaels PA. Lamaze: An Internation History. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Lamaze F. Qu’est-ce que l’accouchement sans douleur? H. Regnery Co.; 1956. 192 p.

- Lamaze F. Painless childbirth: Pyschoprophylactic method. London: Burke; 1958. 192 p.

- Bradley RA, Hathaway M, Hatahway J, Hathaway J. Husband-Coached Childbirth. New York: Bantam Books; 2008.

- Kitzinger S. The Experience of Childbirth. 5th ed. Penguin Books; 1987. 300 p.

- Kitzinger S. The Good Birth Guide. London: Harper Collins; 1979. 475 p.

- Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Garite TJ. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(4):858–65.

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Beveridge M, Glover V. Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180(JUNE):502–8.

- Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: How and why? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2007. p. 245–61.

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):693–710.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58.

- Nolan ML, Mason V, Snow S, Messenger W, Catling J, Upton P. Making friends at antenatal classes: a qualitative exploration of friendship across the transition to motherhood. J Perinat Educ [Internet]. 2012;21(3):178–85. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3392600&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

- Hauth JC, Parker CR, MacDonald PC, Porter JC, Johnston JM. A role of fetal prolactin in lung maturation. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 1978 Jan [cited 2017 Jul 28];51(1):81–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/201892

- Hermansson H, Hoppu U, Isolauri E. Elective caesarean section is associated with low adiponectin levels in cord blood. Neonatology. 2014;105(3):172–4.

- Bell AF, White-Traut R, Rankin K. Fetal exposure to synthetic oxytocin and the relationship with prefeeding cues within one hour postbirth. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(3):137–43.

- Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, Grigoryan Z, Dominguez-Bello MG. The infant microbiome development: Mom matters. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2015. p. 109–17.

- Dunn EA, O’Herlihy C. Comparison of maternal satisfaction following vaginal delivery after caesarean section and caesarean section after previous vaginal delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):56–60.

- Rowe-Murray HJ, Fisher JRW. Operative intervention in delivery is associated with compromised early mother-infant interaction. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;108(10):1068–75.

- Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:24.

- Peper M, Markowitsch HJ. Pioneers of affective neuroscience and early concepts of the emotional brain. J Hist Neurosci [Internet]. 2001;10(1):58–66. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11446264

- Luoma I, Puura K, Mäntymaa M, Latva R, Salmelin R, Tamminen T. Fathers’ postnatal depressive and anxiety symptoms: an exploration of links with paternal, maternal, infant and family factors. Nord J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2013;67(6):407–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23286693

- Rodriguez ML, Dumont K, Mitchell-Herzfeld SD, Walden NJ, Greene R. Effects of Healthy Families New York on the promotion of maternal parenting competencies and the prevention of harsh parenting. Child Abus Negl. 2010;34(10):711–23.

- Feinberg ME, Kan ML, Hetherington EM. The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. J Marriage Fam. 2007;69(3):687–702.

- Panksepp J, Biven L. The archaeology of mind : neuroevolutionary origins of human emotions. W.W Norton; 2012. 562 p.

- Steele H, Steele M, Croft C. Early attachment predicts emotion recognition at 6 and 11 years old. Attach Hum Dev [Internet]. 2008;10(4):379–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=pubmed&DbFrom=pubmed&Cmd=Link&LinkName=pubmed_pubmed&LinkReadableName=Related Articles&IdsFromResult=19016048&ordinalpos=3&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

- McMilllan AS, Barlow J, Redshaw M. Birth and beyond: A Review of the Evidence about Antenatal Education. Epidemiology [Internet]. 2009;(November):1–112. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_110371.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidan

- Preparation for Birth and Beyond: A Resource Pack for Leaders of Community Groups and Activites [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215386/dh_134728.pdf

- Gilmer C, Buchan JL, Letourneau N, Bennett CT, Shanker SG, Fenwick A, et al. Parent education interventions designed to support the transition to parenthood: A realist review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;59:118–33.

- Kane GA, Wood VA, Barlow J. Parenting programmes: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Child Care Health Dev [Internet]. 2007;33(6):784–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17944788

- Campbell D, Palm G. Group Parent Education: Promoting Parent Learning and Support [Internet]. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2004 [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: http://sk.sagepub.com/books/group-parent-education

- Kessels RPC. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med [Internet]. 2003;96(5):219–22. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=539473&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22508971

- Smith-lovin L, Brody C. Interruptions in Group Discussions : the Effects of Gender and Group Composition *. Source Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54(3):424–35.

- Hughes M, Vass A. Strategies for closing the learning gap. Network Educational Press; 2001. 288 p.

- Smith A, Lovatt M, Wise D. Accelerated learning : a user’s guide. Network Educational Press; 2003. 120 p.

- Prensky M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. From Horiz [Internet]. MCB University Press; 2001 [cited 2017 Jul 31];9(5). Available from: http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky – Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants – Part1.pdf

- High PC, Klass P. Literacy Promotion: An Essential Component of Primary Care Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 31]; Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/134/2/404.full.pdf

- Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, Riddell T, Wills M, Lin R-B, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control [Internet]. 2005;14:255–61. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/14/4/255.full.pdf

- Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, Dillon L, Zabinski M, Rock CL, et al. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1).

- Hurling R, Catt M, Boni MD, Fairley BW, Hurst T, Murray P, et al. Using internet and mobile phone technology to deliver an automated physical activity program: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2007;9(2):e7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17478409

- Riva G, Preziosa A, Grassi A, Villani D. Stress management using UMTS cellular phones: a controlled trial. Stud Health Technol Inform [Internet]. 2006;119:461–3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16404099

- SmartMom Canada | Optimal Birth BC [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: http://optimalbirthbc.ca/smartmom-canada/

- Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, Whittaker R, Edwards P, Zhou W, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. Elsevier; 2011 Jul 2 [cited 2017 Jul 31];378(9785):49–55. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21722952

- Myles M. Mothercraft Teaching by Midwives. In: A Textbook For Midwives. Edinburgh: E & S Livingstone; 1964. p. 693–766.

- Tohotoa J, Maycock B, Hauck YL, Howat P, Burns S, Binns CW. Dads make a difference: an exploratory study of paternal support for breastfeeding in Perth, Western Australia. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:15.

- Everett KD, Bullock L, Gage JD, Longo DR, Geden E, Madsen R. Health risk behavior of rural low-income expectant fathers. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(4):297–306.

- Ingram J, Johnson D. A feasibility study of an intervention to enhance family support for breast feeding in a deprived area in Bristol, UK. Midwifery. 2004. p. 367–79.

- Ramchandani PG, Domoney J, Sethna V, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, Murray L. Do early father-infant interactions predict the onset of externalising behaviours in young children? Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2013;54(1):56–64.

- Plantin L, Olukoya AA, Ny P. Positive Health Outcomes Of Fathers’ Involvement In Pregnancy And Childbirth Paternal Support: A Scope Study Literature Review. Fathering. 2011;9(1):87–102.

- Hudson DB, Campbell-Grossman C, Fleck MO, Elek SM, Shipman A. Effects of the New Fathers Network on first-time fathers’ parenting self-efficacy and parenting satisfaction during the transition to parenthood. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs [Internet]. 2009;26(4):217–29. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01460860390246687

- Hagger-Holt S, Hagger-Holt R. Pride and joy : a guide for lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans parents [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. 255 p. Available from: http://www.pinterandmartin.com/pride-and-joy.html

Long description

Figure 9-2. This diagram shows the cyclical relationship between the 6 steps in the reflection process. The six steps are: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action plan.

Starting at the top of the cycle, the first box is labeled description: what happened. This is connected by an arrow to the next box labeled feelings: what were you thinking and feeling? This is connected by an arrow to the third box labeled evaluation: What was good and bad about the experience? This is connected by an arrow to analysis: what else can you make of the situation? This is connected by an arrow to conclusion: What else could you have done? This is connected by an arrow to action plan: If it arose again, what would you do? This has an arrow that connects back to the first box ‘description.’ [Return to Figure 9-2]