18 Sustainability: Business and the Environment

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the concept of earth jurisprudence

- Evaluate the claim that sustainability benefits both business and the environment

- Identify and describe initiatives that attempt to regulate pollution or encourage businesses to adopt clean energy sources

Public concern for the natural environment is a relatively new phenomenon, dating from the 1960s and Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring, published in 1962. In 1992, Cormac Cullinan’s Wild Law proposed “earth justice” or “earth jurisprudence,” a concept underlying the law’s ability to protect the environment and effectively regulate businesses that pollute. The preoccupation with business success through investment in corporations, in contrast, is a much older concept, dating back at least to the creation of the British East India Company in 1600, and the widespread emergence of the corporation in Europe in the 1700s. If you were a business owner, would you be willing to spend company resources on environmental issues, even if not required to do so by law? If so, would you be able to justify your actions to shareholders and investment analysts as smart business decisions?

Environmental Justice

If a business activity harms the environment, what rights does the environment have to fight back? Corporations, although a form of business entity, are actually considered persons in the eyes of the law. Formally, corporate personhood, a concept we touched on in the preceding section, is the legal doctrine holding that a corporation, separate and apart from the people who are its owners and managers, has some of the same legal rights and responsibilities enjoyed by natural persons (physical humans), based on an interpretation of the word “person” in the Fourteenth Amendment.

The generally accepted constitutional basis for allowing corporations to assert that they have rights similar to those of a natural person is that they are organizations of people who should not be deprived of their rights simply because they act collectively. Thus, treating corporations as persons who have legal rights allows them to enter into contracts with other parties and to sue and be sued in a court of law, along with numerous other legal rights. Before and after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), which upheld the First Amendment free-speech rights of corporations, there have been numerous challenges to the concept of corporate personhood; however, none have been successful. Thus, U.S. law considers corporations to be persons with rights protected under key constitutional amendments, regulations, and case law, as well as responsibilities under the law, just as human persons have.

A question that logically springs from judicial interpretations of corporate personhood is whether the environment should enjoy similar legal status. Should the environment be considered the legal equivalent of a person, able to sue a business that pollutes it? Should environmental advocates have been able to file a lawsuit against BP (formerly British Petroleum) on behalf of the entire Gulf of Mexico for harm created by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill (discussed in more detail in the government regulation section of this chapter), which, at five million barrels, was ten times larger than the famous Exxon Valdez spill and remains the largest and most widespread ocean oil spill in the history of the global petroleum industry? Furthermore, the Deepwater Horizon spill affected not only thousands of businesses and people, but also the entirety of the Gulf of Mexico, which will suffer harm for years to come. Should the Gulf of Mexico have legal standing to sue, just like a person?

While U.S. jurisprudence has not yet officially recognized the concept that Earth has legal rights, there are examples of progress. Ecuador is now the first country to officially recognize the concept.

The country rewrote its Constitution in 2008, and it includes a section entitled “Rights for Nature.” It recognizes nature’s right to exist, and people have the legal authority to enforce these rights on behalf of the ecosystem, which can itself be named as a litigant in a lawsuit.

Earth jurisprudence is an interpretation of law and governance based on the belief that society will be sustainable only if we recognize the legal rights of Earth as if it were a person. Advocates of earth jurisprudence assert that there is legal precedent for this position. As pointed out earlier in this chapter, it is not only natural persons who have legal rights, but also corporations, which are artificial entities. Our legal system also recognizes the rights of animals and has for several decades. According to earth jurisprudence advocates, officially recognizing the legal status of the environment is necessary to preserving a healthy planet for future generations, in particular because of the problem of “invisible pollution.”

Businesses that pollute the environment often hide what they are doing in order to avoid getting caught and facing economic, legal, or social consequences. The only witness may be Earth itself, which experiences the harmful impact of their invisible actions. For example, as revealed in a recent report,

companies all over the world have for years been secretly burning toxic materials, such as carbon dioxide, at night. A company that needs to dump a toxic substance usually has three choices: dispose of it properly at a safe facility, recycle and reuse it, or secretly dump it. There is no doubt that dumping is the easiest and cheapest option for most businesses.

As another example, approximately twenty-five million people board cruise ships every year, and as a result, cruise ships dump one billion gallons (3.8 billion liters) of sewage into the oceans annually, usually at night so no one sees or smells it. Friends of the Earth, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) concerned with environmental issues, used data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to calculate this figure.

The sewage dumped into the sea is full of toxins, including heavy metals, pathogens, bacteria, viruses, and pharmaceutical drugs ((Figure)). When invisibly released near coasts, this untreated sewage can kill marine animals, contaminate seafood, and sicken swimmers, and no one registers the damage except the ocean itself. Many believe the environment should have the right not to be secretly polluted in the dead of night, and Earth should have rights at least equal to those of corporations.

Cormac Cullinan, an environmental attorney, author, and leading proponent of earth jurisprudence, often collaborates with other environmental advocates such as Thomas Berry, an eco-theologian, scholar, and author. Cullinan, Berry, and others have written extensively about the important legal tenets of earth jurisprudence; however, it is not a legal doctrine officially adopted by the United States or any of its states to date. The concept of earth justice is tied indirectly to the economic theory of the “tragedy of the commons,” a phrase derived from British economist William Forster Lloyd, who, in the mid-nineteenth century, used a hypothetical example of unregulated grazing on common land to explain the human tendency to act independently, putting self-interest first, without regard for the common good of all users. The theory was later popularized by ecologist and philosopher Garrett Hardin, who tied it directly to environmental issues. In other words, when it comes to natural resources, the tragedy of the commons holds that people generally use as much of a free resource as they want, without regard for the needs of others or for the long-term environmental effects. As a way of combating the tragedy of the commons, Cullinan and others have written about the concept of earth justice,

which includes the following tenets:

“The Earth and all living things that constitute it have fundamental rights, including the right to exist, to have a habitat or a place to be.

Humans must adapt their legal, political, economic, and social systems to be consistent with the fundamental laws or principles that govern how the universe functions.

Human acts, including acts by businesses that infringe on the fundamental rights of other living things violate fundamental principles and are therefore illegitimate and unlawful.”

The concept of earth justice relies heavily on Garrett Hardin’s discussion of the tragedy of the commons in Science in 1968.

This classic analysis of the environmental dilemma describes how, from colonial times, Americans regarded the natural environment as something to be used for their own farming and business ends. Overuse, however, results in the inevitable depletion of resources that negatively affects the environment, so that it eventually loses all value.

Today, supporters of the environment assert that government has both a right and an obligation to ensure that businesses do not overuse any resource, and to mandate adequate environmental protection when doing so. In addition, some form of fee may be collected for using up a natural resource, such as severance taxes imposed on the removal of nonrenewable resources like oil and gas, or deposits required for possible cleanup costs after projects have been abandoned. As part of the growing acceptance of the concept of earth justice, several nonprofit educational organizations and NGOs have become active in both lobbying and environmental litigation. One such organization is the Center for Earth Jurisprudence (housed at the Barry School of Law in Orlando), a nonprofit group that conducts research in this area.

The following video describing the Center for Earth Jurisprudence discusses support for laws that legally protect the sustainability of life and health on Earth, focusing upon the springs and other waters of Florida.

Why Sustainability Is Good for Business

The notion that the environment should be treated as a person is relatively new. But given the prominence of the environmental movement worldwide, no well-managed business today should be conducted without an awareness of the tenuous balance between the health of the environment and corporate profits. It is quite simply good business practice for executives to be aware that their enterprise’s long-term sustainability, and indeed its profitability, depend greatly on their safeguarding the natural environment. Ignoring this interrelationship between business and the environment not only elicits public condemnation and the attention of lawmakers who listen to their constituents, but it also risks destroying the viability of the companies themselves. Virtually all businesses depend on natural resources in one way or another.

Progressive corporate managers recognize the multifaceted nature of sustainability—a long-term approach to business activity, environmental responsibility, and societal impact. Sustainability affects not only the environment but also other stakeholders, including employees, the community, politics, law, science, and philosophy. A successful sustainability program thus requires the commitment of every part of the company. For example, engineers are designing manufacturing and production processes to meet the demands of companies dedicated to sustainability, and the idea of company-wide sustainability is now mainstream. Many of the largest companies in the world see sustainability as an important part of their future survivability.

The Global 100 and Sustainability’s Strategic Worth

Corporate Knights is a Canadian research and publishing company that compiles an annual list called the Global 100, identifying the world’s most sustainable companies.

The 2018 edition of the list, presented at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, shows that an increasing number of major multinational companies take sustainability seriously, including many U.S. businesses. The highest-ranking U.S. company is technology giant Cisco, which ranks seventh on the Global 100 list.

Other U.S. companies in the top twenty-five include Autodesk, Merck, and McCormick & Co. The countries with the best representation on the list are primarily from North America and Western Europe: the United States (18), France (15), the United Kingdom (10), Germany (7), Brazil (5), Finland (5), and Sweden (5).

You may expect that companies dedicated to sustainability would be less profitable in the long run as they face additional costs. In fact, data from the Global 100’s return on investment shows this is not the case. Let’s examine the evidence. If an investor had put $250 in Global 100 companies in 2005, it would have been worth $580 in 2015, compared to $520 for the same amount invested in a typical index fund. The Global 100’s cumulative return on high-sustainability firms is about 25 percent higher than a traditional investment.

Cisco Systems, number seven on the global list, is a good example of how green procurement and sustainable sourcing have become a regular part of the supply chain. At Cisco, according to a top-level supply chain executive, “we take seriously the responsibility of delivering products in an ethical and environmentally responsible manner.”

Cisco relies on its Supplier Code of Conduct to set standards for suppliers so they follow fair labor practices, ensure safe working conditions, and reduce their carbon footprint, the amount of carbon dioxide and other carbon compounds released by the consumption of fossil fuels, which can be measured quantitatively (see the link below). Cisco is in the process of embedding sustainability into supply chain management at all levels.

Do you know what your carbon footprint is? This personal footprint calculator allows you to find out where you stand.

Another company dedicated to sustainability is Siemens, which was ranked number nine on the 2018 list. Siemens is a multinational industrial conglomerate headquartered in Germany, whose businesses range from power plants to electrical systems and equipment in the medical field and high-tech electronics. Siemens was rated the most energy-efficient firm in its sector, because it produced more dollars in revenue per kilowatt used than any other industrial corporation. This is a standard technique to judge efficiency and demonstrates that Siemens has a low carbon footprint for a company in the industries in which it operates. The commitment of Siemens to sustainability is further demonstrated by its decision to manufacture and sell more environmentally friendly infrastructure products such as green heating and air conditioning systems.

Cisco and Siemens show that businesses across the globe are starting to understand that for a supply chain to be sustainable, companies and their vendors must be partners in a clean and safe environment. Do businesses simply pay lip service to environmental issues while using all available natural resources to make as much money as they can in the present, or are they really committed to sustainability? There is abundant evidence that sustainability has become a policy adopted by businesses for financial reasons, not simply public relations.

McKinsey & Company is one of the world’s largest management consulting firms and a leader in the use of data analytics, both qualitative and quantitative, to evaluate management decisions. McKinsey conducts periodic surveys of companies around the world on matters of importance to corporate leaders. In the 2010 survey, 76 percent of executives agreed that sustainability provides shareholders long-term value, and in the 2014 survey, entitled “Sustainability’s Strategic Worth,” the data indicated that many companies consider cost savings to be the number-one reason for adopting such policies. Cost cutting, improved operations, and efficiency were indicated as the primary reasons for adopting sustainability policies by over one-third of all companies (36%).

Other major studies have demonstrated similar results. Grant Thornton is a leading global accounting and consulting firm. Its 2014 report on CSR showed that the top reason companies cite for moving towards more environmentally responsible business practices is financial savings. Grant Thornton conducted more than 2,500 interviews with clients and business executives in approximately thirty-five countries to discover why companies are making a commitment to sustainable practices. The study found that cost management was the key reason for sustainability (67%).

A specific example is Dell Computers, headquartered outside Austin, Texas, and with operations all over the world. The “Dell Legacy of Good Plan” has set a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all facilities and operations by 50 percent by the year 2020, along with several other environmental goals. As part of this overall plan, Dell created the Connected Workplace, a flex-work program allowing alternative arrangements such as variable work hours to avoid rush hour, full- or part-time work at home flexibility, and job sharing. This sustainability initiative helps the company avoid about seven thousand metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, and, directly related to the financial benefit of sustainability, it saves the company approximately $12 million per year.

However, adopting sustainability policies may require a long-term outlook. A recent article in the Harvard Business Review discussed the issue of sustainability and how it can create real cost savings ((Figure)). “It’s hard for companies to recognize that sustainable production can be less expensive. That’s in part because they have to fundamentally change the way they think about lowering costs, taking a leap of faith . . . that initial investments made in more-costly materials and methods will lead to greater savings down the road. It may also require a willingness to buck conventional financial wisdom by focusing not on reducing the cost of each part but on increasing the efficiency of the system as a whole.”

Sustainability Standards

The International Organization for Standardization, or ISO, is an independent NGO and the world’s largest developer of voluntary international business standards. More than twenty thousand ISO standards now cover matters such as sustainability, manufactured products, technology, food, agriculture, and even healthcare. The adoption and use of these standards by companies is voluntary, but they are widely accepted, and following ISO certification guidelines results in the creation of products and services that are clean, safe, reliable, and made by workers who enjoy some degree of protection from workplace hazards.

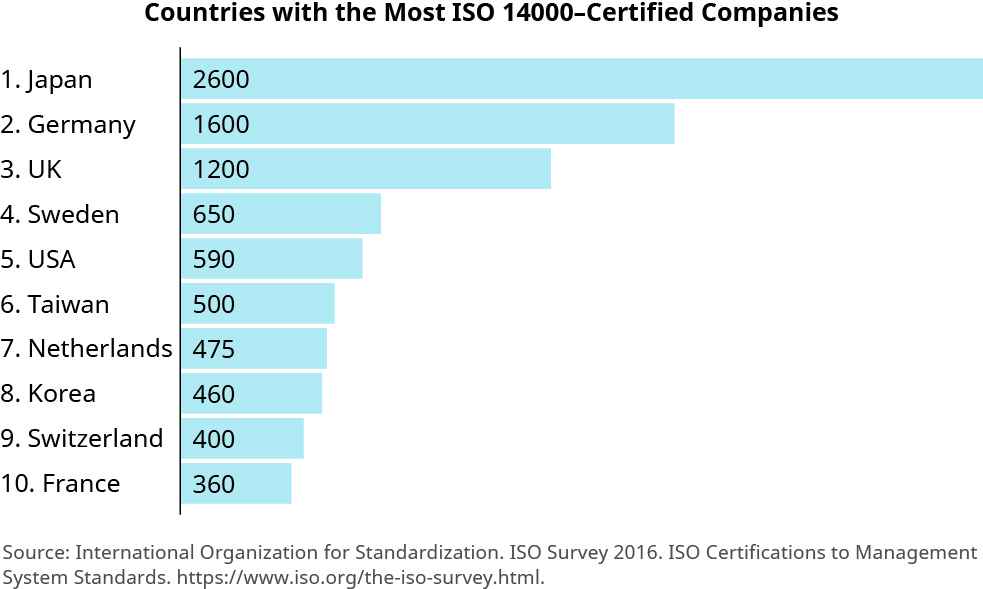

In the environmental area, the ISO 14000 series of standards promotes effective environmental management systems in business organizations by providing cost-effective tools that make use of best practices for environmental management. These standards were developed in the 1990s and updated in 2015; they cover everything from the eco-design (ISO 14006) of factories and buildings to environmental labels (ISO 14020) to limits on the release of greenhouse gasses (ISO 14064). While their adoption is still voluntary, a growing number of countries allow only ISO 14000-certified companies to bid on public government contracts, and the same is true of some private-sector companies ((Figure)).

Another type of sustainability standard with which businesses may elect to comply is LEED certification. LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, and it is a rating system devised by the U.S. Green Building Council to evaluate a structure’s environmental performance. The most famous example is the Empire State Building in New York City, which was awarded LEED Gold status (for existing buildings). The LEED certification was the result of a multimillion-dollar rebuilding program to bring the building up to date, and the building is the tallest in the United States to receive it. There are dozens of other examples of large commercial buildings, such as the Wells Fargo Tower in Los Angeles, as well as thousands of smaller buildings and residential homes. LEED certification is the driver behind the ongoing market transformation towards sustainable design in all types of structures, including buildings, houses, and factories.

The High Cost of Inaction

According to estimates from the EPA, by the year 2050, Earth’s population will be about ten billion people. Dramatic population growth has had a very significant and often negative human impact on the planet. Not only are there more people to feed, house, and care for, but new technologies allow businesses to harness natural resources in unprecedented amounts. NGOs and government agencies alike have taken notice. For years, the Department of State and the Department of Defense have considered climate change to be a potential threat to the long-term security of the United States. If unmanaged, climate change could pose a risk to both U.S. security and Department of Defense facilities and operations.

Other respected organizations are also alerting the public to the risks of ignoring climate change.

The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) has released a detailed report identifying approximately twenty serious risks that will be faced if the problem is not addressed in a substantial way. These risks include rising seas and increased coastal flooding, more intense and frequent heat waves, more destructive hurricanes, wildfires that last longer and produce more damage, and heavier precipitation in some areas and more severe droughts in other areas. In addition to extreme weather events, there would likely be widespread forest death in the Rocky Mountains and other mountain ranges, the destruction of coral reefs, and shifts in the ranges of plants and animals. Both military bases and national landmarks would be at risk, as would the electrical grid and food supply. The UCS, with a membership consisting of the world’s most respected scientists, bases its projections on scientific research studies that have produced empirical evidence of climate change. Its official position is that “global warming is already having significant and very costly effects on communities, public health, and our environment.”

Environmental protection and climate change issues receive varying degrees of support at the national level, depending on the commitment different presidents make to them. During periods in which the administration in Washington demonstrates a lower priority for climate change issues, such as the Trump administration’s announced intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord, private companies may take the lead on actions to reduce global warming emissions.

For example, Microsoft founder Bill Gates recently announced the creation of a private initiative to invest $20 billion on climate-related research and development over the next five years. This is an example of government-funded early experimental research that a business may be able to turn into a commercially viable solution. If government steps back, private-sector companies concerned about long-term sustainability may have to take a leadership role.

Ultimately, it requires the cooperation of public and private efforts to address climate change; otherwise, the impacts will continue to intensify, growing more costly and more damaging.”

This video produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in conjunction with the State Department and an Oregon state agency shows the magnitude of ocean pollution. As of 2017, only two states (California and Hawaii) have banned plastic bags, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Sustainability often requires the public and private sectors to cooperate. Inaction contributes to disasters like the 2017 devastation of Houston by Hurricane Harvey and of Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria. There is often tension between developers who want to build and cities that try to legislate for more green space. Green space not only offers a place for recreation and enjoyment of nature, but also provides essential natural drainage for rain and flood waters, reducing the likelihood that developed areas will end up underwater in a storm.

A symbiotic relationship exists between development and flooding in urban areas such as Houston, Texas. Imagine you are a member of the urban planning commission for the city council of Houston, which recently suffered traumatic flood damage from several major storms, including Hurricanes Harvey and Ike, and Tropical Storm Allison, all of which occurred since 2001 and caused a total of approximately $75 billion in damages.

The floods also caused dozens of deaths and changed the lives of millions who lived through them. Future storms may increase in severity, because climate change is warming ocean waters.

The mayor and the city council have asked the planning commission to propose specific solutions to the flooding problem. This solution must not rely exclusively on taxpayer funds and government programs, but rather must include actions by the private sector as well.

One of the most direct solutions is a seemingly simple tradeoff: The greater Houston area must reduce the percentage of land covered by concrete while increasing the percentage of land dedicated to green space, which acts like a sponge to absorb flood waters before they can do severe damage. The planning commission thinks the best way to accomplish this is to issue a municipal ordinance requiring corporate developers and builders to set aside as green space an amount of land at least equal to what will be covered by concrete, (neighborhoods, office buildings, parking lots, shopping centers). However, this will increase the cost of development, because it means more land will be required for each type of project, and as a result, developers will have higher land costs.

Critical Thinking

- As a member of the urban planning commission, you will have to convince the stakeholders that a proposal to require more green space is a workable solution. You must get everyone, including developers, investors, neighborhood homeowner associations, politicians, media, and local citizens, on board with the idea that the benefit of sustainable development is worth the price. What will you do?

- Is this a matter that should be regulated by the local, state, or federal government? Why?

- Who pays for flood damage after a hurricane? Are your answers to this question and the preceding one consistent?

U.S. government agencies, such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, have identified many challenges in which sustainability can make a positive contribution. These include climate change, decreasing supplies of clean water, loss of ecological systems, degradation of the oceans, air pollution, an increase in the use and disposal of toxic substances, and the plight of endangered species.

Progress toward solving these challenges depends in part on deciding who should help pay for the protection of global environmental resources; this is an issue of both environmental and distributive justice.

One way to address the issue of shared responsibility between corporations and society is the implementation of a “cap and trade” system. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, cap and trade is a viable approach to addressing climate change by curbing emissions that pollute the air: The “cap” is a limit on greenhouse gas emissions—if companies exceed their cap, they must pay penalties—whereas the “trade” allows companies to use the free market to buy and sell pollution allowances that permit them to emit a certain amount of pollution.

At present, there are more questions than answers, including how much of the responsibility lies with governments, how this responsibility can be allocated between developed and developing nations, how much of the cost should the private sector bear, and how should these divisions of cost and responsibility be enforced. Private companies must bear part of the cost, and the business sector recognizes they have some responsibility, but many disagree on whether that should be in the form of after-the-fact fines, or before-the-fact fees and deposits paid to the government. Regulations may very well have to be international in scope, or companies from one country may abuse the environment in another.

Should a multinational company take advantage of another country’s lack of regulation or enforcement if it saves money to do so?

A New York Times news correspondent reporting from Nigeria found a collection of steel drums stacked behind a village’s family living compound. In this mid-1990s case, ten thousand barrels of toxic waste had been dumped where children live, eat, and drink.

As safety and environmental hazard regulations in the United States and Europe have driven toxic waste disposal costs up to $3,000 per ton, toxic waste brokers are looking for the poorest nations with the weakest laws, often in West Africa, where the costs might be closer to $3 per ton. The companies in this incident were looking for cheap waste-dumping sites, and Nigeria agreed to take the toxic chemical waste without notifying local residents. Local people wearing shorts, t-shirts, and sandals unloaded barrels of polychlorinated biphenyls, placing them next to a residential area. Nigeria has often been near the top of the United Nations’ list of most corrupt nations, with government leaders cutting deals to line their own pockets while exposing their citizens to environmental hazards.

A more recent example occurred in Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) in 2006, when residents discovered that hundreds of tons of “slops” (chemicals) from a foreign-owned ship had been dumped near Abidjan, the country’s commercial capital. The ship was owned by a multinational energy company named Trafigura. According to a report from Amnesty International, more than 100,000 residents were sickened, leading to fifteen deaths. Trafigura had illegally dumped the toxic waste in Côte d’Ivoire after searching for a disposal site in several other countries.

Critical Thinking

- Should a U.S. or European company take advantage of a country’s weak approach to business and political ethics?

- Would your answer change if your decision saved your company $1 million?

Inaction on issues of sustainability can lead to long-term environmental consequences that may not be reversible (the death of ocean coral, the melting of polar ice caps, deforestation). Another hurdle is that it is sometimes difficult to convince companies and their investors that quarterly or annual profits are short-term and transitory, whereas environmental sustainability is long-term and permanent.

Environmental Economics and Policy

Some politicians and business leaders in the United States believe that the U.S. system of capitalism and free enterprise is the main reason for the nation’s prosperity over the past two hundred years and the key to its future success. Free enterprise was very effective in facilitating the economic development of the United States, and many people benefited from it. But it is equally true that this could not have happened without the country’s wealth of natural resources like oil, gas, timber, water, and many others. When we consider the environment and the role of sustainability, the question is not whether our system works well with an abundance of natural resources. Rather, we should ask how well it would work in a nation, indeed in a world, in which such resources were severely limited.

Does business, as the prime user of these resources, owe a debt to society? The Harvard Business Review recently conducted a debate on this topic on its opinion/editorial pages. Business owes the world everything and nothing, according to Andrew Winston, author and consultant on environmental and social challenges. “It’s an important question,” he wrote, “but one that implies business should do the socially responsible thing out of a sense of duty. This idea is a distraction. Sustainability in business is not about philanthropy, but about profitability, innovation, and growth. It’s just plain good business.”

On the other hand, Bart Victor, professor at Vanderbilt University’s Owen Graduate School of Management, wrote, “Business is far more powerful and deeply influential than any competing ideological force, political force or environmental force . . . business now has to see itself and its responsibilities and obligations in a new way.”

Using deontological or duty-based reasoning, we might conclude that business does owe a debt to the environment. A basic moral imperative in a normative system of ethics is that someone who uses something must pay for it. In contrast, a more utilitarian philosophy might hold that corporations create jobs, make money for shareholders, pay taxes, and produce things that people want; thus, they have done their part and do not owe any other debt to the environment or society at large. However, utilitarianism is often regarded as a “here and now” philosophy, whereas deontology offers a longer-term approach, taking future generations into account and thus aligning more with sustainability.

Should businesses have to pay more in fees or taxes than ordinary citizens for public resources or infrastructure they use to make a profit? Consider the example of fracking: West Texas has seen a recent boom in oil and gas drilling due to this relatively new process. Fracking is short for hydraulic fracturing, which creates cracks in rocks beneath Earth’s surface to loosen oil and gas trapped there, thus allowing it to flow more easily to the surface. Fracking has led to a greatly expanded effort to drill horizontally for oil and gas in the United States, especially in formations previously thought to be unprofitable, because there was no feasible way to get the fossil fuels to the surface. However, it comes with a significant downside.

Fracking requires very heavy equipment and an enormous amount of sand, chemicals, and water, most of which must be trucked in. Traffic around Texas’s small towns has increased to ten times the normal amount, buckling the roads under the pressure of a never-ending stream of oil company trucks. The towns do not have the budget to repair them, and residents end up driving on dangerous roads full of potholes. The oil company trucks are using a public resource, the local road system, often built with a combination of state and local taxpayer funds. They are obviously responsible for more of the damage than local residents driving four-door sedans to work. Shouldn’t the businesses have to pay a special levy to repair the roads? Many think it is unfair for small towns to have to burden their taxpayers, most of whom are not receiving any of the profits from oil and gas development, with the cost of road repair. An alternative might be to impose a Pigovian tax, which is a fee assessed against private businesses for engaging in a specific activity (proposed by British economist A. C. Pigou). If set at the proper level, the tax is intended as a deterrent to activities that impose a net cost—what economists call “negative externalities”—on third parties such as local residents.

This issue highlights one of many environmental debates sparked by the fracking process. Fracking also causes the overuse and pollution of fresh water, spills toxic chemicals into the ground water, and increases the potential for earthquakes due to the injection wells drilled for chemical disposal. Ultimately, as is often the case with issues stemming from natural resource extraction, local residents may receive a few short-term benefits from business activity related to drilling, but they end up suffering a disproportionate share of the long-term harm.

One method of dealing with the long-term harm caused by pollution is a carbon tax, that is, a “pay-to-pollute” system that charges a fee or tax to those who discharge carbon into the air. A carbon tax serves to motivate users of fossil fuels, which release harmful carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at no cost, to switch to cleaner energy sources or, failing that, to at least pay for the climate damage they cause, based on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions generated from burning fossil fuels. A proposal to implement a carbon tax system in the United States has been recommended by many organizations, including the conservative Climate Leadership Council (CLC).

Exxon Mobil, Shell, British Petroleum, and Total, along with other oil companies and a number of large corporations in other industries, recently announced their support for the plan to tax carbon emissions put forth by the CLC.

Visit the Carbon Tax Center to learn about the carbon tax as a monetary disincentive.

Would this “pay-to-pollute” method actually work? Will companies agree to repay the debt they owe to the environment? Michael Gerrard, the director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University Law School, said, “If a sufficiently high carbon tax were imposed, it could accomplish a lot more for fighting climate change than liability lawsuits.”

Initial estimates are that if the program were implemented, companies would pay more than $200 billion a year, or $2 trillion in the first decade, an amount deemed sufficient to motivate the expanded use of renewable sources of energy and reduce the use of nonrenewable fossil fuels.

Some environmental organizations, including the Nature Conservancy and the World Resources Institute, are also endorsing the plan, as are some legislators in Washington, DC. “The basic idea is simple,” Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) said. “You levy a price on a thing you don’t want—carbon pollution—and you use the revenue to help with things you do want.”

According to the senator, a U.S. carbon tax or a fee of $45 per metric ton would reduce U.S. carbon emissions by more than 40 percent in the first decade. This is an idea with global support, and it has already been tried. The World Bank has data indicating that forty countries, along with some major cities, have already enacted such programs, including all countries of the EU, as well as New Zealand and Japan.

The car manufacturer Tesla is developing new technologies to allow people to reduce their carbon footprint. In addition to a line of electric cars, the company makes other renewable energy products, such as roofing tiles that act as solar energy panels, and promotes longer-term projects such as the Hyperloop, a high-speed train project jointly designed by Tesla and SpaceX.

Of course, if businesses are to succeed in selling environmentally friendly products, they must have consumers willing to buy them. A homeowner has to be ready to spend 20 percent more than the cost of a traditional roof to install solar roofing tiles that reduce the consumption of electricity generated by fossil fuels ((Figure)).

Another personal decision is whether to buy a $35,000 Tesla Model 3 electric car. While it reduces the driver’s carbon footprint, it requires charging every 250 miles, making long-distance travel a challenge until a national system of charging stations is in place.

Tesla’s founder, Elon Musk, is also the founder of SpaceX, an aerospace manufacturer that produces and launches the only space-capable rockets currently in existence in the United States. Thus, when NASA wants to launch a rocket, it must do so in partnership with SpaceX, a private company. It is often the case that private companies develop important advances in technology, with incentives from government such as tax credits, low-interest loans, or subsidies. This is the reality of capital-intensive, high-tech projects in a free-market economy, in which government spending may be limited for budgetary and political reasons. Not only is SpaceX making the rockets, but it is making them reusable, with long-term sustainability in mind.

Critical Thinking

- Should corporations and individual consumers bear joint responsibility for sustaining the environment? Why or why not?

- What obligation does each of us have to be aware of our own carbon footprint?

- If individual consumers have some obligation to support environmentally friendly technologies, should all consumers bear this responsibility equally? Or just those with the economic means to do so? How should society decide?

Elon Musk, founder of the electric car manufacturer Tesla and other companies, recently spoke at a global conference held at the Panthéon-Sorbonne University in Paris. In this video, Musk explains the effect of carbon dioxide emissions on climate change in clear and simple terms.

Summary

Adopting sustainability as a strategy means protecting the environment. Society has an interest in the long-term survival, indeed the flourishing, of ecological habitats and natural resources, and we ask and expect companies to respect this societal goal in their business activities.

When analyzing what a business owes society in return for the freedom to extract our natural resources, we must balance development and preservation. It may be easy to say from afar that a business should cut back on how much it pollutes the air, but what happens when that means cutting back on fossil fuel use and transitioning to electric vehicles, a choice that affects everyone on a personal level?

Assessment Questions

What is earth jurisprudence?

Earth jurisprudence is an interpretation of law and governance based on the belief that society will be sustainable only if we recognize the legal rights of Earth as if it were a person.

Which of the following best describes the tragedy of the commons?

- People are always willing to sacrifice for the good of society.

- People are likely to use all the natural resources they want without regard to others.

- The common good of the people is a popular corporate goal.

- Tragedies occur when there is too much government regulation.

B

ISOs are sustainability standards for businesses ________.

- promulgated by the state government

- promulgated by the federal government

- promulgated by the World Trade Organization

- none of the above

D

True or false? If environmental harm is discovered, the business entity causing it is frequently held liable by both the government and the victims of the harm in separate proceedings.

True

Which of the following is a potentially effective way to reduce global warming?

- build more coal-burning power plants

- build more diesel-burning cars

- implement a carbon tax

- implement tax-free gasoline

C

Endnotes

Glossary

- cap and trade

- a system that limits greenhouse gas emissions by companies while allowing them to buy and sell pollution allowances

- carbon footprint

- the amount of carbon dioxide and other carbon compounds released by the consumption of fossil fuels

- carbon tax

- a pay-to-pollute system in which those who discharge carbon into the air pay a fee or tax

- corporate personhood

- the legal doctrine holding that a corporation, separate and apart from the people who are its owners and managers, has some of the same legal rights and responsibilities enjoyed by natural persons

- sustainability

- a long-term approach to the interaction between business activity and societal impact on the environment and other stakeholders

- tragedy of the commons

- an economy theory highlighting the human tendency to use as much of a free natural resource as wanted without regard for others’ needs or for long-term environmental effects or issues