1 Midwife as Practitioner

Allison Campbell, MA, BA, BMW, RM and Lesley Page, CBE, PhD, MSc, BA, RM, HFRCM

All those working in maternity care have shared aims: To support health, wellbeing and a positive experience of care around pregnancy, birth and the early weeks of life; to consider long term as well as short term effects of care; to give the best start in life and family integrity; and to contribute to the growth of secure attachments between parent(s) and baby. These aims also include, but are not limited to, the reduction of mortality and morbidity of mother and baby during pregnancy, birth and postpartum, including the morbidity of unnecessary intervention.

The unique role of the midwife is outlined by the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), emphasizing the importance of (1, p.1):

- Partnership with women to promote self-care and the health of mothers, infants, and families

- Respect for human dignity and for women as persons with full human rights

- Advocacy for women so that their voices are heard

- Cultural sensitivity, including working with women and health care providers to overcome those cultural practices that harm women and babies

- A focus on health promotion and disease prevention that views pregnancy as a normal life event

Midwives around the world practice to these principles, even while providing care in sometimes challenging settings. We serve diverse populations and women with complex lives, health and social care needs. We face wide economic and social inequalities, as well as variations in care and outcomes between different services and populations. We are becoming more aware of the prevalence of mental illness in the perinatal period, of the level and impacts of domestic abuse and violence against women, of the effects of ethnicity and deprivation on the experience and outcomes of maternity. As globalization increases, we are seeing increasing inequalities the world over, and the highest levels of migration since the Second World War. (2) Many women suffer discrimination, injustice, violence and abuse. Many midwives will care for those who are refugees, those seeking asylum, or undocumented migrants. All of these complexities present a need for care that is highly responsive to different population needs, as well as varying needs of the women and their families. It is central to the midwifery model of care to meet each family where they are at, and provide the most responsive, reflective care possible within that context.

Reflect

How would the woman’s situation and life circumstances differ between: a refugee from Syria, a frightened young mother and partner, and a woman whose pregnancy is not going well?

There are significant variations in the way midwives are trained throughout the world. In many countries, midwives are nurses who have garnered additional training in midwifery while in other places in the world, midwives are self-taught and struggle to acquire basic training. In Canada, there is only one route to becoming a professional midwife. All midwives are educated in a four-year university program. Midwives who have been educated and registered in other countries receive education in the Canadian health care system and the Canadian model prior to writing Canadian registration examinations.

External Link

You can learn more about the midwifery education programs in Canada here: http://cmrc-ccosf.ca/canadian-midwifery-education-programs

There are many similarities and also differences in the way midwifery is actually practiced in different countries and health care systems around the world. In this chapter, we will explore the midwife as practitioner within the Canadian health care system. We will discuss the midwifery philosophy of care and how it informs midwives’ approach to working with individual women, their babies and partners. Then we will look more closely at the midwife’s scope of practice, focusing on the five central aspects of the midwifery model of care in Canada: continuity of care, informed decision-making, community-based, choice of birth setting and evidence-informed practice. In the final section, we will discuss some of the unique skills that midwives employ in the provision of care.

5.1 Canadian Midwifery Model

Regulated midwifery is very recent in Canada, although midwives have practiced in indigenous communities since the beginning of human life on what is now known as the North American continent. It was not until the late 20th century that midwives organized to set up professional associations, regulatory bodies and educational programs. (For more on this, visit Chapter 8 – Professional Framework for Midwifery Practice in Canada)

In the late 19th C and early 20th C attending births at home was carried out by the Victorian Order of Nurses in cities and Red Cross nurses in northern areas of Canada That role was relinquished to physician assisted hospital birth in part due to physician power but also because midwives at the time were in no position to organize to integrate midwifery in to the system on a permanent basis. (3)

Regulated midwifery began in Ontario in 1993, and currently, most provinces in Canada have health services which provide access to midwifery care, as well as organizations that support full, professionally autonomous midwifery. (4) There are slight variations in the way midwifery is practiced from province to province, as each provincial health care system is organized slightly differently. However, the midwifery philosophy and model of care are the same across the country, and all midwives in Canada are members, not only of their provincial organizations, but of the Canadian Association of Midwives as well.

External Links

You can learn more about how the Aboriginal Council of Midwives supports and advocates for aboriginal midwives in Canada here: http://aboriginalmidwives.ca/

An overview of midwifery in Canada by the Canadian Association of Midwives can be found here: https://canadianmidwives.org/midwifery-across-canada/

5.2 Philosophy of Care

The meaning of the word midwife in English is ‘being with the woman.’ This has a very specific implication; it means not standing before (the traditional position of the obstetrician) but being beside, on the same level, understanding each other. Midwifery has been described as being a companion on the journey to motherhood, being the professional friend, and being concerned with the making of mothers. This concept of companion, which is embedded in the name itself, is what makes midwives unique practitioners in the health care system.

Traditionally, obstetrics tends to focus on the reduction of risk, which can lead to and inform an epidemic of fear around pregnancy and childbirth. (5) Midwifery, meanwhile, keeps at its center, the understanding that pregnancy, labour and birth are safe, healthy and normal physiological processes. The College of Midwives of British Columbia describes this as a foundation of the midwifery philosophy of care. (6) It states:

Midwifery care is concerned with the promotion of women’s health. It is centred upon an understanding of women as healthy individuals progressing through the life cycle. It is based on a respect for pregnancy as a state of health and childbirth as a normal physiologic process, and a profound event in a woman’s life. (6, p.1)

Midwives place as central, the wellbeing of the woman and her baby, and locate that wellbeing within the woman’s individual social context. Framing care in this manner leads us to prioritize creating a positive experience of care, promoting and contributing to the capability of women, forging secure attachments and bonds of love, and enabling joy. It enables midwives to think and see their role as practitioners differently from other health care practitioners within the health care system. The same document goes on to describe that ‘[f]undamental to midwifery care is the understanding that a woman’s caregivers respect and support her so that she may give birth safely with power and dignity.’ (6, p.1)

Midwifery care holds a fundamental respect for the personal autonomy and dignity of the woman and her reproductive rights. It centers wellbeing, and moves away from the restrictions of risk-based medicine. While this care-through-relationship approach may appear simple, it is complex and requires a high level of knowledge in a number of fields, including not only health care but also psychology, sociology, counselling and the humanities.

Other aspects of the midwifery philosophy of care are referred to also within the scope and model of care, and will be discussed below.

5.3 Scope & Model of Practice

The specific scope of midwifery practice varies by country and jurisdiction, and is discussed in further detail in chapter 3 – Midwifery within the Health Care System. In Canada, midwives specialize in normal pregnancy, intrapartum and postpartum care, from conception to six weeks postpartum. The midwifery scope of practice reflects the internationally recognized scope of midwifery care, as defined by the ICM, which states, in part,

The midwife is recognised as a responsible and accountable professional who works in partnership with women to give the necessary support, care and advice during pregnancy, labour and the postpartum period, to conduct births on the midwife’s own responsibility and to provide care for the newborn and the infant. This care includes preventative measures, the promotion of normal birth, the detection of complications in mother and child, the accessing of medical care or other appropriate assistance and the carrying out of emergency measures. (1, p.1)

While the way midwifery is practiced in Canada varies slightly from province to province, the model of care is the same nationwide. (7,8) Midwives are autonomous, primary care providers. This means that midwives provide care on their own authority. They are the entry-point to the health care system, for the people they serve. A pregnant woman does not have to also see a doctor, or be referred to midwifery care by a physician. A woman sees their midwife or group of midwives for all pregnancy-related issues, and should also consult with them before seeing a doctor for anything non-pregnancy related. Meanwhile, midwives are able to, and should, consult directly with an appropriate physician, in the event that a woman’s care demands knowledge or speciality that is beyond the midwife’s scope.

In addition to being primary care providers, midwifery care is shaped by five basic principles: continuity of care (or carer), informed choice, community-based, choice of birth setting and evidence-informed practice. These five principles form the foundation of the midwifery model of care across the country, and together are what make midwifery care unique in the Canadian health care system.

5.3.1 Continuity of Care

A woman’s relationship with their pregnancy care providers is vitally important. Not only are these encounters the vehicle for essential lifesaving health services, but a family’s experiences with caregivers can empower and comfort, or inflict lasting damage and emotional trauma. (9) The midwifery approach starts in the relationship through which they work with women; a reciprocal partnership: getting to know and trust each other over time. This partnership is made possible by what has come to be known as ‘continuity of care’, and is arguably the most central aspect of the midwifery model of care in Canada. The Canadian Midwifery Regulators Consortium (CMRC) discusses the importance of continuity of care,

The Canadian model of care is seen as one of the most progressive in the world. All registered midwives in Canada provide continuity of care so that women and their families have the opportunity to get to know their midwife or midwives well before the baby is born, and have a familiar caregiver with them during labour and birth and for their postpartum care. (10, p.1)

A Cochrane review of continuity of midwifery care, provided by team and caseload midwife, based on 15 trials involving 17,674 women, found benefits in maternal and neonatal health outcomes with the continuity of midwifery care model. (11) When compared to women receiving medical-led or shared care, women at low and higher risk who received continuity of care from a midwife they know during the antenatal and intrapartum period are 24% less likely to experience preterm birth, 19% less likely to lose their baby before 24 weeks gestation, and 16% less likely to lose their baby at any gestation. Women with continuity of care from a midwife were also more likely to have a vaginal birth, and fewer interventions during birth. (12)

External Links

You can read the individual provincial interpretations of the model of care at the links below.

British Columbia: http://cmbc.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/11.05-Midwifery-Model-of-Practice.pdf

Ontario: http://www.cmo.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Continuity-of-Care.pdf

Quebec: http://www.osfq.org/quest-ce-quune-sage-femme/philosophie-et-normes-de-pratiques/?lang=en

External Link

You can read the Cochrane review of the continuity of midwifery here: http://www.cochrane.org/CD004667/PREG_midwife-led-continuity-models-care-compared-other-models-care-women-during-pregnancy-birth-and-early

In the same review, it was found that women who received continuity of midwifery care were more positive about their overall birth experience, with increased agency and sense of control and less anxiety. (13,12) They also reported greater satisfaction with information, advice, explanation, place and mode of birth, preparation for labour and birth, and choice for pain relief than women who received medical-led or shared care. (13)While the precise mechanisms of continuity are not completely understood, the qualitative research findings suggest these include advocacy, trust, choice, control, and a sense of being heard. (14)

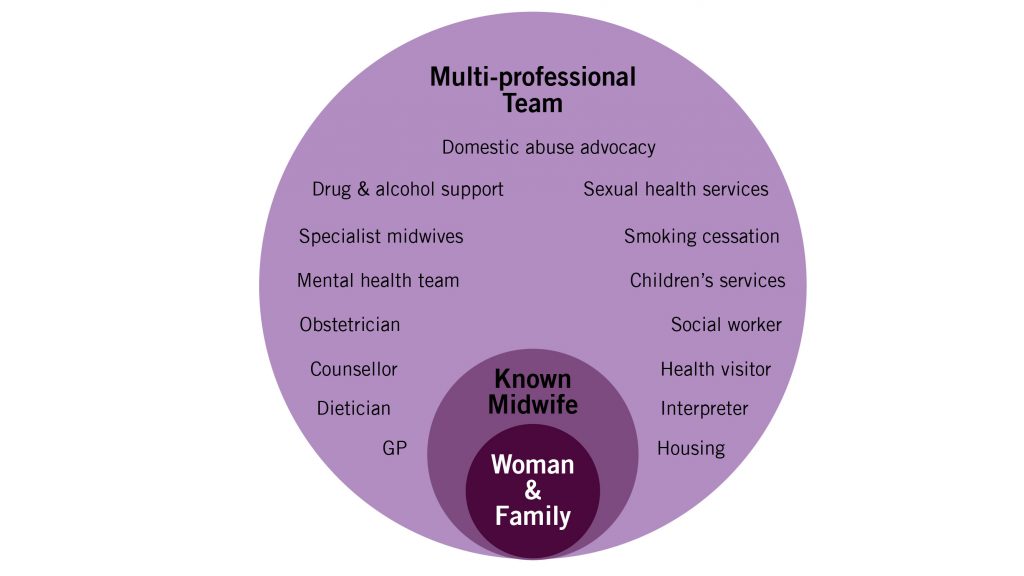

The infographic in Figure 5-1 symbolizes the woman being ‘wrapped around’ by their midwife who, when necessary, facilitates referral and consultation with other specialist services, and care that is personalized to her needs. This symbolizes the relationship with women which is at the heart of women-centred care. But it will be noted that the woman and her midwife are also ‘wrapped around’ by a number of other services and different pathways of care. This is not isolated midwifery but midwifery that connects the woman with ease to all the resources of well-developed maternity and social care.

The development of relational continuity in midwifery has illustrated the powerful effect of midwives developing a relationship with women over time, while working in systems of care that are supportive to effective practices, and being integrated in effective health services with ease of consultation, referral and appropriate intervention when necessary.

5.3.2 Informed Choice

Working in partnership with means working together to support childbearing women to make decisions about their own care. Midwives recognize the woman as the primary decision-maker for the course of her care. They support the woman’s rights to make informed choices, and support thoroughly informed decision-making by ‘providing complete, relevant, objective information in a non-authoritarian, supportive manner.’ (7, p.4) The College of Midwives of Ontario (8) meanwhile, defines informed choice as a, ‘collaborative information exchange between a midwife and her woman that supports woman decision-making.’ (p.4)

Informed decision making is a process which involves five steps for conversation and information management (15):

- Finding out what is important to the woman and their family

- Using information from the clinical examination

- Seeking and assessing evidence to inform decisions

- Talking it through

- Reflecting on outcomes feelings and consequences

Often, informed choice decision making does not result from one, time-limited conversation. It may continue over several weeks or months of a pregnancy, and be revisited during several visits with the midwife. The process should therefore be seen as a circle rather than a list. In describing this process with people who are making decisions at the end of life, Gawande (2014) talks about different levels, giving information, providing consumer choices, or interpretive conversations in which much of the care provider’s time is spent listening.

In order to do informed choice well, the woman needs to have enough time to fully explore each topic. Midwifery appointments tend to be thirty to forty-five minutes long, for most of the pregnancy. This is for the dual purpose of both supporting relationship-building between the woman, their family, and the midwifery team, and enabling informed choice decision making.

Finally, it is important to recognize that while we profess to offer choice and support women in making decisions, the agenda is ultimately set by the birthing culture in which we live and work, the services available, and the expectations created by those services. The knowledge, values, biases, language and style of the midwife and other professionals will also influence and inform interactions with the woman, and ultimately, the decisions she makes.

5.3.3 Community-based

Midwives were traditionally community-based, meaning that they were both part of, and understood, the communities and life circumstances of those they served. Community-based services still exist in many countries but have been reduced and limited in many parts of the world. In Canada, most midwives practice out of community-based (rather than hospital-based) clinics. The ability of midwives to practice independently, outside the hospital setting, creates an important conceptual (and political) separation from the medicalized model of care.

Meanwhile midwives in Canada are supported to provide their full scope of care – antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum – in the woman’s home, if the woman so chooses, and if the conditions are safe for the woman and the fetus. The midwife’s ability to provide care in the home puts the two on more equal footing. The woman is able to receive clinical care in the space she is most comfortable, and the midwife becomes a visitor in that space. This helps to decrease the power imbalance inherent in the traditional health care provider – patient relationship.

5.3.4 Choice of Birth Setting

In Canada, midwives are the only health care providers for whom offering choice of birthplace is an essential aspect of care. In some provinces, physicians have the option to provide homebirth if they so choose, however in practice very few do so. Meanwhile, where midwifery is regulated, midwives must be willing and able to provide care in any setting, including home or hospital, and in about half the provinces, birth centres, where available. (16) Evidence demonstrates that these are all options which give women and babies who require straightforward care, a safe environment for care and for birth, reducing the risk of unnecessary interventions and ensuring continuity of care. (17)

The ability to provide choice of birth place is key to the midwifery model of care, as it is intrinsically linked to informed choice, and to the principle of providing true woman-centered care, which focuses on the needs and desires of the childbearing woman and her (self-defined) family. Midwives provide information needed for the woman to make an informed choice about the appropriate setting for her, in which to give birth. Because the midwife is able to provide evidence-informed care in any setting, the woman is then free to make that decision based on her own needs and vision for her birth.

The availability of options where midwives may practice fully, be they at home, in birth centres or in midwifery-supportive maternity care units in hospitals, has helped move midwifery and the re-development of midwifery skills and knowledge forward. Systems and protocols for consultation and referral and respectful relationships with other professionals and birth workers are essential components of safety in this regard. The development of the appropriate care pathway, including the provision of different places of birth, is critical to effective midwifery.

5.3.5 Evidence-informed Practice

Finally, midwives are committed to evidence-informed practice. Evidence-informed practice uses evidence to identify the potential benefits and risks of any clinical decision. This means that that midwives must commit to continually developing and sharing midwifery knowledge. They must attend continuing education opportunities in the field of midwifery and obstetrics, and related topics and must keep their knowledge current about emerging practice guidelines and the research that supports them. You can read more about this in chapter 12 – Midwives Using Research.

Importantly, clinical research, while critical, is only one source of evidence which midwives must be aware of and able to discuss with women. When practice is truly evidence-informed, other factors, including health care resources, the individual clinical state and circumstances, the clinician’s own expertise and experience, availability of appropriate resources and the woman’s own preferences are also considered. The midwife’s clinical expertise ties them all together to inform practice decisions, and in support of informed choice decision making. (18)

Midwives in Canada are autonomous, primary care providers. As health care systems are provincially regulated, there are slight variations in how midwifery is practiced from province to province, however the scope of practice is consistent: normal pregnancy, intrapartum and postpartum care, from conception to six weeks postpartum. Evidence-informed practice, choice of birth setting, community based, informed choice and continuity of care are the five main principles which form the foundation of the Canadian midwifery model of care. Each of these aspects contributes to a unique model of care where childbearing women and their families, their social contexts and preferences for care, are held at the centre. Midwives are called to meet women where they are at, to build trusting relationships, and to provide care that supports normal, physiologic birth with as few interventions as necessary.

5.4 The Art & Science of Midwifery Care –Specialized Skills of the Midwife

Working within the midwifery model of care requires several skills and skill sets. As clinicians, many of the midwife’s skills overlap with our nursing and physician colleagues. However, the emphasis in our model on relationship building and the provision of informed choice, as well as the midwife’s focus on pregnancy and birth as normal physiological processes, demands that midwives take up the role not only of clinicians, but also of educators, companions and promotors of health and well-being. The combination of skills required to fulfil these multiple roles provides a unique bridge between the science of medicine, and the art of individualized care provision. The midwife is called to move between these skill sets with ease and fluidity.

5.4.1 Clinicians

As primary health care providers, it goes without saying that midwives must be proficient in many skills which are related to supporting normal birth and avoiding unnecessary intervention. These include (but are certainly not limited to), an understanding of and ability to support physiological birth, giving information to women and their families, increasing confidence, comfort and mobility in labour, enabling birth in an out of hospital setting, the use of water in labour, avoiding continuous electronic fetal monitoring, assessing carefully to know when intervention is required. (19,20)

Midwives must also understand the importance of knowing how and when to consult, refer, and transfer care, in a timely and efficient manner. In this regard, the ability to develop and maintain good working relationships with interprofessional colleagues, is a critical, though often undervalued skill for midwives, as with all health care providers.

Midwifery practice requires proficiency in a wide range of hands-on clinical skills including those related to assessment, intervention, diagnosis, referral and emergency skills. Importantly, the wisdom and art of midwifery come in the midwife’s ability to perform the necessary hands-on skills, while at the same time listening, watching, sensing what is happening, reading nonverbal language, and anticipating the needs of the woman and family. In this way, technical skills are woven into intentional conversations, listening, creating a suitable physical environment (e.g. dark and quiet room for labour and birth, or a space that encourages movement). Midwifery weaves these together in a way that respectfully meets the needs and as much as possible, the preferences, of women, babies and families in their individual contexts.

All of these clinical skills are outlined by the CMRC. The Canadian Competencies for Midwives document lists the specific knowledge and skills expected of an entry-level midwife generally in Canada, noting that there may be slight variation in practice form province to province. (21)

5.4.2 Educators

Whether this is forming groups, providing information sessions, or individualized discussions leading to informed choice decision-making, midwives must be able to identify what a childbearing woman needs to know, translate clinical evidence into accessible language, and support her to make strong, informed decisions. The intention of midwifery is to support the capability of the woman and her family to care for themselves and the baby. Flexible, individualized education is a critical means towards that end. (22)

5.4.3 Companions – ‘Being with’ Each & Every Woman

As discussed above, midwife means literally, ‘being with the woman’ – a companion on the journey to through pregnancy, labour and birth, and through the immediate postpartum. ‘Being with’ implies support, giving and helping the woman understand information, helping lay out the decisions to be made (e.g. induction for postdates labour or place of birth), giving confidence, while also being honest about situations. Underlying all of this is compassion and understanding of the woman’s situation and life circumstances. Midwives need to be educated and skilled, but also compassionate and responsive to multiple social contexts.

A focus on the needs of each individual may help illustrate how we might use this midwifery approach in practice. Think about the universal needs of each woman, their baby, the partner or other parent, and family. The woman needs a midwife who understands the profound importance of pregnancy, birth and the early weeks of life. Each woman will have different levels of understanding, as well as different cultural needs, support needs, preferences, desires, hopes, and worries. It is critical that the midwife get to know the woman and her family by listening and responding to them with respect and compassion for their particular life circumstances.

In a way, this reflects what the parents will be required to do: to know, understand and respond sensitively to the needs of their baby. The midwife may be seen as modelling this interaction in her relationship with the woman. Ideally each person is also supported beyond this relationship. The woman is supported by their family, their community, and health services that support their health, medical, social and psychological needs while providing genuine choices. The midwife, in turn, is supported not only by their family and friends, but also critically by colleagues and systems of care that enable the full scope of practice, and continuous improvement of knowledge, wisdom and skills. It is also far simpler to take this approach when there is continuity of the midwife-woman relationship; although even where care is fragmented some elements may be maintained. The crux of this midwifery approach is to understand that care mediated through relationship is fundamental.

5.4.4 Promotors of Health & Wellbeing

Wellbeing includes physical health as well as emotional wellbeing and a sense of security, hope and optimism. Optimal health is the best health for each individual, in their individual context, and given their individual health care needs. What makes this a more complex concept in maternity care is the balance between the woman’s health and that of the baby. Holding both of these in mind, not placing the health of one over the other, is critical in considering the appropriateness of interventions to maintain optional health in maternity care. Midwives do this by supporting physiological processes, whenever possible, while keeping in mind the overall context and preferences of each individual woman and case.

Central to midwifery practice is that we recognize the need to support normal human physiology by helping women to have a normal birth, and supporting them so that they can, if possible, avoid the use of unnecessary interventions (e.g. epidural for pain relief, or the use of artificial oxytocin to induce labour). Meanwhile, if these interventions are needed (or desired), then the midwife’s role becomes to support the woman to have the best birth experience possible for them: physiologically, but also emotionally.

Both ‘being with’ the woman, and pursuing the aim of optimal health and wellbeing require a balance of ensuring women are aware of all the possibilities for care and place of birth, including the evidence supporting each of their options and the risks associated with them. An understanding of the woman’s current health status, their values and preferences and life circumstances are critical for optimal health. This demands a unique mix of empathy, compassion, listening, understanding, and availability.

5.5 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have summarized the unique approach of midwives and midwifery practice within the Canadian health care system. The midwifery model of care is based on the five key principles of continuity of care, informed choice, community-based, choice of birth setting and evidence-informed practice. This model takes us beyond a medicalized approach to pregnancy, birth and postpartum, towards individualized, humanized care. Midwives are concerned not only with concrete clinical outcomes relating to mortality and morbidity, but also health and wellbeing, maternal capability, secure attachment between mother and baby, and family integrity. Midwives who are educated, skilled and compassionate, who work in effective health services with adequate resources, are critical in the movement towards humanized, woman-centred care for childbearing families in this country.

Importantly, the midwifery approach represents a new paradigm: we are learning as individuals and as a profession to see, think and practice differently; to move away from childbirth as an illness to be managed and towards a holistic, humanized perspective of the childbearing experience. Humanistic midwifery care requires exquisite communication skills, clinical judgement, diagnosis and decision making, manual skills, and the ability to understand as well as judge the validity of evidence, all while being in partnership with the childbearing woman, keeping her at the centre of care, and promoting optimal health and wellbeing. An ability to move seamlessly between all of the various skill sets, holding each as important as the other, is the art of midwifery practice.

References

- ICM International Definition of the Midwife [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 26]. Available from: http://internationalmidwives.org/who-we-are/policy-and-practice/icm-international-definition-of-the-midwife

- The Lancet. Maternal Health: An Executive Summary for the Lancet’s Series. Lancet. 2016;388(10056, 10057).

- Bourgeault IL, Canadian Electronic Library. Push! : the struggle for midwifery in Ontario. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press; 2006. 346 p.

- Canadian Association of Midwives. Midwifery Across Canada [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Sep 12]. Available from: https://canadianmidwives.org/midwifery-across-canada/

- Stoll K, Hall W. Vicarious birth experiences and childbirth fear: does it matter how young canadian women learn about birth? J Perinat Educ [Internet]. 2013;22(4):226–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24868135%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4010856

- College of Midwives of British Columbia. Philosophy of Care. Vancouver; 1997.

- College of Midwives of British Columbia. Midwifery Model of Practice [Internet]. Vancouver; 2013. Available from: http://cmbc.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/11.05-Midwifery-Model-of-Practice.pdf

- Ontario C of M of. The Ontario Midwifery Model of Care [Internet]. Toronto; 2013. Available from: http://www.cmo.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/The-Ontario-Midwifery-Model-of-Care.pdf

- White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. Washington, D.C.; 2011.

- Canadian Midwifery Regulators Council. Midwifery in Canada [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 12]. Available from: http://cmrc-ccosf.ca/midwifery-canada#model

- Smith V, Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Pract Midwife [Internet]. 2013;16(10):39–40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24371917%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23963739

- Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. In: Sandall J, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2017 Aug 1]. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5

- McLachlan HL, Forster DA, Davey MA, Farrell T, Flood M, Shafiei T, et al. The effect of primary midwife-led care on women’s experience of childbirth: Results from the COSMOS randomised controlled trial. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(3):465–74.

- Sandall J, Coxon K, Mackintosh N, Rayment-Jones H, Locock L, Page L. Relationships: the pathway to safe, high-quality maternity care [Internet]. Oxford; 2015. Available from: https://www.gtc.ox.ac.uk/images/stories/academic/skp_report.pdf

- Page LA, Mccandlish R, editors. Being with Jane in Childbirth: putting science and sensitivity into practice. In: The New Midwifery: Science and Sensitivity in Practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2006. p. 359–77.

- Canadian Women’s Health Network. Homebirth [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2017 Sep 12]. p. 1. Available from: http://www.cwhn.ca/en/yourhealth/faqs/homebirth

- Janssen PA, Saxell L, Page LA, Klein MC, Liston RM, Lee SK. Outcomes of planned home birth with registered midwife versus planned hospital birth with midwife or physician. CMAJ. 2009;181(6–7):377–83.

- Health Science Centre Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Evidence-Informed Practice Resource Package [Internet]. Winnipeg; 2010. Available from: http://www.wrha.mb.ca/osd/files/EIPResourcePkg.pdf

- Simkin P, Hanson L, Anchetta R. The Labor Progress Handbook: Early Interventions to Prevent and Treat Dystocia. 4th ed. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. 408 p.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies | Guidance and guidelines | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2014 [cited 2017 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/chapter/Recommendations#place-of-birth

- Consortium CMR. Canadian Competencies for Midwives [Internet]. Winnipeg; 2008. Available from: http://cmrc-ccosf.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/National_Competencies_ENG_rev08.pdf

- Leap N, Hunter B. Supporting Women for Labor and Birth a Thoughful Guide. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge; 2016. 254 p.

Long descriptions

A diagram with three concentric circles. The center circle is labelled ‘woman and family.’ The larger circle that envelopes that is labelled ‘known midwife.’ The largest, outermost circle is labelled ‘multi-professional team’ and contains the description of those team members: domestic abuse advocacy, sexual health services, smoking cessation, children’s services, social worker, health visitor, interpreter, housing, GP, dietician, counsellor, obstetrician, mental health team, specialist midwives, drug and alcohol support. [Return to Figure 5-1]