8 Health Policy Analysis in Midwifery

Cristina Mattison, MSc, PhD(c)

Change in the health care system may be met with a mix of eagerness or resistance by members of the public, health care professionals, governments or other stakeholders. For example, introducing midwifery care into health systems in Canada was a long-awaited and welcome change for many but a change that was resisted by others, and was received differently in various jurisdictions. In each case, changes were effected by new policies that were put in place.

In the broadest sense, policy informs action as a result of decision-making through various inputs. Policies are used across settings and institutions. Policies made at governmental levels (e.g. legislation) are the most visible, but policies have a large role in institutions (e.g. hospitals) and organizations (e.g. clinical guidelines or administrative policies from professional associations).

In this chapter we examine how health care policies are defined and look most closely at the processes involved in setting the government’s agenda and in formulating new policies. This chapter introduces you to core health policy analytic frameworks, and how they are applied in the context of midwifery. In your role as a health care professional, it is important that you understand how health care policies are made, and are also able to evaluate policies, and potentially, inform policymaking.

4.1 Policy Cycle

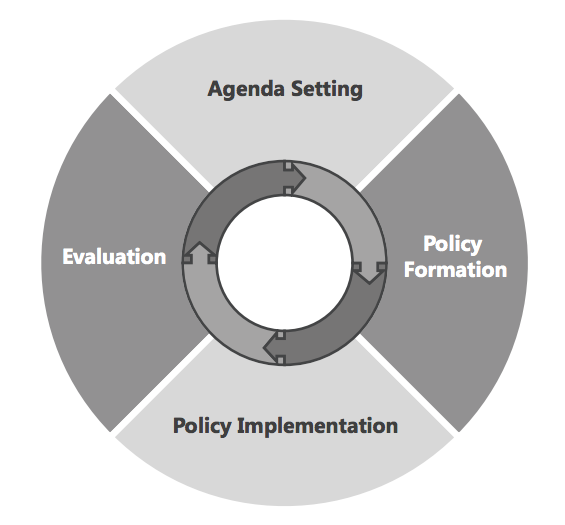

While we often think that policymaking is a straightforward rational process, it can be messy and, most often is not clear-cut. The policy cycle, originally developed by Lasswell (1951), is a helpful lens through which to distinguish various phases of the policy process. (1) The theory is often referred to as the stages model and consists of four main components:

- Agenda setting

- Policy formulation

- Policy implementation

- Evaluation

This chapter will explore the agenda setting stage in most detail, since knowledge of how to get issues on to the government’s agenda is important for health care professionals with interests in informing policy or creating policy change. The other stages will be discussed more briefly.

The development of the policy cycle was central to establishing the field of health policy analysis. The cycle separates the policy process into distinct components and allows for analyses of individual stages (Figure 4-1). Once a problem is defined , an agenda is set and the process moves to the policy formulation stage. In this phase, policy solutions are presented and evaluated. Solutions that are both technically feasible, and that take into account the arrangement of the health system in which they will be proposed, frequently have greater success in the policy formulation process. An example of such a solution was the introduction of two new birth centres in Ontario, Canada. The reform aligned with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s efforts to move services out of hospitals and into community-based settings. (2) Once a policy has been formulated, it must be implemented. The process of policy implementation can face a number of challenges, and this is particularly the case if the formulated policy does not align with the intended goals, which often results when trying to satisfy multiple, competing interests. The final stage of the cycle is evaluation, which may include a formal evaluation of policy outcomes. Evaluations may be based on outputs, such as number of births, or may assess processes such as a program evaluation of the new birth centres in Ontario. The results of the evaluation could lead to a new or revised policy agenda or new policies, which are also then implemented and evaluated.

4.1.1 Agenda Setting

Agenda setting is the first stage in the policy cycle. The agenda setting framework, as laid out by Kingdon (2011), recognizes the complexity of the public policymaking process and explains in detail the process by which items move from the governmental agenda (i.e. topics that are receiving interest) to the decision agenda (i.e. topics up for active decision). (3) Policymakers face many time and resource constraints that limit their ability to deal with all the topics. Given all the potential topics that policymakers could pay attention to, the framework explores how and why policy issues either rise or fall away from the government’s agenda. The framework consists of three streams: problems, policies and politics (Table 4-1).

| Table 4-1. Kingdon’s agenda setting framework – the three streams (3,4) | ||

| PROBLEM Attention to problems through: |

POLICY Generation of policy proposals through: |

POLITICS Political events consist of: |

| Focusing events (crisis or disaster) |

Dispersion of ideas in a policy area (a policy proposal circulates and is revised; in the end, some ideas come forward while others do not) |

Shifts in national mood (includes changes in the political climate, public opinion and/or social movements) |

| Change in an indicator (e.g. increasing cesarean rates or the rising cost of healthcare) |

Communication / persuasion (items that are more interesting or novel) |

Shifts in the balance of organized forces (e.g. interest group pressure campaigns) |

| Feedback from existing programs (feedback specific to a problem on a program that is not operating or performing as intended) |

Feedback from existing programs (feedback specific to policy on a program) |

Events within government (e.g. elections, turnover in government, jurisdictional disputes) |

4.1.1.1 Problem Stream

This stream is made up of three components:

- focusing events, which can be a crisis or a disaster that receives media attention;

- a change in indicator such as cesarean rates or the rising cost of healthcare; and

- feedback from existing programs.

Examples of how the midwifery organization can highlight the problems stream to support their aims include:

- using a focusing event that pertains to scope of practice and is receiving active media coverage to call attention to the problem;

- using peer-reviewed literature to support that midwives are a cost effective option in low-risk maternity care, linking to a change in indicator; and

- collecting feedback from a current obstetric program that is not operating as it should and where a midwifery program with the appropriate scope of practice can present a suitable solution.

4.1.1.2 Policy Stream

This stream consists of diffusion of ideas in a policy area (i.e. natural selection), communication and/or persuasion, and feedback from current programs. These factors can lead to the generation of policy proposals, as those that are technically feasible, fit with dominant values, and are acceptable given future constraints are more likely to be considered. The midwifery organization can align itself with a government’s health system reforms, like the example of health system reform in Ontario that emphasizes client-centred care by moving services out of hospitals into community-based clinics. (5)

External Link

Read the original press release for birth centres in Ontario here: http://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2014/01/midwife-led-birth-centre-opens-in-toronto.html

4.1.1.3 Politics Stream

This includes changes in national mood and in the balance of organized forces (e.g. interest group pressure campaigns), as well as events within government (e.g. elections). Factors in this stream are more likely to rise higher on the agenda if they are congruent with national mood, have interest group support, lack interest group opposition, and align with the governing party. A midwifery organization can take advantage of the politics stream by having significant public support and strong centralized interest groups, while aligning with the political climate (e.g. values of the dominant political party).

What and who influences the agenda? The governmental agenda is influenced by the problems or politics stream as well as visible participants, while the decision agenda is influenced by a coupling of all three streams into a single package. A policy window is opened by the appearance of a compelling problem, like a focusing or a political event, such as an election. A midwifery organization that wishes to increase the chances of moving an item of midwifery scope of practice legislation onto the decision agenda may be wise to consider enlisting the help of a policy entrepreneur. This is a person who is capable of, and prepared to, take immediate action to push the issue forward once the window presents itself. Failure to couple the problem, policies and politics streams will result in the policy window closing before progress can be made.

Exploring the agenda setting process is a helpful to understand how items reach the government’s agenda and then either rise or fall away from the decision agenda. A last word on agenda setting; discerning what items are on the government’s agenda is not always straightforward. Government communications, like budgets, speeches and announcements, are often good indicators. However, neither will give a complete picture as some agenda items will remain relatively hidden from public view at any given time and the media is selective in what it reports.

A fourth ‘P’ may also need to be considered: Participants, some of whom may be hidden and others who are highly visible. Policy entrepreneurs are a special type of participant in that they can either be a visible or hidden participant and are not restricted to politicians. They also possess certain characteristics: they must have expertise on the issue, hold power in terms of political connections and they must be tenacious. Timing is a critical factor and therefore a policy entrepreneur must not only have the skills, but also the patience to take advantage of a policy opportunity when one presents itself.

Did You Know?

Although academics are generally considered hidden participants, if they make use of the media to discuss their findings or solutions for an issue, they could be considered visible participants.

Using Kingdon’s (2011) multiple stream framework, suppose a midwifery organization wants to change the scope of practice legislation for the profession, it could use the following to influence policymaking (3):

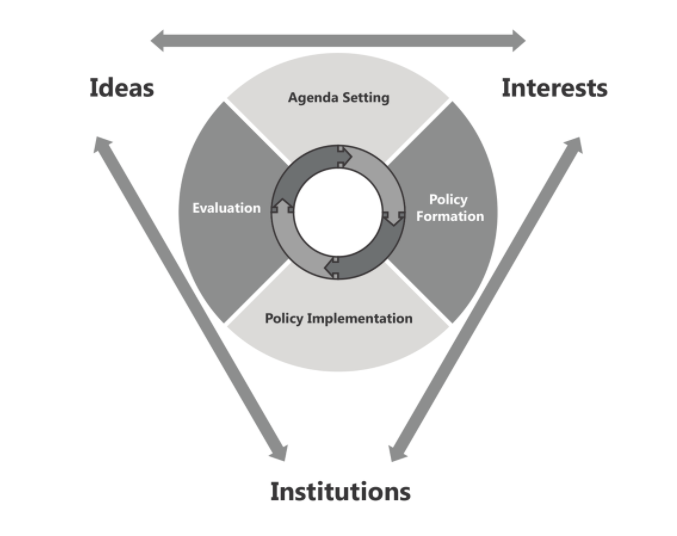

4.2 3i Framework

The policy cycle is helpful in identifying and separating the policy process into segments. Complementary to the policy cycle is a theoretical framework, called the 3i framework, which takes account of forces that can shape and influence policies in a complex interplay of institutions, interests and ideas (Figure 4-2). (4) In this framework, institutions include government structures (e.g. federal vs. unitary government), policy legacies (e.g. the role of past policies) and policy networks (e.g. relationships between actors around a policy issue); interests can include a range of actors; and, ideas relate to peoples’ beliefs and values. The last element of the framework are external factors and includes releases of major reports (e.g. United Nations Population Fund’s 2014 State of the World’s Midwifery Report) or political, economic or technological changes.

Did You Know?

There are fourteen health care systems in Canada; there are ten provincial health systems, three territorial health systems and one federal health system. Each province/territory has responsibility for its own health system. The federal government’s arms-length role is less visible, and mostly limited to financial contributions, such as transfer payments, and care for specific populations such as First Nations peoples living on reserve and Inuit, serving members of the Canadian Armed Forces and eligible veterans. (6)

External Link

The United Nations Population Fund’s 2014 State of the World’s Midwifery Report can be found here: http://www.unfpa.org/sowmy

4.2.1 Institutions

The 3i framework divides institutions into three categories: government structures, policy legacies and policy networks. The interplay of these components can be studied by competitive analysis to show the importance of the influence institutions have in the political process. (7)

Historical institutionalism is the method most often used for this type of analysis and is grounded on the concepts of path dependence and policy legacies. (8) These concepts explain how past decisions serve to influence and constrain the decisions or policies that are possible today. (9) The timing and sequencing of events are crucial elements in path dependence, such that seemingly small events may produce large outcomes by setting in motion a particular course of action. (10) We can apply this approach to understand the barriers and facilitators to midwifery legislation that occurred in two Canadian provinces, Ontario and Québec. While these are neighbouring provinces, there have very different midwifery regulations. In Ontario, a window of opportunity was created by the Health Professions Legislation Review (1983), and midwifery-related interest groups were able to take advantage of it in order to formalize the profession. (11) By comparison, institutions constrained the legislative process in Québec since it was the only province to experiment with midwifery practice options, through a pilot project, before legislation. (12) This example will be used to illustrate the following sections.

4.2.2 Interests

The 3i framework addresses the role of interest groups and the extent to which they influence and impact the policymaking process, examining particular groups of people such as societal interest groups, elected officials, public servants, researchers, and policy entrepreneurs. (4) Some argue that interest groups play a critical role in the political process and are powerful and central to the policy process and outcomes. (13) Continuing with the example of midwifery regulation in Québec, strong interest groups influenced the policy process. Piloting midwifery before legislation was recognized as a compromise to appease significant physician interest group opposition. (14) A broader analysis of health policy shows that separation between interest groups and government policymaking is becoming increasingly difficult. (15) Research on the role of the pharmaceutical industry in health policymaking has shown the significant political power that this interest group can exert, particularly in the United States and the example of human papillomavirus vaccination policies. (15)

4.2.3 Ideas

Traditionally, ideas have been thought to be of lesser influence when compared to institutions or interests. (16) This is because ideas are complex and we know much more about what ideas are than we know about how they work. (17) The 3i framework breaks down ideas into knowledge or beliefs about ‘what is’, values about ‘what ought to be’ and also combines the two. (4) In the example of the regulatory legislation of midwifery in Canadian provinces, the ideas of feminism provided a strong ideological framework that helped midwifery gain critical support to become regulated in Ontario in 1994. (18)Evolving ideas related to feminism and strong government champions in the Ministry of Health, who acted as the carriers of ideas, helped to move midwifery forward in the province.

4.2.4 External Factors

Interacting with the 3i framework are factors that are external to the policy community yet still have an influence on institutions, interests and ideas. These include events such as the release of major reports (e.g. reports from the Auditor General), media coverage, a disease outbreak (e.g. Zika virus), political (e.g. election), economic (e.g. recession), or technological change (e.g. electronic health records). (4)

4.2.5 Applying the 3i Framework to Midwifery

The 3i framework brings together major political science scholarship to create a useful format to examine policy choices. The framework can be applied to midwifery broadly, such as happened during the process to regulate midwifery in a particular jurisdiction, or to a specific policy issue, such as creating a birth centre. Table 1-2 uses the 3i framework to illustrate the important influences on the decision to implement regulated midwifery in Ontario.

Analyzing institutional factors highlights the importance of the timing and sequencing of events, and shows how past policy choices, such as capping midwifery education seats, creates legacies that are not only set in motion, but may also limit the scope of future action.

Interest groups, such as midwifery associations, can champion a policy, while interest group opposition can present barriers.

Ideas, particularly values and beliefs, are also influential. In midwifery, women-centred care and feminist ideologies have helped the profession gain critical support. (18,19)

| Table 4-2. 3i case study of midwifery in Ontario, Canada (6, 20) | ||

| Institutions

|

POLICY LEGACIES | EXTERNAL LINKS |

British North America Act, 1867

|

British North America Act http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/constitution/lawreg-loireg/p1t11.html |

|

Canada Health Act, 1984

|

Canada Health Act http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/fulltext.html |

|

Midwifery Act, 1991

|

Midwifery Act https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/91m31 |

|

Government structures

|

Ontario Liberal Party http://www.ontarioliberal.ca |

|

Policy networks

|

||

| Interests | Overview of midwifery related interest groups:

|

Association of Ontario Midwives http://www.aom.on.ca Canadian Association of Midwives http://www.canadianmidwives.orgOntario Hospital Association http://www.oha.com/Pages/Default.aspxConsumers Supporting Midwifery Care http://www.midwiferyconsumers.org |

| Ideas | Values

|

|

Knowledge

|

Cochrane systemic review http://www.cochrane.org/CD004667/PREG_midwife-led-continuity-models-care-compared-other-models-care-women-during-pregnancy-birth-and-early |

|

| External factors |

|

Action Plan for Health Care http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/ms/ecfa/healthy_change/ Ontario Birth Centre Announcement https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2014/1/midwife-led-birth-centre-opens-in-toronto.html |

4.3 Key Points Summary

- The process through which policies are created is complex.

- As health care professionals, midwives need to have an understanding of health policy analytic frameworks to evaluate health care decisions, and of the concepts needed to inform policymaking.

- Applying the core concepts of health policy making to your own health system provides a deeper understanding of the policies in place as well as the policy options available in your jurisdiction.

- The policy cycle consists of four components: agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and evaluation.

- Agenda setting explains how issues get on the government’s agenda, and examines the factors that cause the issue to either rise up, or fall away from, the decision agenda.

- The 3i framework shows how institutions (e.g. policy legacies) shape the policy options available, while interest groups can help to mobilize (or hinder mobilization) around a policy issue, and that ideas (beliefs and values) of the public and political elites are a key consideration.

References

- Lasswell H. The Policy Orientation. The Policy Sciences. 1951. 3-15 p.

- Mattison CA. Introducing Midwifery-led Birth Centres to Ontario [Internet]. Health Reform Observer – Observatoire des Réformes de Santé. 2015. Available from: https://escarpmentpress.org/hro-ors/article/view/559

- Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers; 2011. 304 p.

- Lavis J. Studying health-care reforms. In: Lazar H, Lavis J, Forest P, Church J, editors. Paradigm freeze: why it is so hard to reform health care in Canada. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2013.

- Ministry of Health and Long-term care. Midwife-Led Birth Centre Opens in Toronto. Ontario offering more childbirth options for expecting mothers. [Internet]. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2014. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2014/01/midwife-led-birth-centre-opens-in-toronto.html

- Lavis J, Mattison C. Introduction and overview. In: Lavis J, editor. Ontario’s health system: Key insights for engaged citizens, professionals and policymakers. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum; 2016. p. 15–43.

- Immergut EM. The rules of the game: The logic of health policy-making in France, Switzerland, and Sweden. Struct Polit Hist institutionalism Comp Anal. 1992;4(4):57–89.

- Hall PA, Taylor RC. Political science and the three institutionalisms. Polit Stud. 1996;XLIV:936–57.

- Pierson P. When Effect Becomes Cause: Policy Feedback and Political Change. World Polit. 1993;45(4):595–628.

- Pierson P. Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. American Political Science Review. 2000. p. 251–67.

- Bourgeault IL, Canadian Electronic Library. Push! : the struggle for midwifery in Ontario. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press; 2006. 346 p.

- Bourgeault I, Benoit C, Davis-Floyd R. Reconceiving midwifery. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2004. 352 p.

- SMITH MJ. Pluralism, Reformed Pluralism and Neopluralism: the Role of Pressure Groups in Policy???Making. Polit Stud. 1990;38(2):302–22.

- Vadeboncoeur H. Delaying: legislation the Quebec experiment. In: Bourgeault I, Benoit C, Davis-Floyd R, editors. Reconceiving midwifery. McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2004.

- Mello MM, Abiola S, Colgrove J. Pharmaceutical companies’ role in state vaccination policymaking: The case of human papillomavirus vaccination. American Journal of Public Health. 2012. p. 893–8.

- Bhatia VD, Coleman W. Ideas and Discourse: Reform and Resistance in the Canadian and German Health Systems. Can J Polit Sci. 2003;36(4):715–39.

- Jacobs AM. How Do Ideas Matter?: Mental Models and Attention in German Pension Politics. Comp Polit Stud [Internet]. 2008;42(2):252–79. Available from: http://cps.sagepub.com/content/42/2/252.short

- TL A, IL B. Feminism and women’s health professions in Ontario. Women Health [Internet]. 2003;38(4):73–90. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=106758722&site=ehost-live

- Benoit C, Wrede S, Bourgeault I, Sandall J, De Vries R, van Teijlingen ER. Understanding the social organisation of maternity care systems: midwifery as a touchstone. Sociol Health Illn [Internet]. 2005;27(6):722–37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16283896

- Government of Canada. Canada Health Act: R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6 [Internet]. Justice Laws Website. 2014. Available from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-6/page-1.html

Long Descriptions

A diagram of the policy cycle. A circle is split into four equal parts. The top quarter of the circle is labelled Agenda Setting. Moving clockwise, the next quarter to the right is labelled Policy Formation. The bottom quarter is labelled Policy Implementation. The last quarter on the left is labelled Evaluation. Arrows in the center of the circle indicate that this process flows from one quarter to another, clockwise, starting with Agenda Setting, then Policy Formation, then Policy Implementation, then Evaluation. Evaluation flows back into Agenda Setting. [Return to Figure 4-1]

The policy cycle, this time also showing the external factors that can influence policy – ideas, interests, and institutions, which are written outside the policy cycle. Arrows show that each of these three external factors can influence not only the policy cycle, but also each other. [Return to Figure 4-2]