6 Midwifery Care & Human Rights

Lorna McRae, RM; Karyn Kaufman, DrPH

A human is not isolated like an island, but is interconnected with families and communities. (1, p.15)

The work of midwives around the world is based on human connection. The relationship between midwives, families and communities is both a powerful and a privileged connection that is ideal for furthering social justice. Quality midwifery care incorporates values and philosophy that arise from a human rights perspective, a perspective that takes account of social determinants of health and their contribution to health.

This chapter explores several aspects of what it means to incorporate a human rights perspective into the work of midwifery. It will provide an overview of selected statements found in midwifery codes of ethics that underline the necessity for a human rights perspective and describe a human rights approach, what is meant by social determinants of health and how they relate to health inequities. It will also provide a specific focus on the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada.

2.1 Midwifery Codes of Ethics

There is a moral imperative for midwives to care for mothers and babies regardless of their context or circumstances. As stated by McRae, (2) ‘there is an ethical imperative based on the principles of fairness and the universal human right to the highest attainable standard of health to rectify health disparities.’ (p.182) This ethical stance establishes a human rights approach to women, newborns and families around the globe, an approach that is echoed in codes of ethics for midwives.

2.1.1 Midwifery Professional Associations

2.1.1.1 International Confederation of Midwives (ICM)

The ICM is the international midwifery association that speaks globally for and about midwifery. Its Code of Ethics for Midwives (the Code) (3) ‘acknowledges women as persons with human rights, seeks justice for all people and equity in access to health care, and is based on mutual relationships of respect, trust and the dignity of all members of society.’ (p.1)

The Code directs midwives to develop partnerships, facilitate informed decision-making, and ‘empower women/families to define issues affecting the health of women and families within their culture/society.’ (3, p.1) The Code also states that ‘midwives respond to the psychological, physical, emotional and spiritual needs of women seeking health care, whatever their circumstances.’ (3, p.2) This is a clear call to act in non-discriminatory ways. In addition, the Code states that midwives ‘together with women, work with policy and funding agencies to define women’s needs for health services and to ensure that resources are fairly allocated considering priorities and availability.’ (3, p.1) Here we have support for midwifery advocacy at all policy levels to improve approaches to care for women, their babies and families. Together, the selected statements from the ICM illustrate the centrality of a human rights approach to the provision of midwifery services. Given the extensive data about the global health, economic, social and political inequities for women (and children), the work of responding to inequities in our daily practice is critically important.

External Link

The International Congress of Midwives website is http://internationalmidwives.org/

2.1.1.2 Canadian Association of Midwives (CAM)

CAM is the professional association that represents midwives and the profession of midwifery across Canada. One of its expressed values is the belief that midwives must ‘respect and embrace human dignity, diversity and equity in every facet of their work with clients and colleagues.’ (4) CAM advocates at the national level for the potential of midwifery to enhance the wellbeing of individuals, families and society thereby acknowledging its ethical and organizational responsibility to contribute to improved health for all.

External Link

The Canadian Association of Midwives website is https://canadianmidwives.org

2.1.1.3 Provincial Midwifery Associations

Midwifery services in Canada are provincially/territorially legislated and each jurisdiction has a professional association that advocates for midwives. The basic principles of informed choice, pregnancy as a state of health, continuity of care, and choice of birthplace are imbedded in descriptions of midwifery care across the country and reflect similar values and philosophy. For example, the following statement is from The Association of Midwives of Newfoundland and Labrador (5): ‘Midwifery care should be a choice for all women with uncomplicated pregnancies, regardless of geographic location, socioeconomic status, age, cultural background, gender orientation or religious persuasion.’ (p.1)

Observing the right of women to participate in decision making about care supports non-discrimination since midwives must listen to women and provide time for women to find their own voice. In short, it recognizes the human rights of women seeking care.

2.1.2 Midwifery Regulatory Bodies

Each Canadian province and territory that regulates midwifery has a designated organization (most often a regulatory College) whose primary purpose is public protection. Therefore, a regulatory body functions in the public interest by setting registration/re-registration criteria and publishing standards and policies regarding professional behaviour and clinical practice. The regulating authorities together form the Canadian Midwifery Regulators Council and it makes the following statement about the importance of Canadian midwifery to health and well-being (6): ‘Midwifery care in Canada is based on a respect for pregnancy and childbirth as normal physiological processes. Midwives promote wellness in women, babies and families, taking the social, emotional, cultural and physical aspects of a woman’s reproductive experience into consideration.’ (p.1)

Putting this general statement into practice means having an understanding of human rights and determinants of health, and the ability to truly take the context of women’s lives ‘into consideration.’

The College of Midwives of Ontario regulates the largest group of midwives in Canada. A clear statement about protecting human rights is included in its Code of Ethics. (7)

Each midwife is accountable for their practice, and in the exercise of professional accountability, shall: Provide care which respects individuals’ needs, values and dignity, and does not discriminate on the basis of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability. (p.1)

Given that this statement comes from a midwifery regulator it imposes a direct responsibility upon midwives to uphold and protect the human rights of clients and their families.

The examples mentioned are illustrative of statements found in codes of ethics at the international, national and provincial/territorial levels of the profession. Midwifery is not different from other health professions in advancing a code of ethics for its members. Similar statements can be found for nurses, (8) physiotherapists, (9) physicians (10) and indeed many more professions. Midwives collaborate with several other professions and though our actions and attitudes may differ at times, the common ground is in codes of ethics where statements about respect, dignity and human rights are readily found.

2.2 Human Rights & Social Determinants of Health

International, national and provincial midwifery Codes of Ethics provide a dynamic platform from which to participate in upholding human rights and increasing equitable outcomes for all mothers, newborns, families and their communities. Sanghera, et al., writes, ‘A human rights approach is based on accountability and on empowering women, children and adolescents to claim their rights and participate in decision making, and it covers the interrelated determinants of health and well-being.’ (10, p.42)

This section will now turn to furthering a conceptual understanding of the inter-related nature of human rights, social determinants of health and health inequities. The following concepts are important for this understanding:

Health inequalities: Differences, variations and disparities in health status and risk factors of individuals and groups that need not imply moral judgement. Some inequalities reflect random variations (i.e. unexplained causes), while others result from individual biological endowment, the consequences of individual choices, social organization, economic opportunity, or access to health care. (12)

Equity: The absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in key indicators among social groups. It is both a process and a goal. It involves the recognition of difference in treating everyone fairly. Sometimes it means treating people differently in order to achieve equality. (13)

2.2.1 Human Rights

The Canadian Human Rights Commission states, ‘Human rights define what we are all entitled to – a life of equality, dignity and respect; a life free from discrimination. You do not have to earn them. It’s the same for every man, woman and child on earth’ (12, p.1). Equality, dignity and respect for all regardless of income, education, race, ethnicity, age, ability and social status remains an elusive ideal but one towards which everyone can work.

Did You Know?

John Rawls, an American political philosopher, developed a theory to help illustrate the many social, political and economic factors that influence the practical application of human rights, justice, and fairness in our society. His ‘veil of ignorance’ thought experiment is explained clearly in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-JQ17X6VNg

The Canadian Human Rights Act protects persons from discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, family status, disability, a conviction for which a pardon has been granted or a record suspended. There is abundant evidence nationally that when these aspects of human rights are not upheld there are negative effects on socioeconomic status and health. (14,15)

A further protection was advanced by the Canadian Association of Midwives (CAM) in 2015 in the organization’s Statement on Gender Inclusivity & Human Rights, (16) which reads in part:

We are committed to including trans, gender queer, intersex and marginalized communities in our central dialogue and ensuring that CAM is inclusive in its statements, actions and in all aspects of its work. These priorities are not established by the needs of the majority but by the importance of the inclusion of all people. (p.1)

The document continues:

We are aware that transphobia disproportionately affects those with other, often intersecting, marginalized identities such as racialized persons, self-identified Indigenous people, those living as colonized people, those living with the legacy of residential schools, differently abled people and all living with the effects of the social determinants of health. (p.1)

2.2.1.1 The Role of Reflection

The CAM Statement is a clear example of a professional commitment to using a human rights approach to address discrimination and the resulting inequities in health care experienced by individuals. Having an intentional human rights perspective requires a commitment to the principles of praxis (the continual interplay between reflection and action), the personal (that who we are and where we come from matter deeply in addressing health inequities), and partnership (community building amongst individuals with varied demographic backgrounds). (17)

Reflection on our personal and our communities’ experiences stemming from our race, class, sex, abilities, gender orientation and identity, and sexual orientation is essential when considering the challenges and opportunities in working together towards greater equality and protection of human rights for all. Considering questions such as ‘Who am I?’ and ‘Where did I come from?’ is work that is psychologically and spiritually challenging. Our personal and professional relationships of power and privilege are not static. We age, our abilities may temporarily or permanently change, and our incomes increase or decrease. Other aspects of our identities, such as the colour of our skin, or the kind of family we were born into, don’t change. Our perspective is both limited and expanded by the specificities of our lives, which, if unexamined, can lead to a failure to see our interconnectedness. Our knowledge of power and privilege should and must inform a strong ethical and human rights approach to our work as midwives.

In an effort to genuinely discuss the everyday trauma and resilience of people facing inequities, I respectfully and proudly use my history in my family and communities to illustrate that where we come from matters deeply. My history includes being the 10th of 14 children, raised in a context of poverty. When I look at family photos the caricature of poverty is evident in our mismatched clothing, our unkempt hair and the dirt under our fingernails. However, those deeply ingrained and stereotypical images of poverty tell nothing of my richly complex and dynamic family. When talking and thinking about people and communities that are marginalized and have poor outcomes, we need to look more deeply. Nancy Scheper-Hughes, (18) writing about mother love and infant mortality in an impoverished area of Brazil, says,

I am searching for a more intimate, less alienating way to talk about social class formation… one that takes into account cultural forms and meanings as well as the political economy. Although the foresters could be described as a ‘displaced rural proletariat’ or even as a new formed ‘urban class,’ they are both of these and yet a good deal more. They are poor and exploited workers, but theirs is not simply a ‘culture of poverty,’ nor do they suffer from a poverty of culture. Theirs is a rich and varied system of signs, symbols and meanings. (p.91)

People are negatively impacted by racism, classism, sexism, ableism, ageism and other identities. Stereotypes result from believing that all people with a particular characteristic are the same. Stereotyping is revealed in our responses to marginalized groups and is an insidious and powerful force within society. To reiterate – who we are and where we come from matters and we must know ourselves to engage in a human rights approach to midwifery care.

Reflect

Read the following thorough discussion of Power and Privilege by Maisha Z. Johnson:

http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/07/what-privilege-really-means/

What are three areas of privilege in your current circumstance?

Can you recall an instance when you used privilege to increase or decrease your sensitivity to people you interact with in your current circumstance?

2.2.1.2 Right to Health

The right to health is viewed as fundamental and is recognized by several legal codes and treaties relating to human rights, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the Convention of the Rights of the Child; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. (11) When considering health as a right, it is important to take account of the World Health Organization (WHO) (19) definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (p.1). However, determining whether an individual or group or country is ‘healthy’ is daunting. There is no perfect measure of the several dimensions of health that are included in the WHO definition.

Despite its limitations, a frequently used measure of the health of a population is life expectancy. The WHO Global Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSHD) begins a report (20) with a sombre statement, ‘our children have dramatically different life changes depending on where they were born. In Japan or Sweden, they can expect to live more than 80 years; in Brazil, 72 years, India, 63 years; and in one of several African countries, fewer than 50 years.’ (p.26)

External Links

The International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights can be found here:

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

The Convention on the Rights of the Child can be found here: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women can be found here:

http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/cedaw.pdf

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples can be found here: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities can be found here:

http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights can be found here: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx

Even within Canada, which enjoys a high ranking (tied 9th with New Zealand out of 188 countries) on the Human Development Index, (21) where a long and healthy life is one of the primary measures, Statistics Canada reports (22) ‘gaps between Aboriginal groups and the general Canadian population varied from 5 years to 14 years in 2001.’ (p.22)

Using studies from nations like Canada that are termed ‘developed,’ Galea et al., (23) published findings from a meta-analysis about the number of deaths attributable to social factors. From over 400 studies, 47 of which met their evidence criteria, they concluded the number of deaths attributable to six social and interrelated factors (low education, poverty, low social support, area-level poverty, income inequality and racial segregation) was similar to the number of deaths from pathophysiological and behavioural causes. Findings from countries at all levels of income show that health and illness follow a social gradient: the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the population health. (20)

The health sector in every country can use internationally and nationally recognized human rights mechanisms for pressuring regional, national and international bodies for social, economic and political reforms and policies to decrease health inequities. The right to health applies to all women and their babies. Midwives can provide care that attends not only to the physical survival of the birthing parent and baby, but also to their psychological and emotional well-being through the life course. (24)

Despite the stance that health is a right, the evidence is clear that there are unequal outcomes related to many aspects of who we are, where we live and how well we live. We are born into communities and develop multiple identities, which intersect with social, political and economic realities. Health is affected by these realities, thus the focus on understanding the impact of these social factors/determinants of health.

2.2.2 Social Determinants of Health

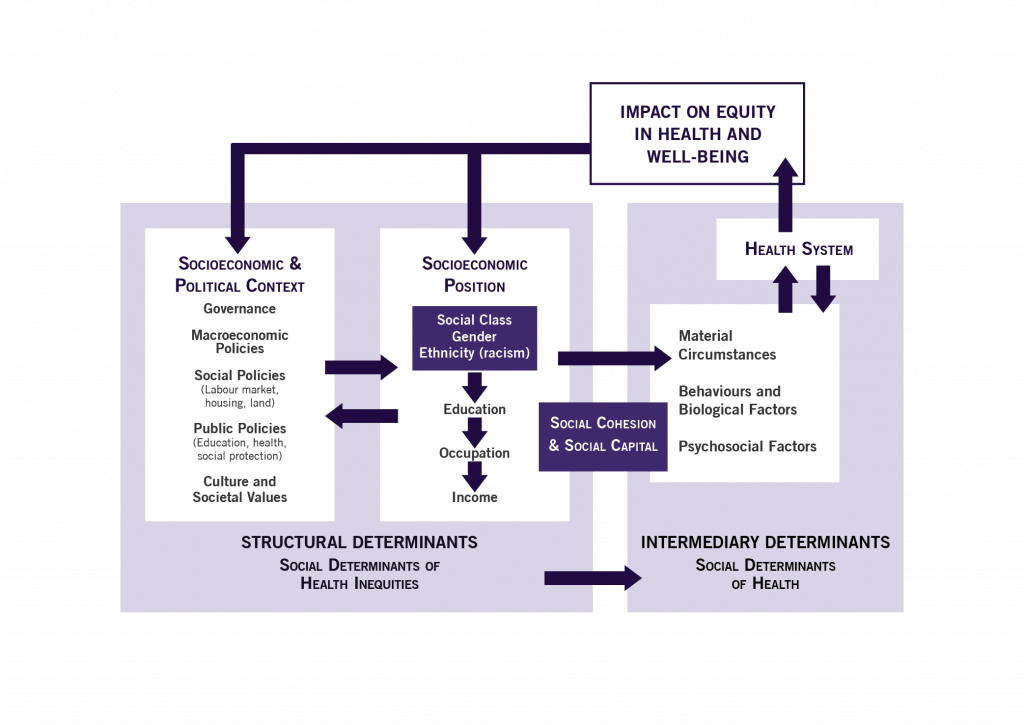

The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health outlines an evidence informed framework for understanding the mechanisms of health inequities and the actions that can be taken to decrease those disparities (Figure 2-1). (20)

The far left side of the diagram shows elements of the socioeconomic and political context that are

broadly defined to include all social and political mechanisms that generate, configure and maintain social hierarchies, including the labour market; the educational system, political institutions and other cultural and societal values. … Structural mechanisms are rooted in the key institutions and processes that are part of the socioeconomic and political context. (19, p.9)

Key institutions, as referred to in the above quote, hold a great deal of power in all societies. However, that power is not absolute and can be challenged, successfully. Duflo and Banerjee (25) outline some of the examples of their randomized experiments to create institutional change that offer a measure of optimism. They note the success of creating change through actions such as publicizing corrupt practices or threatening audits.

Often, small changes make important differences. In Brazil, switching to a pictorial ballot enfranchised a large number of poor and less educated adults. As a result, the politicians they elected were more likely to enact policies that assisted the poor. In China, even very imperfect elections led to policies that were more favourable to the poor. In India, when quotas for women on village councils were enacted, women leaders invested in public goods preferred by women. A 2016 example from Canada is the prolonged, but successful, nine-year legal battle waged by Dr. Cindy Blackstock and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada about the underfunding of child welfare services on reserves compared to funding for children who lived off reserve. The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal rejected the government’s arguments that the Canadian Human Rights Act should not override decisions about funding to First Nations communities. (26)

The second left column of the framework depicts the elements of socioeconomic position: income, education, occupation, social class, gender, race/ethnicity. The interactions of these elements with the socioeconomic and political context are together conceptualized as structural determinants within the larger portrayal of social determinants of health inequities. They are shown to directly impact the third column (right side of the diagram).

The circumstances depicted in the third column are what we each see and experience to some degree or other. The differences in material circumstances (housing, neighborhood quality, food security, water), psychosocial circumstances (individual and community stressors, social supports, coping abilities), and behavioral and biological factors (nutrition, physical activity, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, genetics, diseases) directly affect health and well-being. Also evident in the diagram is the cyclical nature of this relationship. Persons who experience poorer health may experience a loss of socioeconomic position, often due to job limitations, reduced income, poorer housing, etc., which, in turn, continues to impact health outcomes.

The diagram makes clear that the health system is only one factor that can contribute to reducing health inequities. This is not to minimize the importance of ethical and respectful care from midwives and others, but all providers need to recognize that, ‘Structural societal factors, such as poverty, gender inequality, and other forms of discrimination (such as racism) and inequality directly and indirectly affect reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and generate health inequities.’ (26, p.36) Interventions to mitigate these adverse factors are complex and require a host of changes to, for example, reduce poverty, end child marriage, and stop violence against women and children.

The relationship between social factors and health has been shown by Richard Wilkinson (28). Wilkinson’s research found parallels between studies of weight gain in babies and studies of deaths and income distribution in adults. In each group the importance of meeting social needs was found to be significant. For the infants, it was interaction with loving caregivers that was shown to be critical to their weight gain and development. Researchers used indicators from the International Index of Health and Social Problems, such as life expectancy, teen births, obesity, mental illness, homicides, imprisonment, infant mortality, to demonstrate that the greater the income differences within a society, the less well-being there is for all members of that society.

An added perspective to incorporate into considerations of social determinants of health is that of life course. This term is used by epidemiologists, economists, political theorists, statisticians and health care providers. (24, 28–33) While it seems evident that the past is always present, life course theory holds that one’s health status reflects both historical and contemporaneous conditions. This perspective is evident in Reading and Halseth (35).

Social determinants can include cultural, economic, and political forces which interact in a multitude of ways to contribute to or harm the health of individuals and communities. The impact of these forces during childhood can have long-lasting health implications through the life course since material deprivation can influence child and adult circumstances and behavior. The interactions between these various forces are important parts of the health and disease puzzle. (p.5)

2.2.3 Contributing to Action

The material in this section has introduced theoretical perspectives about the inter-related nature of human rights, social determinants of health and health inequities. The hope is that it provides a greater understanding of problems where human rights are compromised, inequities persist and there are continuing consequences for human health. Through this increased understanding of health inequities midwives can contribute to solutions.

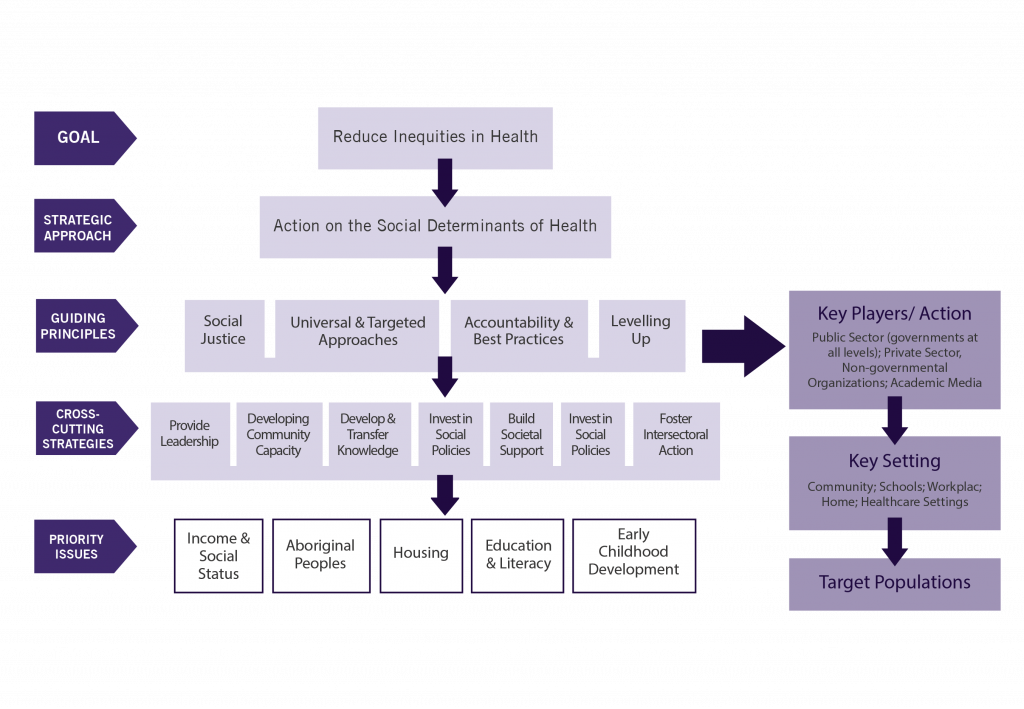

The Public Health Agency of Canada, the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, the Canadian Population Health Initiative, the Canadian Public Health Association, the Institute of Population and Public Health, and the Population Health Promotion Expert Group of the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network worked together to construct a framework for actions to reduce health inequities (Figure 2-2).

The strategies for change arise from considering the social determinants of health and cut across multiple sectors in order to address priority issues, which include Aboriginal peoples and early childhood development. These are issues that engage midwives, individually and collectively. Midwives can be part of actions that lead toward equity. While there is much work to do, an evidence informed approach is our responsibility.

2.3 A Focus on the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

Social determinants of health have special resonance for the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada, among whom indicators of health status demonstrate persisting inequalities, including a gap in life expectancy between Aboriginal groups and the general Canadian population. Statistics Canada data from 2011 showed that the probability of living to age 75 for both men and women who were age 25 and were Registered Indians, non-status Indians or Métis was 10-19 percentage points lower than for all men and women of comparable age. (38)

Further evidence of disparities comes from the Community Well-Being (CWB) scale for First Nations, developed by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, which measures education, labour force participation, income and housing. It indicates that Aboriginal communities represent 65 of the 100 unhealthiest Canadian communities. (38) The effects of these inequitable social determinants of health are evident in the poorer physical, mental, and emotional health of many Indigenous peoples. The complex interaction between various social, political, historical, cultural, environmental, economic and other forces are increasingly understood to shape health for individuals that must be addressed through a social determinants approach. (39)

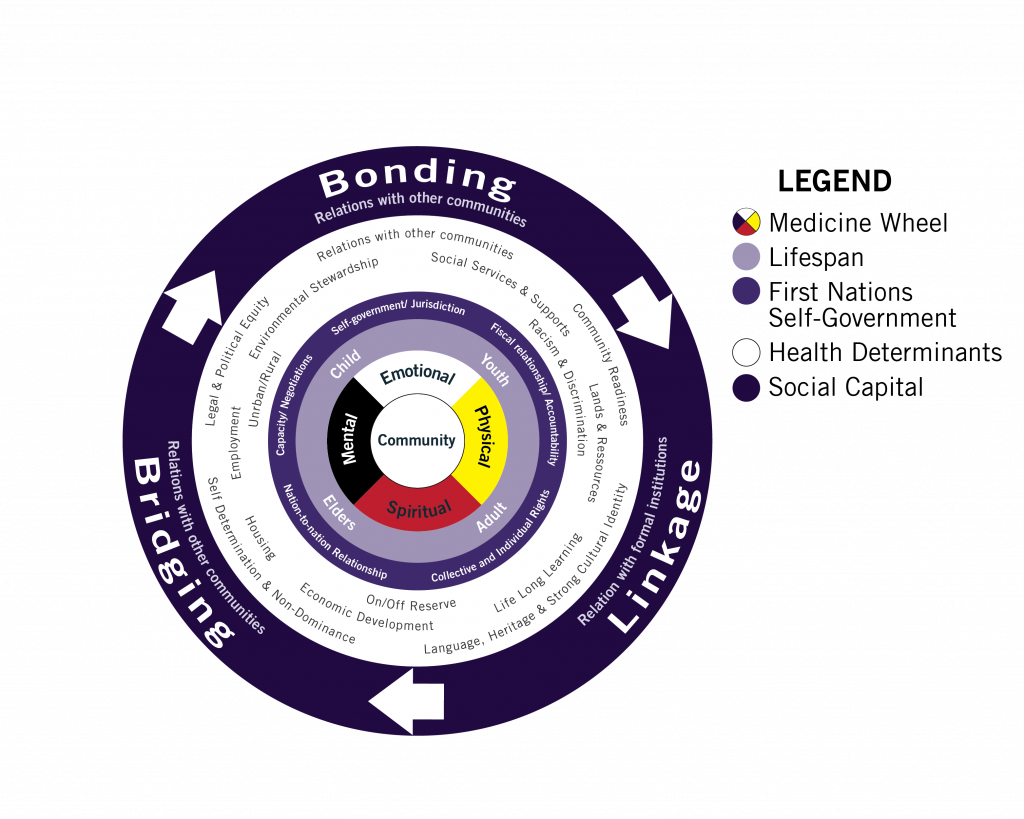

In 2013, the Assembly of First Nations developed the framework in Figure 2-3. It is highly specific to First Nations and created to address the fact that First Nations people have poorer health outcomes than most Canadians.

The framework includes a circle with many health determinants. These have been echoed by Indigenous studies scholar Yvonne Boyer (1) who examined historical and current Canadian legal policies and their impact on health. She identified six determinants of health: poverty, poor quality housing and overcrowding, poor water quality, geography and its impact on access, environmental factors, and colonialism. The impact of the Canadian policy of colonialism on Indigenous people is supported by Kreiger and Beckfield’s epidemiologic review of how political systems and priorities shape inequalities. (33) Special emphasis is given to geography by Sarah de Leeuw (41) who suggests that, ‘geography as a physical and material entity – place, weather, land, space, ecology, territory, landscape, water, ground, social and the like – is a remarkably powerful determinant of Indigenous peoples’ health that is not, cannot, and should not be encapsulated with a ‘social’ determinants of health framework.’ (p.90)

2.3.1 Midwifery Initiatives to Address Inequities

This brief overview of conceptualizations about determinants of health for Aboriginal Peoples of Canada cannot do justice to the topic, and can serve only as an introduction to some actions within Canadian midwifery to address inequities. In 2015, the Midwives Association of British Columbia secured provincial funding for all its members to enrol in the Indigenous Cultural Competency core health training course designed by the Provincial Health Services Authority to enhance knowledge of Indigenous peoples, increase self-awareness, and strengthen service providers’ skills to work with Indigenous Peoples.

At a broader level, the National Aboriginal Council of Midwives (NACM) ‘advocates for the restoration of midwifery education, the provision of midwifery services, and the choice of birthplace for all Aboriginal communities, consistent with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ (41, p.3); and ‘promotes excellence in reproductive health care for Inuit, First Nations and Métis women’ (43, p.1).

External LInk

Visit the NACM website here: http://aboriginalmidwives.ca/

Did You Know?

In 2007, UNDRIP was adopted by the UN General Assembly with 144 states endorsing the Declaration. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States voted against it. In 2010, Canada endorsed it as an aspirational document but then did not adopt the action-oriented outcome document in 2014. (44) On June 15, 2017, the joint AFN-Canada Memorandum of Understanding on Joint Priorities was signed, committing the Government of Canada to work in partnership on a number of priorities including full and meaningful implementation of United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including co-development of a national action plan and discussion of proposals for a federal legislative framework on implementation. (45)

External Link

NACM has created several resources on the significance of Aboriginal midwifery.

Videos:

Aboriginal Midwifery can be found here: http://www.isuma.tv/en/national-aboriginal-council-of-midwives/aboriginal-midwifery-video

The Job of an Aboriginal Midwife can be found here: http://www.isuma.tv/en/national-aboriginal-council-of-midwives/aboriginal-midwives

Downloadable PDFs:

Restoration and Renewal of Aboriginal Midwifery can be found here: http://aboriginalmidwives.ca/sites/aboriginalmidwives.ca/files/pamphlet-three-double_panels.pdf

Aboriginal Midwifery in Practice can be found here: http://aboriginalmidwives.ca/sites/aboriginalmidwives.ca/files/pamphlet-two-double_panels.pdf

NACM is working to bring to fruition the spirit of Article 23 of UNDRIP that states (1) ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to be actively involved in developing and determining health, housing and other economic and social programmes affecting them.’ (p.164) ‘As a strong national Indigenous midwifery organization, NACM has an important leadership role in maternal-child and Indigenous health in Canada and globally. There are several ways NACM members individually and collaboratively contribute to the broader goal of equitable access to care and self-determination of Indigenous people’s health.’(41, p.12)

The return of birth to Aboriginal communities is of special interest because of long standing practices in many Aboriginal communities to transport pregnant women away from their home community to a large centre to await the birth. Women often spend several weeks separated from family and friends in unfamiliar surroundings, away from their usual food and language and social support network. A project to return birth to an Aboriginal community is an impressive example of a specific and sensitive intervention. An assessment of the experience of Inuit women in Nunavik, Quebec from 2000‐2007 revealed low rates of intervention with safe outcomes in the more than 1300 young, largely multiparous, Inuit group. The local birth facilities involved a team approach with midwives, physicians and nurses, with 85% of births attended by midwives. This model of care developed over a long period and has been a sustained community‐professional collaborative effort to screen appropriately, to support women who must be transferred for medical reason, to return birth to remote communities and to build midwifery skills in Aboriginal women. (46,47)

External Links

NACM has created a variety of media to describe Aboriginal midwifery and its impact on Aboriginal midwives themselves, and the communities they serve. Interview clips (mp3) with seven Aboriginal midwives can be found here:

2.4 Conclusion

This chapter has shown the central place of human rights within the professional codes of ethics set out for midwives. Enacting those codes requires that midwives understand how health inequities are linked with social determinants and failures to observe the right to health. We must be explicit that our codes of ethics are inextricably linked to actions that reflect the human right to health and dignity. An approach to midwifery provision of care, regulation of the profession and education of future and current midwives can use an intentional human rights perspective to reveal social, economic and political injustices. With careful, sensitive and specific interventions midwives can be a vital resource for improving outcomes for childbearing clients and newborns, and furthering sustainable local, national and global development goals. These goals matter deeply to each of us and to our communities.

References

- Boyer Y. Moving Indigenous Health Forward; Discarding Canada’s Legal Barriers. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing; 2014.

- McRae DN, Muhajarine N, Stoll K, Mayhew M, Vedam S, Mpofu D, et al. Is model of care associated with infant birth outcomes among vulnerable women? A scoping review of midwifery-led versus physician-led care. SSM – Population Health. 2016. p. 182–93.

- International Confederation of Midwives Core Documents [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://internationalmidwives.org/knowledge-area/icm-publications/icm-core-documents.html

- Canadian Association of Midwives. Mission and Vision [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 13]. p. 1. Available from: https://canadianmidwives.org/mission-vision/

- Association of Midwives of Newfoundland and Labrador [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: www.amnl.ca/Philosophy-Midwifery-Practice- health-concepts.html

- Canadian Midwifery Regulators Council [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.cmrc-ccosf.ca/

- College of Midwives of Ontario Code of Ethics. 2015.

- Association CN. Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses [Internet]. 2017th ed. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association; 2017. 60 p. Available from: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/html/en/Code-of-Ethics-2017-Edition/files/assets/basic-html/page-1.html

- CPA Code of Ethics [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: https://physiotherapy.ca/cpa-code-ethics?lang=en-ca

- Canadian Medical Association. CMA Code of Ethics. C Policy [Internet]. 2015;(March):1–4. Available from: http://www.cma.ca/index.php/ci_id/53556/la_id/1.htm

- Sanghera, J., Gentile, L., Guerras-Delgado, I., O’Hanlon, L., Barragues, A., Hinton, RL., Khosla, R., Rasanathan, K., Stahlhofer M. Human Rights in the new Global Strategy. BMJ. 2015;14(351).

- Daghofer D, Edwards P. Toward Health Equity: A Comparative Analysis and Framework for Action. 2009.

- What are human rights [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/what-are-human-rights

- Mikkonen J, Raphael D. Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. [Internet]. The Canadian Facts. 2010. 62 p. Available from: http://www.thecanadianfacts.org

- Raphael D. A discourse analysis of the social determinants of health. Crit Public Health. 2011;21(2):221–36.

- Canadian Association of Midwives. A statement on Gender Inclusivity & Human Rights [Internet]. Montreal; 2015. p. 1. Available from: http://canadianmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CAM-GenderInclusivity-HumanRights-Sept2015.pdf

- Westerhaus M, Finnegan A, Haidar M, Kleinman A, Mukherjee J, Farmer P. The necessity of social medicine in medical education. Acad Med [Internet]. 2015;90(5):565–8. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00001888-201505000-00013%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25406609

- Scheper-Hughes N. Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. Unviersity of California Press; 1992.

- Constitution of WHO: principles [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the socialdeterminants of health. World Heal Organ [Internet]. 2008;40. Available from: http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsacd/cd68/Marmot.pdf%5Cnpapers2://publication/uuid/E1779459-4655-4721-8531-CF82E8D47409

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2016 Human Development for Everyone [Internet]. United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/

- Projections of the Aboriginal populations, Canada, provinces and territories 2001 to 2017 [Internet]. Ottawa; 2005. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-547-x/91-547-x2005001-eng.pdf

- Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, DiMaggio C, Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the united states. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1456–65.

- Right to Health [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.humanrightsinchildbirth.org/right-to-health/

- Banerjee A, Duflo E. Poor Economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty [Internet]. Public Affairs; 2011. 320 p. Available from: http://www.pooreconomics.com/chapters/10-policies-politics

- Neve A. A great victory for First Nations families and for human rights in Canada. Rights!Now. Ottawa; 2016;

- Rasanathan K, Damji N, Atsbeha T, Brune Drisse M-N, Davis A, Dora C, et al. Ensuring multisectoral action on the determinants of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health in the post-2015 era. BMJ [Internet]. 2015;351(9745):h4213. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26371220

- Wilkinson R, Picket K. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. 2nd ed. Penguin Books; 2010. 400 p.

- Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus: The need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1 SUPPL. 1).

- Adler NE, Stewart J. Preface to The Biology of Disadvantage: Socioeconomic Status and Health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:1–4.

- Burton-jeangros C, Editors DB, Howe LD, Firestone R, Tilling K, Lawlor DA. A Life Course Perspective on Health Trajectories and Transitions. Springer [Internet]. 2015;4:39–61. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-20484-0

- Kornelsen J, McCartney K. System enablers of distributed maternity care for aboriginal communities in british columbia: findings from a realist review. 2015.

- Beckfield J, Krieger N. Epi + demos + cracy: Linking Political Systems and Priorities to the Magnitude of Health Inequities—Evidence, Gaps, and a Research Agenda. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):152–77.

- Mullainathan S, Shafir E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. New York, NY: Time Books; 2013.

- Reading J, Halseth R. Pathway to Improving Well-being for Indigenous People: How Living Conditions Decide Health. Prince George; 2013.

- A Review of Frameworks on the Social Determinants of Health. 2015.

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/

- Nations A of F. First Nations Holistic Policy and Planning: A Transitional Discussion Document on the Social Determinants of Health [Internet]. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations; 2013. Available from: http://health.afn.ca/uploads/files/sdoh_afn.pdf

- Reading CL, Wein F. Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. Natl Collab Cent Aborig Heal [Internet]. 2009;1–47. Available from: http://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/docs/social determinates/nccah-loppie-wien_report.pdf

- Hardin C, Banaji M. The Nature of Implicit Prejudice: Implications for Personal and Public Policy. In: Shafir E, editor. The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press; 2012. p. p13-31.

- De Leeuw S. Activating Place Geography as a Determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ Health and Well-being. In: Greenwood, M, De Leeuw, S, Lindsay, NM, Reading C, editor. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada, Beyond the Social. Canadian Scholars Press; 2015.

- National Aboriginal Council of Midwives. Situational Analysis 2017: Rooted in our past looking to our future [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://canadianmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NACM_SituationalAnalysis_2017_Low-resolution.pdf

- National Aboriginal Council of Midwives [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 1]. Available from: http://aboriginalmidwives.ca/

- United Nations Declaration. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations Gen Assem [Internet]. 2008;(Resolution 61/295):10. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

- Nations A of F. Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://www.afn.ca/policy-sectors/implementing-the-undeclaration

- Van Wagner V, Epoo B, Nastapoka J, Harney E. Reclaiming Birth, Health, and Community: Midwifery in the Inuit Villages of Nunavik, Canada. J Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2007;52(4):384–91.

- Couchie C, Sanderson S. A Report on Best Practices for Returning Birth to Rural and Remote Aboriginal Communities. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. 2007;29(3):250–4.

Image Long Descriptions

This diagram shows the interrelated relationship of socioeconomic position, social capital, political and social policies, and gender and ethnic factors, to overall health and wellbeing. At the top of the cycle is a box labelled ‘Impact on Equity in Health and Well-being.’ Arrows (indicating impact) flow from this into a larger box labelled ‘Structural Determinants: Social Determinants of Health Inequities.’

This Structural Determinants box is separated into two compartments. On the left, the compartment is labelled ‘Socioeconomic and Political Context’ and it includes: governance, macroeconomic policies, social policies (labour market, housing, land), public policies (education, health, social protection), culture and societal values. On the right, the compartment is labelled ‘Socioeconomic Position’ and it first includes a package labelled social class, gender, and ethnicity (racism). Arrows show that this package impacts education, occupation, and income, all within the socioeconomic position compartment. Arrows also connect the socioeconomic and political context compartment and the socioeconomic position compartment to show that these factors can influence each other.

The encompassing Structural Determinants: Social determinants of health inequities box is connected (via arrows) to a second encompassing box labelled Intermediary Determinants: Social determinants of Health. There is also a bridge between these two boxes labelled ‘social cohesion and social capital’. This bridge connects the ‘socioeconomic position’ compartment to a compartment within the Intermediary Determinants box. This compartment contains material circumstances, behaviours and biological factors, and psychological factors. Arrows flow to/from this compartment to connect a second compartment labelled ‘health system.’ An arrow flows from the health system compartment within the Intermediary Determinants box to the first box: Impact on Equity in Health and Well-being. [Return to Figure 2-1]

A multi-tiered chart. There are 5 tiers top to bottom, and 3 sections left to right. On the left, the first section lists the titles for each tier, moving from top tier to bottom, the titles are: goal, strategic approach, guiding principles, cross-cutting strategies, priority issues.

In the second section, the top tier (goal) lists only one item: reduce inequities in health. A down arrow connects this to the second tier (strategic approach). Only one item is listed in this tier: Action on the social determinants of health. A downward arrow connects this to the third tier (guiding principles). This tier contains four items: social justice, universal and targeted approaches, accountability and best practices, levelling up. This tier is connected by a downward arrow to the fourth tier, and a sideways flowing arrow to the third section.

The third section lists three factors, in three boxes. The first box is labelled key players/action and includes public sector (governments at all levels), private sector, non-governmental organizations, academic media. An arrow flows from this box to the second box labelled ‘key setting’ and includes community, schools, workplace, home, healthcare settings. An arrow flows from this box to a box labelled ‘target populations’.

Returning to the second section, moving from the third tier ‘guiding principles’ to the fourth tier ‘cross-cutting strategies.’ This tier has seven items: provide leadership, developing community capacity, develop and transfer knowledge, invest in social policies, build societal support, invest in social policies, foster intersectoral action. A downward arrow connects this to the final tier ‘priority issues’. This tier contains 5 independent factors: income and social status, aboriginal peoples, housing, education and literacy, early childhood development. [Return to Figure 2-2]

A chart composed of five concentric circles. The inner-most circle is the First Nations Medicine Wheel. At the center of the medicine wheel is a circle labelled ‘community.’ The wheel is then split into four equal parts labelled: emotional, physical, spiritual, mental (health). The next circle outside this represents lifespan and is labelled child, youth, adult, elders. The next circle outside this represents first nations self-government and contains the labels self-government/jurisdiction, fiscal relationship/accountability, collective and individual rights, nation-to-nation relationship, capacity/negotiations. The next circle, the fourth circle, represents health determinants. It contains 16 factors: relations with other communities, community readiness, language, heritage and strong cultural identity, self-determination and non-dominance, legal and political equity, social services and supports, lands and resources, life-long learning, economic development, housing, employment, environmental stewardship, racism and discrimination, on/off reserve, urban/rural. The outermost circle represents social capital. There are three factors labelled, with arrows showing these are part of a cycle/loop. The first factor is bonding (relations with other communities), an arrow then connects this to linkage (relation with formal institutions). An arrow then connects this to bridging (relations with other communities), and finally, an arrow connects bridging back to bonding. [Return to Figure 2-3]