23 Business Ethics over Time

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the ways ethical standards change over time

- Identify major shifts in technology and ethical thinking over the last five hundred years

- Explain the impact of government and self-imposed regulation on ethical standards and practices in the United States

Besides culture, the other major influence in the development of business ethics is the passage of time. Ethical standards do not remain fixed; they transform in response to evolving situations. Over time, people change, technology advances, and cultural mores (i.e., acquired culture and manners) shift. What was considered an appropriate or accepted business practice one hundred or even fifty years ago may not carry the same moral weight it once did. However, this does not mean ethics and moral behavior are relative. It simply acknowledges that attitudes change in relationship to historical events and that cultural perspective and the process of acculturation are not stagnant.

Shifts in Cultural and Ethical Standards

We find an example of changing cultural mores in the fashion industry, where drastic evolution can occur even over ten years, let alone a century. The changes can be more than simply stylistic ones. Clothing reflects people’s view of themselves, their world, and their values. A woman in the first half of the twentieth century might be very proud to wear a fox stole with its head and feet intact ((Figure)). Today, many would consider that an ethical faux pas, even as the use of fur remains common in the industry despite active campaigns against it by organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. At the same time, cosmetics manufacturers increasingly pledge not to test their products on animals, reflecting changing awareness of animals’ rights.

Bias is built into the human psyche and expressed through our social structures. For this reason, we should avoid making snap judgments about past eras based on today’s standards. The challenge, of course, is to know which values are situational—that is, although many values and ethics are relative and subjective, others are objectively true, at least to most people. We can hardly argue in favor of slavery, for example, no matter in which culture or historical era it was practiced. Of course, although some values strike us as universal, the ways in which they are interpreted and applied vary over time, so that what was once acceptable no longer is, or the reverse.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, cigarettes were as common as water bottles are today. Nearly everyone smoked, from judges in court to factory workers and pregnant women. Edward Bernays, the Austrian-American founder of the field of public relations, promoted smoking among women in a 1929 campaign in New York City in which he marketed Lucky Strike cigarettes as “torches of freedom” that would lead to equality between men and women. However, by the late 1960s, and in the wake of the release of the landmark Surgeon General’s report on “Smoking and Health” on January 11, 1964, it had become clear that there was a direct link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Subsequent research has added heart and lung diseases, stroke, and diabetes. Smoking has decreased in Western countries but remains well established in the global East and South, where cigarette manufacturers actively promote the products in markets like Brazil, China, Russia, and Singapore, especially among young people.

Critical Thinking

Are such practices ethical? Why or why not?

Explore these statistics on cigarette smoking in young adults from the CDC and these charts on the global state of smoking from the World Bank for information about cigarette use in the United States and globally, including demographic breakdowns of smoking populations.

Thus, we acknowledge that different eras upheld different ethical standards, and that each of these standards has had an impact on our understanding of ethics today. But this realization raises some basic questions. First, what should we discard and what should we keep from the past? Second, on what basis should we make this decision? Third, is history cumulative, progressing onward and upward through time, or does it unfold in different and more complicated ways, sometimes circling back upon itself?

The major historical periods that have shaped business ethics are the age of mercantilism, the Industrial Revolution, the postindustrial era, the Information Age, and the age of economic globalization, to which the rise of the Internet contributed significantly. Each of these periods has had a different impact on ethics and what is considered acceptable business practice. Some economists believe there may even be a postglobalization phase arising from populist movements throughout the world that question the benefits of free trade and call for protective measures, like import barriers and export subsidies, to reassert national sovereignty.

In some ways, these protectionist reactions represent a return to the theories and policies that were popular in the age of mercantilism.

Unlike capitalism, which views wealth creation as the key to economic growth and prosperity, mercantilism relies on the theory that global wealth is static and, therefore, prosperity depends on extracting wealth or accumulating it from others. Under mercantilism, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the exploration of newly opened markets and trade routes coincided with the impulse to colonize, producing an ethical code that valued acculturation by means of trade and often brute force. European powers extracted raw commodities like cotton, silk, diamonds, tea, and tobacco from their colonies in Africa, Asia, and South America and brought them home for production. Few questioned the practice, and the operation of business ethics consisted mainly of protecting owners’ interests.

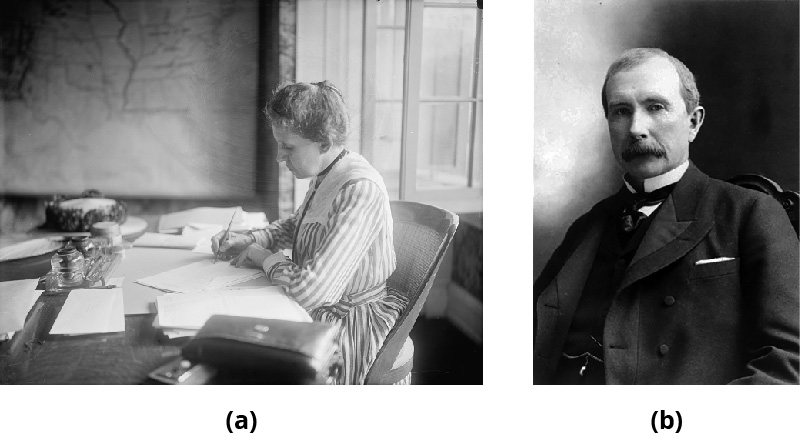

During the Industrial Revolution and the postindustrial era, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, business focused on the pursuit of wealth, the expansion of overseas markets, and the accumulation of capital. The goal was to earn as high a profit as possible for shareholders, with little concern for outside stakeholders. Charles Dickens (1812–1870) famously exposed the conditions of factory work and the poverty of the working class in many of his novels, as did the American writer Upton Sinclair (1878–1968). Although these periods witnessed extraordinary developments in science, medicine, engineering, and technology, the state of business ethics was perhaps best described by critics like Ida Tarbell (1857–1944), who said of industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937) ((Figure)), “Would you ask for scruples in an electric dynamo?”

With the advent of the Information and Internet ages in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a code of professional conduct developed for the purpose of achieving goals through strategic planning.

In the past, ethical or normative rules were imposed from above to lead people toward right behavior, as the company defined it. Now, however, more emphasis is placed on each person at a firm embracing ethical standards and following those dictates to arrive at the appropriate behavior, whether at work or when off the clock.

The creation of human resources departments (increasingly now designated as human capital or human assets departments) is an outgrowth of this philosophy, because it reflects a view that humans have a unique value that ought not be reduced simply to the notion that they are instruments to be manipulated for the purposes of the organization. Millennia earlier, Aristotle referred to “living tools” in a similar but critical way.

Although one characteristic of the information age—access to information on an unprecedented scale—has transformed business and society (and some say made it more egalitarian), we must ask whether it also contributes to human flourishing, and to what extent business should concern itself with this goal.

A Matter of Time

What effect does time have on business ethics, and how is this effect achieved? If we accept that business today has two purposes—profitability and responsibility—we might assume that business ethics is in a much better position now than in the past to affect conduct across industries. However, much of the transformation of business over time has been the result of direct government intervention; one recent example is the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that followed the financial crisis of 2008. Yet, despite such regulation and increased management vigilance in the form of ethics training, compliance reporting, whistleblower programs, and audits, it is tempting to conclude that business ethics is in worse shape than ever. The Information Age and the Internet may even have facilitated unethical behavior by making it easier to move large sums of money around undetected, by enabling the spread of misinformation on a global scale, and by exposing the public to the theft and misuse of vast stores of personal data gathered by companies as diverse as Equifax and Facebook.

However, since the mercantile era, there has been a gradual increase in awareness of the ethical dimension of business. As we saw in the preceding chapter, businesses and the U.S. government have debated and litigated the role of corporate social responsibility throughout the twentieth century, first validating the rule of shareholder primacy in Dodge v. Ford Motor Company (1919) and then moving away from a strict interpretation of it in Shlensky v. Wrigley (1968). In Dodge v. Ford Motor Company (1919), the Michigan Supreme Court famously ruled that Ford had to operate in the interests of its shareholders as opposed to its employees and managers, which meant prioritizing profit and return on investment. This court decision was made even though Henry Ford had said, “My ambition is to employ still more men, to spread the benefits of this industrial system to the greatest possible number, to help them build up their lives and their homes. To do this we are putting the greatest share of our profits back in the business.”

By mid-century and the case of Shlensky v. Wrigley (1968), the courts had given boards of directors and management more latitude in determining how to balance the interests of stakeholders.

This position was confirmed in the more recent case of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), which held that corporate law does not require for-profit corporations to pursue profit at the expense of everything else.

Governmental regulation and legal interpretations have not been the only avenues of change over the past century. The growing influence of consumers has been another driving force in recent attempts by businesses to self-regulate and voluntarily comply with global ethical standards that ensure basic human rights and working conditions. The United Nations (UN) Global Compact is one of these standards. Its mission is to mobilize companies and stakeholders to create a world in which businesses align their strategies and operations with a set of core principles covering human rights, labor, the environment, and anticorruption practices. The Global Compact is a “voluntary initiative based on CEO commitments to implement universal sustainability principles and to undertake partnerships in support of UN goals.”

Of course, as a voluntary initiative, the initiative does not bind corporations and countries to the principles outlined in it.

Read the Ten Principles of the United Nations Global Compact urging corporations to develop a “principled approach to doing business.” The principles cover human rights, labor, the environment, and corruption.

Whenever we look at the ways in which our perception of ethical business practice changes over time, we should note that such change is not necessarily good or bad but rather a function of human nature and of the ways in which our views are influenced by our environment, our culture, and the passage of time. Many of the examples discussed thus far illustrate a gradual increase in social awareness due to the actions of individual leaders and the historical era in which they found themselves. This does not mean that culture is irrelevant, but that human nature exists and ethical inclination is part of that nature. Historical conditions may allow this nature to be expressed more or less fully. We might measure ethical standards according to the degree they allow human compassion to direct business practice or, at least, make it easier for compassion to hold sway. We might then consider ethics not just a nicety but a constitutive part of business, because it is an inherent human trait. This is a perspective Kant and Rawls might have agreed with. Ethical thinking over time should be measured, deliberate, and open to examination.

Summary

As a function of culture, ethics is not static but changes in each new era. Technology is a driving force in ethical shifts, as we can see in tracing changes from the age of mercantilism to the Industrial Revolution to the postindustrial era and the Information Age. Some of the most successful recent efforts to advance ethical practices have come from influences outside industry, including government regulation and consumer pressure.

Assessment Questions

Protecting owners’ interests was a common feature of ________.

- the Industrial Revolution

- the Information Age

- the Dodd-Frank Act

- muckraking

A

True or false? All ethical standards are relative and should be treated as such.

False. Certain core ethics exist throughout cultures and time, although they may manifest in different ways.

True or false? The United Nations Global Compact is a set of standards that is binding worldwide.

False. The UN Global Compact is a voluntary set of standards; it is not legally binding on countries or corporations.

What did the decision in Shlensky v. Wrigley (1968) establish in ethical terms? How does it compare to the decision in Dodge v. Ford Motor Company (1919)?

Shlensky v. Wrigley gave boards of directors and management more latitude in determining how to balance the interests of stakeholders. This was in contrast to Dodge v. Ford Motor Company, which validated the rule of shareholder primacy.

Endnotes

Glossary

- mercantilism

- the economic theory that global wealth is static and prosperity comes from the accumulation of wealth through extraction of resources or trade