2 Transforming Perspectives Regarding the Teaching and Learning Paradigm

Taking Stock of the Changes in Thinking about, and Practice of, Distance/Online Instruction and Learning

Martine Pellerin; Sean Michael Morris; Michael K. Barbour; and Diane Riddell

To continue discussions from the first symposium, the second event focused on deepening the discussions around transforming attitudes toward distance and online modalities and transforming perspectives regarding the teaching and learning paradigm. Drs. Martine Pellerin and Sean Michael Morris presented their work on motivation and attitudinal shifts in innovative and digital pedagogies.

Pre-Symposium Survey: Main Themes

Participants completed a pre-symposium survey inquiring about the online teaching learning experiences, as they did with the first symposium. The few emergent themes from this event were similar to the first event but with greater depth. The following themes summarizes the three words participants shared to capture the online teaching experience: 1) the overwhelming and stressful nature of online/distance teaching; 2) positive professional development opportunities; and 3) social isolation. Whereas participants’ responses indicated that professional development opportunities and the dynamic and diverse possibilities of online teaching were viewed as two separate ideas in the first event, they reported viewing those dynamic and diverse possibilities as more directly related to professional development and increased competence. The negative emotional effects of online/distance learning and its overwhelming nature remained significant experiences of the teaching experiences as well as isolation and disconnect. More specially, instructors’ own feelings of isolation took on a greater focus on this second survey. Secondly, the participants shared their concerns regarding the online learning experience of the students. One theme re-emerged from the first event: improving the online/distance learning experience for students. The second and third themes, improving student engagement and motivation and supporting students’ mental health shifted towards connections, community, reducing social isolation, and mental health concerns. Significantly, these three themes emerged during each session of the second Symposium series. For example, themes from the Breakout discussions included: 1) pedagogical flexibility (to meet students’ academic and social needs, and to improve student engagement); 2) the importance of collaboration (for both students and professors); and 3) addressing and supporting mental health concerns.

Session 1

The first session of this transformation area involved welcoming remarks, an overview of the day’s theme and an activity involving participants using guiding questions to discuss the nature of instructors’ and students’ attitudinal shifts in online instruction and learning in small groups.

Session 2: Keynote Speaker Dr. Martine Pellerin

The first keynote speaker of the second symposium series, Dr. Martine Pellerin, presented on the Distance/ Online Teaching and Learning in the Age of COVID-19: A Paradigm Shift to Transform Perspectives on Teaching and Learning.

Dr. Pellerin’s presentation delved into the rapid transformations in pedagogical practices that emerged as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, with the emergence of a new pedagogical practices paradigm being at the heart of the transformation. Dr. Pellerin highlighted how the teachers’ or instructors’ historical role as experts is transforming into that of a coach as well as the students’ role as passive receivers is also transforming into that of an active actor in the learning process. She shared that students need support, they need problem solving skills, ability to work collaboratively, to communicate, and to be creative, but it is also important to acknowledge that they will only be committed if projects reach them on an affective and emotional level and feels authentic to them. Consequently, the aim of emerging pedagogical practices is to engage students through the co-construction of knowledge, the co-creation of content, inquiry-based learning and the development of solutions as global citizens to the global challenges and issues collectively faced. Additionally, new technologies are also contributing to this shift in paradigm by way of encouraging new forms of presentation and expression of knowledge. Key discussion themes from Dr. Pellerin’s presentation focused on the development of autonomy, well-being, increasing student engagement, and creating a pedagogy of care.

About Dr. Martine Pellerin

Session 3

Similar to the Session 3 of the first symposium, participants were invited to select from one of four concurrent presentations focusing on resources and available services. The presentations addressed the following four discussion topics: Online Transition of Student Academic Services, Influencing the Indigenization of the Curriculum at the Faculty Level, Student Mental Health and Wellness Services, and Rethinking the Netiquette.

Session 4: Keynote Speaker Sean Michael Morris

The second keynote speaker, Sean Michael Morris, delivered a presentation titled Teaching through the Screen: Critical Digital Pedagogy after COVID-19.

Sean Michael Morris discussed the lack of reliable best practices as a result of the quick shift to distance/online mode of instruction and learning. Instructors and students alike needed to improvise as the natural synergy of being together in a classroom was abruptly removed. They found themselves dealing with a multitude of dilemmas that the pandemic had created. They did not understand how to teach or work online. Being in a crisis created such a profound lack of literacy in digital pedagogies which affected both the curriculum and the entire community of the classroom. He highlighted the importance of remembering that learners are humans in the physical world, humans do not exist in digital space, that the screen is not a venue but a tool. Thus, teaching is not to be done to a screen but through the screen, to real human beings. In his presentation, he suggested the consideration of developing a critical digital pedagogy that integrates digital literacies with equitable practices to create meaningful learning on both the instructors’ and the students’ sides of the screen in order to affect this transformation. He also highlighted that lasting change comes from “small, intentional, critical steps.” Key themes and additional takeaways from Sean Michael Morris’ presentation include “teaching through the screen” and, in agreement with Dr. Pellerin, creating a pedagogy of care with human beings at the core of learning. Finally, the importance of communication and listening to students, flexibility in varying educational contexts, addressing mental health concerns, and shifting away from traditional teaching methods emerged as themes during the two students and instructors’ panels on their lived experience.

About Sean Michael Morris

Session 5

The fifth session of the second Virtual Symposium series involved the sharing of lived experiences about shifts in attitudes, perceptions and practices related to online learning and instruction. Two students and two professors from varied faculties shared their experiences.

Session 6

Lastly, the series concluded with Concluding Remarks and Looking Ahead which tied all ideas, practices, and themes together from the event. Symposium participants participated in action research groups, and it was highlighted as a way to dig deeper into the day’s discussions and further investigate them. This includes sharing resources, collecting and analyzing data, and reflecting on practice and research via a collective chapter or article.

Participants’ Reflections

Overcoming the Stigma Before Taking Stock

Michael K. Barbour

College of Education and Health Sciences, Touro University California, California

While online learning in Canadian universities had grown annually by approximately 10% per year prior to the pandemic (Johnson, 2020), the rapid transition to and continued use of distance/online modalities over the past 18 months have placed considerable burden upon both instructors and students (Johnson, 2021). Many universities, often through their centres of teaching and learning, put forward a variety of efforts to address these new demands on faculty. As such, the idea that it is important “to take stock and make sense of dilemma-ridden experiences… toward a clearer state of order and understanding of how to effectively design and facilitate learning in distance and online modalities” (Advancement of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2021, p. 1), is a logic and necessary step towards preparing for the emerging new normal. However, before higher education can begin this process of reflection on what has happen, how higher education responded, and what we can and should be doing going forward; we must first wrestle with the realities of the nature and type of distance/online modalities that instructors and students have actually experienced thus far.

In this instance it is important to underscore the distinction between distance/online learning and remote learning.

Online learning, which was based on purposeful instructional planning, using a systematic model of administrative procedures and course development. Online learning also requires the careful consideration of various pedagogical strategies and determination of which are best suited to the specific affordances and challenges of local delivery mediums as well as the purposeful selection of tools based on the strengths and limitations of each one. Finally, careful planning for online learning also requires that teachers be appropriately trained to use the tools available and apply them effectively to facilitate student learning. (Barbour, 2021, para. 15)

This description is contrasted with remote learning as:

a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances. It involves the use of fully remote teaching solutions for instruction or education that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face or as blended or hybrid courses and that will return to that format once the crisis or emergency has abated. The primary objective in these circumstances is not to re-create a robust educational ecosystem but rather to provide temporary access to instruction and instructional supports in a manner that is quick to set up and is reliably available during an emergency or crisis. (Hodges et al., 2020, para. 13)

While this distinction has been made regularly and frequently within academic circles, far too often the differences between these two instructional delivery models have been lost on the media and the general public.

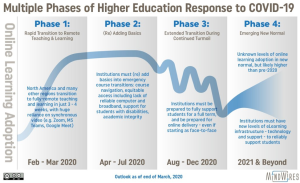

An examination of the actual reality of the higher education response to the pandemic was illustrated well by Hill (2020).

Figure 1. Phases of response to COVID-19 in terms of remote and distance/online learning.

During the spring 2020 semester, faculty and students made a rapid transition to using distance/online tools and pedagogies to provide any modicum of continuity of learning (i.e., Phase 1). As both faculty and students became more comfortable with the tools and the medium, there was a transition from emergency remote learning to remote learning (i.e., Phase 2). While Hill was optimistic in his timeline for Phase 3, the 2020-21 academic year saw universities toggle “between states of lockdown [i.e., remote learning] and openness [i.e., in person learning], depending on their sense of epidemiological data and practical feasibility” (Alexander, 2020, para. 32). Finally, we wonder as the 2021-22 academic year begins whether this will be the first year of the “new normal” in higher education (i.e., Phase 4), or if we are in for yet another year of toggle terms.

Regardless, the difficulties faced by higher education during the remote learning in the first three phases has tarnished the full potential of distance/online learning in phase four. Before we begin to consider questions such as the challenges faced by instructors and students that could not be reconciled, how to ensure student engagement and a sense of community, or the ways to implement meaningful evaluations; we must first acknowledge the realities that faculty and students faced during the unplanned and rapid transition to remote learning. Before we begin to take stock of perceptions towards distance/online learning, how to ensure a wide range of student interactions or consequential feedback and assessments, or the ways to facilitate effective group work; we must first address the conflation of distance/online learning with remote learning. Before we begin to examine the emerging opportunities, the changes in instructional practices or student attitudes, or the future of teaching and learning in higher education; we must first address the stigma associated with distance/online learning.

The Choice to Trust

Diane Riddell

University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario

I made several changes as I developed assessments and feedback for the online course I taught. I would say that the biggest change I made is that I chose to trust in my students during assessments. The last time I taught the course, the mid-term was written in-class. Everyone wrote it at the same time under supervision and with the same questions, in the same order, using a computerized scoring sheet to note answers.

I suppose I could have simply transposed the idea to the online environment by expecting everyone to write the mid-term at the same time online. But the truth is, I did not think that was fair to the students, who were located in various countries and time zones. I wanted to design a process that would allow them to be successful. And I recognized that with COVID, there was already a certain measure of baseline stress in everyone’s lives.

So instead, I made the following bold, and some people might think, crazy change: I opened the mid-term exam for a 24-hour period and allowed each student to write the 90-minute exam whenever they wanted within that time period, so that they could prioritize their commitments and better organize their time. I spent time explaining to the students how that would work, and we posted announcements to strengthen our points and repeat them so there would be clarity.

I am sure there are some who might think that was an insane choice that would invite cheating and other forms of “collaboration”. Yes, cheating was a possibility. But when I think of what happened, I believe the approach made better use of everyone’s time and actually was able to improve upon what we have had in the past, as follows:

#1 – All exams were done within the same 24-hour period. There was less administration time required. Students with accommodations were accommodated within the online system – in the learning platform we were able to program extra time for students who needed it and let them know in advance so they would not worry. There were no additional sessions of the mid-term that were required. And if anyone missed it for a legitimate reason, we could just program the system for another day so that they could write their exam.

#2 – Students could write the exam at a time that worked for them within the 24-hour period. Mid-terms and exam times are stressful for students. The fact that this gave them a measure of control over their schedule likely made things a little less stressful for them – and interestingly what I found is that most students did not wait until the last possible moment to write the exam.

#3 – The online platform drew from a bank of questions and randomized them, which means each exam was different. This likely mitigated the amount of cheating or collaboration that might otherwise arise in a classroom with a written exam where all the questions are presented in the same order.

#4 – My Teacher Assistant, Michelle Hennessey, and I did not observe situations that would have suggested cheating. The marks were well distributed, and we had no concerns. Is it possible some students collaborated? I suppose. I sought to mitigate this by asking students not to, and by reminding them that if they do, it is not a good thing for anyone if I have to report it. I also decided as a prof not to be concerned about it as much, and that helped me with my stress level too.

Another thing I did was reduce the number of group assessments for the class. In the past, I scheduled three group assignments prior to the group’s final presentation. In order to reduce the load on students in the online environment, I reduced the number of group assignments from three to two. I did not cram the third assignment into the two others. I reduced the load, intentionally.

It did not affect the quality of the work, nor the learning students got out of the exercise. It seemed like a more reasonable approach in these times, where there may be fewer opportunities for groups to coalesce and work together. While one or two groups did not work together as effectively as hoped, overall, this was a success and I would do it again, whether the class was online or in-person.

About the Authors

Dr. Michael K. Barbour

Dr. Michael K. Barbour is a Professor of Instructional Design and Director of Faculty Development for the College of Education and Health Sciences at Touro University California. He has been involved with K-12 distance, online, and blended learning for over two decades as a researcher, evaluator, teacher, course designer, and administrator. Michael’s research focuses on the effective design, delivery, and support of K-12 distance, online, and blended learning; including how regulation, governance, and policy can impact effective learning environments. His background and expertise has resulted in invitations to testify before legislative committees and consult with departments of education around the world.

Diane Riddell

Diane Riddell is a PhD candidate in the Department of Communication at University of Ottawa. She holds a Bachelor of Applied Arts in Journalism from Toronto Metropolitan University and a Master of Science in Communications Management from Syracuse University. Diane has also worked as a part-time public relations professor at University of Ottawa. Prior to starting PhD studies, Diane spent many years as a communications and public relations executive and manager in both the private and public sectors. Her research focuses on the experience of technostress of public relations practitioners. She can be reached at dridd024@uottawa.ca.