Jen Johnson

Equity and Working with Families

“The term cultural safety has us ask what we need to understand aboriginal peoples’ sense of danger or risk when they bring themselves to a place for screening, counselling, or therapy. If there is a sense that one’s values, language or ways of life are threatened or looked down upon, then we speak of the environment not being culturally safe.”

Inuit Tuttarvingat, n.d.

Equity

All of us have culture. Factors such as ethnicity, religion, family structure, and history influence our family practices. Child-rearing approaches vary across individuals, families, and cultures. There is an abundance of safe and healthy parenting practices that may differ from your own. Working with children and families of another cultural background involves understanding, respect, and a special effort to appreciate the context of that culture. Acknowledging differences in culture, ethnicity and equity start with learning how to incorporate safety into practice. To be effective when working with families of different backgrounds, one needs to be sensitive, open, and respectful.

Ontario’s child welfare agencies are mandated to protect children and youth who experience neglect or abuse. This began as a response to the ongoing marginalization of poor families and the children and youth who were dealing with social and economic hardships caused by ongoing industrialization and urbanization (“One Vision One Voice,” n.d.). “Like other Canadian institutions, child welfare agencies have evolved within a historical context of white supremacy, colonialism, and anti-Black racism, all of which have been woven into the fabric of child welfare policies and practices, leading to the creation of long-standing disproportionalities and disparities for African Canadian and Indigenous communities” (“One Vision One Voice,” n.d.). As a result of this imbalance, a thorough response is needed to amend the child welfare system (Hasford, 2015).

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) defines child welfare as the provision of social services to children in need (Hall, 2012.). Children or youth should only be placed in the foster care system, as a last resort, after significant attempts to support the family in understanding and meeting the child’s needs. Traditionally, the child welfare system has operated from a Eurocentric cultural standpoint (Hall, 2012). The placement of Black children, Indigenous children, and other children of colour has been contingent on the Eurocentric environmental experience, which does not consider the special needs or experiences of children from non-Eurocentric families (Hall, 2012.).

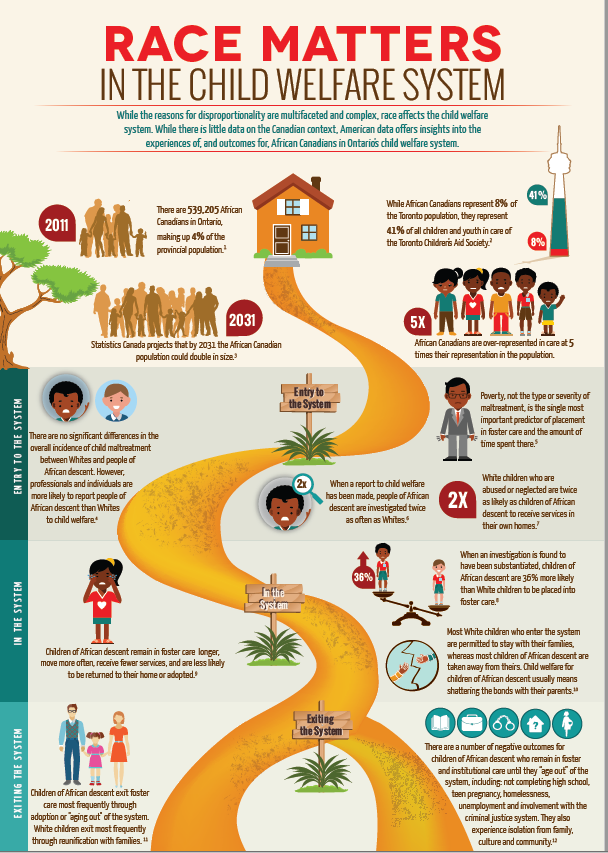

Child Welfare organizations around Ontario have started to acknowledge and address the disparities among different races as well as services and responses. The pictograph below outlines the experiences and concerns that need to be recognized and addressed to ensure equitable service to all Canadian children and families.

Race Matters in the Child Welfare System

Click the image below to read why Race Matters in the Child Welfare System.

Ontario has recognized this problem and developed Ontario’s anti-racism strategic plan (n.d.). The plan acknowledges that Indigenous children learn more at school about how the Europeans settled in Canada than their own history and connection to this land and that Black children are not informed of postsecondary educational opportunities in the same manner as their white counterparts. The plan acknowledges those seeking to be heard, those who highlight the ongoing racism that continues despite measures like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Black Lives Matter, and recognizes that “institutional biases in policies, practices and processes that privilege, or disadvantage people based on race” (n.d.). Plans, including, but not limited to, Ontario’s anti-racism strategic plan, highlight important practices that need to be embraced by individuals, schools, governments, and social services agencies to eradicate racism.

Many racialized groups have concerns about stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Indigenous children and youth are overrepresented in Ontario’s child welfare system. This is due to the historical and ongoing legacy of colonization and anti-Indigenous racism perpetrated against First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in Canada. Black children and youth are also overrepresented due to the historical legacy of slavery and the colonization of people of African descent. Issues that have led to the over-representation of Indigenous and Black children in the child welfare system are elaborate, involved, and multidimensional (Interrupted Childhoods, n.d.). For example, intergenerational effects of colonialism, poverty, slavery, prejudice, and racism are all factors in the child welfare involvement of Indigenous and Black children (“Interrupted Childhoods,” n.d.). There is evidence that Indigenous, Black, and other racialized children are overrepresented in the child welfare system when compared to the general population. In 2015, the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto noted that Black children represented 40.8 percent of children in care, yet Black children comprised only 8.5 percent of Toronto’s population (“Under Suspicion,” n.d.). Research data collected in 2011 from Statistics Canada noted that although Aboriginal children comprise only 3.4 percent of children in Ontario, they represent 25.5 percent of children in foster care (“Under Suspicion,” n.d.).

Other regions in Ontario have also identified concerns; the Black Community Action Network of Peel identified at least eight contributors to racial disproportionality with the Children’s Aid Society. These include anti-black racism, racialized poverty, immigration stress, biased decision-making, agency-system factors, placement dynamics, policy impacts, and lack of culturally relevant services (Hasford, 2015).

It is important for professionals working with children and families to recognize that overrepresentation begins at the referral stage based on racial and ethnic stereotypes. We all need to be aware of personal and systemic biases that may impact our interactions with families. Black families and Indigenous families are still more likely to be reported to a child welfare organization and investigated for abuse, regardless of the changes to societal views and cultural competency training.

Professionals can adapt to support the cultural identity of children and families. It is important to look at cultural safety and why it is important to incorporate this into our care of the children and families that we work with. Much like adopting a strengths-based approach to working with families, working in a culturally appropriate or culturally safe way may require you to take a different stance towards your work and your families.

![]() How do you think one may do this? Reflect on this question.

How do you think one may do this? Reflect on this question.

Cultural safety or responsiveness allows one to respond respectfully and effectively to people of all cultures, languages, classes, races, ethnic backgrounds, disabilities, religions, genders, sexual orientations, and other diversity factors in a manner that recognizes, affirms, and values their worth. Being culturally responsive requires having the ability to understand diversity, recognize potential biases, and look beyond differences to work productively with children, families, and communities whose cultural contexts are different from one’s own.

Ways to be Culturally Responsive or Safe:

- Reflect on your own culture and beliefs. It is difficult to understand another person’s culture if you are not familiar with your own.

- Ensure clear, direct, and respectful communication.

- Develop a positive relationship with your families.

- Avoid stereotypes and assumptions. Be open to learning about the cultural practices and worldviews of others.

- Be willing to engage in a conversation where knowledge is mutually shared.

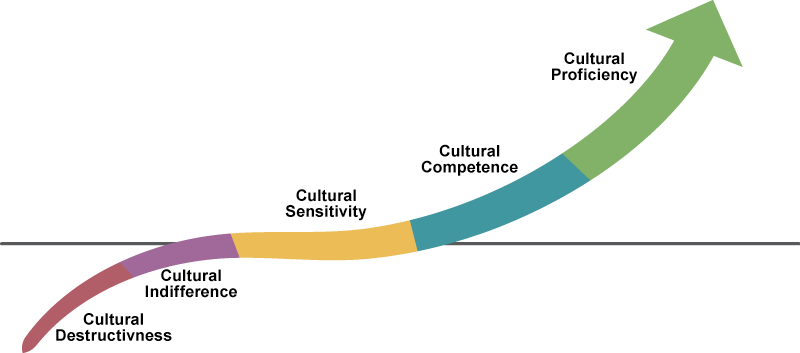

Cultural Competency Continuum

This is an example of a cultural competence continuum model which points out several different stances that an individual may have with understanding and accepting culture. On the far left, cultural destructiveness focuses on forced assimilation, subjugation, rights, and privileges for dominant groups only. Cultural indifference is the attempt to ignore differences and treat everyone the same, while cultural sensitivity acknowledges that differences, as well as similarities, exist. Cultural competence respects and accepts differences but tends to focus on simple stereotypes of rituals and customs and does not account for historical effects and socio-economic status. The goal is to go beyond competence and toward cultural proficiency. This would include implementing changes to improve services based on cultural needs and learning more about diverse groups to provide fully inclusive practices.

Striving for a Community of CULTURAL SAFETY

Irihapeti Ramsden, a Maori nurse and writer, developed the concept of cultural safety from an Indigenous worldview. This concept was focused on working with Maori patients and families in the healthcare setting, and the word ‘safety’ was deliberately chosen to highlight the power differentials inherent in professional settings. Cultural safety switches a professional’s knowledge of culture to how the other person perceives the safety of the situation, this includes the power inherent in your professional position.

As a professional working with families, cultural safety is an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in racialized communities. It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe. Understanding the importance of cultural safety helps educators see the impact of their own social, political, and historical contexts on their practice. Cultural safety involves developing an ongoing personal practice of critical self-reflection, paying attention to how social and historical contexts shape perspectives and being honest about one’s own power and privilege.

Within the child welfare system, there are many identified interventions to address and reduce racial disproportionalities. Resources and supports can have a positive outcome and impact when offered to children and youth who are at risk of child welfare involvement. Programs directed toward culturally-centred activities can help youth understand the systematic oppression they may experience, which can lead to positive outcomes (Hasford, 2015).

Cultural safety means an environment is spiritually, socially, emotionally as well as physically safe for people. It changes your relationship with the family, it becomes a two-way relationship, as people are much more likely to engage with you if they feel safe.

There are many ways to address systemic racism, and it is everyone’s responsibility to learn strategies to identify, respond, and prevent further harm. Strategies that could be utilized include ongoing training or workplace development, as well as ensuring all members of the community are held accountable for their actions. Governments and social service agencies need to advocate for effective leadership and ongoing communication strategies (Under Suspicion, n.d.).

This change in perspective is a shift from learning about a group to learning about a person. It is about listening to and supporting children and families from different races, cultures, ages, genders, sexual orientations, and economic or educational statuses. Cultural competence is essential; our opportunity to build relationships is impossible without it. Instead, we co-exist with people we don’t understand, creating a higher risk of misunderstanding, hurt feelings, and bias, all of which could be avoided.