7 The Shingwauk Family

Chief Shingwaukonse (1773-1854)

Chief Shingwaukonse rose to prominence following the War of 1812, siding with Canada against

the United States. A strong leader and devout Midewiwin, Chief Shingwauk’s vision for his people surrounded education. Chief Shingwauk’s vision of Teaching Wigwams was for the creation of a lodge or schoolhouse where his people and the settlers could learn together.

In 1832, the Chief snowshoed from Garden River to York, Toronto to petition Governor John Colbourne to provide a school building. Shingwauk knew that education was an inherent right for his people; he felt the same about resource rights. Throughout the 1840’s Chief Shingwauk was leading the push to have his people’s land and resource rights secured under treaty. After defending their territories from illegal miners at Mica Bay in November of 1849, Chief Shingwauk became one of the lead negotiators and signatories to the 1850 Robinson-Huron Treaties.

As a leader already successful in meeting a broad range of challenges with the newcomers, Shingwauk knew that he and his Band had to be steadfast in holding to the Vision but flexible in planning and implementing its realization as circumstances changed. The two centuries that followed demonstrate how understanding and determined he, his descendants and his followers have been.

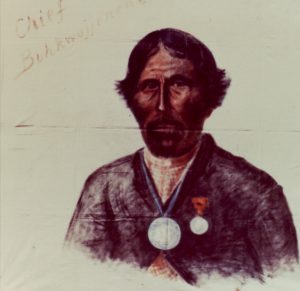

Augustine Shingwauk and Buhkwujjenene

In his Journal of 1871, Augustine Shingwauk tells how in the early 1830s his father Chief Shingwauk, after calling a council, led a delegation to York, Toronto to petition Lt. Governor John Colborne (1778-1863) and Bishop Charles Stewart (1775-1837) to support ongoing missionary work at Garden River. William McMurray, a missionary arrived in the fall of 1832 bringing with him some of the resources required to implement a Teaching Wigwam and to enable the Band’s development plans; McMurray remained until 1838 when government support began to falter. To Colborne and Stewart, and most of those who would succeed them, promulgation of Christianity among Indigenous Peoples was critical to ‘civilizing’ and thus integrating them into Canadian society. Augustine recounts,

‘We went in canoes as far as Penetanguishene, and then we landed and walked the rest of the way. The Great White Chief received us kindly, and we told him what we had come for. He replied to us in these words: ‘Your Great Father, King George, and all his great people in the far country across the sea, follow the English religion. I am a member of this Church. I think it right that the Chippeways, who love the English nation, and have fought under the English flag, should belong to the Church of England’.

They returned home, British flag in hand, with instructions from Colborne to raise it dutifully as a sign of their agreement. Cognizant of their obligations, both to the Crown and the Church, they returned satisfied that they would receive the requested support.

The Reverend James Chance (1829-1897) had arrived with his wife in 1855, a few months before the death of the old Chief Shingwaukonse. The Chances brought with them a renewed sense of optimism and motivation.

The now Chief Augustine Shingwauk and his brother Buhkwujjenene (1811-1900) were deeply committed to their father’s vision. They were driven toward ‘industrial education’ to better prepare the Anishinaabe to meet the challenges of increasing settler competition for resources and opportunities. Through the Wilsons’ visits with the Chances, the Shingwauk brothers had come to know them well. When James Chance left off to his new posting, Augustine quietly boarded the steamer that was returning them to Sarnia. Upon their arrival, he approached Reverend E.F. Wilson (1844-1915) with his plan to appeal to the Church of England at their upcoming meeting in Toronto. Wilson agreed to join Augustine in petitioning for their help in establishing a big Teaching Wigwam:

‘I told the Black-coats (missionaries) I hoped before I died I should see a big teaching wigwam built at Garden River, where children from the great Chippeway Lake would be received and clothed, and fed, and taught how to read and how to write, and also how to farm and build houses, and make clothing; so that by and by they might go back and teach their own people.’

Augustine’s appeal was successful and, continuing their journey of Southern Ontario, he and Wilson began the first of many Teaching Wigwam fundraising tours. Buhkwujjenene had traveled with the Wilson to England in 1872 on one tour and addressed many audiences about Shingwauk’s vision for a teaching wigwam. Even meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Prince of Wales, Buhkwujjenene was described as an eloquent speaker and a strong leader for his people. Augustine passed away in December 1890, having resisted with other chiefs the oppressive and restrictive policies of the Indian Act (1876). Buhkwujnenene succeeded Augustine as hereditary chief and carried on the struggle.

From the beginning, actualizing Shingwauk’s Vision involved collaboration based upon mutual respect and goals. As imperial and settler interests shifted to industrial resource extraction on a global scale, ‘Indian Policy’ changed and suspicion took hold, challenging the sensibilities of Indigenous Peoples and settlers alike. As early as the 1871 fundraising tour, Augustine reported his fear of looking like ‘a fool’ being asked ‘who I was, and what I had come for,’ including ‘what I thought of the recent Indian outbreaks in the country of the Long-knives.’

Indigenous Peoples found themselves in a precarious position; once sought-after war allies, guides, and partners in the fur-trade, were now, in the opinion of most policy-makers by this time, reduced to people of little value and consequence. Government goals shifted from integration to removal, and the era of residential schools was born.