5.1 – Biological Energy

|

5.1. List and briefly explain different types of energy relevant for biology. |

Cell’s metabolism and energy

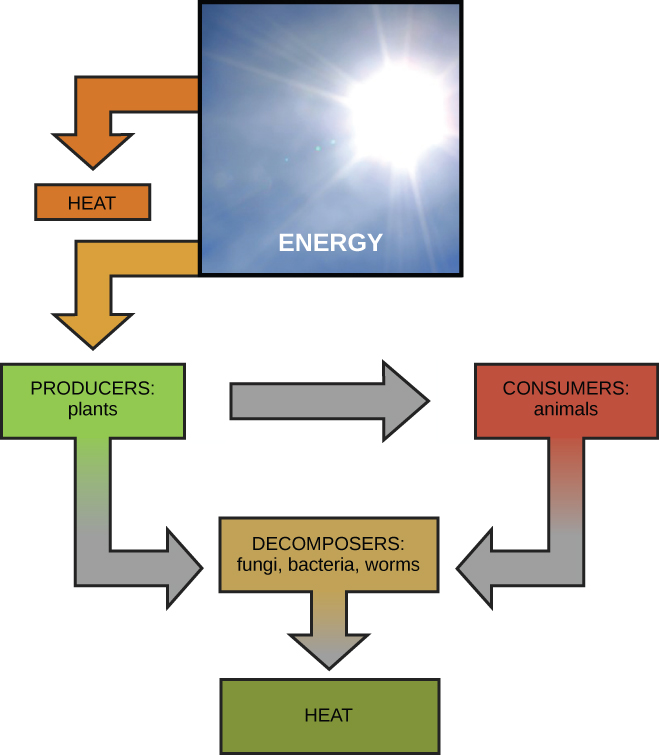

Scientists use the term bioenergetics to describe the concept of energy flow (Figure 5.1) through living systems, such as cells. Cellular processes such as the building and breaking down of complex molecules occur through stepwise chemical reactions. Some of these chemical reactions are spontaneous and release energy, whereas others require energy to proceed. Just as living things must continually consume food to replenish their energy supplies, cells must continually produce more energy to replenish that used by the many energy-requiring chemical reactions that constantly take place. Together, all of the chemical reactions that take place inside cells, including those that consume or generate energy, are referred to as the cell’s metabolism.

Metabolic pathways

Consider the metabolism of sugar. This is a classic example of one of the many cellular processes that use and produce energy. Living things consume sugars as a major energy source because sugar molecules have a great deal of energy stored within their bonds. For the most part, photosynthesizing organisms like plants produce these sugars. During photosynthesis, plants use energy (originally from sunlight) to convert carbon dioxide gas (CO2) into sugar molecules (like glucose: C6H12O6). They consume carbon dioxide and produce oxygen as a waste product. This reaction is summarized as:

6CO2 + 6H2O + energy ——-> C6H12O6+ 6O2

Because this process involves synthesizing an energy-storing molecule, it requires energy input to proceed. During the light reactions of photosynthesis, energy is provided by a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the primary energy currency of all cells. Just as the dollar is used as currency to buy goods, cells use molecules of ATP as energy currency to perform immediate work. In contrast, energy-storage molecules such as glucose are consumed only to be broken down to use their energy. The reaction that harvests the energy of a sugar molecule in cells requiring oxygen to survive can be summarized by the reverse reaction to photosynthesis. In this reaction, oxygen is consumed and carbon dioxide is released as a waste product. The reaction is summarized as:

C6H12O6 + 6O2 ——> 6CO2 + 6H2O + energy

Both of these reactions involve many steps.

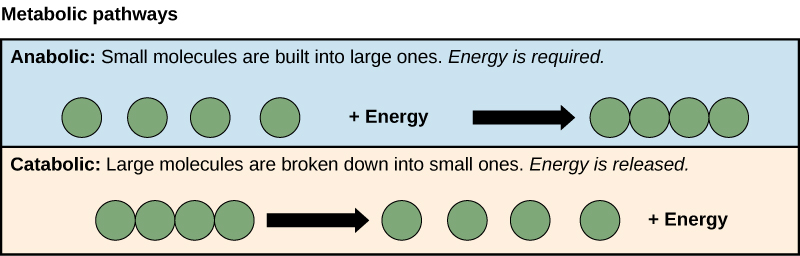

The processes of making and breaking down sugar molecules illustrate two examples of metabolic pathways. A metabolic pathway is a series of chemical reactions that takes a starting molecule and modifies it, step-by-step, through a series of metabolic intermediates, eventually yielding a final product. In the example of sugar metabolism, the first metabolic pathway synthesized sugar from smaller molecules, and the other pathway broke sugar down into smaller molecules. These two opposite processes—the first requiring energy and the second producing energy—are referred to as anabolic pathways (building polymers) and catabolic pathways (breaking down polymers into their monomers), respectively. Consequently, metabolism is composed of synthesis (anabolism) and degradation (catabolism) (Figure 5.2).

It is important to know that the chemical reactions of metabolic pathways do not take place on their own. Each reaction step is facilitated, or catalyzed, by a protein called an enzyme. Enzymes are important for catalyzing all types of biological reactions—those that require energy as well as those that release energy.

Energy

Thermodynamics refers to the study of energy and energy transfer involving physical matter. The matter relevant to a particular case of energy transfer is called a system, and everything outside of that matter is called the surroundings. For instance, when heating a pot of water on the stove, the system includes the stove, the pot, and the water. Energy is transferred within the system (between the stove, pot, and water). There are two types of systems: open and closed. In an open system, energy can be exchanged with its surroundings. The stovetop system is open because heat can be lost to the air. A closed system cannot exchange energy with its surroundings.

Biological organisms are open systems. Energy is exchanged between them and their surroundings as they use energy from the sun to perform photosynthesis or consume energy-storing molecules and release energy to the environment by doing work and releasing heat. Like all things in the physical world, energy is subject to physical laws. The laws of thermodynamics govern the transfer of energy in and among all systems in the universe.

In general, energy is defined as the ability to do work or to create some kind of change. Energy exists in different forms. For example, electrical energy, light energy, and heat energy are all different types of energy. To appreciate the way energy flows into and out of biological systems, it is important to understand two of the physical laws that govern energy.

Thermodynamics

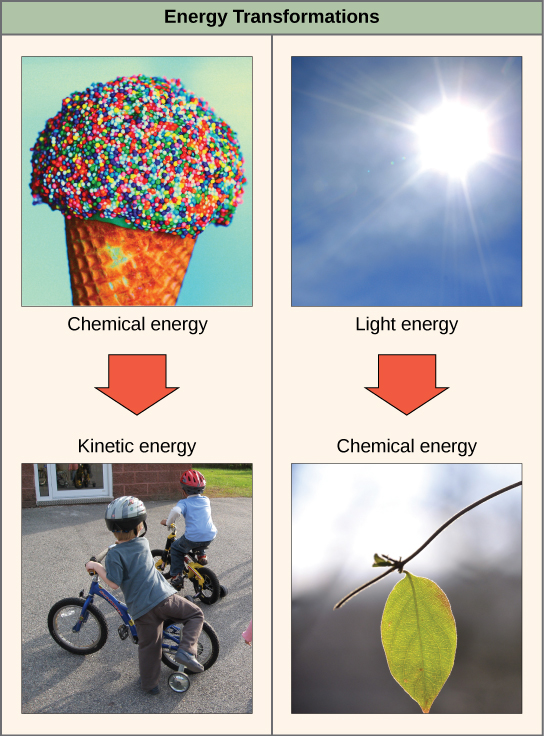

The first law of thermodynamics states that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant and conserved. In other words, there has always been, and always will be, exactly the same amount of energy in the universe. Energy exists in many different forms. According to the first law of thermodynamics, energy may be transferred from place to place or transformed into different forms, but it cannot be created or destroyed. The transfers and transformations of energy take place around us all the time. Light bulbs transform electrical energy into light and heat energy. Gas stoves transform chemical energy from natural gas into heat energy. Plants perform one of the most biologically useful energy transformations on earth: that of converting the energy of sunlight to chemical energy stored within organic molecules (Figure 5.2). Some examples of energy transformations are shown in Figure 5.3.

The challenge for all living organisms is to obtain energy from their surroundings in forms that they can transfer or transform into usable energy to do work. Living cells have evolved to meet this challenge. Chemical energy stored within organic molecules such as sugars and fats is transferred and transformed through a series of cellular chemical reactions into energy within molecules of ATP. Energy in ATP molecules is easily accessible to do work. Examples of the types of work that cells need to do include building complex molecules, transporting materials, powering the motion of cilia or flagella, and contracting muscle fibers to create movement.

A living cell’s primary tasks of obtaining, transforming, and using energy to do work may seem simple. However, the second law of thermodynamics explains why these tasks are harder than they appear. All energy transfers and transformations are never completely efficient. In every energy transfer, some amount of energy is lost in a form that is unusable. In most cases, this form is heat energy. Thermodynamically, heat energy is defined as the energy transferred from one system to another that is not work. For example, when a light bulb is turned on, some of the energy being converted from electrical energy into light energy is lost as heat energy. Likewise, some energy is lost as heat energy during cellular metabolic reactions.

An important concept in physical systems is that of order and disorder. The more energy that is lost by a system to its surroundings, the less ordered and more random the system is. Scientists refer to the measure of randomness or disorder within a system as entropy. High entropy means high disorder and low energy. Molecules and chemical reactions have varying entropy as well. For example, entropy increases as molecules at a high concentration in one place diffuse and spread out. The second law of thermodynamics says that energy will always be lost as heat in energy transfers or transformations.

Living things are highly ordered, requiring constant energy input to be maintained in a state of low entropy.

Potential and kinetic energy

When an object is in motion, there is energy associated with that object. Think of a wrecking ball. Even a slow-moving wrecking ball can do a great deal of damage to other objects. The energy associated with objects in motion is called kinetic energy (Figure 5.4). A speeding bullet, a walking person, and the rapid movement of molecules in the air (which produces heat) all have kinetic energy.

Now, what if that same motionless wrecking ball is lifted two stories above ground with a crane? If the suspended wrecking ball is unmoving, is there energy associated with it? The answer is yes. The energy that was required to lift the wrecking ball did not disappear but is now stored in the wrecking ball by virtue of its position and the force of gravity acting on it. This type of energy is called potential energy (Figure 5.4). If the ball were to fall, the potential energy would be transformed into kinetic energy until all of the potential energy was exhausted when the ball rested on the ground. Wrecking balls also swing like a pendulum; through the swing, there is a constant change of potential energy (highest at the top of the swing) to kinetic energy (highest at the bottom of the swing). Other examples of potential energy include the energy of water held behind a dam or a person about to skydive out of an airplane.

Potential energy is not only associated with the location of matter, but also with the structure of matter. Even a spring on the ground has potential energy if it is compressed; so does a rubber band that is pulled taut. On a molecular level, the bonds that hold the atoms of molecules together exist in a particular structure that has potential energy. Remember that anabolic cellular pathways require energy to synthesize complex molecules from simpler ones and catabolic pathways release energy when complex molecules are broken down. The fact that energy can be released by the breakdown of certain chemical bonds implies that those bonds have potential energy. In fact, there is potential energy stored within the bonds of all the food molecules we eat, which is eventually harnessed for use. This is because these bonds can release energy when broken. The type of potential energy that exists within chemical bonds, and is released when those bonds are broken, is called chemical energy. Chemical energy is responsible for providing living cells with energy from food. The release of energy occurs when the molecular bonds within food molecules are broken.

|

Watch this video about kilocalories to help you connect with cellular respiration and energy information you read about in this section of Chapter 5. |

|

Visit this site and select “Pendulum” from the “Work and Energy” menu to see the shifting kinetic and potential energy of a pendulum in motion. |

Free and activation energy

After learning that chemical reactions release energy when energy-storing bonds are broken, an important next question is the following: How is the energy associated with these chemical reactions quantified and expressed? How can the energy released from one reaction be compared to that of another reaction? A measurement of free energy is used to quantify these energy transfers. Recall that according to the second law of thermodynamics, all energy transfers involve the loss of some amount of energy in an unusable form such as heat. Free energy specifically refers to the energy associated with a chemical reaction that is available after the losses are accounted for. In other words, free energy is usable energy or energy that is available to do work.

If energy is released during a chemical reaction, then the change in free energy, signified as ∆G (delta G) will be a negative number. A negative change in free energy also means that the products of the reaction have less free energy than the reactants because they release some free energy during the reaction. Reactions that have a negative change in free energy and consequently release free energy are called exergonic reactions. Think: exergonic means energy is exiting the system. These reactions are also referred to as spontaneous reactions, and their products have less stored energy than the reactants. An important distinction must be drawn between the term spontaneous and the idea of a chemical reaction occurring immediately. Contrary to the everyday use of the term, a spontaneous reaction is not one that suddenly or quickly occurs. The rusting of iron is an example of a spontaneous reaction that occurs slowly, little by little, over time.

If a chemical reaction absorbs energy rather than releases energy on balance, then the ∆G for that reaction will be a positive value. In this case, the products have more free energy than the reactants. Thus, the products of these reactions can be thought of as energy-storing molecules. These chemical reactions are called endergonic reactions and they are non-spontaneous. An endergonic reaction will not take place on its own without the addition of free energy.

|

Question 5.1

Look at each of the processes shown in Figure 5.5 and decide if it is endergonic or exergonic. |

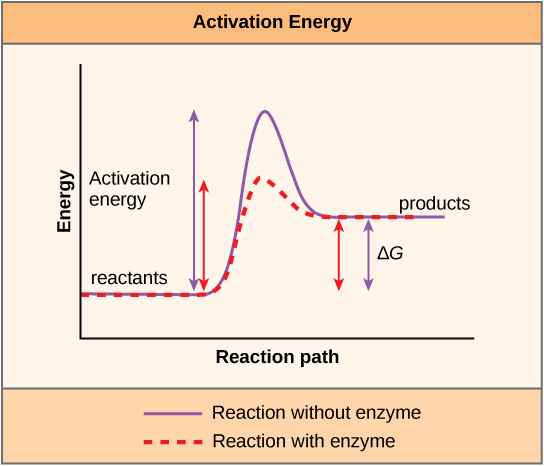

There is another important concept that must be considered regarding endergonic and exergonic reactions. Exergonic reactions require a small amount of energy input to get going before they can proceed with their energy-releasing steps. These reactions have a net release of energy, but still, require some energy input in the beginning. This small amount of energy input necessary for all chemical reactions to occur is called the activation energy.

Enzymes

A substance that helps a chemical reaction to occur is called a catalyst, and the molecules that catalyze biochemical reactions are called enzymes. Most enzymes are proteins and perform the critical task of lowering the activation energies of chemical reactions inside the cell. Most of the reactions critical to a living cell happen too slowly at normal temperatures to be of any use to the cell. Without enzymes to speed up these reactions, life could not persist. Enzymes do this by binding to the reactant molecules and holding them in such a way as to make the chemical bond-breaking and -forming processes take place more easily. It is important to remember that enzymes do not change whether a reaction is exergonic (spontaneous) or endergonic. This is because they do not change the free energy of the reactants or products. They only reduce the activation energy required for the reaction to go forward (Figure 5.6). In addition, an enzyme itself is unchanged by the reaction it catalyzes. Once one reaction has been catalyzed, the enzyme is able to participate in other reactions.

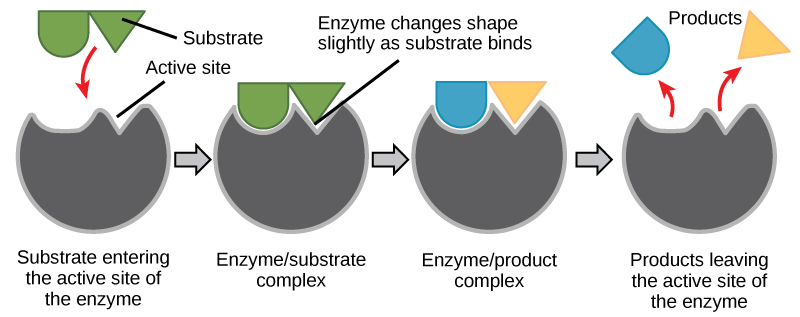

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are called the enzyme’s substrates. There may be one or more substrates, depending on the particular chemical reaction. In some reactions, a single reactant substrate is broken down into multiple products. In others, two substrates may come together to create one larger molecule. Two reactants might also enter a reaction and both become modified, but they leave the reaction as two products. The location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site. The active site is where the “action” happens. Since enzymes are proteins, there is a unique combination of amino acid side chains within the active site. Each side chain is characterized by different properties. They can be large or small, weakly acidic or basic, hydrophilic or hydrophobic, positively or negatively charged, or neutral. The unique combination of side chains creates a very specific chemical environment within the active site. This specific environment is suited to bind to one specific chemical substrate (or substrates).

Active sites are subject to influences of the local environment. Increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme-catalyzed or otherwise. However, temperatures outside of an optimal range reduce the rate at which an enzyme catalyzes a reaction. Hot temperatures will eventually cause enzymes to denature, an irreversible change in the three-dimensional shape and therefore the function of the enzyme. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH and salt concentration range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH, and salt concentrations can cause enzymes to denature.

For many years, scientists thought that enzyme-substrate binding took place in a simple “lock and key” fashion. This model asserted that the enzyme and substrate fit together perfectly in one instantaneous step. However, current research supports a model called induced fit (Figure 5.7). The induced-fit model expands on the lock-and-key model by describing a more dynamic binding between enzyme and substrate. As the enzyme and substrate come together, their interaction causes a mild shift in the enzyme’s structure that forms an ideal binding arrangement between enzyme and substrate.

|

View an animation of induced fit. |

When an enzyme binds its substrate, an enzyme-substrate complex is formed. This complex lowers the activation energy of the reaction and promotes its rapid progression in one of the multiple possible ways. On a basic level, enzymes promote chemical reactions that involve more than one substrate by bringing the substrates together in an optimal orientation for reaction. Another way in which enzymes promote the reaction of their substrates is by creating an optimal environment within the active site for the reaction to occur. The chemical properties that emerge from the particular arrangement of amino acid R groups within an active site create the perfect environment for an enzyme’s specific substrates to react.

The enzyme-substrate complex can also lower activation energy by compromising the bond structure so that it is easier to break. Finally, enzymes can also lower activation energies by taking part in the chemical reaction itself. In these cases, it is important to remember that the enzyme will always return to its original state upon the completion of the reaction. One of the hallmark properties of enzymes is that they remain ultimately unchanged by the reactions they catalyze. After an enzyme has catalyzed a reaction, it releases its product(s) and can catalyze a new reaction.

It would seem ideal to have a scenario in which all of an organism’s enzymes existed in abundant supply and functioned optimally under all cellular conditions, in all cells, at all times. However, a variety of mechanisms ensures that this does not happen. Cellular needs and conditions constantly vary from cell to cell and change within individual cells over time. The required enzymes of stomach cells differ from those of fat storage cells, skin cells, blood cells, and nerve cells. Furthermore, a digestive organ cell works much harder to process and break down nutrients during the time that closely follows a meal compared with many hours after a meal. As these cellular demands and conditions vary, so must the amounts and functionality of different enzymes.

Since the rates of biochemical reactions are controlled by activation energy, and enzymes lower and determine activation energies for chemical reactions, the relative amounts and functioning of the variety of enzymes within a cell ultimately determine which reactions will proceed and at what rates. This determination is tightly controlled in cells. In certain cellular environments, enzyme activity is partly controlled by environmental factors like pH, temperature, salt concentration, and, in some cases, cofactors or coenzymes.

Enzymes can also be regulated in ways that either promote or reduce enzyme activity. There are many kinds of molecules that inhibit or promote enzyme function, and various mechanisms by which they do so. In some cases of enzyme inhibition, an inhibitor molecule is similar enough to a substrate that it can bind to the active site and simply block the substrate from binding. When this happens, the enzyme is inhibited through competitive inhibition, because an inhibitor molecule competes with the substrate for binding to the active site.

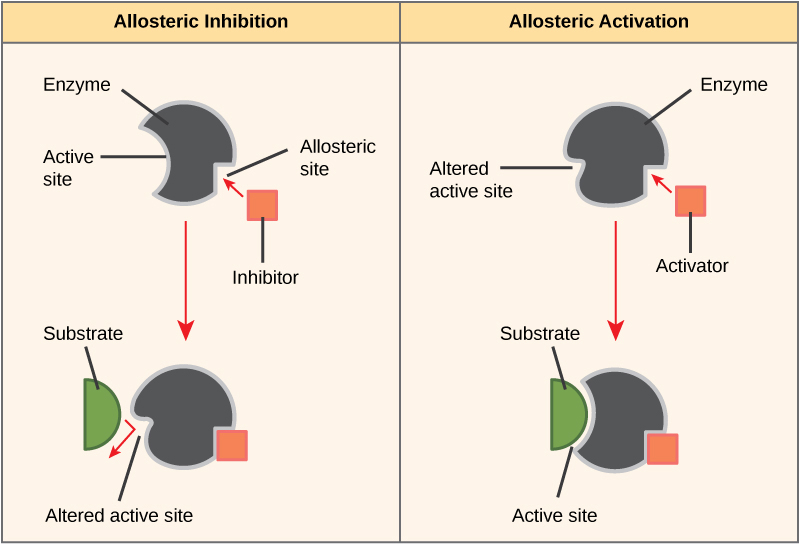

On the other hand, in noncompetitive inhibition, an inhibitor molecule binds to the enzyme in a location other than the active site, called an allosteric site, but still manages to block substrate binding to the active site. Some inhibitor molecules bind to enzymes in a location where their binding induces a conformational change that reduces the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. This type of inhibition is called allosteric inhibition (Figure 5.8). Most allosterically regulated enzymes are made up of more than one polypeptide, meaning that they have more than one protein subunit. When an allosteric inhibitor binds to a region on an enzyme, all active sites on the protein subunits are changed slightly such that they bind their substrates with less efficiency. There are allosteric activators as well as inhibitors. Allosteric activators bind to locations on an enzyme away from the active site, inducing a conformational change that increases the affinity of the enzyme’s active site(s) for its substrate(s) (Figure 5.8).

Enzymes are key components of metabolic pathways. Understanding how enzymes work and how they can be regulated are key principles behind the development of many of the pharmaceutical drugs on the market today. Biologists working in this field collaborate with other scientists to design drugs (Figure 5.9).

Consider statins for example—statins is the name given to one class of drugs that can reduce cholesterol levels. These compounds are inhibitors of the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which is the enzyme that synthesizes cholesterol from lipids in the body. By inhibiting this enzyme, the level of cholesterol synthesized in the body can be reduced. Similarly, acetaminophen, popularly marketed under the brand name Tylenol, is an inhibitor of the enzyme cyclooxygenase. While it is used to provide relief from fever and inflammation (pain), its mechanism of action is still not completely understood.

How are drugs discovered? One of the biggest challenges in drug discovery is identifying a drug target. A drug target is a molecule that is literally the target of the drug. In the case of statins, HMG-CoA reductase is the drug target. Drug targets are identified through painstaking research in the laboratory. Identifying the target alone is not enough; scientists also need to know how the target acts inside the cell and which reactions go awry in the case of a disease. Once the target and the pathway are identified, then the actual process of drug design begins. In this stage, chemists and biologists work together to design and synthesize molecules that can block or activate a particular reaction. However, this is only the beginning: If and when a drug prototype is successful in performing its function, then it is subjected to many tests from in vitro experiments to clinical trials before it can get approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be on the market.

Many enzymes do not work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific non-protein helper molecules. They may bond either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds, or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Binding to these molecules promotes optimal shape and function of their respective enzymes. Two examples of these types of helper molecules are cofactors and coenzymes. Cofactors are inorganic ions such as ions of iron and magnesium. Coenzymes are organic helper molecules, those with a basic atomic structure made up of carbon and hydrogen. Like enzymes, these molecules participate in reactions without being changed themselves and are ultimately recycled and reused. Vitamins are the source of coenzymes. Some vitamins are the precursors of coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes. Vitamin C is a direct coenzyme for multiple enzymes that take part in building the important connective tissue, collagen. Therefore, enzyme function is, in part, regulated by the abundance of various cofactors and coenzymes, which may be supplied by an organism’s diet or, in some cases, produced by the organism.

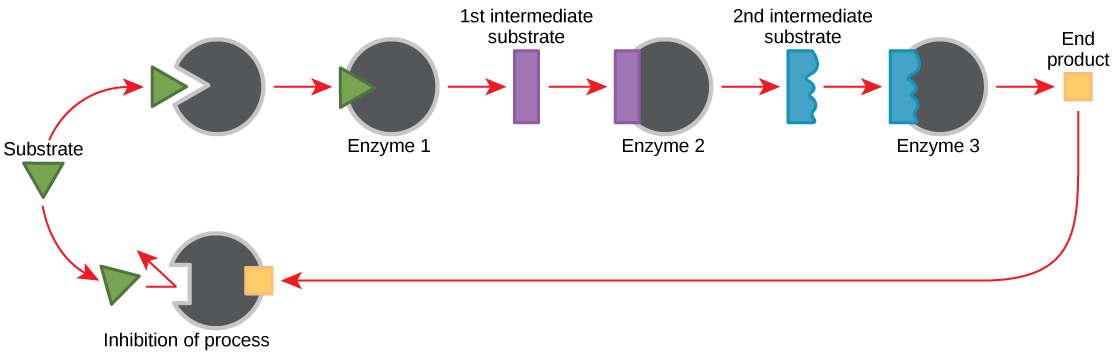

Feedback inhibition in metabolic pathways

Molecules can regulate enzyme function in many ways. The major question remains, however: What are these molecules and where do they come from? Some are cofactors and coenzymes, as you have learned. What other molecules in the cell provide enzymatic regulation such as allosteric modulation and competitive and non-competitive inhibition? Perhaps the most relevant sources of regulatory molecules, with respect to enzymatic cellular metabolism, are the products of the cellular metabolic reactions themselves. In a most efficient and elegant way, cells have evolved to use the products of their own reactions for feedback inhibition of enzyme activity. Feedback inhibition involves the use of a reaction product to regulate its own further production (Figure 5.10). The cell responds to an abundance of the products by slowing down production during anabolic or catabolic reactions. Such reaction products may inhibit the enzymes that catalyzed their production through the mechanisms described above.

The production of both amino acids and nucleotides is controlled through feedback inhibition. Additionally, ATP is an allosteric regulator of some of the enzymes involved in the catabolic breakdown of sugar, the process that creates ATP. In this way, when ATP is in abundant supply, the cell can prevent the production of ATP. On the other hand, ADP serves as a positive allosteric regulator (an allosteric activator) for some of the same enzymes that are inhibited by ATP. Thus, when relative levels of ADP are high compared to ATP, the cell is triggered to produce more ATP through sugar catabolism.

|

Question 5.2

What are different types of energy and which one is most commonly used by animals to sustain and maintain life? |

|

Question 5.3

How would energy production and needs be affected by body size of an animal? What about its environment (aquatic versus terrestrial)? |