3.2 – Circulatory Systems

The content of this chapter was adapted from the Concepts of Biology-1st Canadian Edition open textbook by Charles Molnar and Jane Gair (Chapter 11.3- Circulatory and Respiratory Systems).

|

3.2. Compare and contrast different circulatory systems using specific animal examples and evolution. |

The circulatory system

The circulatory system is a network of vessels—the arteries, veins, and capillaries—and a pump, the heart. In all vertebrate organisms this is a closed-loop system, in which the blood is largely separated from the body’s other extracellular fluid compartment, the interstitial fluid, which is the fluid bathing the cells. Blood circulates inside blood vessels and circulates unidirectionally from the heart around one of two circulatory routes, then returns to the heart again; this is a closed circulatory system. Open circulatory systems are found in invertebrate animals in which the circulatory fluid bathes the internal organs directly even though it may be moved about with a pumping heart.

The heart

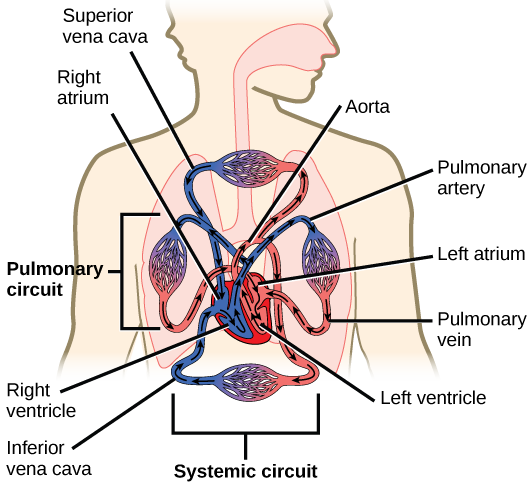

The heart is a complex muscle that consists of two pumps: one that pumps blood through pulmonary circulation to the lungs, and the other that pumps blood through systemic circulation to the rest of the body’s tissues (and the heart itself).

The heart is asymmetrical, with the left side being larger than the right side, correlating with the different sizes of the pulmonary and systemic circuits (Figure 3.7). In humans, the heart is about the size of a clenched fist; it is divided into four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. There is one atrium and one ventricle on the right side and one atrium and one ventricle on the left side. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation through the major veins: the superior vena cava, which drains blood from the head and from the veins that come from the arms, as well as the inferior vena cava, which drains blood from the veins that come from the lower organs and the legs. This deoxygenated blood then passes to the right ventricle through the tricuspid valve, which prevents the backflow of blood. After it is filled, the right ventricle contracts, pumping the blood to the lungs for reoxygenation. The left atrium receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs. This blood passes through the bicuspid valve to the left ventricle where the blood is pumped into the aorta. The aorta is the major artery of the body, taking oxygenated blood to the organs and muscles of the body. This pattern of pumping is referred to as double circulation and is found in all mammals. (Figure 3.7).

|

Question 3.6 Which of the following statements about the circulatory system is false? |

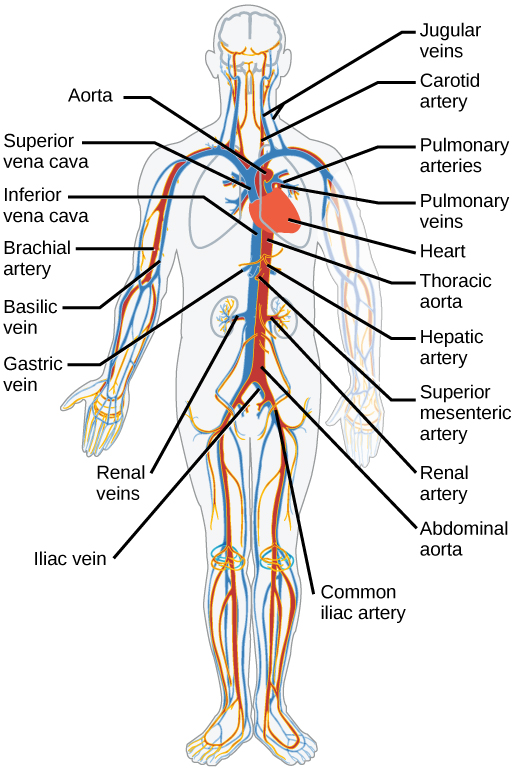

Blood vessels

The blood from the heart is carried through the body by a complex network of blood vessels (Figure 3.8). Arteries take blood away from the heart. The main artery of the systemic circulation is the aorta; it branches into major arteries that take blood to different limbs and organs. The aorta and arteries near the heart have heavy but elastic walls that respond to and smooth out the pressure differences caused by the beating heart. Arteries farther away from the heart have more muscle tissue in their walls that can constrict to affect flow rates of blood. The major arteries diverge into minor arteries, and then smaller vessels called arterioles, to reach more deeply into the muscles and organs of the body.

Arterioles diverge into capillary beds. Capillary beds contain a large number, 10’s to 100’s of capillaries that branch among the cells of the body. Capillaries are narrow-diameter tubes that can fit single red blood cells and are the sites for the exchange of nutrients, waste, and oxygen with tissues at the cellular level. Fluid also leaks from the blood into the interstitial space from the capillaries. The capillaries converge again into venules that connect to minor veins that finally connect to major veins. Veins are blood vessels that bring blood high in carbon dioxide back to the heart. Veins are not as thick-walled as arteries, since pressure is lower, and they have valves along their length that prevent backflow of blood away from the heart. The major veins drain blood from the same organs and limbs that the major arteries supply.

Blood flow refers to the movement of blood through a vessel, tissue, or organ, and is usually expressed in terms of volume of blood per unit of time. It is initiated by the contraction of the ventricles of the heart. Ventricular contraction ejects blood into the major arteries, resulting in flow from regions of higher pressure to regions of lower pressure, as blood encounters smaller arteries and arterioles, then capillaries, then the venules and veins of the venous system. This section discusses a number of critical variables that contribute to blood flow throughout the body. It also discusses the factors that impede or slow blood flow, a phenomenon known as resistance.

Hydrostatic pressure is the force exerted by a fluid due to gravitational pull, usually against the wall of the container in which it is located. One form of hydrostatic pressure is blood pressure, the force exerted by blood upon the walls of the blood vessels or the chambers of the heart. Blood pressure may be measured in capillaries and veins, as well as the vessels of the pulmonary circulation; however, the term blood pressure without any specific descriptors typically refers to systemic arterial blood pressure—that is, the pressure of blood flowing in the arteries of the systemic circulation. In clinical practice, this pressure is measured in mm Hg and is usually obtained using the brachial artery of the arm.

The roles of vessel diameter and total area in blood flow and blood pressure

Recall that we classified arterioles as resistance vessels, because given their small lumen, they dramatically slow the flow of blood from arteries. In fact, arterioles are the site of greatest resistance in the entire vascular network. This may seem surprising, given that capillaries have a smaller size. How can this phenomenon be explained?

Figure 3.9 compares vessel diameter, total cross-sectional area, average blood pressure, and blood velocity through the systemic vessels. Notice in parts (a) and (b) that the total cross-sectional area of the body’s capillary beds is far greater than any other type of vessel. Although the diameter of an individual capillary is significantly smaller than the diameter of an arteriole, there are vastly more capillaries in the body than there are other types of blood vessels. Part (c) shows that blood pressure drops unevenly as blood travels from arteries to arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins, and encounters greater resistance. However, the site of the most precipitous drop, and the site of greatest resistance, is the arterioles. This explains why vasodilation and vasoconstriction of arterioles play more significant roles in regulating blood pressure than do the vasodilation and vasoconstriction of other vessels.

Part (d) shows that the velocity (speed) of blood flow decreases dramatically as the blood moves from arteries to arterioles to capillaries. This slow flow rate allows more time for exchange processes to occur. As blood flows through the veins, the rate of velocity increases, as blood is returned to the heart.

|

Question 3.7

Where would flow be the fastest, narrow or wide tube? Why? |

|

Question 3.8

How is this relevant for blood transport through a vertebrate body? |

|

Question 3.9

How does the giraffe pump blood to its head? |