1 Challenges and Opportunities of Distance/Online Instruction

Confronting the Challenges of the Distance/Online Instructional Modality

Benoît Raucent; Jon Dron; Aliaa Dakroury; Lynne N. Kennette; and Diane Riddell

What is the essence and meaning of distance and online learning? This is one of the questions that was examined during the first symposium event, focusing on exchanges and discussions related to transforming attitudes toward distance/online modalities and transforming perspectives regarding the teaching and learning paradigm. Keynote speakers, Dr. Benoît Raucent and Dr. Jon Dron, as well as other participants, shared the challenges they have faced with this pedagogical transition and provided insights into their own experiences with online modes of teaching and learning. They also offered pedagogical approaches and suggestions that best facilitates distance/online instruction and learning.

Pre-Symposium Survey: Main Themes

Several themes emerged from a pre-symposium survey that participants were asked to complete to gauge any progressive changes within and across events. Along with the discussions that occurred during the symposium, this survey informed our understanding of participants’ lived experience related to online teaching and learning. The survey inquired about the online teaching experience and concerns regarding students’ online learning experiences. The main themes characterizing the online teaching experience include 1) social isolation experienced by professors and students (i.e., feeling disconnected and awkward, a lack of engagement from students, and alienation from colleagues and peers); 2) positive professional development opportunities (i.e., exploring new approaches and engaging in pedagogical reflection that was challenging but rewarding; 3) the emotional toll of online learning (i.e., feeling fatigued, stressed, frustrated, exhausted, and anxious); 4) a dynamic and diverse space of possibilities (i.e., online teaching required creativity, flexibility, innovation, experimentation and adaptation, but it was transformative and exciting); and 5) an overwhelming increase in workload (i.e., online teaching was viewed as time-consuming, demanding, intense, and endless). Symposium participants reported the following concerns regarding students’ online learning experience: 1) Improving the online/distanced learning experience for students; 2) Ensuring equity and accessibility; and 3) Gauging the limits of online/distanced learning (i.e., how to know what students are actually learning and the possibilities of online modalities). It is our intention that these themes, along with key themes that are highlighted in certain sections of this contribution, will inform pedagogy and decision-making for anyone involved in online and distance education.

Session 1

The first session of the three-part series of virtual events featured the following: welcoming remarks, an overview of student feedback about the university’s transition to distance and online learning and ways to meet their needs, the purpose and goals of the symposium which highlighted the keynote speakers and individual sessions of the future events and an opportunity to reflect on and discuss dilemmas and challenges experienced during the transition to online instruction in small groups using a series of guiding questions. To reinforce the reflective process, each group was asked to document their reflections and discussion as a group in a Google Forms document. A summary of the results outlined common challenges experienced by the participants, and what they reported as the most helpful strategies and resources they used to overcome those challenges. Interestingly, the themes that emerged in the pre-symposium survey were not only supported during the breakout discussions during this session, but also during the panelist discussions and the keynote speaker sessions. Six main themes emerged during the discussion groups: 1) the negative social and emotional consequences to student well-being; 2) the need for flexibility (i.e., with Zoom meetings, office hours, deadlines, and assignments); 3) managing an increased workload (for students and professors); 4) ways to monitor and increase student engagement and class interactions; 5) re-thinking approaches to how and what type of feedback is provided to students; and 6) logistic difficulties and concerns (i.e., technical difficulties and barriers, limitations within Zoom or other apps, and finding resources/ tools).

Session 2: Keynote Speaker Dr. Benoît Raucent

During this session, the series’ first keynote speaker, Dr. Benoît Raucent, delivered a presentation titled the Key Questions and Reflections for Approaching Distance Instruction.

Dr. Raucent’s presentation discussed issues that emerge when initiating distance education activities, such as having students who are not very motivated, are stressed and are dealing with equipment issues. He raised the key question of “Why move toward a distance modality?” He postulated that one possible reason may be to leverage distance learning as an opportunity to respond to current needs and to make it a common way to access training. Dr. Raucent’s presentation provided great insights into issues that emerge when initiating distance education activities and also fostered reflection geared toward changing established distance education practices. He provided suggestions for improving the pedagogical online presence, which anyone involved in distance education, including instructors, teachers, tutors, advisors, instructional designers, and administrators would benefit from. Dr. Raucent expressed his sentiment that it is not a matter of not having sufficient tools and trying to develop new tools, but rather ensuring that available tools are used correctly. Key themes and takeaways from Dr. Raucent’s session include being mindful of missed or hidden opportunities, fostering a learning community amongst colleagues and students, promoting student engagement, and creating a pedagogical presence online.

About Dr. Benoît Raucent

Session 3

Session 3 involved discussions surrounding a survey result on instructional issues that emerged for instructors, students, and teaching assistants during their transition to an online modality. Using the facilitation of prompt questions in a Google Document file in small groups, participants unpacked and addressed these issues. In an effort to encourage solution-oriented collaborative brainstorming, participants were invited to select from one of the following eight discussion topics: Active learning in online learning environments; Designing and Implementing Meaningful Evaluations; Presenting Cheating and Plagiarism; Designing and Facilitating Group Work in a Virtual Context; Teaching Large Enrolment Online Courses; Community-building in online environments; Ethics, Responsibilities and Netiquette; Supporting Student Wellness.

Session 4

The fourth session, Challenges and Opportunities, involved the sharing of lived experiences of three instructors from varied faculties and disciplines regarding their transition to online learning. This included the most significant challenges they encountered and the strategies they used to leverage the opportunities offered by this modality. Discussion themes that emerged from the panelist discussions focused on academic integrity, student and professor well-being, building a community with students, course design, and the importance of collaboration with students and colleagues.

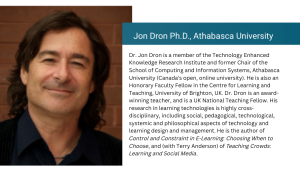

Session 5: Keynote Speaker Dr. Jon Dron

The second keynote speaker, Dr. Jon Dron, presented on How Distance Changes Everything.

Dr. Dron discussed the evolution of in-person educational systems, including the use of counter-technologies, which are pedagogical methods used as solutions to overcome issues created by in-person teaching, like physical constraints. The invention of physical boundaries (i.e., boundaries in space and time) and scarce resources were created to overcome these issues. These included the invention of rules and regulations, lectures, exams, grades, teachers being in control, and more. He refers to these as “controlling” pedagogical patterns that are the easiest path for in-person teaching, which include telling and directing students, having a fixed curriculum, rewarding and punishing students, having fixed outcomes, and more. These inventions led to the present educational systems. However, when used in distance teaching, these technologies can have adverse effects on learner autonomy, competence and other factors such as social relatedness. Dr. Dron discussed that one needs to feel autonomy, in control of what one is doing, and support for competence, which students lack by default. Thus, giving students control, supporting personal goals, interests, and encouraging the use of existing skills can help support them to mitigate the adverse effects listed above. Dr. Dron’s presentation revealed some of the central Faustian Bargains of in-person and online learning and he suggested practical approaches to thinking about how and when to use these deliveries. He explored the art of relinquishing direct control over student learning to giving them freedom to choose (e.g., alternatives to textbooks, exams, etc.) effectively. Themes that emerged from Dr. Dron’s session focused on “un-teaching”, de-coupling assessment and learning, balancing innovation with students’ expectations, and personalizing education to meet students’ educational needs.

About Dr. Jon Dron

For more information, see http://teachingcrowds.ca

Session 6

This final session, Bringing it All Together and Looking Ahead involved a summary of the presented ideas, practices, and themes and presented a sample toolkit of resources for educators to consider in their journey in online and distance modalities. Specifically, these help educators to plan, prepare, facilitate learning. Other resources included websites from various academic institutions with information, suggestions, tools, webinars, and modules to assist with continued online and distance teaching and learning experiences. A Participant Lounge to continue engaging in discussions, share with others and to provide feedback for future symposium events was made available for participants and they were informed about the present publication.

Participants’ Reflections

Online/Distance Learning: Defying the Stereotype

Aliaa Dakroury

Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Ontario

I have been teaching online in higher education since 2011, and it is quite disappointing to state that the persistent stigma surrounding distance/online teaching remains one of my biggest challenges. In other words, it is not an instructor/professor perspective that implies such a view, rather, the recipients (i.e., students), peers (i.e., fellow colleagues), and community at-large. Misconceptions that online/distance teaching simply implies a “laid-back” teaching style, that focuses simply on: posting recorded videos; easy-graded assignments; enabling cheating and other academic integrity infringement with no serious consequences; among other stereotypical assumptions on the distance/online modality – all of which remain the real challenge for me throughout the years.

One of the positive outcomes of the pandemic (surprisingly) and with the urgency needed for all professors to switch from in-person to online teaching, one can argue that such an assumption continued to be present among students. Yet, from colleagues’ perspective, maybe it was the actual realization — for the first time — that distance/online modality is not that “laid-back” of a teaching mode for sure, and indeed involved an extreme amount of time, labour, creativity, and challenging oneself to think out of the box, and possess a real empathy for students’ position.

From the students’ perspective, especially for those who did not take any online/distance classes, establishing an individual and independent studying habit; possessing an accessible textbook; keeping an interaction with peers, and communication with the professor were among the main challenges one has observed in the recent years.

For me, the course design and planning are key to deliver a content that engages students, meets the course objectives, and equally relief students’ anxiety attending to their changing needs. I keep the content of the course extremely appealing aesthetically, easy to navigate, and establish a weekly routine throughout the course. Each week has a sperate module clearly labelled with the theme corresponding to the course outline. When students access the weekly module, they will find the consistent sub-modules: 1) lecture notes – written, audio, or video; 2) an accessible version of the textbook or a link to the corresponding assigned reading in the library resources (that is hyperlinked and tested to avoid any broken links); 3) assessment (if any) that is clearly labelled with the grade weight, marking rubric, submission tool; 4) discussion forum (blog, discussion, chat, wiki, ..etc.); and finally 5) a Q & A forum where students can pose any question about anything (and it is extremely important to check it very frequently to attend to any requests or needs).

One of the successful strategies I used throughout the years, although I teach online classes asynchronously, I set at least one date at the beginning of the course to “meet and greet” students using the Zoom or Teams tool. We introduce ourselves, get to know each other, and share the screen to tour the course online and answer any of their questions. I would do the same before any big assignment, or exam to make sure that students are on track for any assessment. I also set the Brightspace “intelligent agent” to tell me if a student did not log on for 48 hours, so that I can send them a note checking on them to make sure that they are not lost in the cyber-world. The class progress tool in the LMS is excellent to see what the tools are that students tend to use (or like) more, to continue using it versus others that were not so useful for them. Providing feedback to each (and every) assignment before (and be creative in giving them resources to improve) was an efficient strategy as well.

In short, I do believe that if any professor would think of themselves as a student in-need of mentorship and guidance, not only to the subject matter in their disciplines of study, but equally to the use of new tools that they have not used prior to taking the class, they will ensure to fill in the gaps in the course and content online.

Online Instruction: Challenges and Opportunities

Lynne N. Kennette

Durham College, Oshawa, Ontario

Online education brings with it unique challenges from those experienced in a classroom. I had become quite familiar with these challenges pre-pandemic since I have always taught classes primarily online. However, the students and their challenges changed during the pandemic because the students that I was teaching were forced to take this course online. Prior, I had been teaching students who chose to take an online class, so they had wanted this delivery. But now, not only were they being forced to learn online, the majority of their classes (if not all of them) were fully online. The two primary challenges I needed to address were (1) the additional need for flexibility; and (2) the opportunities to form social connections (with me and with their peers).

Flexibility

First, I recognized that, in addition to potential COVID-related health challenges (caring for a loved one, needing to isolate, becoming ill, etc.), students would likely also experience additional burdens requiring flexibility such as assisting children (their own or younger siblings) with their homework, or even helping a parent navigate some sort of technology for work. To accommodate this additional need for flexibility, I delivered all of my content asynchronously, with weekly deadlines for learning activities (e.g., experiments). This content was also chunked into small units so that students could easily complete the weekly content in 15–30-minute chunks. The delivery of my course content varied so that it included videos explaining a concept, text, figures, and experiments. For each week’s content (an accompanying tasks), students had 10 days during which to complete it: from the Thursday before the week until the end of the week (Sunday). I graded everything on a rolling basis so that students could proceed at their own pace. I was teaching my online courses this way pre-pandemic, but I recognized that it provided students with additional benefits (and, having 2 small children of my own (aged 1 and 6)), I could better appreciate the value that this flexibility afforded to my students).

Social Connections

But what about social connections? Because all classes were online, the need for social connections was even more important. If the course is delivered fully asynchronously, how do we form connections? First, it is important to point out that, although students could complete the course without talking to me, there was an optional live meeting every week (like office hours) where anyone could pop in and talk to me about the course content (or anything else, really).

In addition to these weekly, synchronous, drop-in times, I assigned an introduction activity during the first week of class. These multimedia introductions could include a photo or video (either of themselves or an animated character using a free website like Voki). I also encouraged them to include, as part of their introduction, one thing that we would not know about them from looking at them (e.g., I have 8 siblings; I was born in the Netherlands; I really like to play Minecraft; etc.) This resulted in students being interested in each other and their interests, finding commonalities, and ultimately, finding partners/groups for their assignments based on these introductions (and subsequent responses).

Yes, my course assignments needed to be completed in groups of at least 2 students. Although this may seem like an additional challenge online, I provided students with tools (e.g., Google Docs) and an explanation of the value or practicing these skills for their future employment. Additionally, each student (individually) completed a group work reflection where they indicated how well their group worked, who completed which section(s) of the assignment/how the work was divided, what worked well in their group, what they would do differently next time, and scored their assignment using the rubric. This gave me a way to see how things went (especially after the first assignment), and students were able to learn from their experience and apply these skills to subsequent group assignments.

Finally, students had weekly opportunities to discuss their experiment results and other topics in discussion board and Padlets, which provided a way for students to share content that was relevant to the course but also personal (e.g., for the chapter on learning, students were tasked with finding an example of observational learning and posting a picture of it on a Padlet – I posted a picture of my daughter putting her shoes on after watching her big brother put his on). This reinforced the concept (both from thinking about it more deeply, and also seeing everyone’s examples) and allowed students to connect to each other in a different way.

Conclusion

Students sent many emails voicing their appreciation for the added flexibility in my course compared to some or their other courses and experiencing these challenges with my students has improved my social presence online. I encourage other instructors to consider asynchronous delivery and how they can increase social connections online.

Maintaining Connections Online

Lynne N. Kennette

Durham College, Oshawa, Ontario

Large online classes are uniquely challenging as they can make students feel isolated. They are also challenging for faculty to ensure personalized connections with a large number of students. Having taught primarily online courses for the last decade, I was able to help some of my colleagues implement ways to personalize their students’ experiences and develop meaningful connections with students. Below, I share a few of the ways I have reduced student isolation and increased connections among students and also with myself as the instructor.

First, whether teaching a course synchronously or asynchronously, an opportunity for synchronous virtual office hours is important. Students can stop in and chat about course content or other things that may be important to them (e.g., gaining research experience, applying to another school/program, your experience in your field, etc.). Scheduling this time shows students that you care and are available to them (even if they do not attend) and this increases their perception of your psychological warmth, making them feel like there is at least a potential for a social connection there.

Next, students need to find a way to introduce themselves to and interact with others in the class. A discussion board or Padlet works well in smaller classes, but with a larger number of students, dividing students into smaller groups makes the interactions more intimate and allows for deeper connections. When asking students to introduce themselves, I also ask that they include a photo or video (even if it is of an animated Voki instead of themselves), and a fun fact about themselves (e.g., coming from a large family, speaking an additional language, having some skill or talent, introducing their pets, etc). In this way, students go beyond the name-major-year introduction, and are able to identify commonalities or even future friends.

My secondary purpose to these introductions is to facilitate students finding a partner or group for their class assignments. With all classes being online, students don’t have the option to ask the person they sit next to in class, or someone they recognize from another class to be their partner. In this way, these introductionsre able to facilitate connections and offer an “in” for students to begin a discussion and ultimately form a partnership.

Finally, I have saved my best tip for last! I use personalized intelligent agents through the learning management system (we use Brightspace/D2L, but there are similar tools in most learning management systems). The intelligent agents allow instructors to set up rules which automatically push out email to students meeting the established criteria with a personalized message. Here are some examples of the agents I have set up in my course:

- Welcome to the class email (“Dear X, I noticed you just logged into the course for the first time, so welcome!…).

- Remind students when they have not logged in for 9 consecutive days.

- Congratulatory message when they earn 80% or higher on a test or assignment.

- Study tips for students earning 60% or below on a test or assignment.

- Email confirming that I have received their assignment file

- Keep up the good work email when a student completes a weekly checklist (which outlines their tasks for the week).

These agents have proved invaluable in larger classes, because it allows students to feel connected to the instructor. Further, students often reply to these emails with a thank you (for the study tips or congratulatory message) or to reach out for additional help (I will come to your office hours next week) or explanation (I had a rough week, but I will do better on the next assignment).

Conclusion

Virtual office hours, small group introductions, group projects, and especially, intelligent agents, are great ways to reduce students’ feelings of isolations in larger classes. These are particularly useful in online classes, but can also be used to support social relationships in a face-to-face classroom.

Connecting in the Online Environment

Diane Riddell

University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario

My third year Public Relations class usually includes between 70 and 80 students. While most come from my department (Communication), it is a course with no pre-requisites, so many students also come from other faculties. This year, students joined class online from various countries and time zones as well.

I structured this three-hour course in two parts – a one and a half-hour live meeting each week that was also recorded, as well as an online pre-recorded module for students that covered readings, a mini-lecture and other activities that students would complete separately.

Here are some of the strategies myself and my Teaching Assistant, Michelle Hennessey, used to foster student connections with us, with their peers and the course content.

Student Connections with the Teaching Team

We used the University of Ottawa D2L tool, Brightspace, as the primary means of written communication with students in order to push announcements, updates and other information to the class.

For the live class, I opened the Zoom call 20 minutes early and spent that time welcoming students by first name as they arrived online, chatting informally and making small talk. This was intended to provide a similar experience to students arriving in a classroom before class starts. Because students knew I would be there, some chose to come early to chat. I did the same at the end of the formal class time, staying 20 to 30 minutes after class to talk to students and answer any questions they may have. There were always students who stayed. Sometimes just one or two, sometimes more.

The Teaching Assistant and I also made a point of reaching out to students on a regular basis – if we noticed they had not handed in assignments or were otherwise getting behind. We did this via e-mail and worked hard to encourage students towards success. There were some students who were ready to give up, but we walked alongside them and provided encouragement and flexibility. In the end, everyone who responded to our requests to work together towards success passed the course.

Student Connections with Peers

The course included group-work with each team of six to eight students completing two templated assignments connected to their group work prior to a group presentation at the end of the semester. I had slightly adjusted the requirements for the online experience compared to the previous year by reducing the number of group assignments before the presentation from three to two. Students selected a crisis of their choice to follow throughout the semester. I allowed for time in class for groups to work together and used the Zoom meeting room function for students to move from the broad class to their groups. I travelled to the breakout rooms to converse with teams. I found that while most students would not open their video in class, they would do so in the breakout rooms because these were not recorded. I also found that in such a setting, they were not uncomfortable leaving their cameras on while I visited, and it was wonderful for me to see many of the students.

Student Connections with Course Content

Students accessed course content for the week and previous weeks online. I posted that week’s pre-recorded module before the live class. Students seemed to enjoy the flexibility this gave them to watch anytime, although about three quarters of the class attended the live meeting anyway – sometimes more than I would get for in-person classes!

I chose not to take attendance. Instead, I replaced the usual attendance points with Participation Prompters. These were opportunities to earn points to a maximum of 10 for the semester, by watching a video, commenting on a reading, responding to a post, helping facilitate the class or another activity. The idea was to provide options and help students engage with the material and with their colleagues and do some critical thinking. Interestingly, I found that students are seemingly not accustomed to such flexibility. At the end of the semester when we first tallied the points, the Teacher Assistant and I spent quite a bit of time reminding students to not leave their participation points on the table. As I reflected upon this, the thought occurred to me that while students may enjoy innovative and varied approaches, it may be harder for them to understand these initially when they are accustomed to getting marks for attendance, so reinforcement and repeated messaging of new ways of working is likely required.

About the Authors

Dr. Aliaa Dakroury

Dr. Aliaa Dakroury is an Associate Professor and the former director of the School of Social communication at Saint Paul University, Ottawa.She holds a BA in Media studies with specialization in public relations from Cairo University, and both a MA and PhD from Carleton University’s School of Journalism and communication. Her research interest focuses on the historiography and the application of the right to communicate and the analysis of media policies in and outside Canada. She can be reached at adakrour@uottawa.ca.

Dr. Lynne N. Kennette

After completing her double Bachelor’s honours degree at the University of Windsor (Windsor, Ontario) in French and Psychology, Dr. Lynne N. Kennette earned a Master’s and Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology from Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan). She is currently a professor of psychology in the Faculty of Liberal Studies at Durham College (Oshawa, Ontario), where she primarily teaches introductory psychology elective courses. Her interests include mentorship, the scholarship of teaching and learning, and optimal student performance in the classroom.

Diane Riddell

Diane Riddell is a PhD candidate in the Department of Communication at University of Ottawa. She holds a Bachelor of Applied Arts in Journalism from Toronto Metropolitan University and a Master of Science in Communications Management from Syracuse University. Diane has also worked as a part-time public relations professor at University of Ottawa. Prior to starting PhD studies, Diane spent many years as a communications and public relations executive and manager in both the private and public sectors. Her research focuses on the experience of technostress of public relations practitioners. She can be reached at dridd024@uottawa.ca.