7 Accounting and Finance

Learning Objectives

Define what is meant by accounting and bookkeeping.

Identify the steps in the accounting process.

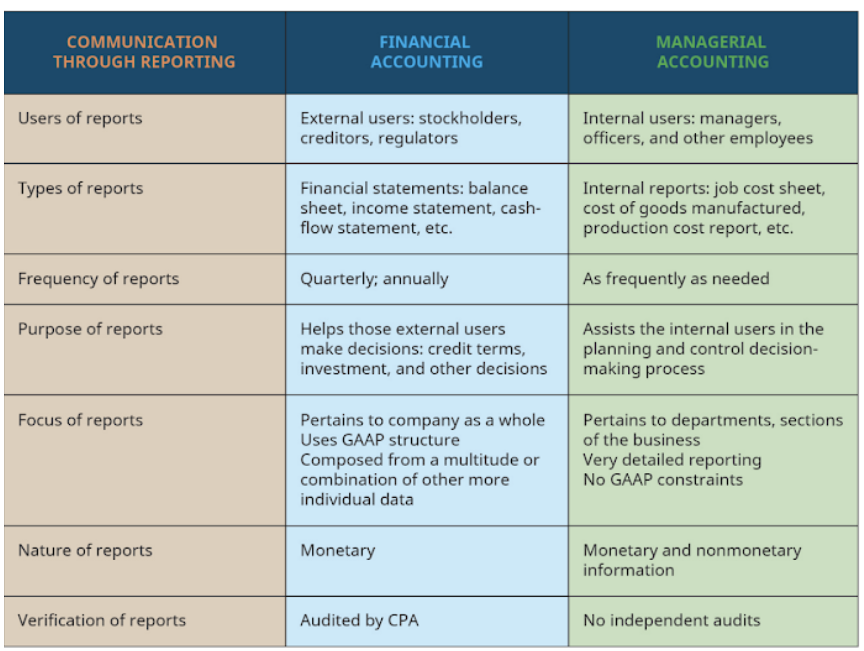

Explain the differences between managerial accounting and financial accounting.

Identify some of the users of accounting information and explain how they use it.

Discuss how accounting information is used by businesses.

Identify the core aspects of finance and financial markets.

Introduction

All of you, at some point of time, would have visited a grocery shop or a medical shop. You might have wondered how the owner maintains the record of all the transactions done during a particular period of time, say a year. You might have also wondered why the owner has to maintain records, how is it beneficial, and whether maintaining records is mandatory? Now imagine the role of a business organization in the wider world. It could provide goods that range from simple safety pins to fighter aircraft. Those who are in the service industry provide various services such as transportation services, hospitality services, developing complex software programs and more. To make sound ands reasoned decisions, a business enterprise needs accounting information. This information is also needed by government agencies, regulatory bodies, analysts, and individuals at various points of time and at different levels. Accounting is one of the oldest, structured management information systems. It has evolved in response to the social and economic needs of society. Accounting, as an information system, is concerned with identification, measurement, and communication of economic information of an organization to its users who may need the information for rational decision making. The accounting system is a means to provide relevant and reliable financial information to all the interested parties.

In this unit, we will understand the meaning of accounting, book-keeping, accountancy, and the steps involved in the accounting process. We will also discuss the various objectives of accounting, the differences between book-keeping, accountancy, and accounting along with how accounting information is used by various stakeholders. We will also focus on the basic terminologies used in accounting.

Example

Apple Inc. is one of the most valuable companies in the world (on February 7th 2022 it was the largest). This statement is based on market value, which in April 2018 was roughly $841 billion and reached more than $2.8 Trillion (that’s quite a lot) in 2022. Although markets can fluctuate, sometimes wildly, if you are reading this chapter for a course in 2022 or even later, it is not unlikely that Apple will have retained its leadership position. Its value as of February 2022 was more than $600 billion greater than that of the next largest company, Microsoft. Apple has briefly ceded the leadership position to other companies, on a couple of occasions, but for the most part, it has been the leader for quite some time.

You may wonder what kind of information is used to make these determinations. How does the market know that Apple should be valued almost $1 Trillion higher than Alphabet in February 2022? Do investors just make their decisions on instinct? Well, some do, but it’s not a formula for sustained success. In most cases, in deciding how much to pay for a company, investors rely on published accounting and financial information released by publicly-traded companies. This chapter will introduce you to the subject of accounting and financial information so you can begin to get an understanding for how the valuation process works.

(Figures obtained from https://companiesmarketcap.com/ February 7, 2022 at 9:21am)

Role of Accounting In Society

Why it Matters

Jennifer has been in the social work profession for over 25 years. After graduating college, she started working at an agency that provided services to homeless women and children. Part of her role was to work directly with the homeless women and children to help them acquire adequate shelter and other necessities. Jennifer currently serves as the director of an organization that provides mentoring services to local youth.

Looking back on her career in the social work field, Jennifer indicates that there are two things that surprised her. The first thing that surprised her was that as a trained social worker she would ultimately become a director of a social work agency and would be required to make financial decisions about programs and how the money is spent. As a college student, she thought social workers would spend their entire careers providing direct support to their clients. The second thing that surprised her was how valuable it is for directors to have an understanding of accounting. She notes, “The best advice I received in college was when my advisor suggested I take an accounting course. As a social work student, I was reluctant to do so because I did not see the relevance. I didn’t realize so much of an administrator’s role involves dealing with financial issues. I’m thankful that I took the advice and studied accounting. For example, I was surprised that I would be expected to routinely present to the board our agency’s financial performance. The board includes several business professionals and leaders from other agencies. Knowing the accounting terms and having a good understanding of the information contained in the financial reports gives me a lot of confidence when answering their questions. In addition, understanding what influences the financial performance of our agency better prepares me to plan for the future.”

Importance of Accounting and Forms of Accounting

Accounting is the process of organizing, analyzing, and communicating financial information that is used for decision-making. Financial information is typically prepared by accountants—those trained in the specific techniques and practices of the profession. This chapter explores some of the topics and techniques related to the accounting profession. While many students will directly apply the knowledge gained to continue their education and become accountants and business professionals, others might pursue different career paths. However, a solid understanding of accounting can for many still serve as a useful resource. In fact, it is hard to think of a profession where a foundation in the principles of accounting would not be beneficial. Therefore, one of the goals of this part of the course is to provide a solid understanding of how financial information is prepared and used in the workplace, regardless of your particular career path.

A traditional adage states that “accounting is the language of business.” While that is true, you can also say that “accounting is the language of life.” At some point, most people will make a decision that relies on accounting information. For example, you may have to decide whether it is better to lease or buy a vehicle. Likewise, a college graduate may have to decide whether it is better to take a higher-paying job in a bigger city (where the cost of living is also higher) or a job in a smaller community where both the pay and cost of living may be lower.

In a professional setting, a theater manager may want to know if the most recent play was profitable. Similarly, the owner of the local plumbing business may want to know whether it is worthwhile to pay an employee to be “on call” for emergencies during off-hours and weekends. Whether personal or professional, accounting information plays a vital role in all of these decisions.

You may have noticed that the decisions in these scenarios would be based on factors that include both financial and non-financial information. For instance, when deciding whether to lease or buy a vehicle, you would consider not only the monthly payments but also such factors as vehicle maintenance and reliability. The college graduate considering two job offers might weigh factors such as working hours, ease of commuting, and options for shopping and entertainment. The theater manager would analyze the proceeds from ticket sales and sponsorships as well as the expenses for production of the play and operating the concessions. In addition, the theater manager should consider how the financial performance of the play might have been influenced by the marketing of the play, the weather during the performances, and other factors such as competing events during the time of the play. All of these factors, both financial and non-financial, are relevant to the financial performance of the play. In addition to the additional cost of having an employee “on call” during evenings and weekends, the owner of the local plumbing business would consider non-financial factors in the decision. For instance, if there are no other plumbing businesses that offer services during evenings and weekends, offering emergency service might give the business a strategic advantage that could increase overall sales by attracting new customers.

This chapter explores the role that accounting plays in society. You will learn about financial accounting, which measures the financial performance of an organization using standard conventions to prepare and distribute financial reports. Financial accounting is used to generate information for stakeholders outside of an organization, such as owners, stockholders, lenders, and governmental entities such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Revenue Canada.

Financial accounting is also a foundation for understanding managerial accounting, which uses both financial and non-financial information as a basis for making decisions within an organization with the purpose of equipping decision makers to set and evaluate business goals by determining what information they need to make a particular decision and how to analyze and communicate this information. Managerial accounting information tends to be used internally, for such purposes as budgeting, pricing, and determining production costs. Since the information is generally used internally, you do not see the same need for financial oversight in an organization’s managerial data.

Users of Accounting Information

The ultimate goal of accounting is to provide information that is useful for decision-making. Users of accounting information are generally divided into two categories: internal and external. Internal users are those within an organization who use financial information to make day-to-day decisions. Internal users include managers and other employees who use financial information to confirm past results and help make adjustments for future activities.

External users are those outside of the organization who use the financial information to make decisions or to evaluate an entity’s performance. For example, investors, financial analysts, loan officers, governmental auditors, such as CRA agents, and an assortment of other stakeholders are classified as external users, while still having an interest in an organization’s financial information.

Characteristics, Users, and Sources of Financial Accounting Information

Organizations measure financial performance in monetary terms. Measuring financial performance in monetary terms allows managers to compare the organization’s performance to previous periods, to expectations, and to other organizations or industry standards.

Financial accounting is one of the broad categories in the study of accounting. While some industries and types of organizations have variations in how the financial information is prepared and communicated, accountants generally use the same methodologies—called accounting standards—to prepare the financial information.

Financial information is primarily communicated through financial statements, which include the Income Statement, Statement of Owner’s Equity, Balance Sheet, and Statement of Cash Flows and Disclosures. These financial statements ensure the information is consistent from period to period and generally comparable between organizations. The conventions also ensure that the information provided is both reliable and relevant to the user.

Virtually every activity and event that occurs in a business has an associated cost or value and is known as a transaction. Part of an accountant’s responsibility is to quantify these activities and events.

Accountants often use computerized accounting systems to record and summarize the financial reports, which offer many benefits. The primary benefit of a computerized accounting system is the efficiency by which transactions can be recorded and summarized, and financial reports prepared. In addition, computerized accounting systems store data, which allows organizations to easily extract historical financial information.

Example

Common computerized accounting systems include QuickBooks, which is designed for small organizations, and SAP, which is designed for large and/or multinational organizations. QuickBooks is popular with smaller, less complex entities. It is less expensive than more sophisticated software packages, such as Oracle or SAP, and the QuickBooks skills that accountants developed at previous employers tend to be applicable to the needs of new employers, which can reduce both training time and costs spent on acclimating new employees to an employer’s software system. Also, being familiar with a common software package such as QuickBooks helps provide employment mobility when workers wish to reenter the job market.

While QuickBooks has many advantages, once a company’s operations reach a certain level of complexity, it will need a software package or platform, such as Oracle or SAP, which can be customized to meet the unique informational needs of the entity.

Financial accounting information is mostly historical in nature, although companies and other entities also incorporate estimates into their accounting processes. For example, accountants use estimates to determine bad debt expenses or depreciation expenses for assets that will be used over a multiyear lifetime. That is, accountants prepare financial reports that summarize what has already occurred in an organization. This information provides what is called feedback value. The benefit of reporting what has already occurred is the reliability of the information. Accountants can, with a fair amount of confidence, accurately report the financial performance of the organization related to past activities. The feedback value offered by the accounting information is particularly useful to internal users. That is, reviewing how the organization performed in the past can help managers and other employees make better decisions about and adjustments to future activities.

Financial information has limitations, however, as a predictive tool. Business involves a large amount of uncertainty, and accountants cannot predict how the organization will perform in the future. However, by observing historical financial information, users of the information can detect patterns or trends that may be useful for estimating the company’s future financial performance. Collecting and analyzing a series of historical financial data is useful to both internal and external users. For example, internal users can use financial information as a predictive tool to assess whether the long-term financial performance of the organization aligns with its long-term strategic goals.

External users also use the historical pattern of an organization’s financial performance as a predictive tool. For example, when deciding whether to loan money to an organization, a bank may require a certain number of years of financial statements and other financial information from the organization. The bank will assess the historical performance in order to make an informed decision about the organization’s ability to repay the loan and interest (the cost of borrowing money). Similarly, a potential investor may look at a business’s past financial performance in order to assess whether or not to invest money in the company. In this scenario, the investor wants to know if the organization will provide a sufficient and consistent return on the investment. In these scenarios, the financial information provides value to the process of allocating scarce resources (money). If potential lenders and investors determine the organization is a worthwhile investment, money will be provided, and, if all goes well, those funds will be used by the organization to generate additional value at a rate greater than the alternate uses of the money

Characteristics, Users, and Sources of Managerial Accounting Information

Managerial accounting information is different from financial accounting information in several respects. Accountants use formal accounting standards in financial accounting. These accounting standards are referred to as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and are the common set of rules, standards, and procedures that publicly traded companies must follow when composing their financial statements.

Since most managerial accounting activities are conducted for internal uses and applications, managerial accounting is not prepared using a comprehensive, prescribed set of conventions similar to those required by financial accounting. This is because managerial accountants provide managerial accounting information that is intended to serve the needs of internal, rather than external, users. In fact, managerial accounting information is rarely shared with those outside of the organization. Since the information often includes strategic or competitive decisions, managerial accounting information is often closely protected. The business environment is constantly changing, and managers and decision makers within organizations need a variety of information in order to view or assess issues from multiple perspectives.

Accountants must be adaptable and flexible in their ability to generate the necessary information management decision-making. For example, information derived from a computerized accounting system is often the starting point for obtaining managerial accounting information. But accountants must also be able to extract information from other sources (internal and external) and analyze the data using mathematical, formula-driven software (such as Microsoft Excel).

Management accounting information as a term encompasses many activities within an organization. Preparing a budget, for example, allows an organization to estimate the financial performance for the upcoming year or years and plan for adjustments to scale operations according to the projections. Accountants often lead the budgeting process by gathering information from internal (estimates from the sales and engineering departments, for example) and external (trade groups and economic forecasts, for example) sources. These data are then compiled and presented to decision makers within the organization.

Examples of other decisions that require management accounting information include whether an organization should repair or replace equipment, make products internally or purchase the items from outside vendors, and hire additional workers or use automation.

Example

Filling accounting positions, especially at the CPA level, can be a challenge. Until a few years ago, businesses other than the Big 4 firms basically had two options: post openings on general job platforms such as Monster and Indeed, or go through a staffing agency that charged a hefty fee for finding just the right accounting professional.

Jeff Phillips, a professional recruiter who previously worked for Monster.com, saw the opportunity to create a job site that caters strictly to accounting and bookkeeping jobs and started Accountingfly.com with brothers John and James Hosman. After studying various industries, the founders decided to focus on accounting because of the “massive imbalance” when it came to recruiting for private and public accountants. In their research, the trio found that most of the talent was snapped up by Big 4 accounting firms, leaving other accounting businesses struggling to find the right experienced people to fill key positions.

Despite the record number of students currently majoring in accounting, Phillips discovered the number of graduates taking the CPA exam was declining rapidly, signaling to him that people were losing interest in public accounting jobs. He sees Accountingfly as a way to alert job seekers (and companies) about the good jobs available for new and experienced CPAs outside of the four major players in the accounting field.

As the accounting talent pool evolves, millennials are looking to make their mark in the industry and tend to look for new jobs with organizations that pay competitive salaries, encourage job flexibility, and offer multiple career opportunities for the long haul. Accountingfly attracts both experienced CPAs and college students to its website by providing job boards, webinars, and virtual career fairs. There are more than one million job seekers and 200,000 user profiles on the website. Recently Accountingfly acquired Going Concern, a leading accounting news website that features original content and an insider’s perspective on the people, firms, and culture that shape the accounting profession in this country. According to Phillips, Going Concern has a large, well-informed, highly engaged audience of early-career accountants who could benefit from connecting with accounting firms seeking exceptional talent.

- How does the company’s focus on recruiting accountants and related services give Accountingfly a competitive advantage?

- Do you think Accountingfly’s approach can compete with the Big 4’s expensive and comprehensive recruiting efforts for new accountants? Explain your reasoning.

- How can Accountingfly use its recent acquisition of Going Concern as a recruiting tool for experienced CPAs who desire a different career track? Provide some examples to support your answer.

Sources: “Who We Are,” https://accountingfly.com, accessed August 11, 2017; Ian Welham, “How Accountingfly Is Revolutionizing the Way CPAs Are Hired,” http://cpatrendlines.com, August 5, 2017; “Millennial Businesses to Accounting Firms: Diversify Services, Go Digital and Embrace the Cloud,” https://www.bill.com, May 30, 2017; Carlos Gieseken, “Accountingfly Gains Influence in Industry,” http://www.pnj.com, October 5, 2015; Sherman G. Mohr, Jr., “Meet Jeff Phillips, CEO of Accountingfly. Tech Is Thriving in the Florida Panhandle,” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com, August 24, 2015; “Accountingfly Acquires Going Concern, a Leading Accounting News Publication,” http://www.prweb.com, August 20, 2015.

Typical Accounting Activities and the Role Accountants Play in Identifying, Recording, and Reporting Financial Activities

We can classify organizations into three categories: for profit, governmental, and not for profit. These organizations are similar in several aspects. For example, each of these organizations has inflows and outflows of cash and other resources, such as equipment, furniture, and land, that must be managed. In addition, all of these organizations are formed for a specific purpose or mission and want to use the available resources in an efficient manner—the organizations strive to be good stewards, with the underlying premise of being profitable. Finally, each of the organizations makes a unique and valuable contribution to society. Given the similarities, it is clear that all of these organizations have a need for accounting information and for accountants to provide that information. There are also several differences. The main difference that distinguishes these organizations is the primary purpose or mission of the organization, discussed in the following sections.

For-Profit Businesses

As the name implies, the primary purpose or mission of a for-profit business is to earn a profit by selling goods and services. There are many reasons why a for-profit business seeks to earn a profit. The profits generated by these organizations might be used to create value for employees in the form of pay raises for existing employees as well as hiring additional workers. In addition, profits can be reinvested in the business to create value in the form of research and development, equipment upgrades, facilities expansions, and many other activities that make the business more competitive. Many companies also engage in charitable activities, such as donating money, donating products, or allowing employees to volunteer in their communities. Finally, profits can also be shared with employees in the form of either bonuses or commissions as well as with owners of the business as a reward for the owners’ investment in the business.

In for-profit businesses, accounting information is used to measure the financial performance of the organization and to help ensure that resources are being used efficiently. Efficiently using existing resources allows the businesses to improve quality of the products and services offered, remain competitive in the marketplace, expand when appropriate, and ensure longevity of the business.

For-profit businesses can be further categorized by the types of products or services the business provides. Let’s examine three types of for-profit businesses: manufacturing, retail (or merchandising), and service.

Manufacturing Businesses

A manufacturing business is a for-profit business that is designed to make a specific product or products. Manufacturers specialize in procuring components in the most basic form (often called direct or raw materials) and transforming the components into a finished product that is often drastically different from the original components.

As you think about the products you use every day, you are probably already familiar with products made by manufacturing firms. Examples of products made by manufacturing firms include cars, clothes, cell phones, computers, and many other products that are used every day by millions of consumers.

Retail Businesses

Manufacturing businesses and retail (or merchandising) businesses are similar in that both are for-profit businesses that sell products to consumers. In the case of manufacturing firms, by adding direct labour, manufacturing overhead (such as utilities, rent, and depreciation), and other direct materials, raw components are converted into a finished product that is sold to consumers. A retail business (or merchandising business), on the other hand, is a for-profit business that purchases products (called inventory) and then resells the products without altering them—that is, the products are sold directly to the consumer in the same condition (production state) as purchased.

Cars, clothes, cell phones, and computers are all examples of everyday products that are purchased and sold by retail firms. What distinguishes a manufacturing firm from a retail firm is that in a retail firm, the products are sold in the same condition as when the products were purchased—no further alterations were made on the products.

Service Businesses

As the term implies, service businesses are businesses that provide services to customers. A major difference between manufacturing and retail firms and service firms is that service firms do not have a tangible product that is sold to customers. Instead, a service business provides intangible benefits (services) to customers. A service business can be either a for-profit or a not-for-profit business.

Examples of service-oriented businesses include hotels, cab services, entertainment, and tax preparers. Efficiency is one advantage service businesses offer to their customers. For example, while taxpayers can certainly read the tax code, read the instructions, and complete the forms necessary to file their annual tax returns, many choose to take their tax returns to a person who has specialized training and experience with preparing tax returns. Although it is more expensive to do so, many feel it is a worthwhile investment because the tax professional has invested the time and has the knowledge to prepare the forms properly and in a timely manner. Hiring a tax preparer is efficient for the taxpayer because it allows the taxpayer to file the required forms without having to invest numerous hours researching and preparing the forms.

The accounting conventions for service businesses are similar to the accounting conventions for manufacturing and retail businesses. In fact, the accounting for service businesses is easier in one respect. Because service businesses do not sell tangible products, there is no need to account for products that are being held for sale (inventory).

Governmental Entities

A governmental entity provides services to the general public. Governmental agencies exist at the federal, provincial, and local levels. These entities are funded through the issuance of taxes and other fees.

Accountants working in governmental entities perform the same function as accountants working at for-profit businesses. Accountants help to serve the public interest by providing to the public an accounting for the receipts and disbursements of taxpayer dollars. Governmental leaders are accountable to citizens, and accountants help assure the public that tax dollars are being utilized in an efficient manner.

While the specific accounting used in governmental entities differs from traditional accounting conventions, the goal of providing accurate and unbiased financial information useful for decision-making remains the same, regardless of the type of entity.

Not-for-Profit Entities

A nonprofit (not-for-profit) organization the primary purpose or mission is to serve a particular interest or need in the community. A not-for-profit entity tends to depend on financial longevity based on donations, grants, and revenues generated. It may be helpful to think of not-for-profit entities as “mission-based” entities. It is important to note that not-for-profit entities, while having a primary purpose of serving a particular interest, also have a need for financial sustainability.

An adage in the not-for-profit sector states that “being a not-for-profit organization does not mean it is for-loss.” That is, not-for-profit entities must also ensure that resources are used efficiently, allowing for inflows of resources to be greater than (or, at a minimum, equal to) outflows of resources. This allows the organization to continue and perhaps expand its valuable mission.

Examples of not-for-profit entities are numerous. Food banks have as a primary purpose the collection, storage, and distribution of food to those in need. Charitable foundations have as a primary purpose the provision of funding to local agencies that support specific community needs, such as reading and after-school programs. Many colleges and universities are structured as not-for-profit entities because the primary purpose is to provide education and research opportunities.

While the specific accounting used in not-for profit entities differs slightly from traditional accounting conventions, the goal of providing reliable and unbiased financial information useful for decision-making is vitally important.

Business Stakeholders

The number of decisions we make in a single day is staggering. For example, think about what you had for breakfast this morning. What pieces of information factored into that decision? A short list might include the foods that were available in your home, the amount of time you had to prepare and eat the food, and what sounded good to eat this morning. Let’s say you do not have much food in your home right now because you are overdue on a trip to the grocery store. Deciding to grab something at a local restaurant involves an entirely new set of choices. Can you think of some of the factors that might influence the decision to grab a meal at a local restaurant?

It is no different when it comes to financial decisions. Decision makers rely on unbiased, relevant, and timely financial information in order to make sound decisions. In this context, the term stakeholder refers to a person or group who relies on financial information to make decisions, since they often have an interest in the economic viability of an organization or business. Stakeholders may be stockholders, creditors, governmental and regulatory agencies, customers, management and other employees, and various other parties and entities.

What is a Stockholder?

A stockholder is an owner of stock in a business. Owners are called stockholders because in exchange for cash, they are given an ownership interest in the business, called stock. Stock is sometimes referred to as “shares.” Historically, stockholders received paper certificates reflecting the number of stocks owned in the business. Now, many stock transactions are recorded electronically.

Recall that organizations can be classified as for-profit, governmental, or not-for-profit entities. Stockholders are associated with for-profit businesses. While governmental and not-for-profit entities have constituents, there is no direct ownership associated with these entities.

For-profit businesses are organized into three categories: manufacturing, retail (or merchandising), and service. Another way to categorize for-profit businesses is based on the availability of the company stock. A publicly traded company is one whose stock is traded (bought and sold) on an organized stock exchange such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation (NASDAQ) system. Most large, recognizable companies are publicly traded, meaning the stock is available for sale on these exchanges. A privately held company, in contrast, is one whose stock is not available to the general public.

Whether the stock is owned by a publicly traded or privately held company, owners use financial information to make decisions. Owners use the financial information to assess the financial performance of the business and make decisions such as whether or not to purchase additional stock, sell existing stock, or maintain the current level of stock ownership.

What is Finance?

Finance is an imprecise generalization that may encompass several branches of economics, law and general know-how on managing valuable assets, from simple currency and property to bonds and other more complex financial instruments. More specifically, one can state that through financial analysis and decisions, planned actions can be taken regarding the collection and use of those assets to optimize financial resources toward the objectives of an organization (states, companies and businesses) or individual.

Types of finance:

- Overdraft

- Bank term loans

- Asset-based finance

- Receivables Finance

- Invoice discounting

- Angel funding

- Venture capital

- Personal resources.

Financial Investments

In its broadest meaning, to invest means to give up something in the present for something of greater value in the future. Investments, what we invest in, can differ greatly. They may range from lottery tickets and burial plots to municipal bonds and corporate stocks. It is helpful to organize these investments into two general categories: real and financial. Capital, or real, investments involve the exchange of money for nonfinancial investments that produce services such as storage services from buildings, pulling services from tractors, and growing services from land. Financial investments involve the exchange of money in the present for a future money payment. Financial investments include time deposits, bonds, and stocks.

The market in which financial investments are traded is called the securities market or financial market. Activities in the financial markets are facilitated by brokers, dealers, and financial intermediaries. A broker acts as an agent for investors in the securities markets. The securities broker brings two parties together to obtain the best possible terms for his or her client and is compensated by a commission. A dealer, in contrast to a broker, buys and sells securities for his or her own account. Thus, a dealer also becomes an investor. Similarly, financial intermediaries (e.g., banks, investment firms, and insurance companies) play important roles in the flow of funds from savers to ultimate investors. The intermediary acquires ownership of funds loaned or invested by savers, modifies the risk and liquidity of these funds, and then either loans the funds to individual borrowers or invests in various types of financial assets.

Time Is Money

The fact that you have to choose a career at an early stage in your financial life cycle isn’t the only reason that you need to start early on your financial planning. Let’s assume, for instance, that it’s your eighteenth birthday and that on this day you take possession of $10,000 that your grandparents put in trust for you. You could, of course, spend it; in particular, it would probably cover the cost of flight training for a private pilot’s license—something you’ve always wanted but were convinced that you couldn’t afford right away. Your grandfather, of course, suggests that you put it into some kind of savings account. If you just wait until you finish college, he says, and if you can find a savings plan that pays 5 percent interest, you’ll have the $10,000 plus about another $2,000 for something else or to invest.

The total amount you’ll have— $12,000—piques your interest. If that $10,000 could turn itself into $12,000 after sitting around for four years, what would it be worth if you actually held on to it until you did retire—say, at age sixty-five? A quick trip to the Internet to find a compound-interest calculator informs you that, forty-seven years later, your $10,000 will have grown to $104,345 (assuming a 5 percent interest rate). That’s not really enough for retirement, but it would be a good start. On the other hand, what if that four years in college had paid off the way you planned, so that once you get a good job you’re able to add, say, another $10,000 to your retirement savings account every year until age sixty-five? At that rate, you’ll have amassed a nice little nest egg of slightly more than $1.6 million.

Compound Interest

In your efforts to appreciate the potential of your $10,000 to multiply itself, you have acquainted yourself with two of the most important concepts in finance. As we’ve already indicated, one is the principle of compound interest, which refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest.

Let’s say, for example, that you take your grandfather’s advice and invest your $10,000 (your principal) in a savings account at an annual interest rate of 5 percent. Over the course of the first year, your investment will earn $500 in interest and grow to $10,500. If you now reinvest the entire $10,500 at the same 5 percent annual rate, you’ll earn another $525 in interest, giving you a total investment at the end of year 2 of $11,025. And so forth. And that’s how you can end up with $81,496.67 at age sixty-five.

Time Value of Money

You’ve also encountered the principle of the time value of money—the principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future. If there’s one thing that you may have noticed in life, it’s the fact that most people prefer to consume now rather than in the future. If you borrow money from me, it’s because you can’t otherwise buy something that you want at the present time. If I lend it to you, I must forego my opportunity to purchase something I want at the present time. I will do so only if I can get some compensation for making that sacrifice, and that’s why I’m going to charge you interest. And you’re going to pay the interest because you need the money to buy what you want to buy now. How much interest should we agree on? In theory, it could be just enough to cover the cost of my lost opportunity, but there are, of course, other factors. Inflation, for example, will have eroded the value of my money by the time I get it back from you. In addition, while I would be taking no risk in loaning money to the U.S. government, I am taking a risk in lending it to you. Our agreed-on rate will reflect such factors.

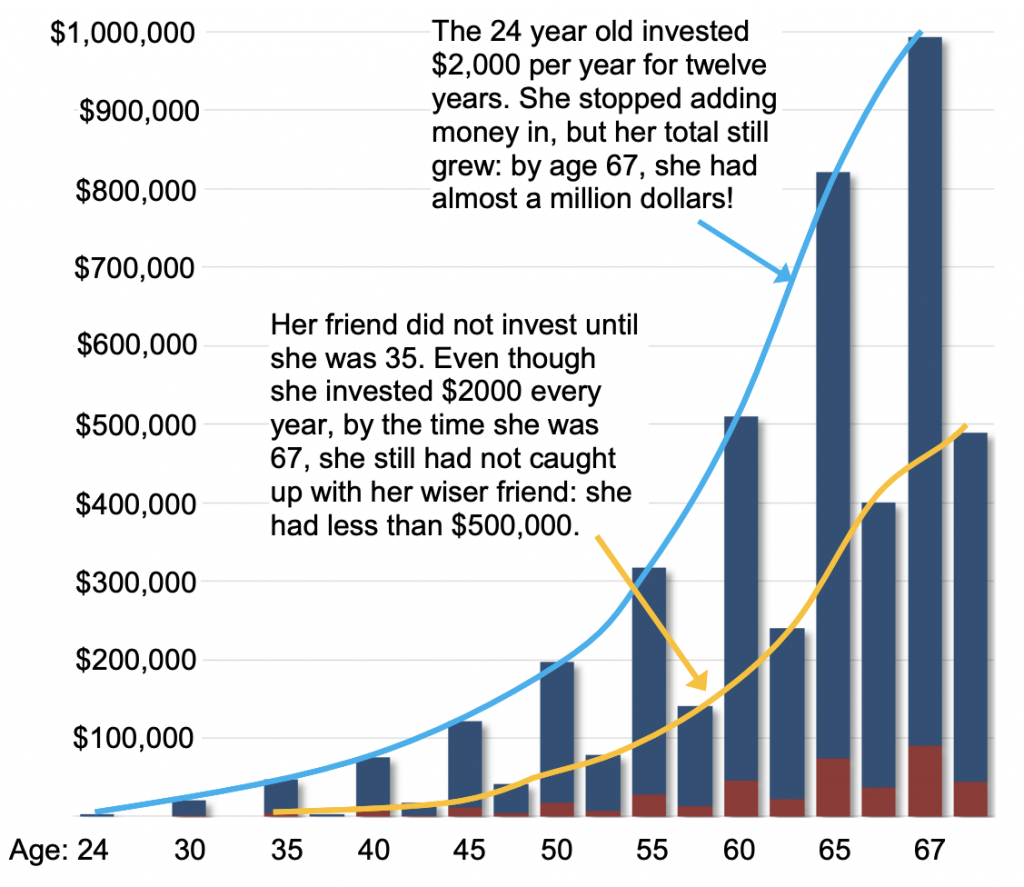

Finally, the time value of money principle also states that a dollar received today starts earning interest sooner than one received tomorrow. Let’s say, for example, that you receive $2,000 in cash gifts when you graduate from college. At age twenty-three, with your college degree in hand, you get a decent job and don’t have an immediate need for that $2,000. So you put it into an account that pays 10 percent compounded and you add another $2,000 ($167 per month) to your account every year for the next eleven years. The blue line in the graph belows hows how much your account will earn each year and how much money you’ll have at certain ages between twenty-four and sixty-seven.

As you can see, you’d have nearly $52,000 at age thirty-six and a little more than $196,000 at age fifty; at age sixty-seven, you’d be just a bit short of $1 million. The yellow line in the graph shows what you’d have if you hadn’t started saving $2,000 a year until you were age thirty-six. As you can also see, you’d have a respectable sum at age sixty-seven—but less than half of what you would have accumulated by starting at age twenty-three. More important, even to accumulate that much, you’d have to add $2,000 per year for a total of thirty-two years, not just twelve.

Here’s another way of looking at the same principle. Suppose that you’re twenty years old, don’t have $2,000, and don’t want to attend college full-time. You are, however, a hard worker and a conscientious saver, and one of your financial goals is to accumulate a $1 million retirement nest egg. As a matter of fact, if you can put $33 a month into an account that pays 12 percent interest compounded, you can have your $1 million by age sixty-seven. That is, if you start at age twenty. If you wait until you’re twenty-one to start saving, you’ll need $37 a month. If you wait until you’re thirty, you’ll have to save $109 a month, and if you procrastinate until you’re forty, the ante goes up to $366 a month. Unfortunately in today’s low interest rate environment, finding 10 to 12% return is not likely. Nevertheless, these figures illustrate the significant benefit of saving early.

Here’s another way of looking at the same principle. Suppose that you’re twenty years old, don’t have $2,000, and don’t want to attend college full-time. You are, however, a hard worker and a conscientious saver, and one of your financial goals is to accumulate a $1 million retirement nest egg. As a matter of fact, if you can put $33 a month into an account that pays 12 percent interest compounded, you can have your $1 million by age sixty-seven. That is, if you start at age twenty. If you wait until you’re twenty-one to start saving, you’ll need $37 a month. If you wait until you’re thirty, you’ll have to save $109 a month, and if you procrastinate until you’re forty, the ante goes up to $366 a month. Unfortunately in today’s low interest rate environment, finding 10 to 12% return is not likely. Nevertheless, these figures illustrate the significant benefit of saving early.

The reason should be fairly obvious: a dollar saved today not only starts earning interest sooner than one saved tomorrow (or ten years from now) but also can ultimately earn a lot more money in the long run. Starting early means in your twenties—early in stage 1 of your financial life cycle. As one well-known financial advisor puts it, “If you’re in your 20s and you haven’t yet learned how to delay gratification, your life is likely to be a constant financial struggle.”

Suppose you want to save or invest – do you know how or where to do so? You probably know that your branch bank can open a savings account for you, but interest rates on such accounts can be pretty unattractive. Investing in individual stocks or bonds can be risky, and usually require a level of funds available that most students don’t have. In those cases, mutual funds can be quite interesting. A mutual fund is a professionally managed investment program in which shareholders buy into a group of diversified holdings, such as stocks and bonds. Companies like Vanguard and Fidelity offer a range of investment options including indexed funds, which track with well-known indices such as the Standard & Poors 500, a.k.a. the S&P 500. Minimum investment levels in such funds can actually be within the reach of many students, and the funds accept electronic transfers to make investing more convenient. We’ll leave a more detailed discussion of investment vehicles to your more advanced courses.

Key Takeaways

1) Accounting is the process of measuring and summarizing business activities, interpreting financial information, and communicating the results to management and other decision makers

2) Managerial accounting deals with information produced for internal users, while financial accounting deals with external reporting.

3) The income statement captures sales and expenses over a period of time and shows how much a firm made or lost in that period.

4) The balance sheet reflects the financial position of a firm at a given point in time, including its assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity. It is based on the following equation: assets – liabilities = owner’s equity.

5) Breakeven analysis is a technique used to determine the level of sales needed to break even—to operate at a sales level at which you have neither profit nor loss.

Exercises

-

As the controller of a medium-sized financial services company, you take pride in the accounting and internal control systems you have developed for the company. You and your staff have kept up with changes in the accounting industry and been diligent in updating the systems to meet new accounting standards. Your outside auditor, which has been reviewing the company’s books for 15 years, routinely complimented you on your thorough procedures.

The passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, with its emphasis on testing internal control systems, initiated several changes. You have studied the law and made adjustments to ensure you comply with the regulations, even though it has created additional work. Your auditors, however, have chosen to interpret SOX very aggressively—too much so, in your opinion. The auditors have recommended that you make costly improvements to your systems and also enlarged the scope of the audit process, raising their fees. When you question the partner in charge, he explains that the complexity of the law means that it is open to interpretation and it is better to err on the side of caution than risk noncompliance. You are not pleased with this answer, as you believe that your company is in compliance with SOX, and consider changing auditors.

Using a web search tool, locate articles about this topic and then write responses to the following questions. Be sure to support your arguments and cite your sources.

Ethical Dilemma: Should you change auditors because your current one is too stringent in applying the Sarbanes-Oxley Act? What other steps could you take to resolve this situation?

Sources: Loren Kasuske, “The 4 Biggest Pros and Cons of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act,” https://ktconnections.com, June 8, 2017; Terry Sheridan, “Financial Services Spend More than $1M Annually on SOX,” https://www.accountingweb.com, August 2, 2016; “Sarbanes-Oxley Is Paying Off for Companies Despite Increased Costs and Hours, Protiviti Survey Finds,” http://www.prnewswire.com, June 2, 2016; Daniel Kim, “Top 3 Ways to Reduce SOX Compliance Costs,” https://www.soxhub.com, December 14, 2015.

-

Use the internet and business publications to research how companies and accounting firms are implementing the provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. What are the major concerns they face? What rules have other organizations issued that relate to Act compliance? Summarize your findings.

-

Team Activity Two years ago, Rebecca Mardon started a computer consulting business, Mardon Consulting Associates. Until now, she has been the only employee, but business has grown enough to support hiring an administrative assistant and another consultant this year. Before she adds staff, however, she wants to hire an accountant and computerize her financial recordkeeping. Divide the class into small groups, assigning one person to be Rebecca and the others to represent members of a medium-sized accounting firm. Rebecca should think about the type of financial information systems her firm requires and develop a list of questions for the firm. The accountants will prepare a presentation making recommendations to her as well as explaining why their firm should win the account.

Attributions

Personal Finance by Carol Yacht licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Principles of Accounting by Mitchell Franklin (LeMoyne College) licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Accounting Principles: A Business Perspective by Roger H. Hermanson, James D. Edwards, Michael W. Maher licensed under CC BY

Managerial Accounting by Kurt Heisinger and Joe Hoyle licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Risk Management for Enterprises and Individuals by Etti Baranoff, Patrick Lee Brokett and Yehuda Kahane licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Fundamentals of Business: Canadian Edition by Pamplin College of Business and Virgina Tech Libraries is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA, except where otherwise noted

Introduction to Business by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0

is the process of measuring and summarizing business activities, interpreting financial information, and communicating the results to management and other decision makers

Accounting that focuses on preparing external financial reports that are used by outsiders such as lenders, suppliers, investors, and government agencies to assess the financial strength of a business.

deals with information produced for internal users, while financial accounting deals with external reporting

captures sales and expenses over a period of time and shows how much a firm made or lost in that period.

reflects the financial position of a firm at a given point in time, including its assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity. It is based on the following equation: assets – liabilities = owner’s equity.

What a firm owes to its creditors; also called debts.

Things of value owned by a firm.