5 Birth & its Meanings: Representations of Birth in Art

Elaine Carty, MSN, CNM, DSc (hc), CM

Each second, approximately 4.3 births occur throughout the world. Some births bring happiness, others sadness. Many are wanted, many unwanted. Most babies are born into poverty, a few into wealth. Whatever the circumstances, those giving birth know and feel its importance. Those who observe birth, whether they are a midwife, sage-femme, birth attendant, partner, friend, family or stranger, know they have been part of a process that ensures our species continuing existence and exemplifies human essence.

Being born is important

You who have stood at the bedposts

And seen a mother on her high harvest day,

The day of the most golden of harvest moons for her.You who have seen the new wet child

Dried behind the ears,

Swaddled in soft fresh garment,

Pursing its lips and sending a groping mouth

Toward nipples where white milk is ready.You who have seen loves payday

Of wild tolling and sweet agonizing.You know being born is important

You know that nothing else was ever so important to you

You understand that the payday of love is so old,

So involved, so traced with the circles of the moon,

So cunning with the secrets of the salts of the blood

It must be older than the moon, older than salt.Being Born Is Important

Carl Sandburg (2)

Birth has been represented by human beings since pre-historic times in poetry, prose, drawing, painting, sculpture, film, video, photography, theatre, textiles, social media, music and every other human expression imaginable. Through each such representation we attempt to convey and discern meaning. Midwives and midwifery students can learn a great deal about birth’s meanings around the world by engaging with the many human creative expressions around birth that they will encounter. It is very important to be aware that each person’s unique perspective influences how they respond to representations around childbirth and how they attribute meaning. These differing perspectives influence the writer, artist, or photographer who produces artifacts as well as those who see the work. Barbara Bolt in her book Art Beyond Representation reminds us that the act of making the work is performative and that aspect must be considered in addition to the finished work. (3) Burton in her book Natal Signs, examines the framework of Michel de Certau and points out that the border separating production and consumption is porous; the consumer of any work is inevitably engaged in a form of secondary production. (4) As midwives, we must be aware that our unique interpretations are passed on to our clients, our communities and ultimately to our policy makers.

When engaging with representations of childbirth, it is vital to consider not just the content of the work but also how it is used and for what purpose. Is art political? This debate has existed in the art world for a very long time. If being political means engaging with power and power relationships – whether that is the interaction between subjects in the work, between artist and subject, between artist and artist – then yes all art is political. Power is embedded in the everyday; the way everything in society works. It is imperative to examine how representations question power relations, ‘unsettle assumptions, and break boundaries.’ (4) The more work done in trying to understand perspectives of those who write about childbirth from a personal, historical or anthropological framework, make art or poetry, the better midwives will be able to be ‘with woman.’

Nonetheless, no one can ‘know’ how others have or will experience childbirth. So how can a student of midwifery, in this time, in this place, understand the complex intersection of physiology and culture? How can anyone contemplate what childbirth was like 4000 years ago in Mesopotamia or even what it means to the woman seeking midwifery care today?

This chapter will provide an opportunity to engage with representations of birth and its meaning. In observing works, many art historians emphasize the relationship between the aesthetic, the sensory or emotional values elicited, as well as the intention or reading of the work. To be present when looking and/or listening to representations of childbirth, involves asking questions about the work that explore these relationships. In each of the following sections, there are a number of questions to help you reflect on the included representations. A work may make us stop, look or listen carefully, feel moved, experience joy or sadness. We may be able to say we like or dislike a piece of art or poem or comic and yet be unsure why that is so. Often, we need to look at an art piece several times or reflect on a work of fiction or poetry over time before we understand our reaction to it.

1.1 Representations of Birth Throughout History

Although pregnancy, birth and motherhood/parenthood have been topics of discussion and representation by humans for thousands of years, this section will discuss four particular periods in history that illustrated the importance and meaning of birth in their time in quite different ways.

Reflect

Throughout this chapter, there are several examples of artworks that represent birth and parenthood. When they appear, ask yourself the following questions:

What is my first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in my practice? (5)

1.1.1 Early Representations of Fertility & Birth

We have evidence that species of early humans were creating two and three-dimensional images 40,000 years ago. (5) Cave paintings of animals and human hands dating to 35,000BCE have been found on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. Who painted them, their feelings, thoughts associated with the work, why they were painted, and the meanings they had at the time are all lost to history. However, meaning becomes somewhat clearer when we observe three-dimensional sculptures that appear to represent fertility and birth. ‘Venus figurines’ is a term used to describe small, between two and eight inches (5-20cm), sculptures of women. Although sculpted during the pre-historic period, the term Venus was more recently applied by archeologists to reflect Venus, the Roman goddess of beauty. These sculptures are usually similar in size, appearing fully fleshed with large bellies and breasts, and little facial detail. Archeologists debate whether these small sculptures represent fertility or are a religious symbol of the time. (6)

One of the most famous of these is the Venus of Willendorf, or Woman of Willendorf, named for the Austrian town in which it was discovered in 1908 (Figure 1-1). The 11 cm high statuette is estimated to have been made between 24,000 and 22,000 BCE. She is compelling because of her large size, which would be called obese today. It is postulated by many that her voluptuousness implies fertility.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Venus_von_Willendorf_01.jpg

Did You Know?

The creation of figurines in a female form pre-dates the Roman goddess Venus by over twenty thousand years, although in modern times many of these figurines are commonly referred to as Venus.

Another form of artistic representations of fertility and birth is found in early rugs from Turkey, Kurdish rugs, Qashqai, Lori, and Shah Savan rugs of Iran and the Balusch and Turkoman rugs of Central Asia. All have a motif that has been described as a fertility/birth symbol, a simplified graphic design of a pregnant female, symbolizing a veneration of birth and generation of life. (7) There are many symbols from many traditions that symbolize fertility and childbirth in rugs and textiles, and just as many textile specialists who say it is difficult to interpret the meaning of symbols developed thousands of years ago. Nonetheless the fertility/birth symbol in textiles has some common characteristics that have been described: a central diamond, sitting on point, with pairs of curved or hooked lines projecting from the top and bottom points (Figure 1-2). The diamond represents the body of the pregnant woman and the lines her arms and legs. In some versions, a small diamond sits inside the larger one or the motif is expanded with more hooked or curved lines.

External Link

Variations of Kilim symbols have been used as the cover motifs for the journal Birth, an interdisciplinary journal from the United States. You can view the cover here: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1523-536X

1.1.2 Birth in Renaissance Europe (14th to the 17th centuries)

In the time of the Renaissance, in post-plague Europe, the physiology of childbirth had not been well studied, and very little had been written about it. Birthing was women’s work, it was private, and it was dangerous given the high rates of maternal and infant mortality. Birth, although risky, was celebrated and elaborate preparations were begun months before the baby was due. The very real fears around childbirth resulted in an abundance of items that might provide protection and/or mediation around the process of reproduction. Talismans, birth trays (Figure 1-3), and paintings were often displayed in the home in the hope of ensuring good birthing outcomes for mother and baby. (8)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bartolomeo_Di_Fruosino_-_Desco_da_parto_(verso)_-_WGA01342.jpg

Women were encouraged to look at beautiful images, in particular pictures of the pregnant Madonna (Figure 1-4), the Birth of the Virgin, or the Birth of Saint John the Baptist (Figure 1-5) so they could imagine themselves having a successful birth and healthy baby like the subjects of the paintings. (9) The paintings and birth trays depicted the period immediately after birth at home; a very congenial atmosphere with the woman surrounded by midwives and friends. There are often as many as ten women in the depictions of birth. The artists depicted their subjects in narrative form so the paintings reveal the activities that might have taken place over a period of days. The women are all fully clothed in the dress style of the day and there is no indication of the messiness of birth. A common visual element in the paintings is a female helper carrying food and drink into the room on a wooden tray after the birth.

Did You Know?

Demographers suggest that between 40-50% of people in Europe died in recurring episodes of plague (Black Death) between the 14th and 17th C. In the late 1330s, Florence Italy had a population of 120,000 but by 1427 it had dropped to 37,000 as a result of deaths from the plague.

Reflect

What is my first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in my practice? (5)

Reflect

How do these Renaissance portrayals of birth compare to the birth room in hospital today?

Hand painted birth trays (Figure 1-3) were a common gift to a newly married couple, and were meant to be passed on through generations. On one side of the tray there was often a birth scene and on the other a painting of a baby boy. As with paintings of successful births, it was believed that if the woman was surrounded by, and focused on, images of baby boys, she would produce a male child and a woman’s value was often measured by her ability to produce a boy child.

Although death was common during the 14th-17th century, and many funerary monuments built, there were few tombs honoring women and specifically women who died in childbirth. In fact there is only one ‘contemporary Western representation of death in childbed, whether in obstetrical texts, sacred or secular manuscripts, or monumental art’ (8, p.30) and that is the carved relief of the death of Francesca Tornabouni, surrounded by her midwife and attendants. It was completed by Andrea Verrocchio in 1477, and is currently located in the Bargello Museum in Florence. Francesca’s husband, Giovanni, funded this unique monument as a display of his devotion and grief. Note the anxious facial expressions and arm and body movements of the attendants (Figure 1-6).

The Italian artist Francesco Furini (mid 17th century) painted a childbirth death scene from the Hebrew Bible story of Jacob and Rachel, titled The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel (Figure 1-7). This painting is similar to the Tornabuoni relief in that Rachel is surrounded by her midwife attendants, her body is slumped over like that of Francesca Tornabuoni and the attendants have anxious facial expressions and tense body positions. Visual representations of death in childbirth are rare today but childbirth deaths are more commonly depicted in literature.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_birth_of_Benjamin_and_the_death_of_Rachel._Oil_painting_Wellcome_V0017370.jpg

Reflect

What is my first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in my practice? (5)

Did You Know?

In Renaissance Europe, so little was known about the physiology of birth, its complications or how to treat them that wealthy women would often compose a will when they found out they were pregnant. Families would also take out an insurance policy against a bad outcome.

1.1.3 Late 19th Century, early 20th Century Women Artists and Birth

Art by women began to be taken seriously by art historians and society in the late 19th century. Before that time, it was difficult for women to obtain adequate training and gain professional recognition and status comparable to men. (20) Consequently, many of the earlier representations of the birth room and its many female attendants were made by male artists based on family conversations about the activities that went on. Moving forward to the late 19th and early 20th Century, women were becoming more recognized as competent and talented artists Pregnancy, however, was remarkably underrepresented in the many topics represented in the visual arts until the work of Paula Modersohn-Becker, Frida Kahlo and Alice Neel became respected and commonplace. The art history literature is replete with analyses and critiques of their work. In these works, we feel an intimacy; we are face to face with the subjects, who in fact are the artists in some of these works.

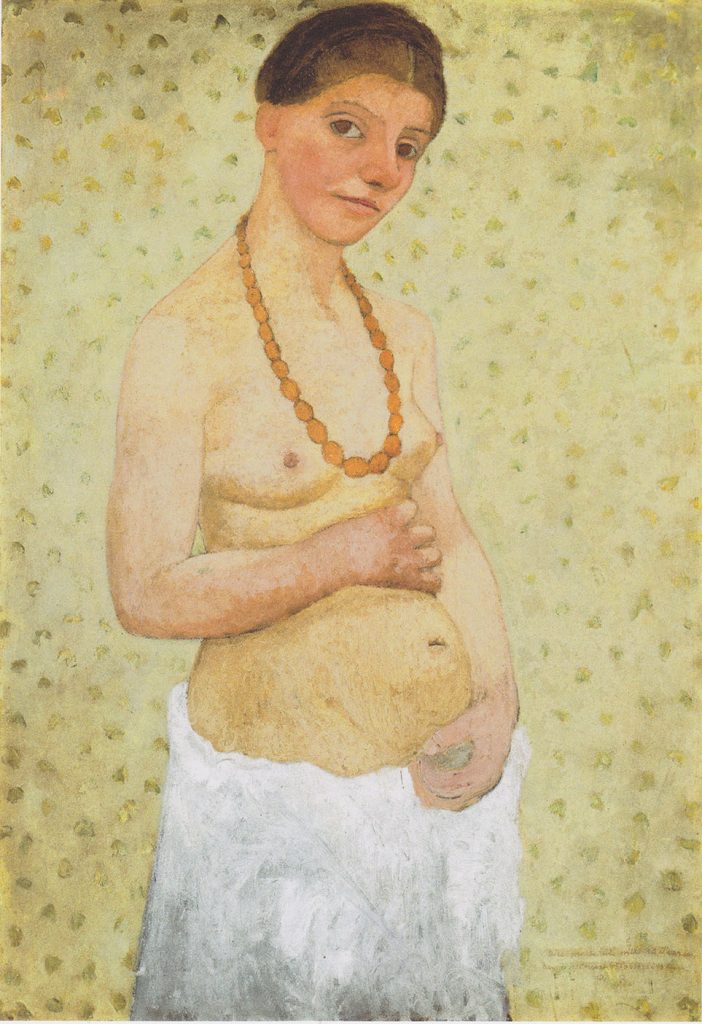

1.1.3.1 Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907)

Paula Modersohn-Becker was born and raised in Germany but moved to France to study painting at the age of twenty-four. She is considered to be the first female painter to paint female nude self-portraits. She compares her own naked body to ‘her soul laid bare’ (11, p.14) in a letter to her husband Otto in 1903. Her nakedness then ‘becomes a metaphor for honesty or openness’ (11, p.14) One of her most well-known self-portraits is a portrait of herself as a pregnant woman, although she had yet to become pregnant (Figure 1-8). This painting is one of the first examples of self-representation; a painting about pregnancy by a woman who is imagining how she would look if pregnant.

The painting, then, is a metaphor for how she felt about herself as a young artist: fecund, ripe, able for the first time in her life to create and paint freely in the manner that she wished. What she is about to give birth to is not a child but her mature, independent, artistic self. Traditionally, nude portraits of women had been painted for the delectation of the male gaze, but here Paula creates a new construct: a woman who is able to nurture herself outside the trappings of marriage, who does not need a man to be fulfilled. (12)

Modersohn-Becker became pregnant at the age of 30, one year after completing, Self-Portrait on Her Sixth Wedding Anniversary. Eighteen days after giving birth to her daughter, Modersohn-Becker died of an embolism (Figure 1-9).

Reflect

How do the events of Modersohn-Becker’s life and death impact your response to her painting?

What is your first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in your practice? (5)

Did You Know?

Following the birth of her daughter, Modersohn-Becker experienced pain in her legs. To treat the pain, her doctor advised her to stay in bed. After more than two weeks immobilized in bed, the doctor advised her to begin walking again. Shortly after taking her first few steps, still experiencing leg pain, she died of an embolism. (12,13)

Did You Know?

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a long poem about his friendship with Modersohn-Becker and his inability to come to terms with her death. You can read Rilke’s ‘Requiem for a Friend’ in Requiem and other Poems (1949).

1.1.3.2 Alice Neel (1900-1984)

Alice Neel was an American painter known for defying the conventions and politics of the day. Although Modersohn-Becker painted soft and beautiful pregnant nudes in the early 1990’s it wasn’t until Neel, in the 1960’s that pregnancy was again in the lexicon of artists. In 1964, after several family and friends became pregnant Neel began painting her sharp, realistic, non-romantic pregnant nudes. She painted seven pregnant nudes between 1964 and 1978 and approached these paintings and all her portraiture with a ‘knowing and unflinching eye.’ (15) Her subjects were women she knew, whose stories were familiar to her. They are painted looking directly at the viewer – which was in contrast to many of the female nudes in European and Asian art who look away from the viewer and the viewer who perhaps has an erotic interest. She wanted to paint in defiance of the male gaze. Nonetheless, her work on pregnancy was not considered an appropriate subject by some feminists because ‘it threatened to provide evidence for the charge – certain to send women back to their suburban prisons – that ‘anatomy is destiny.’’(15,16)

Neel, who was a single mother and whose own history with motherhood is complicated, came to painting her pregnant nudes when she was past menopause, bringing a distance and perspective to the work. Her 1978 painting of Margaret Evans, the wife of a friend of Neel’s, who is carrying twins reflects Neel’s view of pregnancy as a fact of life with its joy and its wretchedness, a condition where women are grounded and not for sale. (17)

External Link

The works of Alice Neel can be viewed on her website: http://www.aliceneel.com/gallery

1.1.3.3 Frida Kahlo, (1907 – 1954)

Kahlo was a Mexican artist whose life was dominated by disability, illness and pain, all of which are represented in her artistic work. She was married to fellow painter Diego Rivera, a love that brought both ecstasy and pain to her life. Kahlo very much wanted to have children and became pregnant several times but the pregnancies each ended in miscarriage. In this context, she painted her experience of a miscarriage while in the United States. Miscarriage was not publicly talked about in the 1930s; it was a source of shame, so her courage in painting this topic reflected her need to speak the unspeakable in the way she knew how. (18)

External Link

Kahlo’s painting Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) can be viewed online here:

https://www.wikiart.org/en/frida-kahlo/henry-ford-hospital-the-flying-bed-1932 or http://www.fridakahlo.org/henry-ford-hospital.jsp

Reflect

What is my first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in my practice? (5)

1.1.4 21st century representations

Today, we are inundated with vivid portrayals of pregnancy and birth. Not only through traditional representations in art, fiction, and poetry but also through explicit images in reality television and online. Today’s media allows pregnancy and birth to be presented with more complexity and enables a wider range of experiences to be represented than could be in the past. Technology lets us participate in, reimagine and, even reuse representations of normal birth, complicated birth, pregnancy and birth with a disability, LGBTQ2 experiences, pregnancy loss, science fiction and avatar births.

In less than 50 years, the portrayals of pregnancy and birth have changed from artist’s representations in text, sculpture and painting to include actual, vivid images we see on television, internet blogs and websites. Anyone with an internet connection can watch a video of labour and birth from beginning to end and view births in hospital, at home, a birth centre, in water, or in standing, squatting, or sitting positions. Social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook all facilitate text, photos and short videos of childbirth. From a distance, even as a stranger to those that post, we can get a glimpse into the meanings of birth for those individuals who post photos and videos.

Luce et al. (19), after reviewing several television episodes showing births, concluded that because of the appeal of ‘emergency’ births with complications, women may enter their own birth experience with fears generated by what they have witnessed. Those fears, she postulates, promote the medicalization of birth.

This fear of childbirth has grown as a topic of research over the past five years. Does access to copious sources of information increase or decrease women’s fears? A Google search of personal stories of birth turns up tens of millions of possible results. How do childbearing clients sort through that information to find, not just accurate information, but stories from others ‘like them’? If one is poor, culturally conservative, religious, what is the impact? Stoll and Hall (20) in their study of over 4,000 students at the University of British Columbia found that ‘young women whose attitudes toward pregnancy and birth were shaped by the media were 1.5 times more likely to report childbirth fear.’ (20) European renaissance women feared childbirth because of what they did not know; today we may fear childbirth because of all we do know.

1.3 Viewing other ways of being

The shifting landscape of representations of childbirth is opening up new ways of seeing and thinking about birth. Only in recent years have we seen representations of bodies and relationships that do not fit the traditional ideal. Disability, and LGBTQ2 experiences are beginning to be depicted.

1.3.1 Disability experience

Individuals with a disability have been marginalized in our society and as such, they are rarely the subjects of art. To some in society, those with disabilities are not meant to be sexual, let alone be pregnant or a parent. (21) Marc Quinn was one of the first to challenge that view through large-scale sculpture. (22) Quinn has made several sculptures of Alison Lapper, while she was pregnant. Lapper is an English artist who was born with phocomelia. Quinn was drawn to Lapper as representing someone who overcame her circumstances. When she became pregnant she was urged to have an abortion so her child would not become a burden to society. She persisted, breastfeed her baby boy, took him to school on her wheelchair, fought for disability rights, and currently earns a living as an artist for the Mouth and Foot Painting Artists. She received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Brighton in 2014.

Quinn’s marble sculpture of Lapper was part of a rotating contemporary sculpture display in Trafalgar Square, London, UK (Figure 1-10), and it publicly celebrated the beauty of a different body. Met with both criticism and praise, the sculpture asks the viewer to question the narrow bounds of accepted social norms.

Did You Know?

A large-scale inflatable reproduction of Alison Lapper Pregnant featured as a centrepiece of the London 2012 Paralympic Games opening ceremony.

Reflect

What is my first response to the work?

When and where was the work made?

Where would the work originally have been seen/heard?

What purpose did/does the work serve?

Is there a title to the work?

What is the subject matter?

Are there gender/power considerations with respect to the subject and maker of the work?

How has my response to the work changed over time?

How could I use this piece of work in my practice? (5)

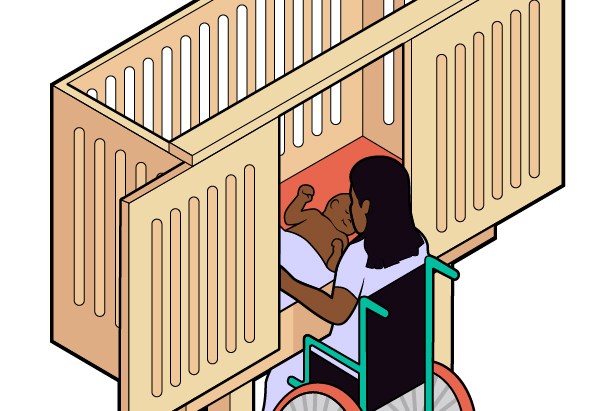

For clients living with a disability, one of the most difficult aspects of learning how to be a parent, or cope with labour, is that there are very few images of parents with disabilities and very few opportunities to meet other parents who have similar needs. (23) There is no lack of images illustrating devices such as baby monitors, high chairs, and strollers for the parent who is able bodied. However, for parents with a disability it is very difficult to find suggestions for assistance, let alone teaching materials that might address their experience. (Figure 1-11).

1.3.2 LGBTQ2 experiences

Only recently has the health literature begun to address the pregnancy and childbearing needs of individuals who identify or present as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or double spirited. Midwifery and doula websites in Canada and elsewhere provide guidelines for sensitive care. Many of the guidelines are based on the philosophy outlined by Canadian Association of Midwives position statement on Gender Inclusivity and Human Rights. (24)

The experience of transgender pregnancy in particular has been described in newspapers and academic text. The photographic images and written text of Thomas Beatie (Figure 1-12) and Yuval Topper’s pregnancies are examples of representations available to us as we imagine the meaning of pregnancy to these men, their families and to society in the future. The opening of the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art, Chicago and the publication of graphic novels such as Pregnant Butch are examples of changes that provide tangible support for the accomplishments and possibilities for transgendered parents.

1.3.3 Representations

We now live in a time when representations of the body in general and the pregnant body in particular are no longer so constrained by social convention. That is not to say that many representations don’t raise questions of ethics or cultural appropriateness. How to interpret the explosion of representations is a challenge for all women and caregivers. Interpretation is influenced by the society we live in. The meaning of pregnancy and of birth is shaped by the society each client lives in resulting in great differences in meaning between rural Nunavut in Canada, urban New York City, or the less developed country of Sierra Leone. Societies are shaped by how women are viewed, how sexuality is viewed and the role of religion in the society and the life of the individual, and each of these will impact on the meaning of birth to a client.

Birth is important. As women have more agency over the expression of representations of this life-changing event, they will be able to experience a meaning that fills them with feelings of strength and comfort. Sharon Olds (25) poem, The Language of the Brag, expresses the joy she feels in using her body in childbirth while utilizing male imagery to describe her strength and feeling of victory.

External Link

Read Sharon Old’s poem The Language of the Brag here: http://www.poetrymagazines.org.uk/magazine/record.asp?id=2160

1.4 Conclusion

As members of a practice profession, midwifery students have an obligation to learn as much as possible about what affects clients, and themselves. As you develop your professional competencies, you have an obligation to interrogate your philosophy, knowledge, skills and attitudes on a regular basis.

As midwifery students, you work ‘with women’ at a time in life that can be celebratory or foreboding or both. You are with a client who has one of many possible family configurations, may have one or more sexual orientations, who may have strong ethno-cultural beliefs, and who may live a life of poverty or privilege. Carry with you the perspectives of each of these varied contexts and enjoy the challenge of understanding those you work with as you and they discover the many meanings of childbirth.

References

- WHO. Celebrate International Day of the Midwife [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Sep 7]. p. 1. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/news_events/events/2015/international-day-midwife/en/

- Sandburg C. Being Born is Important. In: Breathing Tokens. Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt; 1978. p. 192.

- Bolt B. Art beyond representation: The performative power of the image. London: I.B. Tauris and Co. Ltd; 2004. 256 p.

- Burton N, editor. Natal signs: Cultural representations of pregnancy, birth and parenting. Bradford: Demeter Press; 2015. 378 p.

- Smithsonian Institution. What does it mean to be human?: Art & music [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 May 8]. Available from: http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/behavior/art-music

- Encyclopedia of Art Education. History of Art [Internet]. Visual Arts Encyclopedia. 2017 [cited 2017 May 8]. Available from: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/index.htm

- O’Bannon G. A book review of The Birth Symbol by Max Cameron. Orient Rug Rev. 1983;11(2).

- Musacchio J. The Art and Ritual of Childbirth in Renaissance Italy. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1999. 228 p.

- Currie E. Inside the Renaissance House. London: Victoria & Albert Museum; 2006. 96 p.

- Gaze D, editor. Concise Dictionary of Women Artists. New York: Routledge; 2011. 784 p.

- Perry G. Paula Modersohn-Becker: Her Life and Work. New York: Harper & Row; 1979. 149 p.

- Hubbard S. Modersohn-Becker, Paula: Self-Portrait on her Sixth Wedding Anniversary (1906). The Independent [Internet]. London; 2007 Aug 23; Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/great-works/modersohn-becker-paula-self-portrait-on-her-sixth-wedding-anniversary-1906-744437.html

- Colapinto J. Paula Modersohn-Becker: Modern Painting’s Missing Piece. The New Yorker [Internet]. New York; 2013 Oct; Available from: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/paula-modersohn-becker-modern-paintings-missing-piece#slide_ss_0=8

- Paula Modersohn-Becker: Final Year [Internet]. Wikipedia. 2017 [cited 2017 Mar 1]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paula_Modersohn-Becker#Final_year

- Lewison J, Walker B, Garb T, Storr R. Alice Neel: Painted Truths. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2010. 306 p.

- Allara P. “Mater” of Fact: Alice Neel’s Pregnant Nudes. Am Art. 1994;8(2):6–31.

- Hills P. Alice Neel. New York: Harry N. Abrams; 1995.

- Lomas D, Howell R. Medical imagery in the art of Frida Kahlo. BMJ Br Med J. 1989;299:1584–7.

- Luce A, Cash M, Hundley V, Cheyne H, van Teijlingen E, Angell C. “Is it realistic?” the portrayal of pregnancy and childbirth in the media. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2016;16(1):40. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4770672&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

- Stoll K, Hall W. Vicarious birth experiences and childbirth fear: does it matter how young canadian women learn about birth? J Perinat Educ [Internet]. 2013;22(4):226–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24868135%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4010856

- Tomasi P. Parents with Disabilities: These Moms Live in Fear of Losing Their Kids [Internet]. Huffington Post Canada. 2015 [cited 2017 May 8]. Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/05/10/parents-with-disabilities_n_7251484.html

- Artworks: Alison Lapper [Internet]. Marc Quinn. [cited 2017 May 8]. Available from: http://marcquinn.com/artworks/alison-lapper

- Mitra M, Long-Bellil LM, Iezzoni LI, Smeltzer SC, Smith LD. Pregnancy among women with physical disabilities: Unmet needs and recommendations on navigating pregnancy. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(3):457–63.

- Canadian Association of Midwives. A statement on Gender Inclusivity & Human Rights [Internet]. Montreal; 2015. p. 1. Available from: http://canadianmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CAM-GenderInclusivity-HumanRights-Sept2015.pdf

- Olds S. The Language of the Brag. In: Satan Says. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1980. p. 72.